Cluster Munition Monitor 2016

Casualties and Victim Assistance

Cluster Munition Casualties (Casualties in 2015) | Victim Assistance (Introduction | Victim assistance in the Dubrovnik Action Plan | Improvement in the quantity and quality of assistance | Respect for human rights | Exchange of information| Involvement of victims | Support for victim assistance programs | Demonstration of results in Article 7 transparency report)

The total number of cluster munition casualties for all time recorded by the Monitor had surpassed 20,300 as of the end of 2015.[1] This total includes casualties recorded as directly resulting from cluster munition attacks or other deployment of cluster munitions, as well as casualties that occurred from cluster munition remnants.[2] Casualties directly caused by use have been grossly under-reported in data and in many estimates, including those casualties among military and security personnel. As many casualties still go unrecorded, a summary total of more than 55,000 cluster munition casualties globally, calculated from various country estimates, provides a better indicator of the sum over time. Global projections of cluster munition casualties range as high as 85,000 casualties or more, but some of those projected country totals are based on extrapolations from limited data samples and the data may not be representative of national averages or the actual number of casualties.[3]

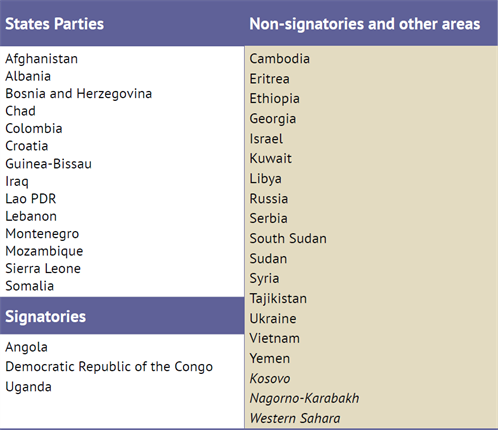

States and other areas with cluster munition casualties (as of 31 December 2015)[4]

Note: other areas are indicated in italics.

The Monitor provides the most comprehensive statistics available on cluster munition casualties recorded annually over time, in individual countries, and aggregated globally. The present total of 20,302 cluster munition casualties from the mid-1960s through the end of 2015, recorded in 33 countries and three other areas, is far greater than the 13,306 recorded cluster munition casualties identified before the signing of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in 2008.[5] The increase is mostly due to more casualties from the past being identified since the adoption of the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Deplorably, however, some 2,600 newly occurring casualties were recorded in the period 2010–2015.[6]

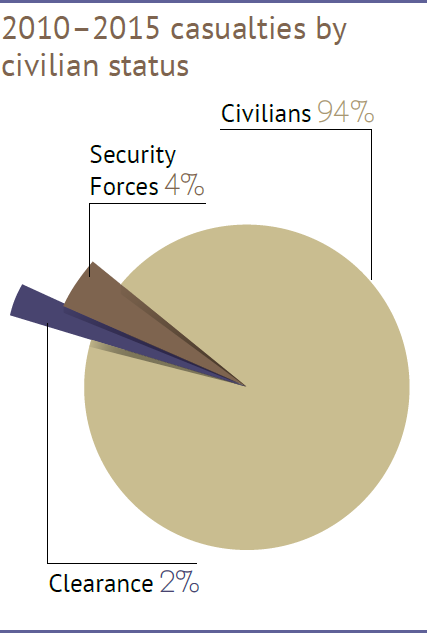

From 2010–2015, civilians were the vast majority (94%) of all cluster munition casualties where the status was recorded. Cluster munition clearance personnel—humanitarian deminers and explosive ordinance disposal (EOD) experts—accounted for 2%, and security forces—military and other security personnel as well as non-state armed group (NSAG) actors—accounted for 4%.[7] The high percentage of civilian casualties is consistent with the findings based on analysis of historical data reported prior to entry into force of the convention.[8]

2010–2015 casualties by civilian status

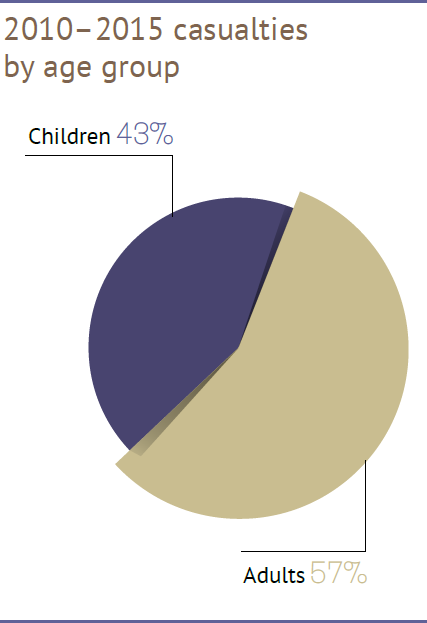

Children under 18 years of age accounted for more than 40% of all cluster munition casualties in 2010–2015, in countries where casualties from submunitions were disaggregated and details known.[9]

2010–2015 casualties by age group

The vast majority (15,852) of all reported casualties to date were caused by cluster munition remnants—typically explosive submunitions that failed to detonate during strikes. Another 3,126 casualties occurred during the deployment of cluster munitions (mostly attacks but also the dumping of cluster munitions prior to aircraft landing).[10] More recent improvements in data collection highlight the widespread failure to record cluster munition casualties in past conflicts, particularly casualties that occurred during airstrikes and shelling in Asia and the Middle East. The number of states with cluster munition victims is also likely to be greater than those currently identified.[11]

Despite improvements in data collection methods since the entry into force of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, new casualties from cluster munitions occurring each year remained underreported. In many countries’ data, cluster munition casualties are not recorded separately from casualties of other types of unexploded ordnance. The actual annual total of submunition casualties is likely much higher than recorded, as is the number of countries in which they were reported.

For calendar year 2015, the Monitor recorded 417 cluster munition casualties. These cluster munition casualties were recorded in at least eight countries and two other areas: Afghanistan (four), Cambodia (two), Chad (four), Lebanon (13), Lao PDR (18), Syria (248), Ukraine (19), Yemen (104), as well as Nagorno-Karabakh (one), and Western Sahara (four). Of the total, casualties in 2015, 343 occurred during cluster munition attacks and 74 were from unexploded submunitions. Due to the lack of consistency in the availability and disaggregation of data on cluster munition casualties annually, comparisons with previous annual reporting are not believed to be necessarily indicative of trends.[12]

Civilians made up 97% of all cluster munition casualties in 2015 where the status was known (388 civilians, 14 security forces, and 15 without recorded status). In 2015, children accounted for 36% of all civilian cluster munition casualties, where the age group was reported (102 children among 286 civilian casualties of known age), and women and girls made up 23% of civilian casualties, where sex was recorded (41).[13]

Despite the overall ambiguity in many reporting systems, the effects of unexploded submunitions clearly continued long after the munitions were used, disproportionately affecting civilians, including children. This was the case in State Parties Lebanon and Lao PDR, for example. In Lebanon, unexploded submunitions were the cause of more than three-quarters of all mine and explosive remnants of war (ERW) casualties in 2015.[14] Children were the most harmed by far, making up 12 of the 13 (92%) recorded cluster munition casualties in Lebanon for 2015. In Lao PDR, 18 unexploded submunition casualties were disaggregated among a total of 42 ERW casualties recorded in 2015. Another 17 casualties were suspected to have been due to unexploded submunitions, although the device involved could not be adequately determined. Three-quarters of cluster munition casualties in Lao PDR in 2015 were children (12 of 18, or 67%).

Casualties from cluster munition attacks were recorded in Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen in 2015. All three states also reported unexploded submunition casualties in 2015. In Syria, 231 casualties of cluster munition attacks and 17 casualties of unexploded submunitions were reported during 2015. As has been the case each year since 2012, Syria had the highest annual total of reported cluster munition casualties.[15] In Ukraine, 18 casualties of cluster munition attacks were reported in January and February 2015 alone (after which use was not reported); at least one civilian casualty from unexploded cluster munitions was identified. In Yemen, 94 casualties from attacks were reported in 2015, and 10 from unexploded submunitions. Civilians made up 89% of the total of cluster munition casualties recorded both from attacks and unexploded submunitions in Yemen.[16]

In 2015, many casualties from attacks were recorded in and near market places, schools, and hospitals. For example in Syria, the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) documented cluster munition attacks on a makeshift hospital in Al-Musayfrah city, Daraa governorate in February; a displaced persons camp in Younseyeh village in Idlib governorate in November killed eight and injured 43; and a cluster munition attack on a displaced persons camp near Al-Naqeer in Idlib governorate killed five people and injured 20 in October.[17] Human Rights Watch documented cluster munition attacks on two schools in Douma in December that killed at least eight children and two teachers.[18] In Yemen, at least two casualties were wounded in a cluster munition attack near the Al-Amar village in Saada governorate on market day on 27 April.[19] In Ukraine, a woman and child were killed in playground by a school in cluster munition rocket attacks on Artemivsk in the Donetsk region on 13 February.[20]

Prior to entry into force of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in 2010, the civilian casualties caused by cluster munition attacks hitting markets, hospitals, and schools were known due to many widely reported events. The casualties from the following examples of such attacks are included in the Cluster Munition Monitor global total for all time: cluster munition attacks on Gori, Georgia in 2008, killed six civilians in the city square, including people gathered to collect food contributions from a local administration office.[21] In 1999, at least 137 people were killed and some hundreds more reported injured by cluster munitions in a market in Grozny, Chechnya. A maternity ward was also hit during the attacks on Grozny, resulting in 28 casualties (13 women and 15 children).[22] Also in 1999, cluster munition attacks on Niš, Serbia killed 14 people, seven at the city marketplace and another seven at the hospital; 57 people were injured in the attacks.[23] Cluster munitions attacks on Mekele, Ethiopia in 1998, hit a school and its urban neighborhood, killing 53 civilians (including 12 school children); another 185 civilians were injured (including 42 children).[24] In 1995, a cluster munition attack struck a displaced persons camp in Živinice, Bosnia and Herzegovina, killing 10 people and injuring 34.[25]

The Convention on Cluster Munitions requires that States Parties with cluster munition victims implement specific activities to ensure adequate assistance in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law.[26] The convention’s victim assistance obligations have been elaborated in the Dubrovnik Action Plan adopted by States Parties at the First Review Conference of the convention in September 2015.[27]

The first international treaty to make the provision of assistance to victims of a given weapon a formal requirement for all States Parties with victims, the Convention on Cluster Munitions continues to set the highest standards in requirements for victim assistance.[28] By codifying the international understanding of victim assistance and its components and provisions, the Convention on Cluster Munitions extended the reach and understanding of the growing norm on victim assistance. The convention demands that differences in treatment between cluster munition victims with disabilities and other persons with disabilities be based only on their needs.[29] It reflects the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ (CRPD's) general principle prohibiting “discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability.”[30] The preamble of the Convention on Cluster Munitions also highlights its close relationship with the CRPD.[31]

The 14 States Parties with responsibility for cluster munition victims should identify the resources available, as well as mobilize international cooperation needed for victim assistance activities. States Parties in a position to provide international cooperation are required to provide such support in order for States Parties with cluster munition victims to fulfill their obligations. Addressing the needs identified by States Parties and cluster munition victims will require that significantly greater targeted resources be made available by both affected and donor States Parties.

Monitor research has shown that over time the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and victim assistance in humanitarian disarmament more broadly, has contributed to making more resources available to survivors, as well as to people with similar needs. Since it requires a non-discriminatory approach to providing all forms of assistance and services, victim assistance often contributes to addressing some of the rights of other persons with disabilities in the same communities. The Monitor’s reporting has also demonstrated that significant earmarked support to victim assistance is still needed due to the lack of capacity of other so-called frameworks to adequately respond to the needs of cluster mention victims.[32]

In many states, there are inadequate funding and resources for the international organizations, national and international NGOs, and disabled people’s organizations (DPOs) that deliver most direct assistance and services to cluster munition victims. In May 2016, the ICBL-CMC expressed concern that local-level resources available for victim assistance are “reaching the point of catastrophic deficiency in many countries.” The countries noted as most affected include many States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with victims.[33] Additionally, many states have not recovered significantly from the armed conflicts and military interventions that devastated essential infrastructure, including healthcare and rehabilitation. Continuing armed conflict in several countries further hindered the implementation of victim assistance.

Expectations have been placed on the capacity of disability-inclusive development to ensure the sustainability of victim assistance. For example, in 2013, Norway, then a long-time major provider of support to victim assistance implementation through the convention, announced a “prediction that in the coming years we will see a downward trend in funds identified as dedicated to assisting victims…but that more and more states, including donors such as Norway, will strive to ensure that their development cooperation is inclusive of all persons with disabilities.”[34] However, significant reductions to victim assistance support were being felt on the ground in many States Parties with cluster munition victims, while at the same time support to implementation of the rights of persons with disabilities has not been seen to close the gap in the needs of cluster munition victims.[35] The Dubrovnik Action Plan presents an opportunity for States Parties to make progress.

Victim assistance in the Dubrovnik Action Plan

The Dubrovnik Action Plan lays out six very broad objectives to be achieved by the time of the Second Review Conference of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in 2020:

- Improvement in the quality and quantity of assistance for persons with disabilities;

- Strengthened respect for human rights;

- Increased exchange of information on good and cost-effective practices;

- Increased involvement of victims in processes that concern them;

- Increased support for victim assistance programs;[36]

- Increased demonstration of results in Article7 transparency reports.

This summary highlights developments and challenges in States Parties relative to the six objectives of the Dubrovnik Action Plan and their identified actions and results. More details on the implementation of services is available through the Monitor’s "Equal Basis" reporting, which provides information on efforts to fulfill responsibilities in promoting the rights of persons with disabilities—including the survivors of landmines, cluster munitions, and other ERW—in countries that have obligations and commitments to enforce those rights.[37] Data on the provision of victim assistance in States Parties, signatory states, and non-signatories to the Convention on Cluster Munitions is available online in relevant Monitor country profiles.

Improvement in the quality and quantity of assistance

Designated government focal points

According to the Dubrovnik Action Plan, all States Parties with responsibility for cluster munition victims should have designated a focal point within the government to coordinate victim assistance by the end of 2016, in accordance with Article 5 of the convention.[38]

In 2015, only Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Guinea-Bissau, and Sierra Leone did not have, or had not reported, current designated victim assistance focal points. The convention had not yet entered into force for States Parties Colombia and Somalia, but Somalia was lacking overall victim assistance or disability coordination in 2015, while Colombia has both disability rights and victim assistance coordination structures firmly established. All other nine States Parties have reported who are their focal points for victim assistance.

Each designated focal point for victim assistance must have “authority, expertise and adequate resources” according to the Dubrovnik Action Plan. So far, States Parties have not been reporting on all three of these essential elements of the focal point role.

Ongoing data collection

Building national capacity requires an understanding of cluster munition victims’ situations and requirements. Under Article 5, the convention requires that States Parties with victims make “every effort to collect reliable relevant data” and assess the needs of cluster munition victims. The Dubrovnik Action Plan calls for ongoing assessment of the needs of cluster munition victims, while also referring victims to existing services during the data collection process.

Data disaggregated by sex and age was generally available to all relevant stakeholders and its use in program planning was reported for Albania, Afghanistan, BiH, Lao PDR, and Lebanon. Albania had an assessment of socio-economic and medical needs of marginalized ERW victims conducted during 2013–2016. Croatia continued the development of a unified database of all mine/ERW casualties and their families, which required field research on the current situations and needs of victims. Lao PDR continued to maintain the unexploded ordinance (UXO) Survivor Tracking Survey system in 10 provinces. Lebanon also continued to update its victim database that was finalized in 2014. Mozambique reported that survey was needed in order to identify cluster munition victims.

In Afghanistan, the health management information system was not reviewed as planned in 2015 and the few existing disability indicators were insufficient and not very relevant. Methodological gaps in the collection of data occurred in BiH, which has a comprehensive database on mine and ERW casualties, but has repeatedly also reported that further survey was needed to disaggregate data on cluster munition victims. In Iraq, a lack of coordinated data about service provision was the main constraint for service providers to understand needs and for survivors to access services. Lao PDR included basic questions relating to persons with disabilities in its national census in early 2015, but limited training of the census personnel created some confusion among respondents and preliminary results of the census did not mention data on disability.

Coordination, policies, and plans

According to the Dubrovnik Action Plan, coordination of victim assistance activities can be situated within existing coordination systems, including those created for the CRPD, or states can establish a comprehensive coordination mechanism.[39] Existing national policies, plans, and legal frameworks should be utilized; States Parties without a national disability action plan committed, through the Dubrovnik Action Plan, to draft a disability or victim assistance plan before the end of 2018.[40]

National implementation of the CRPD is developing alongside the implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions among most States Parties to both conventions. However, in the reporting period, the structures established under the CRPD often did not have adequate capacity to fulfill the state’s obligations under either convention. Instead, existing victim assistance-specific coordination often remained a viable mechanism for making progress on the objectives relevant to both conventions.

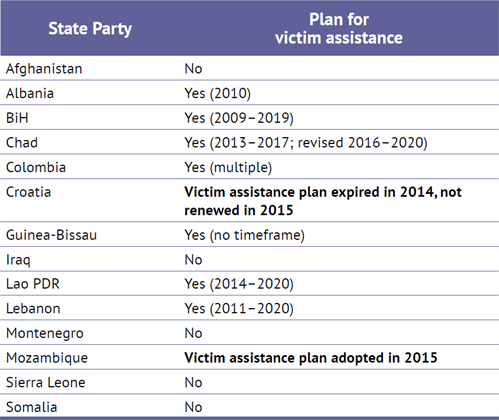

Victim assistance planning in 2015

Note: Bold indicates a change in 2015.

An ongoing challenge in many States Parties where CRPD coordination mechanisms did exist was that the relevant coordination bodies were too weak to coordinate effectively. Therefore, victim assistance coordination could not be effectively integrated into these systems. This has been the case, for instance, in Afghanistan, BiH, and Lao PDR.

Afghanistan also needed to develop, adopt, and implement a national disability plan that includes objectives responding to the needs of survivors and that recognizes its victim assistance obligations and commitments. Croatia’s national plan on victim assistance expired without review in 2014. In Iraq, a gap in developing a national victim assistance strategy was due to the need for improved coordination between the mine action sector ministries and NGOs.

In Lao PDR, plans to hold regular disability sector coordination meetings and link victim assistance coordination with the development of disability strategies were yet to be realized, hampering rapid implementation of recently adopted legislation. A new strategic plan for the UXO Sector developed in 2015 saw a need to improve the coordination on victim assistance between sector stakeholders and the relevant ministries, and to better integrate assistance into broader disability sector programs and workplans.[41]

Mozambique adopted a national victim assistance plan in December 2015, however it lacked the resources needed for implementation. Mozambique identified weak coordination of activities between the relevant sectors and a lack of information about the activities that each sector undertakes as the main challenge to the implementation of victim assistance activities.[42]

Throughout the reporting period, in the majority of States Parties, international organizations and NGOs—both local and international— provided the most direct and measurable assistance to persons with disabilities and war-injured persons, including cluster munition survivors. States Parties sometimes coordinated those activities. Most states themselves also provided some services to survivors through healthcare, rehabilitation, and/or social welfare systems.

Survivor networks and sustainability

In order to strengthen sustainability and the effective delivery of services, States Parties have committed, through the Dubrovnik Action Plan, to enhancing the capacity of organizations representing survivors and persons with disabilities, and national institutions.[43] In anticipation of a drastic and potentially devastating decline in funding for survivor participation broadly, and survivors’ networks in particular, from 2011 the ICBL-CMC began to increase information sharing between survivors’ networks, NGOs, and states. These activities included a series of international interactive side events and discussions held over several years. Importantly, in 2014, a side event considered what would become of survivor participation in disarmament contexts as existing resources were about to decline drastically and generated suggestions for finding new resources for survivor participation. These included collecting private national contributions and uniting with other groups that have more diverse mandates and demands, but similar overall objectives.[44] Increased support directly to survivors’ representative organizations, by states in a position to provide assistance as well as by affected states, is still a massive and increasingly unfulfilled need at the outset of the Dubrovnik Action Plan period, as demonstrated in the following examples:[45]

- Albania: Survivor network continued to exist despite funding shortfalls.

- Afghanistan: Reduced capacity and geographic reach of the survivor network.

- BiH: Survivor network closed in 2016.

- Croatia: Reduced capacity of survivors’ representative organizations; changing focus of survivor networks due to funding constraints.

- Colombia: Increased networking among survivor groups, and peer support training in 2015, but no funding for implementation of services.

- Lao PDR: Survivor group project the Lao Ban Advocates closed in early 2015.

- Lebanon: No survivor network yet established, but recommended by a survey in 2012.

- Mozambique: Reduced capacity of survivor network due to decreased funding.

- Somalia: There were efforts to establish a much-needed survivor network in 2015, but funding for victim assistance is almost non-existent.

Availability and accessibility

At the core of the convention’s victim assistance provisions is the obligation for States Parties responsible for cluster munition victims to adequately provide assistance.[46] Such assistance should be age- and gender-sensitive.[47] States Parties have committed to increasing the availability and accessibility of services in remote and rural areas and to guarantee the implementation of quality services.

Conflict situations significantly hampered effective assistance in States Parties Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia. In Afghanistan, many survivors and conflict-injured persons were beyond the reach of overstretched government services and humanitarian actors.[48] Somalia needed to increase the number of medical staff, adequate health facilities, and services with a particular focus on rural areas.[49] In addition, political instability resulted in decelerated efforts in Guinea-Bissau.

A specific emphasis on increasing the economic inclusion of victims of cluster munitions through training and employment, as well as social protection measures, is found in the Dubrovnik Action Plan. Suggestions include employer incentives or quotas for employment. Oftentimes however, state systems that were intended to implement quotas for the employment of persons with disabilities did not come close to fulfilling their minimum objectives, for example, in Afghanistan, Croatia, Lebanon, and Lao PDR. In 2015, it was also reported that Lebanon had no disability pensions, nor did persons with disabilities receive mobility grants. Civil society in Mozambique reported that the state does not consider a quota system that would ensure inclusion of persons with disabilities in employment because low education levels created a barrier to job entry.[50]

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with victims are legally bound to implement adequate victim assistance in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law.[51] Applicable international human rights law includes the CRPD, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. For example, the Convention on Cluster Munitions has no definition, or measure of, what might constitute “adequate” assistance. However, applicable international law provides more specific classifications, and includes such requirements as achieving the “highest attainable standard” of physical and mental health.[52]

Instruments of international humanitarian law pertinent to the implementation of victim assistanceinclude the Mine Ban Treaty, the Convention on Conventional Weapons’ Protocol V on Explosive Remnants of War, and the Geneva Conventions. The 1951 Refugee Convention is also relevant.

All but two of the States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with cluster munition victims (Lao PDR and Lebanon) are also party to the Mine Ban Treaty and, as such, have made victim assistance commitments through the Mine Ban Treaty’s action plans. The Geneva Conventions and their additional protocols, as well as customary law may also be relevant, particularly in the cases of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia, which are among the States Parties where conflict is ongoing.

States Parties’ understanding of their international humanitarian and human rights law requirements has mostly focused on a rights-based approach with particular emphasis on integrating efforts to fulfill those obligations with the implementation of the CRPD, and engaging national structures developed for coordination of the CRPD, where they exist.

One State Party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with cluster munition victims is not a signatory to the CRPD (Somalia). Two are signatories to the CRPD (Lebanon and Chad) and all others are States Parties. In order for improvements as countries set out to implement the Dubrovnik Action Plan, concerted international efforts are needed to ensure support with actions, far beyond reiterations of limited examples of “good practices” and “lessons learned.” Issues in need of attention due to the slow pace of the enforcement of the rights and meeting of the needs of persons with disabilities in States Parties with cluster munition victims include:

- Afghanistan: The law on the rights of persons with disabilities included discriminatory sections and was being reviewed. Local NGOs and DPOs also reported that the implementation of the CRPD received little attention. The committee established to review the legislation was yet to make suggested amendments.

- BiH: Persons with disabilities are not adequately protected by anti-discrimination regulations and, as of 2015, the existing anti-discrimination law still had not been amended to include disability as grounds for discrimination. BiH needed to address discrimination based on the category of disability and improve the quality and sustainability of services for survivors and other persons with disabilities.

- Chad: Persons with disabilities including survivors’ representative organizations continued to hold regular public protests calling on the government to implement disability rights legislation, create accessible environments, and ratify the CRPD. Chad needed to enhance victim assistance coordination and align with disability rights coordination; plan and undertake survivor identification and needs assessment; increase services in all areas of victim assistance, particularly employment; and improve professional capacity in the physical rehabilitation sector.

- Croatia: The absence of a broad service providers’ network forced DPOs to assume a networking role, at the expense of their human rights advocacy role. NGOs suggested that Croatia begin a comprehensive review of existing legislation, align legislation with the CRPD in accordance with the human rights model of disability, and provide funding to enable DPOs to fulfill their role in advocacy and decision-making processes.

- Guinea-Bissau: Persons with disabilities were among the most disadvantaged in all regards, experiencing neglect within their communities and throughout the health, education, and social protection systems. Guinea-Bissau was yet to adopt sectoral plans for the promotion of the rights of persons with disabilities.

- Iraq: Persons with disabilities continued to suffer from a lack of institutional infrastructure, schools and means of education, and rehabilitation programs, as well as access to health and employment opportunities. There was a “failure to allocate a special budget to help cover those needs.”[53] Iraq was yet to improve the planning and coordination of victim assistance and disability issues throughout the country and increase the participation of survivors and their representative organizations.

- Lao PDR: noted that it “has a long way to go to fully achieve the victim assistance goals within the broader disability and development frameworks.”[54] No change was reported by Lao PDR in its efforts to raise awareness of the rights of cluster munitions victims and persons with other disabilities since 2010.[55]

- Lebanon: Persons with disabilities faced challenges in gaining access to services, isolation, and stigma. Lebanon still needed to enforce law 220/2002 on persons with disabilities. It was reported that Lebanon lacked a budget for its implementation and a national disability policy. Insufficient coordination between relevant ministries wasted the opportunities for implementation of existing legislation.[56]

- Mozambique: Civil society organizations reported that in contrast to the past, “the political environment is…unfavorable and not taking real steps to improve the implementation of the [CRPD].” It was further reported that the “political system also excludes the disabled person, not involving them in decision-making process.”[57]

- Somalia: In October 2015, Somalia’s Federal Cabinet unanimously approved the Persons with Disabilities bill, which is intended to eliminate all forms of discrimination against persons with disabilities and improve the living standards of persons with disabilities.[58] Persons with disabilities are subject to discrimination, exploitation, and abuse by both public and private actors, without means or mechanisms for addressing violations of their rights.[59] Somalia was yet to ratify the CRPD and tackle unemployment among persons with disabilities through a national plan for promoting job creation as recommended by rights groups.

Non-discrimination

States Parties must not discriminate against or among cluster munition victims, or between cluster munition victims and those who have injuries or disabilities from other causes, according to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[60] From 2015, States Parties have committed to monitor the implementation of victim assistance and ensure that the relevant frameworks do not discriminate, while also guaranteeing that cluster munition victims can access specialized services as needed.[61]

In most countries—not only States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions—war veterans with disabilities are assigned a privileged status above that of civilian war survivors and other persons with disabilities, particularly with respect to financial allowances and other state benefits. States Parties need to be mindful of the requirement not to affect existing rights, as set out in Article 4.4 of the CRPD.[62]

Exchange of information on good and cost-effective practices

The Convention on Cluster Munitions coordinators on victim assistance and coordinators on cooperation and assistance, with technical support from Handicap International, began preparation for a guidance document “by states for states” on an integrated approach to victim assistance to be issued during 2016.[63] In this context, an integrated approach can be understood to mean supporting victim assistance commitments and obligations through international cooperation and national coordination with two core complimentary elements:

- First, that international support to survivors continues to increase benefits to other persons with disabilities; and

- Second, that other international assistance, such as that provided through funding to protracted crisis development initiatives, human rights, the rights of persons with disabilities and inclusive development, poverty reduction, and humanitarian response, should also reach, amongst the beneficiaries, survivors and others in their communities.[64]

In May 2016, a workshop held in Geneva provided an opportunity for Convention on Cluster Munitions and Mine Ban Treaty States Parties,[65] and other organizations,[66] to share views on national examples of good practices and challenges in implementing an integrated approach to victim assistance. The guidance document is to include the combined input from the workshop and responses to questionnaires.

Prior to its ratification, Colombia had already started sharing good practices on victim assistance with States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions at the intersessional meetings of the convention in April 2014 and through the Bridges Between Worlds conference hosted by Colombia in Bogota in the same month.[67]

States Parties have obligations to “closely consult with and actively involve cluster munition victims and their representative organizations.”[68] The states have committed to actively include cluster munition victims and their representative organizations in policy-making and decision-making, so that their participation is made sustainable and meaningful.[69] In most States Parties, survivors were engaged in, or invited to attend, relevant activities. Exceptions included Guinea-Bissau, Montenegro, Sierra Leone, and Somalia where no survivor involvement in victim assistance activities was identified. However, DPOs were active in all four countries.

Many States Parties regularly report that survivors are included in decision-making activities. However, reporting from service providers, survivors’ organizations, and affected communities most often presents a more nuanced view. Following are examples of participation and variance in practice in 2015:

- Albania: Survivors participated in victim assistance planning and implementation of services, including the survivor survey, through participation in the national survivor representative organization.

- Afghanistan: Persons with disabilities and their representative organizations were included in decision-making and participated in the various coordination bodies. However, it was sometimes reported that their views were not fully taken into account.

- Chad: Participation was not reported.

- Colombia: Survivors participated in some coordination meetings and at national and departmental Victim’s Participation Roundtables (VPRs).

- Croatia: Survivors and/or their representative organizations equally participated in the two meetings of the national coordinating body in 2015 and were involved in consultations through networking of their representative organizations.

- Iraq: Survivors participated in victim assistance discussions and meetings through the Iraqi Alliance for Disability.

- Lao PDR: Handicap International’s Lao Ban Advocates project, which had supported survivor participation in victim assistance coordination since 2010,ended inMarch 2015. In 2015, Lao PDR reported that the government worked closely with representatives of several DPOs.

- Lebanon: The national steering committee on victim assistance includes a survivor and members of DPOs.

- Mozambique: Mine/ERW survivors were represented in the coordination of disability and victim assistance in two meetings of the national disability coordination body. They engaged in the monitoring of disability rights policy through a national umbrella organization of persons with disabilities.

By the end of the Dubrovnik Action Plan period, States Parties will also need to demonstrate how they have included cluster munitions victims and representatives of DPOs as relevant experts to be part of their delegations in all convention-related activities.[70] At the First Review Conference survivor and victim participation was organized by civil society; the CMC and its members.

Support for victim assistance programs

The Convention on Cluster Munitions holds that States Parties in a position to do so should support the implementation of the convention’s victim assistance obligations. International cooperation and assistance should be provided by States Parties for the implementation of the victim assistance by other States Parties to the convention. These may be made bilaterally or through other bodies and organizations.[71] Large differences between the needs in States Parties and the resources made available through international cooperation continued to obstruct progress in victim assistance in 2015. Below are some of the situations reported for States Parties in 2015:

- BiH: A lack of resources continued to erode victim assistance efforts as donor funding declined. After more than 18 years of continuous operation, the NGO Landmine Survivors Initiatives (once a branch office of the US-based NGO Landmine Survivors Network/Survivor Corps) closed down permanently.[72]

- Colombia: International cooperation continued to decrease, leaving large gaps in the support for survivors previously provided by national networks and through local organizations and international NGOs. This funding is crucial for connecting survivors with existing services, especially peer support networks for survivors and persons with disabilities, which cannot be funded through the national health insurance system.

- Croatia: NGOs found that there had been an overall decrease in the number of people that they could assist “due to the omnipresent lack of financial resources.”[73] The government reduced overall funding for programs for persons with disabilities as part of budget cuts.[74] Austerity measures reduced the previously achieved standard supply of orthopedic devices.[75]

- Iraq: The country suffers from a financial crisis while the focus of donors and international NGOs is on the massive needs of internally displaced persons. This has diminished financial support to victim assistance and minimized the scale of service provisions to survivors across the country.[76]

- Lao PDR: There were little available resources and few donors made victim assistance a priority.[77] The budget allocated to victim assistance is very limited, and as a result Lao PDR cannot pursue its strategic plan for the Dubrovnik Action Plan period through 2020.[78]

- Lebanon: The funding situation had improved since a severe decline in 2013. However, the current level of support was insufficient to serve the needs of victims.[79]

- Mozambique: Insufficient financial and qualified human resources was one of the main challenges to implementation of victim assistance activities.[80] Handicap International noted a lack of success in its exceptional efforts to raise funds, and found that donors seemed to lose interest in victim assistance as a result of the completion of landmine clearance in Mozambique.[81]

Demonstration of results in Article 7 transparency reports

Under Article 7 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties are required to report on the status and progress of implementation of all victim assistance obligations. This reporting requirement is both a legal obligation and an opportunity. In the Dubrovnik Action Plan, States Parties with responsibility for cluster munition victims have committed to making the best use of Article 7 reports. States can share progress providing positive examples and strengthening the norm of victim assistance. They can also clearly present their challenges and how technical and financial support from the international community would help.

In 2016, Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mozambique reported in detail on victim assistance efforts. However, for the most part, reporting did not present what constituted progress made during the previous calendar year. There was often little specific reference to plans, actions, or adaptions made to other frameworks for the implementation of victim assistance.[82] Chad presented minimal reporting. Montenegro had not submitted its report for calendar year 2015, but has previously reported on victim assistance focal points and legislation. Guinea-Bissau has never submitted an Article 7 report for the Convention on Cluster Munitions and Sierra Leone did not include the form on victim assistance in its initial Article 7 report. Colombia and Somalia are due to submit reports later in 2016 and will have the opportunity to highlight their victim assistance needs, plans, and along with their fellow States Parties, progress on implementing the Dubrovnik Action Plan.

[1] Cluster munition casualties include persons killed and injured, and those persons for whom it was not reported if they survived.

[2] Cluster munition remnants include abandoned cluster munitions, unexploded submunitions, and unexploded bomblets, as well as failed cluster munitions. Unexploded submunitions are “explosive submunitions” that have been dispersed or released from a cluster munition but failed to explode as intended. Unexploded bomblets are similar to unexploded submunitions but refer to “explosive bomblets,” which have been dispersed or released from an affixed aircraft dispenser and failed to explode as intended. Abandoned cluster munitions are unused explosive submunitions or whole cluster munitions that have been left behind or dumped and are no longer under the control of the party that left them behind or dumped them. See, Convention on Cluster Munitions, Art. 2 (5), (6), (7), and (15).

[3] See also, Handicap International (HI), Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels: HI, May 2007), bit.ly/MonitorHICircleofImpact2007. “A conservative estimate indicates that there are at least 55,000 cluster submunitions casualties but this figure could be as high as 100,000 cluster submunitions casualties.”

[4] The table notes states and areas where casualties occurred. No precise number, or estimate, of casualties is known for Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, or Somalia. There are known to be other states with cluster munition victims, including casualties who were injured and the families of casualties killed on the territory of other states.

[5] The Monitor collects data from an array of sources, including national reports, mine action centers, mine clearance operators, victim assistance service providers, as well as from a range of national and international media. Global cluster munition casualty data used by the Monitor includes the global casualty data collected by HI in 2006 and 2007. For the 13,306 cluster munition casualties reported for all time in 2007, see, HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels: HI, May 2007), bit.ly/MonitorHICircleofImpact2007.

[6] In total, 2,635 cluster munition casualties were recorded in the period 2010–2015 by the Monitor.

[7] From 2010–2015 there were 1,023 civilian casualties, 19 clearance personnel casualties, and 49 military casualties, of 706 casualties where the civilian status was reported.

[8] HI found that 98% of casualties were civilian by projecting the percentage of casualties for which civilian statues was known to those with unknown civilian status. Of the number of known casualties, the percentage of civilians was some 94%. Data used by the Monitor includes global casualty data collected by HI in 2006 and 2007. The addition of new data sources over time did not significantly change the percentage of civilian casualties. See, HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels: HI, May 2007), bit.ly/MonitorHICircleofImpact2007.

[9] There were 223 child casualties, 300 adult casualties, and 116 of unknown age.

[10] For another 1,324 casualties documented it was not specified how many were due to strikes.

[11] It is possible that cluster munition casualties have occurred but gone unrecorded in other countries where cluster munitions were used, abandoned, or stored in the past—such as States Parties Mauritania and Zambia and non-signatories Azerbaijan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Zimbabwe. Better identification and disaggregation of cluster munition casualties are needed in most cluster munition-affected states and areas. States Parties Mauritania and Zambia have both reported that survey is required to identify whether they have cluster munition victims on their territories. They have not yet been included in list of states with cluster munition casualties. There is also a firsthand historical account of civilian casualties from an incident with an unexploded submunition at a weapons testing range in Zimbabwe, a non-signatory state (in the time of the former Rhodesia). For the first time in 2015, Chad—a State Party reported to have cluster munition casualties earlier, but lacking disaggregated casualty data—recorded a specific unexploded submunition incident causing casualties. As reported by Angola, a national victim survey identified at least 354 cluster munition survivors in one province of the country. However, since Cluster Munition Monitor 2015 was published, newly available information has indicated uncertainty around this finding, both whether the casualties were caused by cluster munitions and the means by which they were identified. Those reported cluster munition casualties in Angola have not been confirmed by two surveys conducted in the past year, including a specific desk-based casualty survey. The casualties reported for Angola remain in the Cluster Munition Monitor global casualty total, pending further clarification.

[12] For 2014, 10 countries and one other area had 445 reported cluster munition casualties. See, previous Cluster Munition Monitor reports for other annual casualty totals.

[13] Sex was not recorded for 212 of 388 civilian casualties in 2015.

[14] Cluster munitions caused 13 of 17 recorded mine/ERW casualties in 2015, or 76% of the total.

[15] For Syria, 248 cluster munition casualties were reported in 2015; 383 in 2014; 1,001 in 2013; and at least 583 for 2012. The extreme difficulties faced in collecting data continued to intensify, which likely influenced, or resulted in, the decline in the annual reported cluster munition casualty numbers.

[16] Of the total cluster munition casualties in Yemen in 2015, 93 were civilian and the remaining 11 casualties were security forces.

[17] Casualty data sent by email from Fadel Abdul Ghani, Director, SNHR, 8 June 2016; and SNHR, “Russian Forces are Pouring Cluster Munition [sic] over Syria No less than 54 Russian Cluster Attacks Recorded before the Cessation of Hostilities Statement,” 22 July 2016, bit.ly/SN4HR22July2016. In some cases, the number of casualties in Human Rights Watch (HRW) reporting differs from SNHR reporting. See, HRW, “Russia/Syria: Extensive Recent Use of Cluster Munitions,” 20 December 2015, www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/20/russia/syria-extensive-recent-use-cluster-munitions.

[18] HRW, “Russia/Syria: Extensive Recent Use of Cluster Munitions,” 20 December 2015, www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/20/russia/syria-extensive-recent-use-cluster-munitions.

[19] HRW, “Yemen: Cluster Munitions Wounding Civilians,” 14 February 2016, www.hrw.org/news/2016/02/14/yemen-cluster-munitions-wounding-civilians.

[20] HRW, “Ukraine: More Civilians Killed in Cluster Munition Attacks,” 19 March 2015, www.hrw.org/news/2015/03/19/ukraine-more-civilians-killed-cluster-munition-attacks.

[21] HRW, “A Dying Practice: Use of Cluster Munitions by Russia and Georgia in August 2008,” 14 April 2009, www.hrw.org/report/2009/04/14/dying-practice/use-cluster-munitions-russia-and-georgia-august-2008.

[22] HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels: HI, May 2007), p. 85.

[23] Three schools were also heavily damaged and another contaminated, but there were no casualties as students were not in school at the time. Norwegian People’s Aid, Yellow Killers, the Impact of Cluster Munitions in Serbia and Montenegro (NPA: Belgrade, January 2007), pp. 25 and 55.

[24] HI, Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities (Brussels: HI, May 2007), p. 52.

[25] Ibid., p. 61.

[26] These activities include medical care, rehabilitation, and psychological support, as well as provision for their social and economic inclusion.

[27] Cluster munition victims include survivors (people who were injured by cluster munitions or their explosive remnants and lived), other persons directly impacted by cluster munitions, as well as their affectedfamilies and communities. Most cluster munition survivors are also persons with disabilities. The term “cluster munition casualties” is used to refer both to people killed and people injured as a result of cluster munition use or by cluster munition remnants.

[28] See, Article 5 and Article 7.k. of the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

[29] Including medical, rehabilitative, psychological, or socio-economic needs. Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.2.e. This is also relevant to international humanitarian law, including Additional Protocol II of the Geneva conventions, in regard to wounded military personnel and direct participants in hostilities: “There shall be no distinction among them founded on any grounds other than medical ones.” Article 7.2., Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II), 8 June 1977, bit.ly/GenevaProtocolII.

[30] See, Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.2.e; CRPD, Article 3.b; and CRPD, Article 4.1.

[31] The preamble states: “Bearing in mind the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which, inter alia, requires that States Parties to that Convention undertake to ensure and promote the full realisation of all human rights and fundamental freedoms of all persons with disabilities without discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability.”

[32] ICBL-CMC, “Frameworks for Victim Assistance: Monitor key findings and observations,” December 2013, http://the-monitor.org/media/131747/Frameworks_VA-December-2013.pdf.

[33] ICBL-CMC, “Statement on Victim Assistance,” Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, 19 May 2016, www.icbl.org/media/2333176/icbl-statement-on-victim-assistance.pdf.

[34] Presentation of Norway, “Convention on Cluster Munitions Technical Workshop on Cooperation and Assistance,” 15 April 2015, www.clusterconvention.org/files/2013/04/II-Norway.pdf.

[35] In the case of Norway, in November 2015, 160 Norwegian civil society organizations protested cuts to the aid budget that would negatively affect inclusive development and the rights of persons with disabilities.

[36] Including through “traditional mechanisms, and south-south, regional and triangular cooperation and in linking national focal points and centres.”

[37] See, ICBL-CMC, “Equal Basis 2015: Inclusion and Rights in 33 Countries,” December 2015, pp. 5–6, bit.ly/EqualBasis2015; and ICBL-CMC, “Equal Basis 2014: Access and Rights in 33 Countries,” December 2014, bit.ly/MonitorEqualBasis2014.

[38] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.2g. Note: Under Action #4.1 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions’ 2011–2015 Vientiane Action Plan, States Parties committed to designating a government focal pointfor victim assistance within six months of the convention’s entry into force for each State Party.

[39] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1 (c). A comprehensive coordination mechanism actively involves cluster munition victims and their representative organizations, as well as relevant health, rehabilitation, psychological, psychosocial services, education, employment, gender, and disability rights experts.

[40] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1 (c).

[41] National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action Sector in Lao PDR, HRTM 2015: UXO Sector Working Group Progress Report, Vientiane, 15 November 2015.

[42] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for the calendar year 2015), Form H.

[43] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1 (a).

[44] ICBL Report on Activities, Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference, undated, p. 15.

[45] See individual country profiles available on the Monitor website for details, www.the-monitor.org/cp.

[46] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 5.1, which applies with respect to cluster munition victims in areas under the State Party’s jurisdiction or control.

[47] Children require specific and more frequent assistance than adults. Women and girls often need specific services depending on their personal and cultural circumstances. Women face multiple forms of discrimination, as survivors themselves or as those who survive the loss of family members, often the husband and head of household.

[48] ICRC, “Annual Report 2015,” Geneva, 2016, p. 334.

[49] Somalia Civil Society Organizations Universal Periodic Review Report May 2015, Somalia Civil Society Organizations – Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) Universal Periodic Review (UPR) submissions.

[50] UPR Mechanism of the UN Human Rights Council Shadow Report – Mozambican civil society (Cycle 2012–2015), bit.ly/UPRMozambiqueShadow2012-2015.

[51] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.1.

[52] See, for example, CRPD, “Article 25 – Health,” www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CRPD/Pages/ConventionRightsPersonsWithDisabilities.aspx - 25; and Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 12),” 11 August 2000, www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/Health/GC14.pdf.

[53] Human Rights Council, “Summary Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review: Twentieth session,” A/HRC/WG.6/20/IRQ/3, 27 October–7 November 2014, p. 65.

[54] National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action Sector in Lao PDR, "HRTM 2015: UXO Sector Working Group Progress Report," Vientiane, 15 November 2015.

[55] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2015), Form H.

[56] “A common presentation by several PWD Associations, to the ‘High Commissioner of Human Rights’ on the occasion of the 10th session of the ‘Universal Periodic Review 2015,’” bit.ly/UPRLebanon2015.

[57] Universal Periodic Review Mechanism of the UN Human Rights Council Shadow Report – Mozambican civil society (Cycle 2012–2015), bit.ly/UPRMozambiqueShadow2012-2015.

[58] Abdirahman A., “Somalia Cabinet Approves Persons with Disabilities Bill,” Horseed Media, 9 October 2015, https://horseedmedia.net/2015/10/09/somalia-cabinet-approves-persons-with-disabilities-bill.

[59] Summary prepared by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in accordance with paragraph 15 (c) of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1 and paragraph 5 of the annex to Council resolution 16/21, (A/HRC/WG.6/23/SOM/3) 6 November 2015.

[62] “Nothing in the present Convention shall affect any provisions which are more conducive to the realization of the rights of persons with disabilities and which may be contained in the law of a State Party or international law in force for that State.” CRPD, Article 4.4.

[63] Convention on Cluster Munitions Implementation Support Unit (ISU), “Workshop on an Integrated Approach to Victim Assistance,” (including workshop documents) 27 May 2016, www.clusterconvention.org/2016/05/27/workshop-on-an-integrated-approach-to-victim-assistance.

[64] See, ICBL-CMC, “Equal Basis 2015: Inclusion and Rights in 33 Countries,” December 2015, pp. 5-6, www.the-monitor.org/media/2155496/Equal-Basis-2015.pdf. The integrated approach through relevant frameworks and domains can be differentiated from a comprehensive “integrated approach” to victim assistance that includes the key components, or “pillars,” of assistance that was frequently used terminology in the Mine Ban Treaty. Regarding an “integrated approach” to victim assistance as comprehensive assistance through coordinated implementation of its key components data collection, emergency and ongoing medical care, physical rehabilitation, psychological support and social reintegration (inclusion), economic reintegration (inclusion), and laws and policies, see, ICBL, “Guiding Principles on Victim Assistance,” 2007, www.icbl.org/media/919871/VA-Guiding-Principles.pdf; and “Chapter 5 – A Holistic and Integrated Approach to Addressing the Rights and Needs of Victims and Survivors: Good Practice,” in Mine Ban Treaty ISU, Assisting Landmine and other ERW Survivors in the Context of Disarmament, Disability and Development (Geneva, 2011), pp. 75–99, http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Full_Report_1398.pdf.

[65] Albania, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Cambodia, Canada, Chile, Croatia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Italy, Japan, Lao PDR, Mozambique, Netherlands, Norway, Peru, Spain, Switzerland, Tajikistan, Thailand, as well as the United States, which is not party to either convention, but is party to CCW Protocol V.

[66] Non-state representatives that attended the workshop were from the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, the ICBL-CMC, the Gender and Mine Action Program, the International Disability Alliance, the Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities-Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, survivors from El Salvador and Uganda, an independent expert on disability and victim assistance from Australia, and the UN Mine Action Service.

[67] Statement of Colombia, Convention on Cluster Munition Working Group on Victim Assistance, Geneva, 9 April 2014.

[68] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.2.f.

[69] Dubrovnik Action Plan 4.2, "Increase the involvement of victims." items a and b.

[70] Dubrovnik Action Plan 4.2, (b) “Include relevant experts to be part of their delegations in all convention related activities (including cluster munitions victims, and representatives of disabled person’s organizations).”

[71] Such assistance may be provided, inter alia, through NGOs; the UN system; international, regional, or national organizations or institutions; the ICRC; national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and their International Federation; or on a bilateral basis. Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 6, and Article 6.7.

[72] Landmine Survivors Initiatives, “The closure of Association ‘Landmine Survivors Initiatives’,” 31 May 2016, bit.ly/LSIClosure; and see also, Amir Mujanovic, “Providing Integrated Peer-support Assistance to Landmine Survivors,” The Journal of ERW and Mine Action, Issue 19.3, December 2015, bit.ly/MujanovicPeerSupport.

[73] Statement by Croatia, CCW Protocol V Meeting of Experts, Geneva, 7 April 2015.

[74] US Department of State, “2015 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Croatia,” Washington, DC, 13 April 2016, bit.ly/USHRReportCroatia2015.

[75] Ombudsman of the Republic of Croatia, “Universal Periodic Review On Human Rights In The Republic Of Croatia - Nhri Report, 2nd cycle,” September 2014.

[76] Response to Monitor questionnaire from Ahmed Al Zubaidi, Iraqi Health and Social Care Organization (IHSCO), 27 July 2016.

[77] Victim assistance statements of Lao PDR, Convention on Cluster Munitions First Review Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 7–11 September 2015.

[78] UNDP in Lao PDR, “UXO Sector Working Group approves new strategy,” 16 November 2015, bit.ly/UNDP2015UXOStrategy.

[79] Emails from Brig. Gen. Nassif, Lebanon Mine Action Center, 13 May and 9 June 2015.

[80] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for the calendar year 2015), Form H.

[81] Notes from side event, Mine Ban Treaty Fourteenth Meeting of States Parties, December 2015.

[82] States Parties committed to “Ensure that existing national policies, plans and legal frameworks related to people with similar needs, such as disability and poverty reduction frameworks, address the needs and human rights of cluster munition victims, or adapt such plans accordingly.” Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1 (c).