Cluster Munition Monitor 2013

Contamination and Clearance

Summary

A total of 26 states and three other areas were believed to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants as of 1 July 2013. Twelve of these states have ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions[1], two have signed but not yet ratified[2], while another 12 have neither signed nor acceded.[3] Seven states—Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Vietnam—as well as one other area, Nagorno-Karabakh, have estimated contamination covering 10km² or more of land.

The Monitor has calculated that in 2012 at least 59,171 unexploded submunitions were destroyed during clearance of almost 78km² of land contaminated by cluster munitions in 11 states and two other areas. This data, however, is known to be incomplete due to the fact that reporting by states and operators on clearance of cluster munition remnants is partial and inconsistent in content, format, and quality.

Eight contaminated States Parties and signatories conducted clearance of unexploded submunitions in 2012: Afghanistan, BiH, Croatia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mauritania. Clearance of cluster munition remnants was also conducted in non-signatories Cambodia, Serbia, Vietnam, and Yemen, as well as two other areas, Nagorno-Karabakh and Western Sahara.

Global Contamination

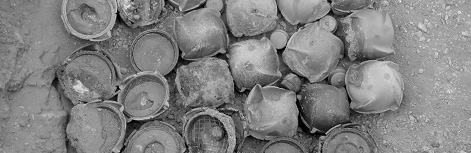

Cluster munition remnants are defined in the convention as covering four types of hazard; unexploded submunitions, unexploded bomblets, failed cluster munitions, and abandoned cluster munitions.[4] Unexploded submunitions pose the greatest threat to civilians, primarily as a result of their sensitive fuzing but also because of their appearance in terms of shape, color, and metal content, which often attracts tampering, playful attention, or collection, especially by boys and young men.

As detailed in the table below, a total of 26 states and three other areas are believed to have cluster munition remnants, including unexploded submunitions, on their territory as of 1 July 2013. Twelve of the states contaminated by cluster munition remnants are States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and have committed to clear their land within 10 years, while another two have signed but not yet ratified.

With reports in 2013 confirming cluster munitions contamination in Somalia and Yemen, there are two additions to the list of contaminated states since reporting in July 2012.[5]

Grenada declared it was free of cluster munition contamination at the Third Meeting of States Parties in September 2012, following technical survey and non-technical survey[6] in 2012 by clearance operator Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA).[7] Accordingly, Grenada has been removed from last year’s list of states contaminated with cluster munition remnants.

States and other areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants

|

Africa |

Americas |

Asia-Pacific |

Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia |

Middle East and North Africa |

|

Chad |

Chile |

Afghanistan |

BiH |

Iraq |

|

DRC |

|

Lao PDR |

Croatia |

Lebanon |

|

Mauritania |

|

Cambodia |

Germany |

Libya |

|

Somalia |

|

Vietnam |

Montenegro |

Syria |

|

South Sudan |

|

|

Norway |

Yemen |

|

Sudan |

|

|

Azerbaijan |

Western Sahara |

|

|

|

|

Georgia (South Ossetia) |

|

|

|

|

|

Russia (Chechnya) |

|

|

|

|

|

Serbia |

|

|

|

|

|

Tajikistan |

|

|

|

|

|

Kosovo |

|

|

|

|

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

|

|

6 states |

1 state |

4 states |

10 states and 2 areas |

5 states and 1 area |

Note: Convention on Cluster Munition States Parties and signatories are indicated in bold and other areas in italics.

Residual or suspected contamination

Another 13 states may also have a small amount of contamination, including Angola,[8] Colombia,[9]

Eritrea,[10] Ethiopia,[11] Iran,[12] Israel,[13] Jordan,[14] Kuwait,[15] Mozambique,[16]

Palau,[17] and Saudi Arabia.[18] Both Argentina and the United Kingdom (UK) claim sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Malvinas, which may contain areas with unexploded submunitions.[19]

Extent of contamination

The extent of contamination across affected states varies significantly. Seven states and one other area have the greatest contamination from cluster munition remnants (more than 10km²), particularly unexploded submunitions (see table below).

Extent of contamination in cluster munition-affected states and other areas[20]

(as of July 2013)

|

State/area |

Estimated extent of contamination (km2) |

No. of confirmed and suspected hazardous areas |

|

Lao PDR |

No credible estimate |

Not known |

|

Vietnam |

No credible estimate |

Not known |

|

Iraq |

No credible estimate |

Not known |

|

Cambodia |

489.23* |

990 |

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

88.40 |

241 |

|

Lebanon |

13.42 |

166 |

|

BiH |

12.18 |

669 |

|

Mauritania |

10 |

8 |

|

Serbia |

9.01 |

26 |

|

Afganistan |

7.64 |

22 |

|

Croatia |

4.47 |

7 |

|

Germany |

4 |

1 |

Note: Convention on Cluster Munition States Parties and signatories are indicated in bold and other areas in italics.

*This figure is likely to rise following additional survey.

States Parties

Twelve States Parties are contaminated by cluster munition remnants, with the heaviest contamination to be found in Lao PDR and Lebanon:

- Afghanistan is contaminated by cluster munition remnants primarily from Soviet use of air-dropped and rocket-delivered submunitions, and from United States (US) aircraft dispersing 1,228 cluster munitions containing an estimated 248,056 submunitions between October 2001 and early 2002.[21] Afghanistan reported 22 remaining cluster munition hazardous areas contaminated with BLU-97 submunitions[22] covering a total of 7.64km² in the assessment of all explosive remnants of war (ERW) contamination submitted for its Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline extension request in 2012.[23] Submunition contamination appears to be more widespread, however, with some demining operators reporting that they continue to find cluster bomb submunition remnants while on demining tasks.[24]

- BiH is contaminated with cluster munition remnants, primarily as a result of Yugoslav aircraft dropping BL-755 cluster bombs in the early stages of the 1992–1995 conflict related to the break-up of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. NATO forces also used them in Republika Srpska.[25] The first phase of a general survey completed by NPA in 2011 identified 140 areas hit by air strikes and artillery with an estimated total of 3,774 submunitions, and additional contamination around a former ammunition factory at Pretis that was hit by a NATO air strike. It identified 669 suspected hazardous area (SHA) polygons covering a total of 12.18km², of which 3.23km² is believed to be high risk. Some 5km² is contaminated by artillery-delivered submunitions: 3.9km² by BL-755 and 3.1km² by KB-1 submunition remnants.[26]

- Chad is contaminated by cluster munition remnants, but the precise extent remains to be determined. In December 2008, Chad stated it had “vast swathes of territory” contaminated with “mines and UXO [unexploded ordnance] (munitions and submunitions).”[27] Mines Advisory Group (MAG) found unexploded Soviet PTAB-1.5 submunitions close to Faya Largeau during a 2010–2011 re-survey of mine and ERW contamination.[28]

- Chile has identified four areas contaminated with cluster munition remnants located within three military training bases in three regions. The combined total area of the training bases is estimated at 969km². The precise extent of cluster munition-contaminated area will be determined during technical survey and clearance.[29]

- Croatia has areas contaminated by mainly KB-1 type cluster munition remnants left over from the conflict in the 1990s following the dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. By the end of 2012, these covered an area of 4.47km² across seven counties but most contamination (86%) is located in three counties, Zadarska (52%), Splitsko-dalmatinska (18%), and Ličko-senjska (16%).[30]

- Germany announced in June 2011 that it had identified areas suspected of containing cluster munition remnants at a former Soviet military training range at Wittstock in Brandenburg.[31] Germany has reported the size of the area as 4km²; the type and extent of cluster munitions remnants are unknown, but a historical and technical survey is ongoing with the results expected in 2013.[32]

- Iraq’s cluster munition contamination is believed to be large but the extent is not known with any degree of accuracy. In northern Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan), MAG has found, and in 2012 continued to clear, cluster munition remnants from strikes around Dohuk in 1991 launched by coalition forces.[33] Heavy contamination exists in central and southern Iraq as a result of extensive use of cluster munitions by allied troops during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, particularly around Basra, Nasiriyah, and the approaches to Baghdad. In 2004, Iraq’s National Mine Action Authority identified 2,200 sites of cluster munition contamination along the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys.[34] Submunitions made up a significant share of the items cleared by commercial companies working on clearance of southern oilfields and for Basra-based Danish Demining Group (DDG).[35]

- Lao PDR is the world’s most heavily cluster munition-contaminated country. The US dropped more than 270 million submunitions between 1964 and 1973.[36] There is no agreed estimate of the true extent of contamination from unexploded submunitions, but close to 70,000 cluster munition strikes have been identified, each with an average strike “footprint” of 125,000m² (0.125km²).[37] Lao PDR continues to state that cluster munitions contaminate approximately 8,470km² and overall contamination by UXO covers more than 84,000km² (around 35% of the Laotian territory).[38] Such estimates, however, are based on bomb targeting data that clearance operators have found bears little relation to actual contamination on the ground. After more than 15 years of UXO/mine action, Lao PDR has not yet conducted sufficient survey to produce a credible estimate of the total area contaminated in the country. The National Regulatory Authority (NRA) has reported 10 of Lao PDR’s 17 provinces are “severely contaminated” by explosive remnants of war, affecting up to a quarter of all villages.[39]

- Lebanon is affected by cluster munition contamination that originates primarily from the July–August 2006 conflict with Israel, but parts of the country remain affected from cluster munitions used in the 1980s. As of May 2013, 13.42km² was suspected to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants,[40] a decrease from 17.86km² a year earlier.[41]

- In Mauritania, survey in 2012 by NPA identified eight areas containing cluster munition remnants in the northeast part of the country near the border with Morocco (Western Sahara).[42] NPA estimated the total contaminated area at 10km². This represents a revised estimate of an additional 1km² and three confirmed hazardous areas (CHAs) since 2011.

- Montenegro informed States Parties in April 2012 that it was contaminated by cluster munition remnants left over from conflict in the 1990s. Non-technical survey conducted by NPA between December 2012 and April 2013 identified 87 polygons of SHAs or CHAs covering a total area of 1.72km² affecting five communities in three municipalities. The most affected area was Golubovci municipality, particularly around its airport, accounting for 1.38km² of the total, followed by Tuzi and Rožaje municipalities. There are signs that submunitions may also be present in two other areas of Plav municipality, Bogajice and Murino, which could not be immediately investigated because of high levels of snow.[43]

- Norway reported in its initial Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 report that the Hjerkinn “shooting range”[44] in central Norway contains an estimated 30 unexploded DM 1383/DM 1385 submunitions over an area of 617,300m2 as a result of test firing.[45] Norway has reported that clearance of the area, under the responsibility of the Ministry of Defense, remains ongoing[46] and has projected clearance to be completed “no later than 2013.”[47]

Signatories

Two signatories are believed to be contaminated with cluster munition remnants: DRC and Somalia.

In DRC, the scale of contamination from unexploded submunitions has not yet been quantified. However, cluster munition remnants have been found in the provinces of Équateur, Katanga, Maniema, and Oriental;[48] in 2011, the DRC reported 32 cluster submunition locations in five provinces.[49] The ongoing national survey to be completed in December 2013 includes questions regarding the existence and location of submunitions.[50]

Somalia’s level of cluster munition contamination is unknown. Dozens of dud PTAB-2.5M and some AO-1SCh explosive submunitions have been found within a 30km radius of the Somali border town of Dolow. The contamination is believed to have occurred during the 1977–1978 Ogaden War.[51] On 2 January 2013, The Development Initiative (TDI) removed a PTAB-2.5M submunition in Bundundu village, located in the Dolow district.[52]

Non-signatories

Several of the 12 contaminated states that have not joined the convention have active clearance programs in place, including Cambodia, Libya, Serbia, South Sudan, and Vietnam.

- Cambodia, particularly its eastern and northeastern areas bordering Lao PDR and Vietnam, is affected by between 1.9 million and 5.8 million cluster munition remnants as a result of US aircraft dropping approximately 26 million explosive submunitions in Cambodia during the Vietnam War.[53] In February 2011, Thailand’s use of cluster munitions in Cambodia’s northern province, Preah Vihear, resulted in additional submunition contamination over an area of approximately 1.5km².[54] Cluster munition remnants in Cambodia include unexploded BLU-24, BLU-26, BLU-36, BLU-42, BLU-43, BLU-49, BLU-61, M42, M46, and M85 submunitions.[55] As of April 2013, an ongoing baseline survey (BLS) identified 990 suspected cluster munition-contaminated areas covering an area of 489.23km², particularly in southeastern Kratie province bordering Vietnam, northeastern Stung Treng province and northern Preah Vihear province. This figure is likely to rise as a result of survey of additional areas.[56]

- Libya was added to the list of contaminated states following use of cluster munitions by government forces in April 2011. Operators identified three types of cluster munition, including Chinese, Russian, and Spanish devices,[57] but no comprehensive survey has been possible and the precise extent of contamination from cluster munition remnants is not known.

- Serbia’s problem with cluster munition remnants dates from NATO air strikes in 1999, which hit 16 municipalities across the country.[58] Serbia reported that, as of March 2013, it had 13 confirmed cluster munition hazards affecting 2.36km² and another 13 suspected hazards covering 6.65km².[59] NPA surveyed cluster munition contamination starting in 2007 and by the end of 2012 had estimated the overall problem at about 7km².[60]

- South Sudan has identified 629 sites containing cluster munition remnants in all 10 states. The UN Mine Action Coordination Centre reported that in April 2013 there were 58 known dangerous areas containing unexploded submunitions in seven states: Central Equatoria, East Equatoria, West Equatoria, Upper Nile, West Bahr El Ghazal, Jonglei, and Unity.[61]

- Sudan is believed to have nine areas contaminated with unexploded submunitions, while another 81 have been released.[62] The Mine Action Center has not reported on cluster munition contamination since 2011. In May 2012, a cluster bomb was discovered in the village of Angolo in the Nuba Mountains in South Kordofan.[63] The government of Sudan has denied using cluster munitions in South Kordofan.[64]

- Syria is contaminated with cluster munition remnants due to the ongoing armed conflict. While the full extent of contamination is unknown, as of April 2013 a number of locations in Syria have been identified as areas where cluster munitions have been used, including: Abu Kamal,[65] near Azaz,[66] Deir Jamal, Talbiseh al-Za‘faraneh, Abil, Binnish, Deir al-Asafeer, Douma, and the governorates of Aleppo, Idlib, Deir al-Zor and Latakia.[67]

- Vietnam is one of the most cluster munition-contaminated countries in the world as a result of an estimated 413,130 tons of submunitions used by the US in 1965–1973.[68] Cluster munitions were used in 55 provinces and cities, including Haiphong, Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, Hue, and Vinh, but no accurate assessment exists of the extent of cluster munition contamination. Substantial amounts of cluster munitions were abandoned by the US military, notably at or around old US air bases, including eight underground bunkers found in 2009, one of them covering an area of 4,000m² (0.004 km²) and containing approximately 25 tons of munitions.[69]

- Yemen is affected by cluster munition remnants, but the extent is not known. The Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC) has confirmed the presence, but not the origin, of cluster munitions remnants in four districts on the border between Sa’ada governorate and Saudi Arabia[70] consisting mainly of type BLU-97, dual-purpose improved conventional munitions (DPICM), and BLU-61.[71] Amnesty International reported the presence of unexploded BLU-97 submunitions in June 2010, which it alleged originated from a US cruise missile attack on 17 December 2009 on the community of al-Ma’jalah in the Abyan area in south Yemen[72], but YEMAC has not been able to access the area to confirm the presence of submunitions.[73] By the end of 2012, YEMAC reported it had found and destroyed a total of 440 cluster munition remnants but did not identify the types or origin of these munitions.[74]

Other areas

- Kosovo is affected by remnants of cluster munitions used by the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia armed forces in 1998−1999 and by a NATO campaign in 1999, during which aircraft dropped 1,392 bombs containing 295,700 submunitions.[75] Following demining operations between June 1999 and December 2001, the UN reported that “the problems associated with landmines, cluster munitions and other items of unexploded ordnance in Kosovo have been virtually eliminated.”[76] Subsequent investigation, however, revealed considerably more contamination.[77] By the end of 2012, Kosovo reported 42 confirmed and four suspected cluster munition hazards.[78] HALO Trust and Kosovo Mine Action Center started resurvey of all Kosovo in 2013 and expected to complete work in the same year.[79]

- Nagorno-Karabakh has a significant problem of cluster munition remnants, particularly in the Askeran, Martuni, and Martakert regions, where more than 75% of the remaining cluster munition problem is located. Large quantities of cluster munitions were dropped from the air during the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict over a six-year period. As of December 2012, HALO estimated the remaining area in need of battle area clearance (BAC) was 88.4km² resulting from 241 cluster munition strikes.[80] This is an increase from an estimated area of 70.9km² as of July 2012, despite clearance of 7.6km² resulting in the destruction of 169 submunitions.[81]

- Western Sahara has a problem with cluster munition remnants where a total of 23 cluster munition strike sites remained to be cleared across an estimated area of 3.88km².[82] Previously unknown contaminated areas have continued to be identified as recently as June 2012.[83] A survey managed by Landmine Action which was completed at the end of 2008 determined that, among the range of explosive ordnance contaminating Western Sahara, unexploded submunitions posed the greatest threat to people and animals.[84] Western Sahara was expected to be cleared of known cluster munition remnants outside the buffer zone with the Moroccan berm (sand wall) by the end of 2012. However, the discovery of previously unknown contaminated areas has meant that this deadline has not been able to be met.

Clearance of Cluster Munition Remnants

Reporting by states and operators on clearance of cluster munition remnants is incomplete and inconsistent in content, format, and quality. Based on available reporting and information gathered directly from programs, in 2012 at least 59,171 unexploded submunitions were destroyed during clearance operations of nearly 78km² of land contaminated with cluster munitions in 11 states and two other areas, as detailed in the table below. The bulk of the clearance in 2012 was reported in Lao PDR and may include a significant quantity of BAC not directly concerned with destruction of cluster munition remnants.

In 2011, the Monitor reported that at least 52,845 unexploded submunitions were destroyed during clearance operations of some 55km² of land contaminated by cluster munitions in 11 states and two other areas.[85] The data available suggests an increase in clearance of cluster munition-contaminated land in 2012, but states’ reporting varies widely in quality and does not consistently disaggregate clearance of cluster munitions from battle area clearance of other ERW. Most of the increase recorded can be accounted for by higher overall clearance reported by Lao PDR and the clearance recorded in 2012 by BiH.

Clearance of cluster munition remnants in 2012

|

State/area |

Area cleared (km2) |

No. of submunitions destroyed |

|

Afghanistan* |

0 |

Not reported |

|

BiH |

2.01 |

343 |

|

Chad |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Chile |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Croatia |

0.77 |

277 |

|

DRC |

Not reported |

55 |

|

Germany** |

0 |

0 |

|

Iraq*** |

Not available |

1,512 |

|

Lao PDR |

54.42 |

46,218 |

|

Lebanon |

2.98 |

4,362 |

|

Mauritania |

0.35 |

28 |

|

Norway**** |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Cambodia |

5.45 |

1,230 |

|

Libya |

No data |

No data |

|

Serbia |

1.43 |

661 |

|

South Sudan |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Sudan |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Vietnam***** |

Not reported |

3,556 |

|

Yemen |

Not reported |

440 |

|

Kosovo |

Not reported |

Not reported |

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

7.6 |

169 |

|

Western Sahara |

2.97 |

320 |

|

Total |

77,98 |

59,171 |

Note: States Parties and signatories are indicated in bold, other areas in italics. * International mine clearance operators destroyed cluster submunitions that are not reflected by government recording methods.** Clearance will not begin until survey is complete in 2013. *** Data incomplete. **** Norway has announced that clearance will be complete by the second half of 2013. ***** The Army’s Engineering Command reports the release of about 450km² but gives no data on numbers of submunitions cleared; NGOs report 3.48km² and 3,556 items cleared.

Clearance obligations

Article 4 clearance deadlines for States Parties

|

State Party |

Clearance deadline |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2022 |

|

BiH |

1 March 2021 |

|

Chad |

1 September 2023 |

|

Chile |

1 June 2021 |

|

Croatia |

1 August 2020 |

|

Germany |

1 August 2020 |

|

Iraq |

1 November 2023 |

|

Lao PDR |

1 August 2020 |

|

Lebanon |

1 May 2021 |

|

Mauritania |

1 August 2022 |

|

Montenegro |

1 August 2020 |

|

Norway |

1 August 2020 |

|

Norway |

1 August 2020 |

Under the Convention on Cluster Munitions, each State Party is obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under its jurisdiction or control as soon as possible but not later than 10 years after the entry into force of the convention for each State Party. If unable to complete clearance in time, a state may request an extension of the deadline for periods of up to five years. Clearance deadlines for contaminated States Parties are shown below.

In seeking to fulfill their clearance and destruction obligations, affected States Parties are required to:

- survey, assess, and record the threat, making every effort to identify all contaminated areas under their jurisdiction or control;

- assess and prioritize needs for marking, protection of civilians, clearance, and destruction;

- take “all feasible steps” to perimeter-mark, monitor, and fence affected areas;

- conduct risk reduction education to ensure awareness among civilians living in or around areas contaminated by cluster munitions;

- take steps to mobilize the necessary resources (at national and international levels); and

- develop a national plan, building upon existing structures, experiences, and methodologies.[86]

Norway, as President of the Third Meeting of States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, presented a draft working paper on “Compliance with Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions” in April 2013 designed to clarify what constitutes compliance with Article 4 of the convention.[87] The paper’s stated aim is to unpack the key obligations that states must fulfill in order to be able to make a declaration of compliance. The paper is due to be considered for adoption at the Fourth Meeting of States Parties to the convention in September 2013.

Land release

A set of guiding principles for land release of cluster munition-contaminated areas published by the Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC) in June 2011,[88] calls for affected states to put sufficient resources into properly identifying cluster munition-affected areas before carrying out clearance. It recommends states conduct a desk assessment (of ground conditions, weapons delivery systems, battlefield data, etc.) followed by non-technical survey to collect field evidence of contamination and, where required, technical survey to define a cluster strike footprint. It notes clearing cluster munitions should not be approached in the same way as clearing landmines and suggests states apply principles laid out in the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) 09.11 (Battle Area Clearance) for land only contaminated with cluster munition remnants.

To promote more efficient release of land, amendments to IMAS adopted in April 2013 remove General Assessment (formerly 08.10) and set out to simplify and clarify standards on Land Release (now 07.11), Non-Technical Survey (now 08.10) and Technical Survey (now 08.20). They seek to make clear distinctions between suspected hazardous areas and confirmed hazardous areas and provide more guidance on use of evidence to avoid inflating estimates of contamination where evidence does not justify it. They also seek to clarify basic principles of technical survey, the distinctions between area reduction and clearance, and the requirement to apply “all reasonable effort” in use of evidence to plan and interpret the results of technical survey.

In a bid to increase productivity, international operators in the meantime have focused increasingly on evidence-based battle area clearance for tackling cluster munitions and on developing survey methodology better tailored to the particular challenges of this type of contamination. A cluster munition remnants survey approach developed by NPA in Lao PDR, and endorsed or adapted by a number of other operators, begins with desk assessment and non-technical survey in order to define start points for technical survey. Clearance only takes place once a confirmed hazardous area is established and reported to the National Regulatory Authority. Sub-surface clearance is conducted as necessary according to the evidence, and a mixture of surface and sub-surface clearance may be considered sufficient clearance for an entire area to be released. A “fadeout” principle determines the distance to which clearance continues after finding what is perceived as the last target item in a footprint.[89]

Clearance by States Parties

- Afghanistan did not report any cluster munitions clearance in 2012.[90] That result, however, reflects the fact that operators did not tackle any of the 22 hazards recorded in the Mine Action Coordination Center for Afghanistan (MACCA) database as cluster munition-contaminated sites. HALO and RONCO Consulting Corporation, an international demining operator, reported in 2012 that its operators had found an old cache of 200 barrels of cluster munitions buried at Kabul International Airport.[91] MACCA’s implementing partners cleared submunitions on other tasks but these were reported as UXO.[92]

- In BiH, NPA, the only operator accredited for clearance of cluster munitions, commenced technical survey and clearance in 2012, releasing a total of 2.01km², of which the majority (1.27km²) was cancelled by non-technical survey, a further 0.58km² released through technical survey and only applying full clearance to 0.16km².[93] Survey in 2011 by NPA had identified 669 SHA polygons covering a total of 12.18km², of which 3.23km² is believed to be high risk.[94] Clearance in 2012 released nine areas and destroyed 343 submunitions.

- Chad has not reported the clearance of any submunitions since 2011.

- Chile has not yet reported the clearance of any cluster munition remnants.

- Croatia cleared 767,142m² (0.77km²) in 2012, one-third more area than the previous year, releasing 15 hazardous areas and destroying 277 submunitions, all of them type KB-1. In the process, it said it had completely cleared Dubrovnik-Neretva county of cluster munition remnants, as well as an area around the town of Nin and “Krka” national park.[95]

- Germany has not yet reported the clearance of any cluster munition remnants.

- Iraq’s clearance is not comprehensively reported or recorded. In Kurdish northern Iraq, MAG—the only operator identified as clearing cluster munitions—reported destroying 779 submunitions in 2012.[96] In central and southern Iraq, DDG focused on cluster munitions tasks clearing 658 submunitions with a further 75 cleared by Iraqi Mine Clearance Organization (IMCO),[97] but clearance by commercial operators on behalf of the oil industry, believed to be substantial, was not recorded.

- In Lao PDR, operators cleared a total of 54.42km² in 2012, 40% more than the previous year, destroying a total of 46,218 unexploded submunitions through BAC (29,662 submunitions), technical survey (2,392 submunitions), and roving clearance tasks (14,164 submunitions). Humanitarian operators only marginally increased the amount of land they cleared but destroyed 36% more submunitions in 2012 than the previous year.[98]

- In Lebanon, a total of 2.98km² of contaminated land was cleared in 2012 by international and national NGOs, resulting in the destruction of 4,362 unexploded submunitions,[99] a small increase compared to clearance of 2.51km² in 2011 that resulted in the destruction of 4,888 submunitions. Lebanon has 13.42km² of hazardous areas remaining as of May 2013, down from approximately 55km² in 2006.[100] Under its strategic plan for 2011–2020, the Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) plans to complete clearance of cluster munition remnants by 2016.[101] Targets contained in the plan are dependent on specific clearance capacity and fell short in 2012,[102] mainly as a result of dwindling funds. The Swiss Demining Foundation closed its operations due to a lack of funding in March 2013.[103] If Lebanon is to reach its target of clearing all cluster munition remnants by 2016[104], its success will depend on maintaining 30 BAC teams in 2012–2016, for which it needs sustained international funding. If not, the 2016 target may be missed.[105]

- Mauritania commenced clearance operations in April 2013 and completed clearance of 350,000m² (0.35km²) resulting in the destruction of 28 cluster submunitions through a collaboration between NPA and the National Authority for Mine Action in Mauritania.[106]

- Montenegro did not conduct clearance of cluster munition-contaminated areas in 2012, although the Regional Centre for Divers’ Training and Underwater Demining (RCUD) reported that in July 2012 it found and destroyed two unexploded submunitions in the course of underwater clearance of three tons of UXO in the river Zeta in Podgorica.[107] In 2013, NPA expected to release 1.2−1.3km² through technical survey and clearance, and 0.4−0.5km² through non-technical survey.[108]

- Norway reported in April 2013 that clearance of the Hjerkinn firing range was ongoing.[109] It said the Ministry of Defense estimates that clearance will be completed no later than 2013.[110]

Clearance by signatories

- In DRC, the UN Mine Action Coordination Centre (UNMACC) reported 55 submunitions were found during clearance operations in Équateur province in 2012.[111] In the first months of 2013, an additional nine submunitions were found in Maniema province.[112] The scale of residual contamination from unexploded submunitions has not yet been quantified. The ongoing national survey to be completed in December 2013 includes questions regarding the existence and location of submunitions.[113]

Clearance by non-signatories

- In Cambodia, the Cambodia Mine Action Centre (CMAC), the biggest of the humanitarian demining operators, recorded clearing 38 cluster munition hazards covering 5.45km² and destroying 549 submunitions, in addition to clearing a further 681 cluster munition remnants in the course of BAC tasks conducted in eastern Cambodia in 2012.[114]

- Serbia released 20 suspected areas of cluster munition contamination covering 2.13km² through survey in 2012 and cleared another eight areas covering 1.43km²— almost 25% more clearance than in 2011—while destroying 661 submunitions. Ninety-nine percent of submunitions destroyed were in Kuršumlija municipality. NPA estimated that by the end of 2013, Serbia’s remaining submunition contamination would cover about 6.1km².[115]

- In Sudan, the UN Mine Action Office does not distinguish between clearance of different types of ERW in its reporting and can neither confirm how much land was cleared of cluster munition remnants in 2011 and 2012 nor how many submunitions were destroyed.

- Vietnam’s army is responsible for most ERW clearance and reported clearing a total of about 450km² in 2012 but gave no details of cluster munitions cleared nationally.[116] In Ha Tinh province alone, military teams reportedly destroyed 600 submunitions between April and August 2012 along with other UXO.[117] Four international NGOs operating in four central provinces cleared an additional 3.48km² in 2012, marginally less area than in 2011, and reported the destruction of 3,556 unexploded submunitions through BAC.[118]

[1] Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Chile, Croatia, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, Montenegro, and Norway.

[2] Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Somalia.

[3] Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Georgia, Libya, Russia, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Vietnam, and Yemen.

[4] Unexploded submunitions are submunitions that have been dispersed and have landed but have failed to explode as intended. Unexploded bomblets are similar to unexploded submunitions but refer to “explosive bomblets” which have been dropped from an aircraft dispenser but have failed to explode as intended. Failed cluster munitions are cluster munitions that have been dropped or fired but the dispenser has failed to disperse the submunitions as intended. Abandoned cluster munitions are unused cluster munitions that have been left behind or dumped and are no longer under the control of the party that left them behind or dumped them. See Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 2, paragraphs 4, 5, 6, 7, and 15.

[5] Yemen was previously listed by the Monitor as having a “suspected” cluster munition remnants contamination problem. For both Somalia and Yemen, cluster munition use occurred prior to 2012.

[6] The International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) define non-technical and technical survey as follows: ‘“Non-technical Survey’ refers to the collection and analysis of data, without the use of technical interventions, about the presence, type, distribution and surrounding environment of mine/ERW contamination, in order to define better where mine/ERW contamination is present, and where it is not, and to support land release prioritisation and decision-making processes through the provision of evidence... ‘Technical Survey’ refers to the collection and analysis of data, using appropriate technical interventions, about the presence, type, distribution and surrounding environment of mine/ERW contamination, in order to define better where mine/ERW contamination is present, and where it is not, and to support land release prioritisation and decision making processes through the provision of evidence.” IMAS 07.11 on Land Release, First Edition, 10 June 2009, pp. 3–4.

[7] Statement of Grenada, Convention on Cluster Munitions Third Meeting of States Parties, Oslo, 11 September 2012.

[8] While there is no confirmed contamination from cluster munition remnants in Angola, there may be a small residual threat from either abandoned cluster munitions or unexploded submunitions. However, clearance operators have not reported finding any cluster munition remnants since 2008.

[9] In December 2010, the Colombian Air Force stated that cluster munitions were last used in Colombia in October 2006. Presentation on Cluster Munitions by the National Ministry of Defense of Colombia, Bogotá, 9 December 2010.

[10] It is not known to what extent Eritrea has cluster munition remnants on its territory as a result of the 1998–2000 conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea in which both used cluster munitions. Eritrean forces were also heavily bombed in 1988–1990 during the struggle for independence, including with cluster munitions. The Ethiopia and Eritrea Mine Action Coordination Center (UNMEE MACC) reported that in 2007, BL-755 and (an unidentified variant of) PTAB-2.5 unexploded submunitions were found in Eritrea. UNMEE MACC, “Annual Report 2008,” undated draft, p. 1, provided by email from Anthony Blythen, Programme Officer, UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS), 7 April 2009.

[11] In 2004, the Eritrea-Ethiopia Claims Commission concluded that Eritrea had conducted four cluster munition strikes on 5 June 1998 in the vicinity of a school in Ayder and at the airport surrounding a neighborhood in Mekele town, both in Tigray region. In June 2012, the Permanent Mission of Ethiopia to the UN in Geneva informed the Monitor that cluster munition remnants “are still found in the area” around an elementary school in Ayder. Letter from the Permanent Mission of Ethiopia to the UN in Geneva, 13 June 2012.

[12] The precise nature and extent of Iran’s contamination by explosive remnants of war (ERW) is not known, although the contamination is suspected to be significant and to contain cluster munition remnants.

[13] According to the commander of the National Police’s bomb squad, all known strike locations of cluster munitions fired into Israel from Lebanon in 2006 were cleared of any remnants found at the time. However, no systematic survey was conducted, nor was there any attempt to identify strikes that may have landed in the desert. In addition, based on an interview with the head of Arava’s drainage authority, Survivor Corps has claimed that the Ktura Valley in Arava region is contaminated by unexploded submunitions. Survivor Corps, “Explosive Litter: Status Report on Minefields in Israel and the Palestinian Authority,” Report, June 2010, p. iv.

[14] Jordan may be affected by unexploded submunitions resulting from the use of cluster munitions on training ranges.

[15] Unexploded submunitions from the 1990–1991 Gulf War have been found in Kuwait, including six unexploded submunitions in Abdaly near the border with Iraq in May 2011 (believed to have been remnants of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990) that were subsequently destroyed by the Ministry of the Interior. In December 2010, 3.5 tons of unexploded ordnance, including an unspecified number of unexploded submunitions, were found south of Kuwait city. The area was cleared by Ministry of Defense personnel. Report in Al Qabas (daily newspaper), 12 May 2011, p. 10; and email from Dr. Raafat Misak, Scientific Researcher, Environment and Urban Development Division, Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research, 2 August 2011.

[16] In its initial Article 7 report, Mozambique stated that an unknown number of CBU-470 alpha bomblets were found in Changara District, Tête Province in July–August 2011 and April 2012. Mozambique will conduct a survey to determine the scope of any residual threat, although it believes that “the use of these weapons was limited and that clearance of unexploded submunitions can be managed within the scope of the existing mine action programme.” Mozambique, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for the period 1 September 2011 to 31 May 2012), Form F, 9 July 2012. In 2010, the NGO APOPO reported finding one dispenser containing 150 submunitions in Gaza province. Response to Monitor questionnaire by Andrew Sully, Programme Manager, APOPO, 3 May 2011.

[17] Cleared Ground Demining (CGD), which has been clearing ordnance in Palau since 2009, found a cluster munition remnant in 2010 and a further two unexploded submunitions were found in 2011. CGD, “Republic of Palau – 2010 Landmine Monitor Clearance Statistics,” undated but 2011; and email from Cassandra McKeown, Finance Director, CGD, 18 July 2011. See also NPA, “Assessment Mission (PALAU) Report,” October 2012, p. 4.

[18] Saudi Arabia may have a small residual problem of unexploded ordnance from the 1991 Gulf War, including cluster munition remnants. In 1991, Saudi Arabian and United States (US) forces used artillery-delivered and air-dropped cluster munitions against Iraqi forces during the Battle of Khafji. See Human Rights Watch (HRW), “Timeline of Cluster Munition Use,” Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC), 2009, www.stopclustermunitions.org.

[19] In November 2010, the UK stated that “there is only a very small residual risk that may exist from cluster munitions” and that it had “suitable measures in place to mitigate this.” Statement by Amb. Stephen Lillie, Head of Delegation, Convention on Cluster Munitions First Meeting of States Parties, Vientiane, 9 November 2010. The UK found and destroyed two submunitions during clearance operations in 2009–2010.

[20] While Lao PDR, Iraq, and Vietnam have been unable to quantify the extent of their cluster munition remnants contamination, Lao PDR—known to have the greatest extent of contamination of all states—and Vietnam are often described as having “massive” contamination, and Iraq as “very large.”

[21] Human Rights Watch and Landmine Action, Banning Cluster Munitions: Government Policy and Practice (Ottawa: Mines Action Canada, May 2009), p. 27.

[22] Statement of Afghanistan, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 15 April 2013.

[23] Afghanistan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, undated but submitted on 29 March 2012, p. 165.

[24] Interviews with Mine Action Coordination Centre of Afghanistan (MACCA) implementing partners, Kabul, 15–22 May 2013.

[25] NPA, “Implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM) in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” Sarajevo, undated but 2010, provided by email from Darvin Lisica, Programme Manager, NPA, 3 June 2010.

[26] BiH, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Initial Report, Form F, 20 August 2011, pp. 20–21.

[27] Statement of Chad, Convention on Cluster Munitions Signing Conference, Oslo, 3 December 2008.

[28] Email from Liebeschitz Rodolphe, Chief Technical Advisor, UNDP, 21 February 2011; and email from Bruno Bouchardy, Program Manager, MAG Chad, 11 March 2011.

[29] Chile, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form F, September 2012.

[30] Croatia, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form F, 2 May 2013.

[31] Statement of Germany, Mine Ban Treaty Standing Committee on Mine Clearance, Geneva, 21 June 2011.

[32] Germany, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 15 April 2013.

[33] Email from Zana Kaka, Acting Program Officer, MAG, 13 March 2013; and Zana Kaka, “IRAQ: Saving lives of returnees in Dohuk,” MAG, 28 May 2010.

[34] Landmine Action, “Explosive remnants of war and mines other than anti-personnel mines,” London, March 2005, p. 86.

[35] Email from Bazz Jolly, Operations/Program Manager, DDG Iraq, 15 July 2013; emails from Simon Porter, ERW Programme Manager, Majnoon Field Development, Shell EP International Ltd, 25 and 31 July 2012.

[36] “US bombing records in Laos, 1964–73, Congressional Record,” 14 May 1975.

[37] National Regulatory Authority (NRA), “National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action in Lao PDR,” www.nra.gov.la.

[38] Statement of Lao PDR, Convention on Cluster Munitions Third Meeting of States Parties, Oslo, 13 September 2012; and Lao PDR, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form F, 28 March 2013.

[39] NRA, “National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action in Lao PDR,” www.nra.gov.la.

[40] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Col. Hassan Fakih, Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC), 24 May 2013.

[41] Presentation by Maj. Pierre Bou Maroun, Director of Regional Mine Action Center, Nabatiye, 3 May 2012.

[42] Mauritania, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form F, 20 March 2013.

[43] NPA, “Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro,” July 2013, pp. 6 and 21.

[44] The area was used in 1986–2007 as a firing range.

[45] Norway, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form F, 29 April 2011.

[46] Statement of Norway, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, 17 April 2013.

[47] Statement of Norway, Convention on Cluster Munitions Third Meeting of States Parties, Oslo, 13 September 2012; and statement of Norway, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 17 April 2013.

[48] Email from Charles Frisby, former UN advisor, UN Mine Action Coordination Centre in DRC (UNMACC), 30 March 2011.

[49] DRC, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, 10 April 2012.

[50] Interview with Pascal Simon, Programme Manager, UNMACC, in Geneva, 17 April 2013.

[51] Email from Mohammed A. Ahmed, Director, Somalia Mine Action Authority, 17 April 2013.

[52] TDI, “Making progress in South Central Somalia as operations expand to new provinces,” January 2013. UNMAS Somalia, 2 January 2013, www.flickr.com/photos/unmassomalia/8385215689/.

[53] South East Asia Air Sortie Database, cited in Dave McCracken, “National Explosive Remnants of War Study, Cambodia,” NPA in collaboration with the Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA), Phnom Penh, March 2006, p. 15; HRW, “Cluster Munitions in the Asia-Pacific Region,” October 2008, www.hrw.org/news/2008/10/17/cluster-munitions-asia-pacific-region; and Handicap International (HI), Fatal Footprint: The Global Human Impact of Cluster Munitions (HI: Brussels, November 2006), p. 11.

[54] An assessment by the Cambodian Mine Action Centre and NPA immediately after the shelling identified 12 strike sites and contamination by unexploded submunitions over an area of approximately 1.5km². See Aina Ostreng, “Norwegian People’s Aid clears cluster bombs after clash in Cambodia,” NPA, 19 May 2011. NPA said evidence in the area suggested about one in five of the submunitions had failed to detonate. Thomas Miller, “Banks tied to cluster bombs named,” Phnom Penh Post, 26 May 2011.

[55] South East Asia Air Sortie Database, cited in Dave McCracken, “National Explosive Remnants of War Study, Cambodia,” NPA in collaboration with CMAA, Phnom Penh, March 2006, p. 15; HRW, “Cluster Munitions in the Asia-Pacific Region,” October 2008, www.hrw.org; Aina Ostreng, “Norwegian People’s Aid clears cluster bombs after clash in Cambodia,” NPA, 19 May 2011; and HI, Fatal Footprint: The Global Human Impact of Cluster Munitions (HI: Brussels, November 2006), November 2006, p. 11.

[56] “BLS Statistics by Land Classification,” data received by email from Eang Kamrang, Database Manager, CMAA, Phnom Penh, 11 April 2013.

[57] Email from Nina Seecharan, Desk Officer for Iraq, Lebanon and Libya, MAG, 5 March 2012.

[58] Statement of Serbia, Mine Ban Treaty Standing Committee on Mine Clearance, Geneva, 21 June 2011; and interview with Petar Mihajlović, Director, and Slađana Košutić, International Cooperation Advisor, Serbian Mine Action Centre (SMAC), Belgrade, 25 March 2011.

[59] Serbia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 26 March 2013, p. 21.

[60] Email from Vanja Sikirica, Programme Manager, NPA, Belgrade, 9 July 2013.

[61] Response to Monitor questionnaire from Robert Thompson, Chief of Operations, UN Mine Action Service, South Sudan, 24 May 2013.

[62] Based on a review by the CMC of cluster munition sites in the UN Mine Action Office database.

[63] Aris Roussinos, “In a Sudanese field, cluster bomb evidence proves just how deadly this war has become,” Independent, 24 May 2012; and “Cluster Bomb-Sudan,” Journeyman TV, May 2012.

[64] “Sudan denies use of cluster bombs,” United Press International, 28 May 2012.

[65] Brown Moses blog, 4 June 2013, www.brown-moses.blogspot.com/2013/06/the-cluster-munitions-of-syrian-civil.html.

[66] Some weapons experts have disagreed on whether the identified remnants found in Azaz are in fact cluster munition remnants. See Scott Bobb, “VOA Finds Evidence of Syrian Cluster Bomb Use,” Voice of America, 4 March 2013, www.voanews.com/content/voa_finds_evidence_of_syrian_cluster_bombs/1614779.html.

[67] HRW, “Syria: Mounting Casualties from Cluster Munitions,” 16 March 2013 and HRW, “Death from the Skies,” 10 April 2013.

[68] Vietnam’s Military Engineering Command has recorded finding 15 types of US-made submunitions. “Vietnam mine/ERW (including cluster munitions) contamination, impacts and clearance requirements,” Presentation by Sr. Col. Phan Duc Tuan, People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), in Geneva, 30 June 2011.

[69] Interview with Sr. Col. Phan Duc Tuan, PAVN, in Geneva, 30 June 2011.

[70] Interview with Abdul Raqeeb Fare, Deputy Director, YEMAC, Sanaa, 7 March 2013.

[71] Email from John Dingley, Chief Technical Advisor, YEMAC, 9 July 2013.

[72] Amnesty International, “Images of missile and cluster munitions point to US role in fatal attack in Yemen,” 7 June 2010, www.amnesty.org/en/news-and-updates/yemen-images-missile-and-cluster-munitions-point-us-role-fatal-attack-2010-06-04.

[73] Information from YEMAC forwarded by email from Rosemary Willey-Al’Sanah, UNDP, 27 April 2013.

[74] Ibid.

[75] “Kosovo, Humanitarian Mine Clearance,” HALO Trust brochure, undated but 2013.

[76] “UNMIK Mine Action Programme Annual Report – 2001,” Mine Action Coordination Cell, Pristina, undated but 2002, p. 1.

[77] HALO, “Failing the Kosovars: The Hidden Impact and Threat from ERW,” 15 December 2006, p. 1.

[78] Goran Gačnik, “ITF, Enhancing Human Security,” undated but 2013.

[79] Email from and telephone interview with Andrew Moore, Balkans Desk Officer, HALO, 16 July 2013.

[80] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Andrew Moore, HALO, 15 April 2013.

[81] Ibid.; and email from Andrew Moore, HALO, 9 March 2011.

[82] Emails from Ruth Simpson, Action on Armed Violence, 17 July 2013.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Email from Melissa Fuerth, Operations Officer, Landmine Action, 20 February 2009.

[85] Afghanistan, BiH, Cambodia, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Serbia, Thailand, UK, and Vietnam. The two other areas were Nagorno-Karabakh and Western Sahara. See CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2012 (Geneva: ICBL-CMC, September 2012), p. 47, www.the-monitor.org/cmm/2012/pdf/Cluster_Munition_Monitor_2012.pdf.

[86] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 4, paragraph 2.

[87] Norway, “Compliance with Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions,” April 2013, www.clusterconvention.org/files/2013/01/CCM-Art-4-draft-WP-April-2013-for-webdistribution.pdf.

[88] “CMC Guiding Principles for Implementing Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions,” June 2011.

[89] NPA, “NPA’s Operational Methods of Releasing Land: Cluster Munition Remnants,” undated but 2011.

[90] Email from MACCA, 11 March 2013.

[91] Interview with Chris North, Country Manager, and Ricky Nilson, RONCO Consulting Corporation, Kabul, 12 May 2012; “HALO Weapons and Ammunition Disposal Task: Kabul International Airport 02−05 December 2012,” received by email from HALO Trust, Kabul, 7 August 2013.

[92] Interviews with MACCA implementing partners, Kabul, 15–22 May 2013.

[93] Email from Darvin Lisica, NPA, 13 April 2013.

[94] NPA, “Cluster Munitions Remnants in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A General Survey of Contamination and Impact,” 2011, p. 21,

www.npa-bosnia.org/images/PDF/Cluster-munition-remnants-in-BiH.pdf.

[95] Email from Miljenko Vahtarić, Croatian Mine Action Center, 4 July 2013; and statement of Croatia, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 17 April 2013.

[96] Email from Zana Kaka, Acting Program Officer, MAG, 13 March 2013.

[97] Email from Bazz Jolly, Operations/Program Manager, DDG Iraq, 17 July 2013; and email from Christina Bennike, Director of Donor Relations and Media, IMCO, 4 March 2013.

[98] NRA, “Sector Achievements: The Numbers,” received by email from NRA, 17 July 2013.

[99] LMAC, “2012 Annual Report Lebanon Mine Action Center,” Beirut, March 2013, p. 37; and response to Monitor questionnaire by Col. Hassan Fakih, LMAC, 24 May 2013.

[100] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Col. Hassan Fakih, LMAC, 24 May 2013.

[101] LMAC, “Lebanon Mine Action Strategy 2011–2020,” September 2011.

[102] Ibid.; LMAC, “2012 Annual Report Lebanon Mine Action Center,” Beirut, March 2013, p. 42; and interview with Brig. Gen. Imad Odeimi, Director, LMAC, in Geneva, 23 April 2013.

[103] LMAC, “2012 Annual Report Lebanon Mine Action Center,” Beirut, March 2013, p. 42. As of April 2013, the international operators are DanChurchAid, HI, NPA, and MAG. The lone national operator is Peace Generation Organization for Demining.

[104] LMAC, “Lebanon Mine Action Strategy 2011–2020,” September 2011.

[105] Interview with Brig. Gen. Imad Odeimi, LMAC, in Geneva, 23 April 2013; and LMAC, “2012 Annual Report Lebanon Mine Action Center,” Beirut, March 2013, p. 50.

[106] Torunn Aaslund, “Clearance of First Cluster Munition Strike Area Complete,” NPA, 17 April 2013, www.npaid.org/News/2013/Clearance-of-First-Cluster-Munition-Strike-Area-Complete.

[107] Email from Veselin Mijajlović, RCUD, 29 July 2012.

[108] NPA, “Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro,” July 2013, p. 27.

[109] Norway, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form F, 30 April 2012.

[110] Statement of Norway, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 17 April 2013.

[111] Response to Monitor questionnaire by Michelle Healy, Program Officer, UNMACC, Kinshasa, 29 April 2013.

[112] Ibid.

[113] Interview with Pascal Simon, UNMACC, in Geneva, 17 April 2013.

[114] Email from Oum Phumro, Deputy Director General, CMAC, 8 April 2013.

[115] Email from Slađana Košutić, SMAC, 30 April 2013; and emails from Vanja Sikirica, NPA, Belgrade, 10 April, 3 July, and 9 July 2013.

[116] Interview with Sr. Col. Nguyen Thanh Ban, PAVN Engineering Command, Hanoi, 18 June 2013.

[117] Information provided by Sr. Col. Phan Duc Tuan, PAVN in email received from Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation , Hanoi, 24 September 2012.

[118] Data compiled from results provided by operators to the Cluster Munition Monitor.