Landmine Monitor 2017

A Global Overview of Banning Antipersonnel Mines

Banning Antipersonnel Mines

2017 marks 20 years since the Mine Ban Treaty was adopted in Oslo on 18 September 1997 and opened for signature in Ottawa less than three months later. In between those key milestones, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) and its then coordinator Jody Williams were awarded the 1997 Nobel Peace Prize.

After two decades, the Mine Ban Treaty has matured into an emerging international norm with impressive universality. A total of 162 States Parties are implementing the treaty’s provisions prohibiting antipersonnel landmines and requiring victim assistance, clearance of mined areas within 10 years, and destruction of stockpiled mines within four years. Most of the 35 countries that remain outside of the treaty are nonetheless abiding by its key provisions. The stigma against landmines remains strong.

But not all States Parties are on track to fulfill their Mine Ban Treaty obligations in a timely fashion. Missed stockpile destruction deadlines, missed deadlines for extensions of mine clearance deadlines, and repeated requests for extensions of mine clearance deadlines raise compliance concerns.

Additionally, new landmine use, particularly the widespread use of so-called improvised mines by non-state armed groups (NSAGs), is resulting in a significant increase in casualties and threatening to undermine the progress toward the long-held goal of a landmine-free world. While mine use by government forces remains a rare phenomenon, the government forces of states not party Myanmar and Syria used antipersonnel landmines in 2016 and 2017.

NSAGs used antipersonnel landmines in at least nine countries, including Ukraine and Yemen. The extensive use of improvised mines by the forces of the Islamic State (IS) has created new casualties and contaminated land.

These improvised landmines are often referred to as improvised explosive devices (IEDs) or booby-traps. However, most are exploded by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person and therefore meet the definition of an antipersonnel mine contained in the Mine Ban Treaty and are prohibited regardless of whether they were fabricated in a factory or elsewhere.

Some states have chosen not to use the humanitarian disarmament framework provided by the Mine Ban Treaty to address what they call the “IED threat” and instead pursue non-binding measures through the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW). Such an approach is short-sighted, misguided, and costly. It may appeal to states that have not joined the Mine Ban Treaty such as China, Russia, and the United States (US), but it ignores a key opportunity to remind NSAGs of the stigma that the Mine Ban Treaty has created against any use of antipersonnel mines, by any actor, under any circumstances. In November 2016, the ICBL called on Mine Ban Treaty States Parties to condemn any new use of improvised antipersonnel mines and seek out new ways to stigmatize and stop this use.[1] As Mine Ban Treaty president Austria affirmed in October 2017, the Mine Ban Treaty clearly encompasses all antipersonnel mines, regardless of whether they are improvised or factory-produced, and irrespective of who used them.[2]

Like-minded governments, UN agencies, and international organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Geneva International Center for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) continue to work together with the ICBL to address Mine Ban Treaty compliance challenges in a cooperative manner. The unity demonstrated by that community over the past two decades remains strong and focused on the Mine Ban Treaty’s ultimate objective of putting an end to the suffering and casualties caused by antipersonnel mines.

Use of antipersonnel landmines

In this reporting period—October 2016 through October 2017—Landmine Monitor has confirmed new use of antipersonnel mines by the government forces of Myanmar and Syria, neither of which are party to the Mine Ban Treaty. There have been no allegations of the use of antipersonnel mines by States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty in the reporting period.

Landmine Monitor recorded new use of antipersonnel mines by NSAGs in Afghanistan, India, Iraq, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen.[3]

There was no new use of antipersonnel mines in Colombia for the first time since the Monitor began publishing in 1999. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo, FARC) and the Colombian government signed an agreement in November 2016 to end the armed conflict. This resulted in a halt to the FARCs widespread use of improvised antipersonnel landmines and the surrender and destruction of its stockpile (see below). On 1 October 2017, a ceasefire agreement between the government of Colombia and the National Liberation Army (Unión Camilista-Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN) took effect.[4]

The use of landmines, improvised landmines, and other types of IEDs by Boko Haram militants in Nigeria has become more acute. Nigeria has not provided an Article 7 transparency report since 2012; the required annual report should update States Parties regarding new mine use within the country. Nigeria also did not provide updated information at the Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties in November–December 2016.

Landmine Monitor has been unable to confirm allegations of new antipersonnel mine use by NSAGs in Cameroon, Chad, Iran, Libya, Mali, Niger, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia.

Use by and in states not party

Myanmar

Since the publication of its first annual report in 1999, Landmine Monitor has consistently documented the use of antipersonnel mines by government forces and NSAGs in Myanmar. In September 2016, Deputy Minister of Defense Major General Myint Nwe informed parliament that the army continues to use landmines in internal armed conflict. He stated that government forces, known as Tatmadaw, used landmines to protect state-owned factories, bridges, and power towers, and its outposts in military operations. The deputy minister stated that landmines were removed when the military abandoned outposts, or warning signs were placed where landmines were planted, and soldiers were not present.[5] In June 2017, a Ministry of Defense official stated to the Landmine Monitor that the military does not use landmines near highly populated areas.[6]

According to eyewitness accounts, photographic evidence, and multiple reports, antipersonnel mines have been laid between Myanmar’s two major land crossings with Bangladesh, resulting in casualties among Rohingya refugees fleeing government attacks on their homes. The mine use began in late August 2017, when Myanmar government forces began operations against the Rohingya population, causing the flight of more than 600,000 people to neighboring Bangladesh. It is unclear if this mine use has continued as parts of the border area remain inaccessible.

Displaced Rohingya civilians who crossed into Bangladesh witnessed a military truck arrive on the Myanmar side of the border from which they witnessed Myanmar government soldiers unloading three crates on 28 August.[7] They said the soldiers removed antipersonnel landmines from the crates and placed them in the ground, later returning at night to place more mines. On 5 September, Reuters reported that two Bangladeshi sources witnessed three to four groups working near the border’s barbed wire fence “putting something into the ground” that Reuters subsequently determined to be landmines.[8] Also on 5 September, two children from Myanmar who had fled to Bangladesh were injured after reportedly attempting to destroy landmines they discovered on the border.[9]

Amnesty International reported on 9 September that it had spoken to several eyewitnesses who said they saw Myanmar military forces, including military personnel and the Border Guard Police, using antipersonnel mines near Myanmar’s border with Bangladesh.[10] Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported on 23 September that military personnel had planted antipersonnel mines in northern Rakhine state prior to their attacks on predominantly Rohingya villages.[11] Rohingya refugees from Buthidaung and Rathedaung townships in Rakhine state told HRW that they saw the Burmese military laying antipersonnel mines on roads as the military entered and attacked villagers. Two other Rohingya refugees told HRW that men in apparent Myanmar military uniforms were seen in the northern part of Taung Pyo Let Yar performing some activity on the ground. One said that on 4 September he observed several soldiers from a patrol stop at least twice, kneel down on the ground, dig into the ground with a knife, and place a dark item into the earth. Both Amnesty International and HRW reviewed photos of the mines used along the Bangladesh border that clearly show PMN-1 type antipersonnel mines lying in the ground. Neither organization could determine if these mines were originally manufactured in the Soviet Union or copies of that mine made by Myanmar, named MM-2, or by China, named Type 58.

NSAGs in Myanmar also used antipersonnel mines in the reporting period. In June 2017, a local administrator in Tarlaw, Myitkyina township, Kachin state blamed the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) for landmines that had caused civilian casualties near the town as well as loss of livestock.[12] In January 2017, the Democratic Karen Benevolence Army (DKBA) faction acknowledged that it had laid mines that injured two Myanmar Army soldiers in the Mae Tha Wor area of Hlaingbwe township in Kayin state.[13] In November 2016, two members of the KIA were apprehended by government forces, and confessed to laying landmines near Labunkadaung village in Hpakan township. When the army took the KIA soldiers to the spot to defuse the mines they had laid, one exploded, killing both of them.[14] In September and October 2016, mines were laid during armed conflict in Hlaingbwe township by a faction of the Democratic Karen Benevolence Army (DKBA).[15]

Syria

In late 2011, the first reports emerged of Syrian government use of antipersonnel mines in the country’s border areas.[16] A Syrian official acknowledged the government had “undertaken many measures to control the borders, including planting mines.”[17]

In January 2016, Doctors Without Borders (Medecins sans Frontieres, MSF) reported that Syrian government forces laid landmines around the town of Madaya in Rif Dimashq governorate, 10 kilometers from the Lebanon border. According to MSF, civilians trying to flee the city have been killed and injured by “bullets and landmines.”[18] In October 2016, residents of Madaya claimed that the Lebanese armed group Hezbollah, operating together with Syrian government forces, laid antipersonnel mines around the town. A medical group and a media organization reported that “landmines” have been laid around the edge of the town.[19]

The non-state armed group Islamic State (IS) used landmines extensively in 2017, with the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) reporting 12 casualties in Raqqa governorate in just August and September, from incidents in Kasrat Srour,[20] Raqqa city,[21] and Hneida.[22] Syria’s state-run news agency reported in October that a photographer with Syrian state TV was killed in the central Homs province when a landmine left behind by IS militants exploded.[23]

As IS retreated from former strongholds, it left behind improvised landmines and booby-traps in a last-ditch effort to kill civilians and government forces. The SNHR reported several incidents from mines that IS fighters likely laid, as the group controlled the territory for prolonged periods of time. For example, in Aleppo governate alone, SNHR reported civilian casualties in August, September, and October 2016 from landmines that IS apparently laid in the villages of Najm,[24] Abu Qalqal,[25] Al Humar,[26] and Al Dadat.[27] In October 2017, a British citizen fighting with the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) was killed while clearing landmines in the abandoned Raqqa city.[28] Between September 2015 and January 2017, Mines Advisory Group (MAG) cleared 7,500 improvised mines and other improvised devices from Iraq and Syria.[29]

During a five-day investigation in Manbij in early October 2016, HRW collected the names of 69 civilians, including 19 children, killed by improvised mines, including booby-traps, laid by IS in schools, homes, and on roads during and after the fighting for control for the city, involving IS and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—a coalition of Kurdish, Arab, and other forces supported by the US government.[30] Nearly all the incidents HRW documented appeared to have been caused by improvised mines, rather than by explosives detonated by a vehicle or by remote-control.

Use by non-state armed groups in other states not party

Pakistan

In March 2017, Pakistan reconfirmed that antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, and IEDs have been used by NSAGs throughout the country.[31] NSAGs in Balochistan and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa used antipersonnel landmines and victim-activated explosive devices during the reporting period. Pakistan’s Parliamentary Committee on SAFRON (State and Frontier Regions) urged the government to establish a fund for the victims of landmine blasts. The committee expressed discontentment that at least 50 people have died and hundreds of others have been injured in landmine blasts in South Waziristan agency alone. It noted that according to a rough estimate, about 10,000 landmines are laying in the Mehsud inhabited area, which need to be removed before they claim further lives.[32]

Use has been attributed to Tehrik Taliban Pakistan and Balochistan insurgent groups as well as clan feuds.[33] In April 2016, a representative of Pakistan told the Monitor that 14% of recovered IEDs used by militants in Pakistan are victim-activated. The explosive devices are victim-activated through pressure-plate and infra-red initiation. Sometimes these improvised antipersonnel mines are used as detonators for larger explosive devices, or one initiator will set off multiple explosive devices.[34]

India

In July 2017, the Deputy Inspector General of Police in Chhatisgarh state informed the state news agency that “Pressure IEDs planted randomly inside the forests in unpredictable places, where frequent de-mining operations are not feasible, remain a challenge.”[35] The use of these victim-activated improvised mines was attributed by the police to the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-M) and its armed wing, the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army.[36] In September 2017, an elephant was killed after it stepped on a landmine attributed to the CPI-M in Jharkhand state.[37] In May 2017, India’s Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) recovered a cache of 53 landmines, in Jharkhand state and in December 2016, the CRPF recovered another cache of 120 landmines, also in Jharkhand state.[38]

Use by non-state armed groups in States Parties

Afghanistan

Use of improvised mines and other IEDs by anti-government elements in 2016 and 2017 resulted in further casualties. In June, Afghanistan informed States Parties that new use of pressure-plate improvised mines, which are causing approximately 60 deaths a month, was adding to their clearance burden and making it hard to meet their Article 5 obligations.[39] There have been no reports of antipersonnel mine use by coalition or Afghan national forces.

The use of improvised mines in Afghanistan is mainly attributed to the Taliban, Haqqani Network, and IS. The UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) reported that anti-government forces used victim-activated improvised mines in decreasing numbers throughout 2016 and the first half of 2017. However, UNAMA also reported that use of pressure-plate improvised mines[40] substantially contributed to the increases in both woman and child casualties and a 42% increase in civilian deaths by improvised mines compared to the same period in 2016.[41]

Iraq

While there were not any reports of use of antipersonnel mines by government forces or its international coalition partners, IS forces fighting the government of Iraq have used improvised landmines, other types of IEDs, and victim-activated booby-traps extensively since 2014.[42]

IS continued its extensive use of improvised landmines into 2017. In Mosul, scores of civilians were killed by improvised mines while attempting to flee fighting between IS and Iraqi Federal Police units.[43] The group has also planted improvised mines around mass graves, in an effort to kill investigative journalists and aid workers.[44] As IS continues to lose ground in Iraq, it consistently leaves improvised mines and booby-traps behind as it retreats.[45] Between September 2015 and January 2017, MAG cleared 7,500 improvised mines and other improvised devices from Iraq and Syria.[46]

Nigeria

Boko Haram militants have allegedly been laying unspecified types of landmines and victim-activated IEDs in Nigeria since mid-2014.[47] In both 2016 and early 2017, UNMAS identified ongoing extensive use of improvised mines by the Boko Haram group in northern areas of Nigeria. UNMAS also received reports of possible use of factory-made antipersonnel mines.[48] A number of incidents occurred apparently from the use improvised mines. On 21 August 2017, at least two Nigerian cattle farmers were killed and three severely injured when they stepped on a landmine while traveling to Biu, Borno state. The civilians were apparently attempting to flee a Boko Haram ambush, and were running across fields when they triggered the landmine, allegedly planted by the insurgents.[49]

Ukraine

Landmine Monitor has received no information that Ukrainian government forces have used antipersonnel mines in violation of the Mine Ban Treaty in 2016–2017.[50] Since 2014, the government of Ukraine has stated that it has not used antipersonnel mines in the conflict and has accused Russian-supported forces of laying landmines in Ukraine.[51] In December 2014, Ukrainian government officials stated that “no banned weapons” had been used in the “Anti-Terrorist Operations Zone” by Ukrainian armed forces or forces associated with them, such as volunteer battalions.[52]

There is significant evidence present at different locations that antipersonnel mines of Soviet-origin with production markings from the 1980s as well as antipersonnel mines with production markings from the 2000s, indicating Russian origin, are available.[53] Ukrainian armed forces and the security services continue to confiscate caches of antipersonnel landmines along the front line, including MON-50 directional mines,[54] MON-90 directional mines,[55] PMN-1 and PMN-2 blast mines,[56] and POM-2 scatterable mines.[57] Ukrainian soldiers were killed or wounded by antipersonnel mines in 2017 on 2 October, 11 August, 15 July, and on 9 May.[58] In September 2016, Ukraine’s Department of Defense Intelligence reported that separatists had laid POM-2 antipersonnel mines.[59] Later that month, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s (OSCE) Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine reported the presence of antivehicle and antipersonnel mines that it said were preventing the SMM representatives from traveling from Pervomaisk toward Zolote, between Mykolaiv province and Luhansk province.[60] In April 2017, an international OSCE observer was killed and two others injured by an antivehicle mine in Luhansk region.[61]

Yemen

Due to the extremely limited access to the country, it is not clear if antipersonnel landmines were used in Yemen in 2017. However, new use was recorded during late 2016 and in previous years.

In April 2017, HRW reported evidence of new use of antipersonnel mines in the governorates of Aden, Marib, Sanaa, and Taizz in 2015–2016.[62] It attributed responsibility for this mine use to Houthi forces and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh. In September 2016, HRW reported Houthi-Saleh forces’ use of antipersonnel mines in Aden, Abyan, Marib, Lahj, and Taizz governorates in 2015–2016.[63]

HRW also reported that the Islamist armed group Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which is also a party to the conflict, used antipersonnel mines in Yemen in 2016.[64]

On 2 April 2017, Yemen’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is controlled by the Houthis and Saleh’s General People’s Congress Party, denied that Houthi-Saleh forces had used antipersonnel landmines, affirming the Sanaa-based authorities are “vigilant in abiding by [their] commitments” under the Mine Ban Treaty.[65]

In early 2017, a UN Panel of Experts on Yemen reported that Houthi-Saleh forces have used victim-activated IEDs that deployed antivehicle mines as the main charge in Taizz.[66] Antivehicle landmines claimed casualties in Bayda governorate in October 2017 and Jawf governorate in April 2017, but it is unclear when those mines were laid.[67]

A joint operation by a coalition of states led by Saudi Arabia against Houthi forces in Yemen was continuing as of October 2017. Although there is evidence of use of cluster munitions by members of this coalition, there has been no evidence to suggest that members of the Saudi Arabia-led coalition have used landmines in Yemen.

Allegations of new use and other reports

Landmine Monitor has also recorded allegations and other reports of new mine use by NSAGs in States Parties Cameroon, Chad, Mali, Niger, Philippines, and Tunisia, as well as states not party Iran and Saudi Arabia. The Monitor cannot confirm use in any of these instances.

Various media outlets have continued to report new “landmine” use by Boko Haram militants in Chad and Niger.[68] Landmine Monitor has not confirmed the nature of the devices used or the circumstances of the allegations.

In Cameroon, allegations of use by Boko Haram of improvised antipersonnel mines have been reported in the northern extreme of the country where it shares borders with Nigeria and Chad. Boko Haram has been documented to manufacture and use improvised antipersonnel mines across the border in Nigeria. In 2015, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported the presence of landmines in Cameroon’s Fotokol and Mayo Moskota, both in Logone et Chari department.[69] In 2016 and early 2017, UNMAS identified use of improvised mines by Boko Haram in northern Cameroon, but did not indicate if these were antipersonnel mines or antivehicle mines.[70]

In August 2016 in Libya, an allegation surfaced that IS militants laid landmines sometime prior to being forced out of Derna in eastern Libya in mid-2015. The Monitor is not in a position to verify the allegation.[71] According to media reports, IS militants laid landmines and victim-activated explosive devices around Sirte.[72]

In Mali, 39 casualties were reported to be caused by improvised mines being detonated by vehicles. Handicap International indicates that these devices, equipped with a pressure-plate initiating mechanism, could be activated upon contact or by the weight of a person. However, they have only been reported to be activated by either vehicles or command detonation.[73]

In the Philippines, in May 2017, the Philippines Army was engaged in armed conflict with an Islamist armed group in Marawi,[74] Mindanao, who reportedly used improvised mines resulting in casualties.[75] There have also been periodic reports of improvised mine use by Abu Sayyaf.[76] In 2017, the Monitor was provided a technical drawing of New People’s Army/Communist Party of the Philippines command-detonated landmines fitted with an antihandling device that can be turned on or off manually.[77]

In Tunisia, NSAGs in Jebel Al-Cha’anby in Qsrein Wilaya/Kasserine governorate near the Algerian border have allegedly laid improvised antipersonnel mines. The Monitor could not independently confirm this. Casualties of improvised mines sometimes referred to as “landmines” continued to be reported in 2016 and early 2017.[78]

Saudi Arabia has reported that soldiers have been injured by landmines on its border with Yemen. In 2016 and 2017, reports of mine use and seizures have occurred in Aseer and Jazan provinces. Saudi Arabia has blamed Houthi forces as well as smugglers for using antipersonnel mines.[79]

Stockpiles of antipersonnel landmines possessed by states not party and non-state armed groups

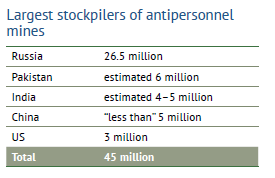

The Monitor estimates that as many as 31 of the 35 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty stockpile antipersonnel landmines. In 1999, the Monitor estimated that, collectively, states not party stockpiled about 160 million antipersonnel mines, but today the global total may be less than 50 million.[80]

It is unclear if all 31 states are currently stockpiling antipersonnel mines. Officials from the UAE have provided contradictory information regarding its possession of stocks, while Bahrain and Morocco have stated that they have only small stockpiles used solely for training purposes in clearance and detection techniques.

Three states not party, all in the Pacific, have said that they do not stockpile antipersonnel mines: Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Tonga. In its 2012 voluntary transparency report, Palestine stated that it does not possess a stockpile of antipersonnel mines, and it does not retain any mines for training purposes.

States not party to the Mine Ban Treaty routinely destroy stockpiled antipersonnel mines as an element of ammunition management programs and the phasing out of obsolete munitions. In recent years, such stockpile destruction has been reported in China, Israel, Mongolia, Pakistan, Russia, the US, and Vietnam.

Non-state armed groups

Fewer NSAGs appear to be able to obtain factory-made antipersonnel mines now that production and transfers have largely halted under the Mine Ban Treaty. Some NSAGs in states not party have acquired landmines by stealing them from government stocks, purchasing them from corrupt officials, or removing them from minefields. Most appear to make their own improvised landmines from locally available materials.

During this reporting period, NSAGs and criminal groups in Afghanistan, India, Iraq, Libya, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Syria, Ukraine, Yemen, and Western Sahara were reported to possess stocks of factory-made antipersonnel mines or components to manufacture improvised landmines. The Monitor largely relies on reports of seizures by government forces, reports of significant use, or verified photographic evidence from journalists to identify NSAGs possessing mine stockpiles.

Production of antipersonnel mines

More than 50 states produced antipersonnel mines at some point in the past.[81] Forty-one states have ceased production of antipersonnel mines, including four that are not party to the Mine Ban Treaty: Egypt, Israel, Nepal, and the US.[82]

In November 2015, Singapore Technologies Engineering announced that it had ceased production of antipersonnel mines and published the decision on its website in a section entitled “Sustainability Governance.”[83] In a letter to PAX, a Dutch NGO, the company’s President Tan Pheng Hock stated, “ST Engineering is now no longer in the business of designing, producing and selling of anti-personnel mines and cluster munitions or any related key components.”[84] The Monitor will continue to list Singapore as a producer until the government formally commits to no future production. Singapore already observes an indefinite export moratorium.

The Monitor identifies 11 states as producers of antipersonnel mines, unchanged from the previous report: China, Cuba, India, Iran, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, and Vietnam. Most of these countries are not believed to be actively producing mines but reserve the right to do so. Those most likely to be actively producing are India, Myanmar, Pakistan, and South Korea.

Production of antipersonnel mines by India appeared to be ongoing in 2016 and 2017. Purchase order records retrieved from a publicly accessible online government transaction database list at least a dozen private companies providing components of M-16, M-14, and APER 1B antipersonnel mines to the Indian Ordnance Factories in late 2016 and throughout 2017.[85] Components were produced under these contracts and supplied to the Ammunition Factory Khadki and Ordnance Factory Chandrapur, both in Maharashtra state.[86] In February 2017, a private Indian arms manufacturer had components for bounding fragmentation antipersonnel landmines listed within their sales catalogue on display at the IDEX military trade event in Abu Dhabi.[87]

NSAGs in countries including Afghanistan, Cameroon, Iraq, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Syria make antipersonnel mines. MAG reported in November 2016 that IS produced near factory quality improvised mines on a large scale.[88]

Transfers of antipersonnel mines

A de facto global ban on the transfer of antipersonnel mines has been in effect since the mid-1990s. This ban is attributable to the mine ban movement and the stigma attached to antipersonnel mines.

Landmine Monitor has never conclusively documented any state-to-state transfers of antipersonnel mines since it began publishing annually in 1999. However, the use of factory-produced antipersonnel mines in conflicts in Ukraine and Yemen, where declared stockpiles had been destroyed, indicates that some transfers, either internally among actors or from sources external to the country, are occurring.

Three types of antipersonnel mines produced in the 1980s have been used in Yemen since 2013: PPM-2 mines, GYATA-64 mines, and Bulgarian-made PSM-1 bounding fragmentation mines. None of these mines were among the four types of antipersonnel mines that Yemen reported stockpiling in the past. This indicates that Yemen’s 2002 declaration to the UN Secretary-General on the completion of landmine stockpile destruction was incorrect or incomplete, or that these mines were acquired from another source after 2002. In a September 2016 letter, Yemen’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Sanaa, controlled by the Houthis and the General People’s Congress, said that individuals had smuggled weapons, including landmines, into Yemen in recent years, noting that the current government had not been able to control its land or sea borders due to instability and fighting.[89]

The State Security Service of Ukraine reported seizing and recovering antipersonnel mines from Russian-backed separatists during 2016, including 24 MON-series directional fragmentation munitions, five OZM-72 bounding fragmentation mines, and one PMN-2 blast mine.[90]

In 2017, Ukrainian authorities continue to confiscate caches of antipersonnel mines, including MON-50 directional mines,[91] MON-90 directional mines,[92] PMN-1 and PMN-2 blast mines,[93] and POM-2 scatterable mines.[94] Ukraine completed its destruction of stockpiled PMN mines in 2003; other mine types are possessed by Russia, Ukraine, and any number of successor states of the Soviet Union.

At least nine states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, including six landmine producers, have enacted formal moratoriums on the export of antipersonnel mines: China, India, Israel, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, and the US. Other past exporters have made statements declaring that they have stopped exporting, including Cuba and Vietnam. Iran also claims to have stopped exporting in 1997, despite evidence to the contrary.[95]

In February 2017, the Egyptian Ministry of Military Production advertised “Heliopolis plastic antipersonnel landmines” for sale at its display at the IDEX arms fair in Abu Dhabi.[96] Egyptian authorities did not respond to a June 2017 request by the Monitor for further information regarding the apparent change in policy on export, and possibly production, indicated by the IDEX sales brochure. In December 2012, Egypt said that it “imposed a moratorium on its capacity to produce and export landmines in 1980.”[97]

Universalizing the landmine ban

Since the Mine Ban Treaty entered into force on 1 March 1999, states that had not signed it by then may no longer sign and ratify the treaty but must accede, a process that essentially combines signature and ratification. Of the 162 States Parties, 132 signed and ratified the treaty, while 30 acceded.[98]

The last country to accede to the Mine Ban Treaty was Oman on 20 August 2014.

The 35 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty include the Marshall Islands, which is the last signatory yet to ratify.

On 2 March 2016, Ambassador Ravinatha Pandukabhaya Aryasinha announced that Sri Lanka’s cabinet of ministers has approved accession to the Mine Ban Treaty, but the instrument of accession had not been deposited with the UN as of 31 October 2017.[99]

The US government announced policy measures in June and September 2014 banning US production and acquisition of antipersonnel landmines, accelerating stockpile destruction, and banning mine use, except on the Korean Peninsula.[100] The Obama administration also indicated its “aspiration” for the US to “eventually accede to the Ottawa Convention,” but there have been few signs of new steps toward that goal.[101] The administration of Donald Trump has not indicated if US landmine policy will be revisited.

Annual UN General Assembly resolution

Since 1997, the annual UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolution has provided states outside the Mine Ban Treaty with an important opportunity to indicate their support for the humanitarian rationale of the treaty and the objective of its universalization. A dozen countries that have acceded to the Mine Ban Treaty since 1999 did so after voting in favor of consecutive UNGA resolutions.[102]

On 5 December 2016, UNGA Resolution 71/34 calling for universalization and full implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty was adopted by a vote of 164 in favor, none against, and 20 abstentions.[103] This is a decrease in votes in favor from the 2015 resolution of 168 states in favor, none against, and 17 abstentions, which was the highest number of affirmative votes for the annual resolution.[104] Regrettably, Mine Ban Treaty States Parties Kuwait, Nicaragua, and Samoa abstained from voting on the annual resolution in 2016.

A core of 14 states not party have abstained from consecutive Mine Ban Treaty resolutions, most of them since 1997: Cuba, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, Syria, Uzbekistan, the US, and Vietnam.[105]

Non-state armed groups

Some NSAGs have expressed a willingness to observe the ban on antipersonnel mines, which reflects the strength of the growing international norm and stigmatization of the weapon. At least 65 NSAGs have committed to halt using antipersonnel mines since 1997.[106] The exact number is difficult to determine, as NSAGs have no permanence, frequently split into factions, go out of existence, or become part of state structures.

In Colombia, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo, FARC) and the Colombian government signed an agreement in November 2016 to end the armed conflict. This halted the FARC’s widespread use of improvised antipersonnel landmines and resulted in the surrender and destruction of its stockpile (see below). On 1 October 2017, a ceasefire agreement between the government of Colombia and the National Liberation Army (Unión Camilista-Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN) took effect.[107] In the agreement, the ELN committed not to use antipersonnel landmines that could endanger the civilian population.

Convention on Conventional Weapons

Amended Protocol II of the 1980 Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) entered into force on 3 December 1998 and regulates the production, transfer, and use of landmines, booby-traps, and other explosive devices. Weaknesses of the original protocol and inadequate measures to improve it through Amended Protocol II gave impetus to the Ottawa Process that resulted in the Mine Ban Treaty.

As of October 2017, a total of 104 states were party to Amended Protocol II. Only 10 of these states have not joined the Mine Ban Treaty: China, Georgia, India, Israel, Morocco, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, and the US. Therefore, for antipersonnel mines, the protocol is only relevant for those 10 countries as the 94 other states are bound by the much higher standards provided by the Mine Ban Treaty.

The original Protocol II on mines, booby-traps, and other devices entered into force on 2 December 1983 and has largely been superseded by the 1996 Amended Protocol II, but 13 states that are party to the original protocol have yet to ratify the amended protocol.[108]

A total of 17 states that stockpile antipersonnel mines are not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, CCW Amended Protocol II, or CCW Protocol II. Five of these states are also landmine producers.

Status and Operation of the Mine Ban Treaty

In general, States Parties’ implementation of and compliance with the Mine Ban Treaty has been excellent. The core obligations have largely been respected, and when ambiguities have arisen they have been dealt with in a satisfactory manner. However, there are serious compliance concerns regarding a small number of States Parties with respect to use of antipersonnel mines and missed stockpile destruction deadlines. In addition, some States Parties are not doing nearly enough to implement key provisions of the treaty, including those concerning mine clearance and victim assistance, which are detailed in other chapters of this report.

At the Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference in June 2014, States Parties created a new Committee on Cooperative Compliance to consider whether a concern about compliance with the prohibitions contained in Article 1.1 is potentially credible and, if so, to consider any follow-up that might be appropriate for States Parties.[109]

The Committee on Cooperative Compliance most recently provided a report on its activities to the intersessional meetings in June 2017.[110] According to the report, beginning in January 2017, the committee met with representatives of South Sudan, Sudan, Ukraine, and Yemen to continue its cooperative dialogue regarding allegations of use of antipersonnel mines. Previously, at the 15th Meeting of States Parties in November 2016, the president, in her capacity as the chair of the Committee on Cooperative Compliance presented the activity report of the committee’s work in 2016, which mainly comprised of dialogue with representatives of States Parties Sudan, South Sudan, Ukraine, and Yemen.[111]

In September 2017, the President of the Mine Ban Treaty, Thomas Hajnoczi, Ambassador of Austria to the UN, contacted Myanmar, a state not party to the treaty, regarding new mine use allegations. He stated, “I have asked the government of Myanmar to clarify the situation and consider an independent fact-finding mission with international participation into this matter. Any use of anti-personnel mines, an indiscriminate weapon which has dire consequences on civilian populations, is of grave concern to the States Parties of our Convention.”

Use of antipersonnel mines by States Parties

In this reporting period, commencing October 2016, there have been no allegations of use of antipersonnel mines by government forces of States Parties.

Until Landmine Monitor Report 2013, there had never been a confirmed case of use of antipersonnel mines by the armed forces of a State Party since the Mine Ban Treaty became binding international law in 1999. That has no longer been the case since Yemen confirmed that its forces violated the convention by using antipersonnel mines in 2011.

The Mine Ban Treaty’s Committee on Cooperative Compliance continued to follow-up on past allegations of antipersonnel mine use from previous years by the armed forces of South Sudan (in 2013 and 2011), Sudan (in 2011), Ukraine (in 2014), and Yemen (in 2011).

Stockpile destruction

At least 157 of the 162 States Parties do not stockpile antipersonnel mines. This includes 92 states that have officially declared completion of stockpile destruction and 65 states that have declared they never possessed antipersonnel mines (except in some cases for training in detection and clearance techniques).

Collectively, States Parties have destroyed more than 53 million stockpiled antipersonnel mines, including more than 2.2 million destroyed in 2016.

On 5 April 2017, the Ministry of Defense of Belarus confirmed in a statement that it “has fully fulfilled its international obligations under the Ottawa Convention,” by completing the destruction of “3.4 million antipersonnel mines PFM-1 with the support of the European Union.”[112] Belarus had a deadline of 1 March 2008 to destroy all stockpiles of antipersonnel mines under its jurisdiction or control.

Poland completed the destruction of its stockpile in April 2016, more than a year before its deadline.[113] Poland began destroying its stockpile of more than one million antipersonnel mines in 2003.[114]

Three States Parties possess more than 5.5 million antipersonnel mines remaining to be destroyed: Ukraine (4.9 million), Greece (643,267), and Oman (7,630). It is uncertain if two other States Parties possess stocks. Tuvalu has not made an official declaration, but is not thought to possess antipersonnel mines. Somalia acknowledged that “large stocks are in the hands of former militias and private individuals,” and that it is “putting forth efforts to verify if in fact it holds antipersonnel mines in its stockpile.”[115]

Oman destroyed 3,052 antipersonnel mines during 2016.[116] To date, Oman has declared the destruction of 4,578 antipersonnel mines, 30% of its stockpile. It has committed to destroy its stockpile by the deadline of 1 February 2019.

Greece and Ukraine remain in violation of Article 4 after failing to complete the destruction of their stockpiles by their four-year deadline.[117] The Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 called on States Parties that missed their deadline to comply without delay, and also to communicate their plans to do so, to request any assistance needed, and to provide an expected completion date. The Maputo Action Plan added a call for these states to provide a plan for the destruction of their remaining stockpiles by 31 December 2014.

Complicated legal and contractual issues surrounding the destruction of Greece’s stockpile of antipersonnel mines continue to stall any physical destruction. This situation is further complicated by the stockpiles being located in both Greece and Bulgaria. Greece stated at the 2017 intersessional meetings that “the remaining stockpile will be destroyed over a period of 20 months after the signature of a revised contract with the MOD [Ministry of Defense], notwithstanding of course any future unforeseen circumstances beyond our control.”[118]

At the May 2016 intersessional meetings, Ukraine stated that on 19 October 2015 an additional agreement was reached among the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, NATO Support and Procurement Agency, and the Pavlograd Chemical Plant for the resumption of the destruction of stockpiles of PFM-type antipersonnel mines. Ukraine reported the destruction of 652,840 mines in 2016, an increase from 19,944 destroyed mines in 2015.[119] Ukraine has not detailed any plans to destroy stockpiled POM-2 antipersonnel mines.

The FARC in Colombia were previously known to be a major producer of antipersonnel mines. Disarmament of the FARC, including destruction of its antipersonnel landmine stockpile and components occurred under UN supervision. Disarmament was completed on 22 September 2017. The UN mission destroyed 3,528 antipersonnel mines formerly belonging to the FARC, as well as components, including more than 38,000 kilograms of explosives and more than 46,000 detonators.[120]

Mines retained for training and research (Article 3)

Article 3 of the Mine Ban Treaty allows a State Party to retain or transfer “a number of anti-personnel mines for the development of and training in mine detection, mine clearance, or mine destruction techniques…The amount of such mines shall not exceed the minimum number absolutely necessary for the above-mentioned purposes.”

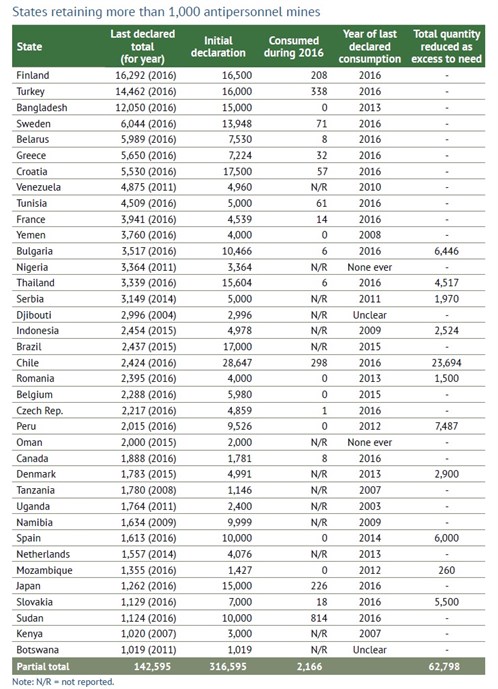

A total of 71 States Parties have reported that they retain antipersonnel mines for training and research purposes, of which 37 retain more than 1,000 mines and three (Finland, Turkey, and Bangladesh) each retain more than 12,000 mines. Eighty-six States Parties have declared that they do not retain any antipersonnel mines, including 34 states that stockpiled antipersonnel mines in the past. On 18 September 2017, Algeria destroyed the 5,970 antipersonnel mines it retained for training purposes after completing its landmine clearance program.

In addition to those listed above, another 34 States Parties each retain fewer than 1,000 mines and together possess a total of 13,746 retained mines.[121] This amount is 479 more retained mines than reported for the previous year, due to Bosnia and Herzegovina and Cambodia dropping below the 1,000-mine threshold.

While laudable for transparency, several States Parties are still reporting as retained antipersonnel mines devices that are fuzeless, inert, rendered free from explosives, or otherwise irrevocably rendered incapable of functioning as an antipersonnel mine, including by the destruction of the fuzes. Technically, these are no longer considered antipersonnel mines as defined by the Mine Ban Treaty; a total of at least 12 States Parties retain antipersonnel mines in this condition.[122]

The ICBL has expressed concern at the large number of States Parties that are retaining mines but apparently not using those mines for permitted purposes. For these States Parties, the number of mines retained remains the same each year, indicating none are being consumed (destroyed) during training or research activities. No other details have been provided about how the mines are being used. A total of eight States Parties have never reported consuming any mines retained for permitted purposes since the treaty entered into force for them: Burundi, Cape Verde, Cyprus, Djibouti, Nigeria, Oman, Senegal, and Togo.

Transparency reporting

Article 7 of the Mine Ban Treaty requires that each State Party “report to the Secretary General of the United Nations as soon as practicable, and in any event not later than 180 days after the entry into force of this Convention for that State Party” regarding steps taken to implement the treaty. Thereafter, States Parties are obligated to report annually, by 30 April, on the preceding calendar year.

Only one State Party has not submitted an initial report: Tuvalu (due 28 August 2012).

As of 31 October 2017, 47% of States Parties had submitted annual reports for calendar year 2016, an increase from the previous year (45%). A total of 85 States Parties have not submitted a report for calendar year 2016. Of this latter group, most have failed to submit an annual transparency report for two or more years.[123]

No state that is currently not party to the treaty submitted a voluntary report in 2016. In previous years, Morocco (2006, 2008–2011, and 2013), Azerbaijan (2008 and 2009), Lao PDR (2010), Mongolia (2007), Palestine (2012 and 2013), and Sri Lanka (2005) submitted voluntary reports.

Iraq, Tunisia, Nigeria, and other states with recent allegations or confirmed reports of use of improvised landmines by NSAGs have failed to provide information on new contamination in their annually updated Article 7 reports.

[1] Statement by the ICBL, Mine Ban Treaty 15th Meeting of States Parties, Santiago, 30 November 2016, bit.ly/ICBL15MSP30Nov.

[2] Explanation of vote by Austria, UN General Assembly (UNGA) First Committee on Disarmament and International Security, New York, 31 October 2017.

[3] NSAGs used mines in at least 10 countries in 2015–2016 and 2014–2015, seven countries in 2013–2014, eight countries in 2012–2013, six countries in 2011–2012, four countries in 2010, six countries in 2009, seven countries in 2008, and nine countries in 2007. NSAGs often use improvised mines, rather than factory-made antipersonnel mines. In the reporting period, there were also reports of NSAG use of antivehicle mines in Afghanistan, Cameroon, Iraq, Kenya, Lebanon, Mali, Niger, Pakistan, Philippines, Somalia, Syria, Tunisia, Ukraine, and Yemen.

[4] “Colombia Cease-Fire Agreement Takes Effect Sunday,” Voice of America, 30 September 2017, www.voanews.com/a/colombia-cease-fire-takes-effect-october-1/4050834.html.

[5] “Pyithu Hluttaw hears answers to questions by relevant ministries,” Global New Light of Myanmar, 13 September 2016, www.burmalibrary.org/docs23/GNLM2016-09-13-red.pdf.

[6] Landmine Monitor meeting with Min Htike Hein, Assistant Permanent Secretary to the Minister for Defense, Naypyitaw, 26 June 2017.

[7] Email and phone interviews with researchers working with an NGO assisting displaced Rohingya civilians who wished to remain anonymous, 17 September 2017. According to the researchers, the mines were emplaced within Taung Pyo Let Yar village tract of Maungdaw township, adjacent to border pillar No. 31 in Bangladesh, an area that demarcates the beginning of the land border between Bangladesh and Myanmar. Researchers told Landmine Monitor that the landmine use continued over the following days, progressing northeast along the border within the townships of Mee Taik, Nga Yant Chaung, Hlaing Thi, Bauk Shu Hpweit, and In Tu Lar.

[8] Krishna N Das, “Exclusive: Bangladesh protests over Myanmar’s suspected landmine use near border,” Reuters, 5 September 2017, bit.ly/ReutersBangladesh5Sep17; and Ananya Roy, “Bangladesh accuses Myanmar government of laying landmines near border,” International Business Times, 6 September 2017, bit.ly/IBTlandmine6Sep17.

[9] S. Bashu Das, “2 Rohingya children injured in landmine blast near Naikhongchhari border,” Dhaka Tribune, 5 September 2017, bit.ly/Rohingyachildren5Sep17.

[10] Amnesty International, “Myanmar Army landmines along border with Bangladesh pose deadly threat to fleeing Rohingya,” 9 September 2017, bit.ly/AIMyanmer9Sep17.

[11] HRW, “Landmines Deadly for Fleeing Rohingya: Military Lays Internationally Banned Weapon,” 23 September 2017, www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/23/burma-landmines-deadly-fleeing-rohingya.

[12] Tun Lin Aung, “Landmines scare Myitkyina farmers,” Eleven Myanmar, 2 June 2017, www.elevenmyanmar.com/local/9806.

[13] Ye Mon and Ei Ei Thu, “Kayin landmine scare sparks tourism fears,” Myanmar Times, 6 January 2017, www.mmtimes.com/national-news/24435-explosion-reignites-landmine-fears.html.

[14] “Landmine explosion kills two Kia troops,” Global New Light of Myanmar, 29 November 2016, www.burmalibrary.org/docs23/GNLM2016-11-29-red.pdf.

[15] Unpublished information provided to the Landmine Monitor by the Karen Human Rights Group, 6 September 2017. This DKBA faction has been referred to as DKBA #907, Kloh Htoo Baw (Golden Drum), and Brigade #5. Each of these terms refers to different configurations of DKBA units commanded by the brigadier general commonly known as Na Kha Mway, whose real name is Saw Lah Pwe. See also, “Landmine kills Kayin village head,” Eleven Myanmar, 17 September 2016, www.elevenmyanmar.com/local/5972.

[16] ICBL Press Release, “ICBL publicly condemns reports of Syrian forces laying mines,” 2 November 2011, www.icbl.org/en-gb/news-and-events/news/2011/icbl-publicly-condemns-reports-of-syrian-forces-la.aspx.

[17] “Assad troops plant land mines on Syria-Lebanon border,” The Associated Press, 1 November 2011, www.haaretz.com/news/middle-east/assad-troops-plant-land-mines-on-syria-lebanon-border-1.393200.

[18] MSF, “Syria: Siege and Starvation in Madaya,” 7 January 2016, www.doctorswithoutborders.org/article/syria-siege-and-starvation-madaya.

[19] See, “Injured by one of 8,000 landmines in desperate escape bid, Madaya man faces double amputation,” Syria Direct, 5 October 2016, bit.ly/SyriaDirect5Oct2016; Syrian American Medical Association, “Madaya: Starvation Under Siege,” January 2016, p. 1, www.sams-usa.net/foundation/images/Report_Madaya_Starvation_Under_Siege_.pdf; and Monitor email interview with Kristen Gillespie Demilio, Editor-in-Chief, Syria Direct, 7 October 2016.

[20] SNHR, “Civilians killed in ISIS landmine planted by ISIS in Kasrat Srour village in Raqqa governorate on September 23,” 24 September 2017, bit.ly/SNHR24Sep17.

[21] SNHR, “Civilians killed in ISIS’s landmine explosion in al Tayyar neighborhood in Raqqa city on September 14,” 16 September 2017, bit.ly/SNHR16Sep17; “Children killed in ISIS’s landmine explosion in Raqqa city on August 14,” SNHR, 15 August 2017, bit.ly/SNHR15Aug17; “A mother and her son killed by ISIS landmine explosion in Raqqa city on August 7,” SNHR, 8 August 2017, bit.ly/SNHR7Aug17; and “Victims killed by ISIS landmine explosion near the southern entrance of Raqqa city on August 4,” SNHR, 5 August 2017, bit.ly/SNHR5Aug17.

[22] SNHR, “Aziz Ajjan killed in ISIS’s landmine explosion in Hneida village in Raqqa governorate on August 6,” 7 August 2017, bit.ly/Raqqa7Aug.

[23] “IS land mine kills Syrian state TV photographer,” Associated Press (Beirut), 17 October 2017, www.foxnews.com/world/2017/10/10/latest-is-land-mine-kills-syrian-state-tv-photographer.html.

[24] “Children died in ISIS landmine explosion in Najm village in Aleppo governorate, August 23,” SNHR, London, 23 August 2016, bit.ly/sn4hr23Aug2016.

[25] SNHR,“Victims died due to ISIS landmine explosion in Abu Qalqal town in Aleppo governorate, September 2,” London, 2 September 2016, bit.ly/SNHR2Sep16.

[26] SNHR,“Civilians died due to ISIS landmines explosion in Mazyounet Al Humar village in Aleppo governorate, September 21,” London, 21 September 2016, bit.ly/SNHR21Sep16.

[27] SNHR, “Children died in ISIS landmine explosion in O’wn Al Dadat village in Aleppo governorate in October 4,” London, 4 October 2016, bit.ly/SNHR4Oct16.

[28] Lizzie Dearden, “Jac Holmes: British man who volunteered to fight against Isis killed in Syria,” The Independent, 24 October 2017, bit.ly/IndependentJacHolmes.

[29] Chris Loughran and Sean Sutton, “MAG: Clearing Improvised Landmines in Iraq,” The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction, Vol. 21, Issue 1, April 2017, http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal/vol21/iss1/.

[30] HRW Press Release, “Syria: Improvised Mines Kill, Injure Hundreds in Manbij,” 26 October 2016, www.hrw.org/news/2016/10/26/syria-improvised-mines-kill-injure-hundreds-manbij.

[31] CCW Amended Protocol II, Article 13 Report, Form B, 31 March 2017, bit.ly/PakCCWII2017.

[32] Email from Raza Shah Khan, Executive Director, Sustainable Peace and Development Organization (SPADO), 21 September 2017. He noted that media outreach and humanitarian response is very limited in South Waziristan but it has been confirmed that the local communities have carried out some other protests requesting the authorities to take immediate measures to clear the areas from landmines and ERW and provide support to the landmine victims.

[33] Email from Raza Shah Khan, SPADO, 21 September 2017.

[34] Presentation given by Pakistani delegation to the CCW Amended Protocol II Meeting of Experts, 6 April 2016, bit.ly/PakistanCCW6Apr2016; and Landmine Monitor interview with Pakistani delegation to the CCW Amended Protocol II Meeting of Experts, Geneva, 8 April 2016.

[35] Tikeshwar Patel, “IEDs pose huge challenge in efforts to counter Naxals: police,” Press Trust of India, 24 July 2017, www.ptinews.com/news/8915393_IEDs-pose-huge-challenge-in-efforts-to-counter-Naxals--police.

[36] The CPI-M and a few other smaller groups are often referred to collectively as Naxalites. The Maoists also have a People’s Militia with part-time combatants with minimal training and unsophisticated weapons.

[37] A.S.R.P. Mukesh, “Blast in tiger turf kills tusker,” The Telegraph, 21 September 2017, www.telegraphindia.com/1170922/jsp/frontpage/story_174397.jsp.

[38] “Over 50 landmines recovered in Jharkhand,” Statesman, 16 May 2017, www.thestatesman.com/cities/over-50-landmines-recovered-in-jharkhand-1494065802.html; and “120 land mines found in Latehar forest,” Times of India, 12 December 2016, bit.ly/landminesLatehar.

[39] Statement of Afghanistan, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Session on Clearance, Geneva, 8–9 June 2017, bit.ly/AfgClearanceInt2017.

[40] A pressure plate is a method for triggering a detonation of an explosive device by the pressure exerted by the weight of a person or a vehicle. If the device is capable of being triggered by the presence, proximity, or activity of a human being, it is banned under the Mine Ban Treaty.

[41] UNAMA, “Afghanistan: Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict mid-year report 2017,” Kabul, July 2017, p. 5, bit.ly/UNAMAAfgmid2017.

[42] See, for example, “ISIS’s latest threat: laying landmines,” IRIN, 6 November 2014, www.irinnews.org/news/2014/11/06/isis’s-latest-threat-laying-landmines; and Mike Giglio, “The Hidden Enemy in Iraq,” Buzzfeed, 19 March 2015, bit.ly/HiddenEnemyIraq.

[43] Kareem Khadder, Ingrid Formanek, and Laura Smith-Spark, “Mosul battle: Civilians killed by landmines as they flee, police say,” CNN, 25 February 2017, www.cnn.com/2017/02/25/middleeast/western-mosul-offensive/index.html.

[44] Lizzie Dearden, “Isis rigs mass grave with landmines to kill journalists and war crime investigators,” The Independent, 1 March 2017, bit.ly/ISISrigsgraves.

[45] “Islamic State is losing land but leaving mines behind,” The Economist, 30 March 2017, bit.ly/ISleavesmines.

[46] Chris Loughran and Sean Sutton, “MAG: Clearing Improvised Landmines in Iraq,” The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction, Vol. 21, Issue 1, April 2017, http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal/vol21/iss1/.

[47] See, for example, “Five killed in Boko Haram mine blast, ambush,” Vanguard, 21 June 2017, www.vanguardngr.com/2017/06/five-killed-boko-haram-mine-blast-ambush/.

[48] UNMAS, “Mission Report: UNMAS Explosive Threat Scoping Mission to Nigeria, 3 to 14 April 2017,” p. 2.

[49] “Au moins deux morts dans l’explosion d’une mine anti-personnelle au Nigeria,” Voice of America, 21 August 2017, bit.ly/VOANigeria21Aug17.

[50] Russia stated in October 2017, “We note with great regret that the information on alleged violations of Ottawa Convention is not verified at all. As we can see with regard to events in Ukraine the UN Secretary General investigation mechanism envisaged by Ottawa Convention remains inactive. Moreover, at the 2015-2016 State Parties meetings no one even tried to question Kiev’s compliance with Ottawa Convention during the civil war that it unleashed in the South-East of the country.” Statement by Vladimir Yermakov, UNGA First Committee Debate on Conventional Weapons, New York, 20 October 2017, http://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/1com/1com17/statements/20Oct_Russia.pdf.

[51] Submission of Ukraine, Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference, Maputo, Mozambique, 18 June 2014, www.maputoreviewconference.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC3/3RC-Ukraine-information.pdf; and statement of Ukraine, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Cooperative Compliance, Geneva, 26 June 2015, bit.ly/Ukraine26June2015

[52] In February 2016, Ukraine stated that “its Armed Forces are authorized to use mines in command-detonate mode, which is not prohibited under the Convention. All mines planted in command-detonate mode are recorded, secured and access is restricted.” “Report and Preliminary Observations Committee On Cooperative Compliance (Algeria, Canada, Chile, Peru and Sweden), 2016 Intersessional Meetings,” May 2016, p. 4, bit.ly/MBTComplianceMay2016. The Military Prosecutor confirmed to HRW that an assessment had been undertaken to ensure that stockpiled KSF-1 and KSF-1S cartridges containing PFM-1 antipersonnel mines, BKF-PFM-1 cartridges with PFM-1S antipersonnel mines, and 9M27K3 rockets with PFM-1S antipersonnel mines are not operational, but rather destined for destruction in accordance with the Mine Ban Treaty.

[53] Evidence of markings from 2003: Security Service of the Ukraine, “SBU reveals three hidings with ammunition and Russian mine in ATO area,” 15 November 2016, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/2256 - .cuYxfDr2.dpbs. Markings from 2010: Ukrainian Military TV, “Докази присутності російських військ на Донбасі,” YouTube.com, 1 March 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfA7c4iBBlU.

[54] Ukrainian Military TV, “Докази присутності російських військ на Донбасі,” YouTube.com, 1 March 2017, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfA7c4iBBlU; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals 2 Russian mines in ATO area,” 2 May 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3281 - .BFgZrg1s.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU seizes landmines produced in Russia in the ATO area,” 25 April 2017, www.ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/21/view/3227 - .o3KKyH3U.dpbs; and Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals cache with explosives in ATO area,” 16 January 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/2553#.gDmJqCLm.dpbs.

[55] Security Service of Ukraine, “СБУ виявила дві схованки зі зброєю та боєприпасами у районі проведення АТО,” 30 August 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/ua/news/1/category/1/view/3842#.ihBWxsxc.dpbs.

[56] “A stockpile of antipersonel mines retrieved from a separatist storage position,” Instagram Post by bring_me_the_swampy, 23 September 2017, www.instagram.com/p/BZZIg4_nnDx/?taken-by=bring_me_the_swampy; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals cache with mines, explosives and anti-tank grenade launchers in ATO area,” 27 April 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3253 - .FR2O7p8Y.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU seizes ammunitions of Russian origin in the ATO area,” 11 April 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3146 - .Kz15RzRS.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU records militants using weapons of Russian production,” 1 April 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3085 - .xM1gyOfw.dpbs; and Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals prohibited mines in ATO area that are in operational service with Russian army,” 16 May 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3354#.lejPDlBG.dpbs.

[57] Swampy, “Clearance around forward positions,” Beyond the Borders, 27 October 2017, http://swampy.freq.wtf/2017/10/27/3672/; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU prevents terrorist attacks prepared by Russian secret services in Mariupol,” 17 August 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3793 - .tidSa5nz.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU deactivates mine of Russian production in ATO area,” 26 April 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3236 - .GCLfhJGT.dpbs; and Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals three hidings with ammunition and Russian mine in ATO area,” 15 November 2016, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/2256#.Iyvz95Vv.dpbs.

[58] One killed in action (KIA) by OZM-72 mine in Bohdanivka, Mariupol: “Ministry of Defense: Russian sniper unit was deployed near Zaitseve,” Ukrainian Crisis Media Center, 2 October 2017, http://uacrisis.org/60925-polkovnyk-motuzyanyk-7; Three wounded and one killed in action by antipersonnel mines in Avdiivka and Zaitseve, Donetsk Oblast: “Зведення прес-центру штабу АТО” (“Briefing of the press center of the ATO headquarters”), ATO Press Center, 11 August 2017; One killed in action by antipersonnel mine in Shyrokyne, Mariupol: “Боєць з великої літери,” Five News, 18 July 2017, www.5.ua/regiony/boiets-z-velykoi-litery-dobrovoltsia-z-57i-bryhady-zsu-provely-v-ostanniu-put-150581.html. and one wounded by PMN-2 mine: Photos added to Facebook, by Vasyl Sakovets, Facebook, 15 June 2017, www.facebook.com/vasil.sakovets/posts/1350466698400599?aid=13P92Y.wghot.

[59] Ukraine Crisis Media Center, “Most militant attacks - in Mariupol direction – Col. Andriy Lysenko,” 3 September 2016, http://uacrisis.org/ua/46719-lisenko-20.

[60] “Latest from OSCE Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) to Ukraine, based on information received as of 19:30, 26 September 2016,” OSCE SMM to Ukraine, Kiev, 27 September 2016, www.osce.org/ukraine-smm/268961.

[61] “Landmine blast kills OSCE observer in Ukraine,” Al Jazeera, 23 April 2017, www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/04/land-blast-kills-osce-observer-ukraine-170423125142890.html.

[62] HRW, “Yemen: Houthi-Saleh Forces Using Landmines,” 20 April 2017, www.hrw.org/news/2017/04/20/yemen-houthi-saleh-forces-using-landmines.

[63] HRW, “Yemen: Houthi Landmines Claim Civilian Victims,” 8 September 2016, www.hrw.org/news/2016/09/08/yemen-houthi-landmines-claim-civilian-victims; HRW, “Yemen: New Houthi Landmine Use,” 18 November 2015, www.hrw.org/news/2015/11/18/yemen-new-houthi-landmine-use; and HRW, “Yemen: Houthis Used Landmines in Aden,” 5 September 2015, www.hrw.org/news/2015/09/05/yemen-houthis-used-landmines-aden.

[64] HRW, “Yemen: Houthi-Saleh Forces Using Landmines,” 20 April 2017, www.hrw.org/news/2017/04/20/yemen-houthi-saleh-forces-using-landmines.

[65] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Yemen response in letter to HRW, 2 April 2017, bit.ly/YemenHRW2Apr2017.

[66] HRW, “Yemen: Houthi-Saleh Forces Using Landmines,” 20 April 2017, www.hrw.org/news/2017/04/20/yemen-houthi-saleh-forces-using-landmines.

[67] Ali Owaida, “Landmine explosion kills 4 troops in central Yemen,” Anadolu Agency, 18 October 2017, http://aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/landmine-explosion-kills-4-troops-in-central-yemen/940837; and “Landmine explosion kills 2 soldiers in Yemen’s north,” Anadolu Agency, 30 April 2017, http://aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/landmine-explosion-kills-2-soldiers-in-yemens-north/808574.

[68] “Landmine Explosion Kills 6 Soilders at Niger-Nigerian Border,” Africa News, 8 January 2016, www.africanews.com/2016/01/18/landmine-explosion-kills-6-soilders-at-niger-nigerian-border/; Edwin Kindzeka Moki, “Boko Haram Land Mine Kills 2 in Cameroon Military Convoy,” The Daily Mail, 15 February 2016, www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/ap/article-3447888/Boko-Haram-land-kills-2-Cameroon-military-convoy.html; Edwin Kindzeka Moki, “Cameroon Vigilantes Hunt for Boko Haram Landmines,” Voice of America News, 4 March 2016, www.voanews.com/a/cameroon-vigilantes-hunt-for-boko-haram-landmines/3219444.html; “Fighting Boko Haram: Landmine seriously injures 3 Cameroonian service men,” Cameroon Concord, 8 June 2016,bit.ly/CameroonConcord8Jun2016; “Boko Haram landmine kills four Chadian soldiers,” Reuters, 27 August 2016, www.reuters.com/article/us-nigeria-security-chad-idUSKCN1120KY; and “Boko Haram Landmines Inflict Heavy Toll on Cameroon,” Latin America Herald Tribune, 29 June 2016, www.laht.com/article.asp?ArticleId=2415012&CategoryId=12395. Niger has not filed an updated Article 7 report since 2012, but noted in an Article 5 extension request of March 2016 that new contamination by Boko Haram had occurred. Chad submitted an annual Article 7 report in March 2016, but did not include any information on new contamination. Cameroon has not filed an updated Article 7 report since 2009 and has provided no official information to States Parties on any new contamination.

[69] UNHCR/International Organization for Migration (IOM), “Cameroon: Far North – Displaced Population Profiling,” 19 May 2015, bit.ly/UNCHRCameroon19May15.

[70] UNMAS, “Mission Report: UNMAS Explosive Hazard Mitigation Response in Cameroon 9 January – 13 April 2017,” p. 11.

[71] See, “Senior leader in Derna Shura Council killed by an ISIS landmine in Al-Heela,” Libyan Express, 1 August 2016, bit.ly/LibyaSnrLeader1Aug16.

[72] See, Lewis, A.,“Libya forces de-mine and clear Sirte after liberation from Isis militants,” The Independent, 11 August 2016, bit.ly/DemineSirte11Aug16; Sudarsan Raghavan, “Even with U.S. airstrikes, a struggle to oust ISIS from Libyan stronghold,” Washington Post, 7 August 2016, bit.ly/OustISISLibya7Aug17; and “A Sirte girl undergoes a massive 17-hour operation for landmine injuries,” The Libya Observer, 29 May 2016, bit.ly/SirteGirlLandmine.

[73] Email from Maddalena Malgarini, Technical Protection Coordinator, Handicap International-Mali, 26 September 2017.

[74] The group is most commonly referred to as the “Muate group,” but also has been known as Dawlah Islamiya and the Islamic State of Lanao, and is reported to be comprised of former MILF guerrillas and some foreign militants.

[75] See, “AFP: 2 soldiers lost legs after tripping on land mines in Marawi,” GMA News, 18 August 2017, bit.ly/AFPladnminesMarawi; and “Snipers, land mines delay liberation of Marawi City,” Business Mirror, 26 June 2017, http://businessmirror.com.ph/snipers-land-mines-delay-liberation-of-marawi-city/.

[76] Bong Garcia, “Bomb explosion kills farm owner in Basilan,” SunStar Zamboanga, 20 March 2017, www.sunstar.com.ph/zamboanga/local-news/2017/03/20/bomb-explosion-kills-farm-owner-basilan-531939.

[77] Technical drawings of “New People’s Army (NPA) Improvised Remote Firing Switch with integral anti‐lift device” based on a device recovered by Swiss Foundation for Mine Action (FSD) in June 2015 in Sarangani province, Mindanao. Provided to the Monitor by email, 9 September 2017.

[78] See, for example, “Tunisia landmine blasts kills shepherdess,” News24 (AFP), 17 June 2017, www.news24.com/Africa/News/tunisia-landmine-blasts-kills-shepherdess-20170616.

[79] See, “Saudi soldier killed by landmine near Yemen border,” Middle East Online, 9 December 2016, www.middle-east-online.com/english/?id=80238; and Mohammed Al-Sulami, “Saudi Border Guards stops efforts to plant land mines, smuggle weapons in southern Kingdom,” Arab News, 20 March 2017, www.arabnews.com/node/1071011/saudi-arabia#photo/7.

[80] In 2014, China informed Landmine Monitor that its stockpile is “less than” five million, but there is an amount of uncertainty about the method China uses to derive this figure. For example, it is not known whether antipersonnel mines contained in remotely-delivered systems, so-called “scatterable” mines, are counted individually or as just the container, which can hold numerous individual mines. Previously, China was estimated to have 110 million antipersonnel mines in stockpile.

[81] There are 51 confirmed current and past producers. Not included in that total are five States Parties that some sources have cited as past producers, but who deny it: Croatia, Nicaragua, Philippines, Thailand, and Venezuela. It is also unclear if Syria has produced antipersonnel mines.

[82] Additionally, Taiwan passed legislation banning production in June 2006. The 36 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty that once produced antipersonnel mines are Albania, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, BiH, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iraq, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Uganda, the UK, and Zimbabwe.

[83] See the Singapore Technologies Engineering 2015 annual report, www.stengg.com/media/30108/st-engineering-annual-report-2015.pdf. See also, Stop Explosive Investments, “Singapore Technologies Engineering stops production of cluster munitions,” 18 November 2015, bit.ly/STE18Nov2015. Investors received similar letters; and Local Authority Pension Fund Forum, “ST Engineering Quits Cluster Munitions,” 18 November 2015, www.lapfforum.org/press/files/20151118SingaporeTechnologiespressreleasefinal.pdf.

[84] Letter to PAX from Tan Pheng Hock, President and Chief Executive Officer, Singapore Technologies Engineering Ltd, 11 November 2015.

[85] Landmine Monitor complied a listing of “current contracts” showing who the contract was awarded to, and which companies applied for consideration, the number of units, cost and total cost and when it is to be delivered by plus other information. From Indian Ordnance Factories website at (accessed 9 November 2017) at: http://ofb.gov.in/index.php?wh=purchaseorders&lang=en. All current contracts are with one of two Indian Ordnance Factories located in Maharastra state, where the mines are assembled with components from private companies. Presumably they produce and add the explosive charge here, as no vendor provides more than fuzes, bodies, and other parts.

[86] The following companies were listed as having concluded contract listed for production of components of antipersonnel mines on the Indian Ordnance Factories Purchase Orders between October 2016 and November 2017: Sheth & Co., Supreme Industries Ltd., Pratap Brothers, Brahm Steel Industries, M/s Lords Vanjya Pvt. Ltd., Sandeep Metalkraft Pvt Ltd., Milan Steel, Prakash Machine Tools, Sewa Enterprises, Naveen Tools Mfg. Co. Pvt. Ltd., Shyam Udyog, and Dhruv Containers Pvt. Ltd. In addition the following companies had established contracts for the manufacture of mine components: Ashoka Industries, Alcast, Nityanand Udyog Pvt. Ltd., Miltech Industries, Asha Industries, and Sneh Engineering Works. Mine types indicated were either M-16, M-14, APERS 1B or “APM” mines, http://ofbindia.gov.in/index.php?wh=purchaseorders&lang=en. “From searching the Indian Ordnance Factories website at: http://ofb.gov.in/vendor/general_reports/show/registered_vendors/820 (accessed 8 November 2017).”

[87] Ashoka Manufacturing Limited, Marketing Brochure, undated, http://ashokagroup.net/brochures/defence.pdf. Brochure was observed on display at IDEX by Omega Research in February 2017. Email from Omega Research, 7 November 2017.

[88] MAG Policy Brief, “Humanitarian Response, Improvised Landmines and IEDs: Policy issues for principled mine action,” November 2016, www.maginternational.org/download/587908d82414d/.

[89] Letter to HRW from Yemen’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 7 September 2016, www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/supporting_resources/yemeni_mofa_response_to_hrw_landmines_sept_7_2016.pdf.

[90] All data taken from State Security Service of Ukraine website for 2016, starting at https://ssu.gov.ua/ua/news/27/category/21 and working backwards in time.

[91] Ukrainian Military TV, “Докази присутності російських військ на Донбасі,” YouTube.com, 1 March 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=QfA7c4iBBlU; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals 2 Russian mines in ATO area,” 2 May 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3281#.BFgZrg1s.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU seizes landmines produced in Russia in the ATO area,” 25 April 2017, https://www.ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/21/view/3227#.o3KKyH3U.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals cache with explosives in ATO area,” 16 January 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/2553#.gDmJqCLm.dpbs;

[92] Security Service of Ukraine, “СБУ виявила дві схованки зі зброєю та боєприпасами у районі проведення АТО,” 30 August 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/ua/news/1/category/1/view/3842#.ihBWxsxc.dpbs.

[93] Swampy, “Clearance around forward positions,” Beyond the Borders, 27 October 2017, http://swampy.freq.wtf/2017/10/27/3672/; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals cache with mines, explosives and anti-tank grenade launchers in ATO area,” 27 April 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3253#.FR2O7p8Y.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU seizes ammunitions of Russian origin in the ATO area,” 11 April 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3146#.Kz15RzRS.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU records militants using weapons of Russian production,” 1 April 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3085#.xM1gyOfw.dpbs; and Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals prohibited mines in ATO area that are in operational service with Russian army,” 16 May 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3354#.lejPDlBG.dpbs.

[94] Swampy, “Clearance around forward positions,” Beyond the Borders, 27 October 2017, http://swampy.freq.wtf/2017/10/27/3672/; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU prevents terrorist attacks prepared by Russian secret services in Mariupol,” 17 August 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3793#.tidSa5nz.dpbs; Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU deactivates mine of Russian production in ATO area,” 26 April 2017, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/3236#.GCLfhJGT.dpbs; and Security Service of Ukraine, “SBU reveals three hidings with ammunition and Russian mine in ATO area,” 15 November 2016, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/2256#.Iyvz95Vv.dpbs.

[95] Landmine Monitor received information in 2002–2004 that demining organizations in Afghanistan were clearing and destroying many hundreds of Iranian YM-I and YM-I-B antipersonnel mines, date stamped 1999 and 2000, from abandoned Northern Alliance frontlines. Information provided to Landmine Monitor and the ICBL by HALO Trust, Danish Demining Group, and other demining groups in Afghanistan. Iranian antipersonnel and antivehicle mines were also part of a shipment seized by Israel in January 2002 off the coast of the Gaza Strip.

[96] Brochure, Heliopolis Co. for Chemical Industries, National Organization for Military Production, Ministry of Military Production, Arab Republic of Egypt, p. 23. AP T78 and AP T79 plastic antipersonnel landmines. Received from Omega Research via Twitter, 3 March 2017, twitter.com/Omega_RF/status/836968523293405185.

[97] Statement of Egypt, “Explanation of Vote on Resolution on the Ottawa APLM Convention, L.8,” UNGA First Committee, New York, 2 December 2012, www.reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/1com/1com12/eov/L8_Egypt.pdf.

[98] The 30 accessions include two countries that joined the Mine Ban Treaty through the process of “succession.” These two countries are Montenegro (after the dissolution of Serbia and Montenegro) and South Sudan (after it became independent from Sudan). Of the 132 signatories, 44 ratified on or before entry into force (1 March 1999) and 88 ratified afterward.

[99] ICBL, “Sri Lanka decides to join Mine Ban Treaty,” 3 March 2016, www.icbl.org/en-gb/news-and-events/news/2016/sri-lanka-decides-to-join-mine-ban-treaty.aspx.

[100] Office of the Press Secretary, “Fact Sheet: Changes to U.S. Anti-Personnel Landmine Policy,” The White House, 23 September 2014, www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/23/fact-sheet-changes-us-anti-personnel-landmine-policy.

[101] Office of the Press Secretary, “Press Gaggle by Press Secretary Josh Earnest en route Joint Base Andrews, 6/27/2014,” The White House, 27 June 2014, bit.ly/WhiteHouse27June2016.

[102] This includes: Belarus, Bhutan, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Estonia, Finland, FYR Macedonia, Nigeria, Oman, Papua New Guinea, and Turkey.