Landmine Monitor 2015

Casualties and Victim Assistance

©Loren Persi/ICBL-CMC, May 2015Albania's victim assistance focal point Veri Dogjani(right), a qualified medical doctor, discusses emergency response with NPA medical team in the field.

jump to Victim Assistance

Casualties

Landmines, victim-activated improvised explosive devices (IEDs), cluster munition remnants, [1] and other explosive remnants of war (ERW)—henceforth mines/ERW—remain a significant indiscriminate threat.

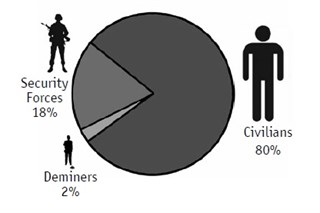

For 2014, the Monitor recorded 3,678 mine/ERW casualties marking a 12% increase from 2013. The percentage of civilian casualties, as compared to military and security forces, [2] was 80% in 2014 (where the civil status was known), almost identical to 2013. [3]

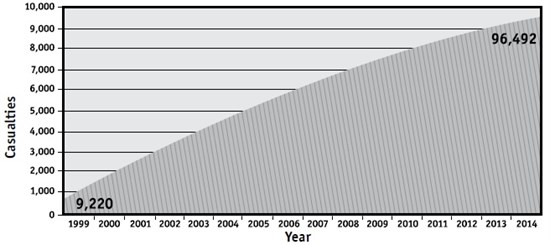

Number of mine/ERW casualties per year (1999–2014)

Despite ongoing casualties and the significant increase compared to 2013, 2014 still had the second lowest annual total of mine/ERW casualties recorded since 1999. There has been an overall trend of progressively fewer casualties since the Mine Ban Treaty entered into force 1999.

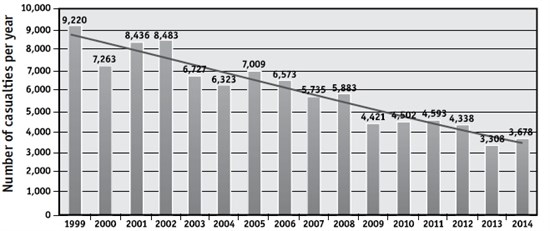

There were an average of 10 casualties per day in 2014, whereas in 1999 there was more than one mine/ERW casualty occurring each hour on average. [4] Yet the total global number of casualties continues to grow each year. Over 96,000 mine/ERW casualties have been recorded by the Monitor since its global tracking in began in 1999.

Cumulative total of mine/ERW casualties recorded 1999–2014 [5]

Casualties in 2014

Of the total of 3,678 mine/ERW casualties the Monitor recorded for 2014, at least 1,243 people were killed and another 2,386 people were injured; for 49 casualties it was not known if the person survived. [6] The Monitor recorded 3,308 casualties in 2013. In many states and areas, numerous casualties go unrecorded; therefore, the true casualty figure is likely significantly higher.

The data collected by the Monitor is the most comprehensive and widely used annual dataset of casualties caused by mines/ERW. [7] Casualties were identified in a total of 58 states and other areas in 2014. [8] Of the total casualties in 2014, 70% (2,593) occurred among States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty. [9]

States with 100 or more recorded casualties in 2014

|

States |

Number of casualties |

|

Afghanistan |

1,296 |

|

Colombia |

286 |

|

Myanmar |

251 |

|

Pakistan |

233 |

|

Syria |

174 |

|

Cambodia |

154 |

|

Mali |

144 |

Note: States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty are indicated in bold .

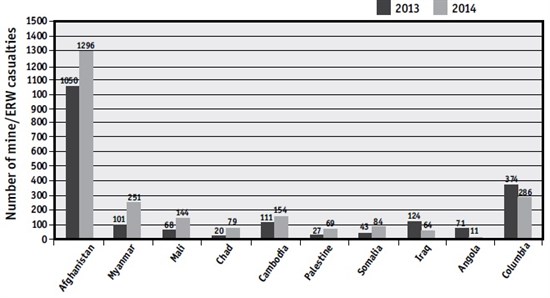

In 2014, there were far more victim-activated IED casualties in Afghanistan (809, compared to 567 in 2013), as well as a smaller increase in casualties caused by ERW (430, compared to 399 in 2013). In Mali, there was a jump in the number of mine casualties, thought to be due to antivehicle mines (92 in 2014, compared with 31 in 2013). In addition, victim-activated IED casualties were recorded in Mali for the first time (16). [10] In both Chad and Cambodia, the numbers of casualties from landmines, antivehicle mines, and ERW all increased compared to 2013. [11] One factor influencing the increased number of casualties reported in Myanmar appeared to have been more extensive data collection, with a larger number of organizations engaged and reporting on the landmine issue.

Greatest annual change in total mine/ERW casualties 2013–2014

However, it must be stressed that, as in previous years, the 3,678 mine/ERW casualties identified in 2014 only include recorded casualties. Due to incomplete data collection at the national level, the true casualty total is certainly higher. Based on the updated Monitor research methodology in place since 2009, it is estimated that there are up to approximately 1,000 additional casualties (25–30%) each year that are not captured in its global mine/ERW casualty statistics, with most occurring in severely affected countries and those experiencing conflict. The level of underreporting has declined over time as many countries have initiated and improved casualty data-collection mechanisms and the sharing of this data. In 2014, however, the number of casualties missed in national annual reporting is expected to be higher than average with more than 1,000 casualties (1,200–1,500), including many casualties from recently emplaced IEDs and booby traps in Iraq and Syria, yet to be accurately recorded. Some media reports quoted sources that said there had been hundreds of such casualties. [12]

Yet the 2014 estimate is a significant drop from the estimated total in 1999, when the monitor identified some 9,000 casualties, with another 7,000–13,000 annual casualties estimated as unrecorded.

Some significant country-level decreases in casualty totals in 2014 were likely due in part to conflict and insecurity reducing the possibility of data collection. In Yemen, reported casualties decreased from 55 in 2013 to 24 in 2014, significantly reduced from a peak of 263 in 2012. In Syria, a state not party to the Mine Ban Treaty that had seen a significant increase in mine/ERW casualties in 2013, casualty recording was reported to have been seriously hindered by the deteriorating security situation in 2014. Syria had 174 recorded casualties in 2014, compared to 201 in 2013. Just 19 casualties were recorded for Ukraine in 2014, although other reporting implied that there were hundreds of mine/ERW casualties through 2014 and into 2015, but the reports lacked sufficient detail to be included in the Monitor data set.

Fluctuations in annual casualties recorded in Angola (11 in 2014, 71 in 2013, and 34 in 2012) and in Iraq (64 in 2014, 124 in 2013, and 84 in 2012) are attributable to a lack of a reliable collection mechanism for casualty data in those countries. This causes variability in casualty totals and makes trends difficult to discern, as noted in the previous Landmine Monitor report. In addition, while data collection within Iran is thought to be quite complete, it has not been made available to the Monitor consistently. Consequently, the casualty data was often compiled from various sources, as was the case for 2014.

Casualty demographics [13]

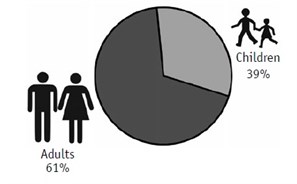

There were 1,038 child casualties in 2014, continuing minor annual decreases from 1,112 in 2013 and 1,272 in 2012. Child casualties in 2014 accounted for 39% of all civilian casualties for whom the age was known. [14] Since the Monitor began recording casualties in 1999, there has been an average of 31% child casualties among all casualties from mines/ERW. [15]

As in previous years, in 2014 the vast majority of child casualties where the sex was known were boys (81%). [16] There were 561 child casualties in Afghanistan in 2014, representing nearly half (46%) of all civilian casualties in that country where the age was known. It also constitutes over half (54%) of all child casualties recorded globally in 2014.

For more information on child casualties and assistance see the annual Monitor fact sheet on Landmines/ERW and Children.

Mine/ERW casualties by age in 2014 [17]

Mine/ERW incidents impact not only the direct casualties—the boys, girls, women, and men who were killed, as well as the survivors [18] —but also members of their families struggling under new physical, psychological, and economic pressures. As in previous years, there was no substantial data available on the numbers of those people indirectly impacted as a result of mine/ERW casualties.

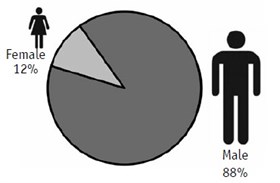

In 2014, the percentage of female casualties among all casualties for which the sex was known was 12% (378 of 3,234). This was the same percentage as in 2012 and in 2013. [19]

Mine/ERW casualties by sex in 2014 [20]

Between 1999 and 2014, the Monitor identified more than 1,600 deminers who were killed or injured while undertaking clearance operations to ensure the safety of civilian populations. [21] In 2014, there were 53 casualties identified among deminers (five deminers were killed and 48 injured) in 10 states, [22] a significant decrease in the number of demining casualties in the preceding two years: 85 in 2013, and 132 in 2012. It was also about half of the average of 105 casualties among deminers per year since 1999.

In 2014, the highest numbers of casualties among deminers were in Iran (17), Afghanistan (16), and Lebanon (six). Together, these three countries represented almost 75% of all deminer casualties globally in 2014. The 17 deminer casualties in Iran continued the trend of declining casualties among deminers since 2012; 687 deminer casualties have been identified in Iran since 2006. [23] Demining casualties in Afghanistan have been moderately consistent, with 18 casualties identified in 2013 and 16 in 2012.

Mine/ERW casualties by civilian/military status in 2014 [24]

Civilian casualties represented 80% of casualties where the civilian/military status was known (2,833 of 3,528).

The country with the most annual military casualties continued to be Colombia, with 187 in 2014. Mali, with 84 military casualties (including peacekeeping forces), was the next highest. The third highest number in 2014 was in Pakistan, with 75 military casualties, followed by Algeria (54) and Syria (52).

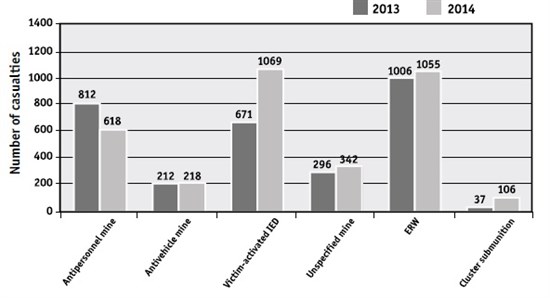

Victim-activated weapons and other explosive items causing casualties

In 2014, factory-made antipersonnel mines and victim-activated IEDs acting as antipersonnel mines caused the majority of all casualties (49% combined). [25] The percentage of total casualties from factory-made antipersonnel mines decreased (18% in 2014, down from 27% in 2013). [26] The percentage of casualties from victim-activated IEDs that act as antipersonnel mines increased significantly (up to 31%, from 22% in 2013). Afghanistan saw a large increase in the number of annual victim-activated IED casualties: 809 in 2014, from 567 in 2013, but less than the peak of 987 in 2012. This accounted for most of the increase in victim-activated IED casualties in 2014 globally.

In 2014, casualties from victim-activated IEDs were identified in nine states. [27] Starting in 2008, the Monitor began identifying more casualties from these improvised antipersonnel mines, likely due in part to an increase in their use and also to improved data collection that made it possible to better discern between factory-made antipersonnel mines and victim-activated IEDs, and between command-detonated IEDs and victim-activated IEDs.

Casualties by type of explosive device in 2014 [28]

In 2014, antivehicle mines killed and injured 218 people in 17 states and other areas, or 6% of casualties for which the device was known. [29] The states with the greatest numbers of casualties from antivehicle mines were Pakistan (64) and Cambodia (35). In 2013, antivehicle mines similarly caused 212 casualties, or 7% of casualties for which the device was known.

In 2014, 31% of casualties were caused by ERW in 41 states and areas, similar to the 34% recorded in 2013 and 31% of casualties in 2012. [30]

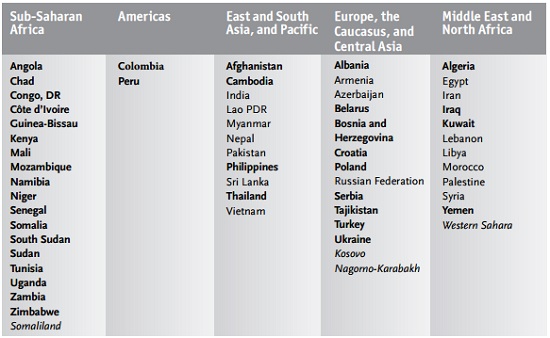

States/areas with mine/ERW casualties in 2014

Note: States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty are indicated in bold, other areas in italics

This overview reports on the annual status of coordination and planning efforts designed to improve access to services and programs for survivors of landmine and explosive remnants of war (ERW) for the year 2014, with updates into 2015 when possible. It covers the activities and achievements in 31 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant numbers of mine/ERW victims in need of assistance. It particularly assesses victim assistance in the context of the treaty’s Maputo Action Plan (2014–2019). [31] It also looks at the role of survivors in decision-making and other relevant matters of concern.

The Mine Ban Treaty is the first disarmament or humanitarian law treaty in which States Parties committed to provide“assistance for the care and rehabilitation, including the social and economic reintegration” of those people harmed by a specific type of weapon . [32] Victim assistance, in practice, addresses the overlapping and interconnected needs of persons with disabilities, including survivors [33] of landmines, cluster munitions, ERW, and other weapons, as well as people in their communities with similar requirements for assistance.

In addition, some victim assistance efforts reach family members and other people who have been killed or who have suffered trauma, loss, or other harm due to mines/ERW. All of these people are considered“mine victims” according to the accepted definition of the term, which includes survivors as well as affected families and communities—a lthough victim assistance efforts have mainly been limited to survivors to date.

The Monitor has tracked the progress of programs and activities that benefit mine/ERW survivors, families, and communities under the Mine Ban Treaty and its subsequent five-year action plans since 1999.

In June 2014 at the Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference in Maputo, all States Parties committed to the Maputo Action Plan, which includes a set of actions that would advance victim assistance through to 2019. [34] In order to replace the previous victim assistance standing committee, in Maputo States Parties also agreed to the formation of a new Committee on Victim Assistance that will“support States Parties in their national efforts to strengthen and advance victim assistance.” [35]

Despite years of financial shortages that reduced the availability of actual services, victim assistance efforts have remained vibrant. A wide range of activities demonstrated the continued will of States Parties, the UN, NGOs, and above all survivors’ own networks and representative organizations to“tangibly contribute, to the full, equal and effective participation of mine victims in society,” even when confronted with limited resources. [36]

As shown by the many successful practices and activities, victim assistance is not inherently complicated. However, many challenges remain to ensure access to sustainable services, to remove the barriers to the full participation of survivors in their societies, and to create acual improvements in their wellbeing. It will require active cooperation and stronger determination to overcome these challenges.

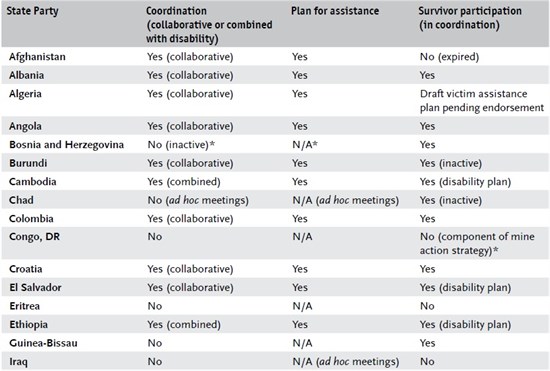

Mine Ban Treaty States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and needs

[Note: the table above was updated on 12 January 2016 to correct errors in the original publication]

At a symposium on the Maputo Action Plan’s victim assistance commitments, held by Thailand in Bangkok in June 2015, the ICBL highlighted that, in carrying out the plan, States Parties can apply the many years of training and capacity-building already provided during the life of the convention, including on improving planning, monitoring, and evaluation. [37] The ICBL also noted that a minimum level of clear and measurable objectives is needed. This was also highlighted in the evaluation of a multi-million dollar World Bank-funded rehabilitation system from the early days of victim assistance. In response to inadequate reporting on project achievements, the evaluation found that“a simple monitoring system focused upon a few key variables relating project outputs to intended outcomes would have sufficed.” [38]

The Maputo Action Plan provides a framework that allows States Parties to qualitatively assess progress in victim assistance, which they can attribute to the relevant actions that they take, even in the absence of existing measurable baselines. It calls for activities addressing the specific needs of victims while also emphasizing the necessity of simultaneously integrating victim assistance into other frameworks by incorporating relevant actions into the appropriate sectors, including disability, health, social welfare, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction. [39] States Parties commit to addressing victim assistance objectives“with the same precision and intensity as for other aims of the Convention.” [40]

The relevant content of the action points of the Maputo Action Plan, can be summarized as follows:

- Assess the needs; evaluate the availability and gaps in services; support efforts to make referrals to existing services.

- Enhance plans, policies, and legal frameworks.

- Ensure the inclusion and full and active participation of mine victims and their representative organizations in all matters that affect them; enhance capacity.

- Increase the availability of and accessibility to services, opportunities, and social protection measures; strengthen local capacities and enhance coordination.

- Address the needs and guarantee rights in an age- and gender-sensitive manner.

- Communicate time-bound and measurable objectives annually and report on measurable improvements in advance of the next Review Conference.

The Maputo Action Plan also affirms the need for States Parties to continue carrying out the actions of the previous five-year plan, the Cartagena Action Plan. The Cartagena Action Plan stressed the importance of the accessibility of services and information as well as the inclusion and participation of victims, particularly survivors, in all aspects of the treaty and its implementation. It emphasized that with regards to the assistance provided, there should be no discrimination against mine/ERW victims, among mine/ERW victims, nor between survivors with disabilities and other persons with disabilities. [41]

Assessing the needs

States Parties should assess needs for victim assistance—including through sex- and age-disaggregated data—and gauge the availability of services required. They should also use this opportunity to offer referrals to existing services. [42] [43]

Needs assessment methods were improving and were increasingly linked to the provision of services in States Parties in Southeast Asia. However, much more needed to be done in Afghanistan to improve data collection.

· In Afghanistan , no specific needs assessment surveys of mine/ERW survivors were conducted in 2014, but the relevant ministry registered persons with war-related disabilities and the dependents of persons killed in conflict in order for them to receive a monthly social security allowance. An independent assessment by the national corruption watch body reported that the registration practices were seriously flawed and that the social security registration system required a massive overhaul .

· In Cambodia , the national survivors’ network in partnership with the national mine action authority continued to conduct a large-scale survey on the quality of life for mine/ERW survivors and persons with disabilities. Data gathered was used to provide referrals, to enable follow-up, to address specific health, income-generating and educational needs, as well as to provide emergency food for those people in the most difficult situations.

· In Thailand , the relevant government agencies improved interagency coordination for the registration of new mine/ERW casualties, as well as follow-up for assistance and support. The national mine action center made follow-up visits and provided small emergency funds for the urgent needs of some survivors.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, needs assessments were geographically localized and survivor surveys progressively covered affected areas in several countries:

· In Angola , the national survey for identifying and registering mine/ERW survivors with disabilities and assessing needs had covered half of all 18 provinces in the country as of the end of 2014.

· In Burundi , the national mine action authority (DAHMI) [44] in collaboration with Handicap International (HI) identified survivors and assessed needs in three (Makamba, Rutana, and Ruyigi) of its 17 provinces.

· In Eritrea , the relevant government ministry and UNICEF carried out“mini assessments” during field monitoring activities.

· In Sudan , the UN continued to work with disabled persons’ organizations (DPOs) and social workers to identify the needs of mine/ERW survivors through individual case studies. This information was shared with the relevant ministry and the national mine action center.

· In Uganda , the national network of NGOs, called the Uganda Landmine Survivors Association (ULSA), undertook a mine/ERW survivor needs assessment in the remote Yumbe District.

Surveys that also enhanced survivors’ links with state-provided services were reported in the Americas:

· In Colombia , from mid-2014 the national mine action authority (DAICMA) [45] conducted a survey on the demographic, socio-economic, and cultural conditions of mine/ERW survivors, while informing them on how to register for services and benefits through the state process. Survey coverage increased.

· In El Salvador , the state-run Protection Fund held roundtable consultations with survivors’ associations on survivors’ needs and made individual visits to provide legal support and links to assistance.

· In Peru , the mine action center CONTRAMINAS [46] verified and updated information on mine/ERW survivors and their needs. It also visited the remote regions of Junín and Huancavelica to update information on registered survivors, provide medical assistance, and identify mine survivors who remained unregistered.

Progress in compiling data through assessment, although incomplete, was ongoing and making some progress in several countries in Europe:

· In Albania , an assessment of socio-economic and medical needs of marginalized ERW survivors was conducted in eight affected regions in 2013–2014 with the support of local government and branches of the national association of persons with work-related disabilities.

· Croatia progressed in the development of a unified database on casualties of mines/ERW and their families, with agreements made between relevant departments and agencies, a specific working group established, a dedicated staff member employed, and a combined database established . However, in 2015, there were insufficient funds to follow up with needs assessment in the field. The working group sought new approaches to implementing the needs survey, which was designed to inform the development of projects that would address the needs of survivors and their communities.

· In Serbia , the Ministry responsible for victim assistance announced plans to establish a database of members of disabled persons’ organizations, to be updated regularly on the current needs of individuals.

· Turkey continued to monitor and report on survivors receiving care through the military medical system in 2014. In 2015, the national mine ban campaign in cooperation with the national disability association were collecting data on survivors in refugee camps in eastern Turkey.

In the Middle East and North Africa there was notably increased sharing and use of casualty data from recent surveys, in addition to some ongoing data collection:

· In Algeria , data from HI’s 2012 survivor identification process was used in the development of the new victim assistance action plan (March 2014) and in the implementation of economic inclusion projects for mine/ERW survivors and persons with disabilities, funded by the relevant government ministry and the European Union.

· In Iraq , the national mine action authority based in Bagdad continued mine/ERW survivor survey efforts in 2014 and into 2015. A Basrah province survey was ongoing in 2015, to be completed in 2016. It provided data and information on needs from the national survey and assessment to the relevant ministries. Mine action authorities also exchanged survivor information with the health ministry’s national injury surveillance system.

· In Yemen , a significant number of mine/ERW survivors were registered in Abyan in 2013, while in 2014 some additional survivors were registered during the course of a victim assistance team conducting medical examinations and providing support.

Additionally , questions about disability, which were also relevant to survivors, were included in preparations for upcoming national censuses in El Salvador, Ethiopia, and Uganda. This was encouraged and supported by survivor’s organizations. In Peru, the national disability council (CONADIS), [47] a member of the national Victim Assistance Consultative Committee, was also working on a disability census.

Enhancing plans, policies, and legal frameworks

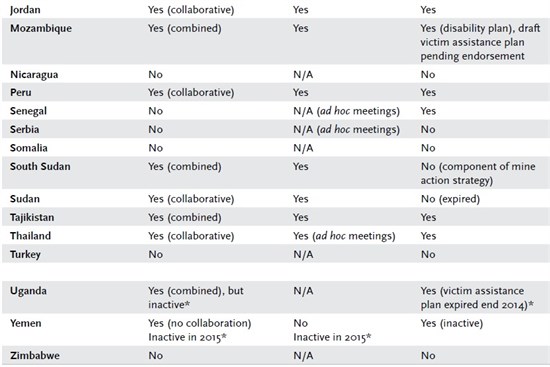

Status of victim assistance coordination in 2014/2015

Note: Changes since Landmine Monitor 2014 marked with *. N/A = There was no active coordination mechanism in which survivors could participate. Ad hoc meetings = While there was no active coordination mechanism, survivors and their representative organizations met with relevant government authorities.

Coordination

States Parties committed to enhancing coordination activities in order to increase the availability and accessibility of services that are relevant to mine victims. [48] In 2014 and into 2015, 18 of the 31 States Parties had active victim assistance coordination mechanisms or disability coordination mechanisms that considered the issues relating to mine/ERW survivors’ needs. [49]

In Iraq, Senegal, Serbia, and Thailand there were no official multi-sectorial coordination meetings, but ad hoc meetings continued to take place during 2014. In the Kurdistan region of Iraq, coordination was hampered by significant funding capacity constraints. A victim assistance coordination mechanism was established in Serbia in early 2015. Ad hoc victim assistance meetings also began in Chad, taking place during 2014. In Somalia, a victim assistance and disability working group met for the first time in May 2014 and was intended to meet quarterly, but no meetings have taken place since .

In Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), victim assistance coordination was put on hold in early 2014. The coordination mechanism for victim assistance in DR Congo was dissolved in 2013, and the closure of the UNMAS office in Kinshasa in 2014 saw coordination moved to the physical rehabilitation-focused cluster on disability (led by the World Health Organization, WHO), where victim assistance issues were not specifically addressed. In South Sudan, t he victim assistance and disability working group held only one meeting between September 2014 and June 2015 due to funding difficulties. Previously, it was reported to have held monthly meetings. There were no meetings of the intersectoral disability committee responsible for victim assistance coordination in Uganda in 2014; meetings had becoming increasingly less frequent since 2013, also due to a lack of funding. In Yemen, coordination ceased due to armed conflict in 2015, not long after having been reactivated in 2013.

Among the 18 States Parties with active victim assistance coordination in 2014, all the national coordination mechanisms were reported to have either collaborated with, or been included as part of, an active disability coordination mechanism. In six States Parties, the designated national coordination body for victim assistance continued to also be the coordination mechanism for disability issues into 2015. [50]

Plans and objectives

Actions #13 and #14 of the Maputo Action Plan call on States Parties to have time-bound and measurable objectives to implement national policies and plans that will tangibly contribute to the main goals of victim assistance.

In 2014, of the 31 States Parties with significant numbers of survivors, 19 had plans with objectives that address the needs and promote the rights of mines survivors. [51] Plans in Burundi, Chad, and Yemen remained on hold, due to either a lack of resources and/or armed conflict.

Actions to respond to the needs of mine survivors had been incorporated into the national disability plans in Cambodia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, and South Sudan, although these states did not have a distinct victim assistance plan. Algeria and Mozambique had developed victim assistance plans, which were pending official approval. Colombia, Peru, and Tajikistan had both a national victim assistance plan and disability plans and policies that take into account the needs and rights of mine/ERW survivors. [52]

In June 2014, Serbia announced that it had initiated the development of a national victim assistance plan through the newly forming working group on victim assistance.

Availability of and accessibility to services

Action #15 of the Maputo Action Plan commits States Parties to“increase availability of and accessibility to appropriate comprehensive rehabilitation services, economic inclusion opportunities and social protection measures…including expanding quality services in rural and remote areas and paying particular attention to vulnerable groups.”

Updates on the availability and accessibility of comprehensive rehabilitation for mine/ERW survivors and other persons with disabilities are included in a separate report produced by the Monitor. [53] This report,“Equal Basis 2015: Inclusion and Rights in 33 Countries,” presents progress in the relevant States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty and Convention on Cluster Munitions [54] in the context of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

The Monitor website includes detailed country profiles discerning progress in victim assistance in some 70 countries, including both States Parties and states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty and the Convention on Cluster Munitions. [55]

Full and active participation

Action #16 of the Maputo Action Plan commits States Parties to ensure the“full and active participation of mine victims and their representative organizations in all matters that affect them.”

Mine/ERW survivors’ representatives were members of most existing victim assistance coordination mechanisms. However, there remains a long way to go for survivors to be effectively included in coordination roles in a way that their input is listened to, understood, and acted upon with tangible measures in the context of the design and implementation of victim assistance objective s . Most States Parties are yet to demonstrate that they are doing their utmost to enhance the capacity of survivors for their effective participation, or to specify the methods that they are using to build that capacity.

Among the 18 States Parties with active victim assistance coordination during 2014, all but one (Yemen) included survivors in these mechanisms. However, in many cases there remained a need to build the capacity of survivors’ representatives and raise awareness in the coordination bodies in order for inclusion to be fuller and participation more active.

Mine/ERW survivors also participated actively in Mine Ban Treaty and other disarmament and disability rights coordination and campaigning, as well as in matters of peacemaking and peace-building in many countries, including in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Serbia, Senegal, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Uganda. In Colombia, members of National Network of Landmine Victims and Survivors’ Organizations, formed in December 2013, represented the perspectives of mine/ERW survivors in the Colombian peace process national committee, as well as at the peace negotiations in Havana, Cuba in 2015.

The strong involvement of female mine/ERW survivors in peace issues was evident in t he Director of the Uganda Landmine Survivors Association—who is also an ICBL Ambassador—joining the 2014 Women Peace Makers Program of the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice at the University of San Diego (US) . A female survivor leader from Thailand also participated in a seminar at the UN in New York in July 2014, as part of Thailand’s efforts to promote the women, peace, and security agenda associated with Security Council Resolution 1325.

In the majority of the 31 States Parties, survivors continued to be involved in implementing many aspects of victim assistance, including physical rehabilitation, peer support and referral, income-generating projects, and needs assessment data collection. [56]

Communicating objectives and reporting improvements

After 15 years of Mine Ban Treaty reporting, there was no agreed format for victim assistance reporting. Many States Parties reported progress similarly to the way they had in past years, by including a mix of casualty data, updates on victim assistance services provided, and occasionally information on laws and policies. While more than half of the most-affected 31 States Parties had included some information on victim assistance activities in their Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 reports covering calendar year 2014, [57] no States Parties had reported directly on their time-bound and measurable objectives by the ambitiously narrow timeframe of 30 April 2015, as specified in Maputo Action Plan Action #13. However, according to the plan, the objectives should be updated, their implementation monitored, and progress reported annually. Each year,“enhancements” to plans, policies, and legal frameworks and budgets for the implementation of those plans, policies, and legal frameworks should also be reported. By the next reporting period, States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and needs for assistance will have less than four years to adopt and apply an adequate reporting method for indicating that their efforts have improved the well-being and guaranteed rights of survivors, families, and communities before the next Review Conference.

Gender considerations

The Maputo Action Plan speaks of“the imperative to address the needs and guarantee the rights of mine victims, in an age- and gender-sensitive manner.” [58] While men and boys are the majority of reported casualties, women and girls may be disproportionally disadvantaged as a result of mine/ERW incidents and suffer multiple forms of discrimination as survivors. To guide a rights-based approach to victim assistance for women and girls, States Parties can apply the principles of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Implementation of CEDAW by States Parties to that convention should ensure the rights of women and girls and protect them from discrimination and exploitation. [59] The Committee of CEDAW General Recommendation 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict, and post-conflict situations and General Recommendation 27 on older women and protection of their human rights, are also particularly applicable .

Some States Parties have begun to address gender issues, often with assistance from the NGO Gender and Mine Action Programme. For example, in 2014, the Mine Action Coordination Center of Afghanistan developed and adopted a Gender Mainstreaming Strategy for 2014–2016 (including victim assistance) and established focal points and an implementation working group.

Age considerations

Children, and in particular boys, are one of the largest groups of casualties and survivors. Child survivors have specific and additional needs in all aspects of assistance. Incremental progress in addressing the specific needs of child survivors was reported in some domains of assistance, particularly psychosocial support and education. The annually updated Monitor fact sheet on the Impact of Mines/ERW on Children contains more details on issues pertaining to children, youths, and adolescents.

Special issues of concern: displacement, conflict, and humanitarian emergencies

This Monitor reporting period was marked by growing numbers of refugees and displaced persons resulting from conflict, as well as by the impact of conflict and natural disasters gravely affecting victim assistance efforts in a number of States Parties. During natural disasters, humanitarian emergencies, and times of armed conflict or occupation, mine/ERW survivors face heighted challenges to having their rights respected and fulfilled, as well as increased barriers to accessing adequate and appropriate services. [60]

In October 2015, flash rains and massive floods destroyed houses and infrastructure in the Sahrawi refugee camps where hundreds of survivors live with little outside support. The camps are situated near Tindouf in Algeria, near Western Sahara. Earlier in 2015, the World Food Programme in Algeria had to reduce the number of essential food items distributed to Sahrawi refugees, including mine/ERW survivors, by 20%. UN agencies present in the camps were jointly advocating for the most basic needs of these refugees to be covered and not to be forgotten. [61]

In 2014, catastrophic flooding in BiH and Serbia affected a significant number of landmine survivors and their families, some of whom lost their homes and other resources. About half of all known survivors in BiH were reported to be in flood-affected areas. The flooding disrupted victim assistance activities in both countries.

In Serbia, floods caused both the state and many local NGOs to re-prioritize their programming to focus on relief for flood victims. This caused a general reduction in services and programs for Serbian mine/ERW survivors, as funds were diverted for emergency relief. During relief efforts, media statements by the mine action center of BiH urged special attention to the needs of mine/ERW survivors. In Serbia, survivors also participated in relief efforts, including by distributing food and water, and the survivors’ organizations reallocated project funding to assist those most affected.

The conflict in Syria has caused a massive displacement crisis. Refugee host countries, principally Mine Ban Treaty States Parties Turkey, Jordan, and Iraq, as well as Lebanon (a State Party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions), have received large numbers of persons who have fled Syria. While all these host countries have victim assistance commitments and obligations, the influx of refugees created additional challenges in providing assistance and access to services for landmine survivors and other refugees with disabilities . In Iraq, healthcare centers and hospitals in the Kurdistan region were overwhelmed by the number of refugees in need entering from Syria during 2014, especially when combined with the increase in internal displacement. In Jordan, wounded Syrians received immediate medical care and humanitarian organizations provided some psychological support and rehabilitation services for war-injured persons. In Turkey, i nitial emergency medical care is provided locally, but the costs of physical rehabilitation, mobility aids, and plastic surgery were not covered by government services, and the availability of these relied on non-governmental and international organizations.

Conflict, insecurity, and armed violence severely disrupted the availability and delivery of services in South Sudan. This was also reported to be the case in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen in 2014 and 2015.

NOTES:

The table "Mine Ban Treaty States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and needs" was corrected on 12 January 2016.

The table ""States/areas with mine/ERW casualties in 2014" was corrected on 28 March 2016, indicating casualties occurred in Colombia, not in Chile.

[1] Casualties from cluster munition remnants are included in the Monitor global mine/ERW casualty data. Casualties occurring during a cluster munition attack are not included in this data; however, they are reported in the annual Cluster Munition Monitor report. For more information on casualties caused by cluster munitions, see ICBL-CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2015 , www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2015/cluster-munition-monitor-2015/casualties-and-victim-assistance.aspx .

[2] Security forces include police and representatives of non-state armed groups.

[3] The percentage of civilian casualties was 79% in 2013, 81% in 2012, and 70% in 2011. Since 2005, civilians have represented approximately 73% of casualties for which the civilian status was known. From 1999–2003, the percentage of civilian casualties averaged 81% per year.

[4] In 1999, the Monitor identified 9,220 mine/ERW casualties. Given significant improvements in data collection since 1999, with a higher proportion of casualties now being recorded, the decrease in casualties is likely even more significant.

[5] Figures include individuals killed or injured in incidents involving devices detonated by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person or a vehicle, such as all antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, abandoned explosive ordnance (AXO), unexploded ordnance (UXO), and victim-activated IEDs. AXO and UXO, including cluster munition remnants, are collectively referred to as ERW. Cluster munition casualties are also disaggregated and reported as distinct from ERW where possible. Not included in the totals are: estimates of casualties where exact numbers were not given, incidents caused or reasonably suspected to have been caused by remotely-detonated mines or IEDs (those that were not victim-activated), and people killed or injured while manufacturing or emplacing devices. For more details on casualty figures or sources of casualty data by country or area, see country profiles on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/country-profiles.aspx .

[6] This is among the lowest number of unknowns since Monitor recording began in 1999.

[7] For the year 2014, the Monitor collected casualty data from 25 different national or UN mine action centers. The Monitor also collected data on casualties from various mine clearance operators and victim assistance service providers, as well as from a range of national and international media sources. Mine action centers registered 835 of the 3,678 casualties identified in 2014. The Monitor identified 591 mine/ERW casualties in 2014 through the media that had not been collected via official data-collection mechanisms. The majority of these casualties occurred in countries without any data-collection mechanism.

[8] The Monitor first recorded 72 states in which mine/ERW casualties were identified in 1999.

[9] Casualties were identified in the following 37 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty in 2014: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DR Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Kenya, Kuwait, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Yemen, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

[10] The remainder of the increase for Mali was casualties caused by ERW: 33 in 2014, up from 21 in 2013. The number of casualties from unknown devices declined: 3 in 2014, down from 16 in 2013.

[11] For Chad the following casualties were reported: 46 via unspecified mine types in 2014, and 20 in 2013; 20 antipersonnel mine in 2014, and none (differentiated) in 2013; and 13 ERW in 2014, and none (differentiated) in 2013. Cambodia reported the following casualties: 37 via antipersonnel mine in 2014, and 25 in 2013; 35 antivehicle mine in 2014, and 24 in 2013; 81 ERW in 2014, and 60 in 2013. The remaining casualties in Cambodia were from unexploded submunitions, one in 2014, and three in 2013.

[12] However, it was often not clearly reported whether devices were victim-activated.

[13] The Monitor tracks the age, sex, civilian status, and deminer status of mine/ERW casualties, to the extent that data is available and disaggregated.

[14] Child casualties are defined as all casualties where the victim is less than 18-years of age at the time of the incident.

[15] The Monitor identified more than 1,500 child casualties in 1999, and more than 1,600 in 2001.

[16] The sex of 33 child casualties was not recorded.

[17] This includes only the civilian casualties for which the age was known.

[18] A survivor is a person who was injured by mines/ERW and lived.

[19] For 444 casualties the sex was not known.

[20] This includes only the casualties for which the sex was known.

[21] There were 1,623 casualties among deminers from 1999 through 2014. Since 1999, the annual number of demining casualties identified has fluctuated widely, making it difficult to discern trends. Most major fluctuations have been related to the exceptional availability or unavailability of deminer casualty data from a particular country in any given year and therefore cannot be correlated to substantive changes in operating procedures, in international demining standards, or demining equipment.

[22] Casualties among deminers occurred in Afghanistan, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iran, Lebanon, Mozambique, Tajikistan, Thailand, Zimbabwe, and Somaliland.

[23] No data on deminer casualties in Iran prior to 2006 was available to the Monitor for inclusion in this report. Even based on partial data, Iran exceeded all countries in the total number of demining casualties since 1999. Afghanistan, with the second highest number of deminer casualties, has recorded 491 since 1999.

[24] This includes only the casualties for which the civilian/military status was known.

[25] Calculated for casualties for which the specific type of victim-activated explosive item was known.

[26] In 2014, there were casualties from factory-made antipersonnel mines in 26 states and areas: Afghanistan, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, India, Iran, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mozambique, Myanmar, Pakistan, Peru, Senegal, South Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Zimbabwe and three other areas: Nagorno-Karabakh, Somaliland, and Western Sahara.

[27] Afghanistan, Algeria, India, Mali, Pakistan, Philippines, Russian Federation, Thailand, and Tunisia.

[28] This includes only the casualties for which the device type was known. The number of cluster submunition casualties was incomplete because casualties were not differentiated from other ERW casualties.

[29] In 2014, casualties from antivehicle mines were identified in the following states: Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Egypt, Guinea-Bissau, Iran, Morocco, Myanmar, Pakistan, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Ukraine, and two other areas: Nagorno-Karabakh and Western Sahara.

[30] In 2014, casualties from ERW were identified in the following states: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DR Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, India, Iran, Iraq, Kenya, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Mozambique, Namibia, Nepal, Pakistan, Palestine, Peru, Poland, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia, and two other areas: Kosovo and Somaliland. In addition to other types of ERW, casualties of unexploded submunitions were identified in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Iraq, Kosovo, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, South Sudan, Syria, and Vietnam. For more information on casualties caused by unexploded submunitions and the annual increase in those casualties recorded for the year 2014, see ICBL-CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2015 , www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2015/cluster-munition-monitor-2015/casualties-and-victim-assistance.aspx

[31] This corresponds with Actions 12-18 of the Maputo Action Plan. The Monitor reports on the following 31 Mine Ban Treaty States Parties in which there are significant numbers of survivors: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. This list includes 29 States Parties that have indicated that they have significant numbers of survivors for which they must provide care as well as Algeria and Turkey , which have both reported hundreds or thousands of survivors in their official landmine clearance deadline (Mine Ban Treaty Article 5) extension request submissions. Algeria, Mine Ban Mine Ban Treaty Revised Article 5 Extension Request, 31 March 2011, www.apminebanconvention.org/fileadmin/pdf/other_languages/french/MBC/clearing-mined-areas/art5_extensions/countries/Algeria-ExtRequest-Revised-17Aug2011-fr.pdf ; and Turkey, Mine Ban Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 Extension Request, 28 March 2013, www.apminebanconvention.org/fileadmin/APMBC/clearing-mined-areas/art5_extensions/countries/Turkey-ExtRequest-Received-29Mar2013.pdf .

[32] Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction, (Mine Ban Treaty) Article 6.3, www.apminebanconvention.org/overview-and-convention-text/ .

[33] A“survivor” is a person who was injured by mines/ERW and lived.

[34]“Maputo Action Plan,” Maputo, 27 June 2014, www.maputoreviewconference.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC3/3RC-Maputo-action-plan-adopted-27Jun2014.pdf .

[35]“Decisions on the Convention’s Machinery and Meetings,” Maputo, 27 June 2014, p. 5, www.maputoreviewconference.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC3/3RC-Decisions-Machinery-27Jun2014.pdf .

[36] Maputo Action Plan, Action #13. Until the Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference in 2014 there had been a Standing Committee on Victim Assistance and Socio-Economic Reintegration, which was originally titled the Standing Committee of Experts on Victim Assistance, Socio-Economic Reintegration, and Mine Awareness.

[37]“Victim Assistance & the Framework of Maputo Action Plan,” Presentation of ICBL, Bangkok, 15 June 2015.

[38] Word Bank, Independent Evaluation Group,“Implementation Completion Report (ICR) Review - War Victims Project ,” 12 December 1999, http://lnweb90.worldbank.org/oed/oeddoclib.nsf/InterLandingPagesByUNID/8525682E0068603785256913006EF367 .

[39] Actions #12 to #18 of the Maputo Action Plan.

[40]“Maputo Action Plan,” Maputo, 27 June 2014, p. 3.

[41]“Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014: Ending the Suffering Caused by Anti-Personnel Mines,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009 (hereafter referred to as the“Cartagena Action Plan”).

[42] According to Action #12 of the Maputo Action Plan.

[43] Country profiles are available on the Monitor website providing more details on all countries highlighted in this chapter, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/country-profiles.aspx .

[44] Direction de l’Action Humanitaire contre les Mines et Engins non explosés.

[45] Dirección para la Acción Integral contra Minas Antipersonal.

[46] Centro Peruano de Accion Contra las Minas Anti-Personal.

[47] Consejo Nacional para la Integración de la Persona con Discapacidad.

[48] According to the ongoing Cartagena Action Plan victim assistance commitments and supported by Action#15 of the Maputo Action Plan.

[49] Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Burundi, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Yemen. States with no known or no active coordination mechanism for victim assistance in 2014: BiH, Chad, DR Congo, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Nicaragua, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, Turkey, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

[50] Cambodia, Ethiopia, Mozambique, South Sudan, Tajikistan, and Uganda.

[51] Albania, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uganda, and Yemen. States with no plan: Afghanistan, DR Congo, Eritrea, Iraq, Nicaragua, Serbia, Somalia, Sudan, Turkey, and Zimbabwe.

[52] In Colombia and El Salvador, planning of mine/ERW victim assistance was also integrated into efforts to address the needs of armed conflict victims more generally.

[53] See also, ICBL-CMC,“Equal Basis 2014: Access and Rights in 33 Countries ,” 12 December 2014, www.icbl.org/en-gb/news-and-events/news/2014/equal-basis-2014-access-and-rights-in-33-countries.aspx .

[54] The 31 Mine Ban Treaty States Parties detailed here, plus Lao PDR and Lebanon (States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions), with significant numbers of cluster munition, landmine, and ERW victims. The "Equal Basis 2015" report is scheduled for publication in December 2015.

[55] Country profiles are available on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/country-profiles.aspx . Findings specific to victim assistance in states and other areas with victims of cluster munitions are available through Landmine Monitor 2015 ’s companion publication; ICBL-CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2015 (Geneva: ICBL-CMC, August 2015), www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2015/cluster-munition-monitor-2015.aspx .

[56] Participation in service and program implementation was reported in at least the following 26 States Parties: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DR Congo, Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uganda, and Yemen.

[57] The States Parties that provided some updates on victim assistance were: Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Zimbabwe. Sudan reported that it did not have any victim assistance activities due to a lack of funding, and Thailand reported on a one-time event.

[58] Maputo Action Plan Action #17.

[59] As of 1 June 2015, CEDAW had 189 States Parties. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women , New York, 18 December 1979 , treaties.un.org/pages/viewdetails.aspx?src=treaty&mtdsg_no=iv-8&chapter=4&lang=en .

[60] Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor,“Landmines/ERW, Refugees, and Displacement,” 20 June 2015,” www.the-monitor.org/media/2034850/MonitorBriefingPaper_Refugees_20June2015_final2.pdf ; and“Victim Assistance and CRPD Article 11: Situations of risk and humanitarian emergencies,” 25 June 2015, www.the-monitor.org/media/2034853/MonitorBriefingPaper_VAandArticle11_25June2015.pdf .

[61] World Food Programme,“UN Agencies In Algeria Urge Continued Food Assistance To Refugees From Western Sahara,” 25 February 2015, www.wfp.org/news/news-release/un-agencies-algeria-urge-continued-food-assistance-refugees-western-sahara .