Landmine Monitor 2017

Introduction

The 1997 Mine Ban Treaty was the first disarmament convention committing States Parties to provide assistance to the victims of a specific weapon. Twenty years on, what had started as a single paragraph in a treaty section on international cooperation has become much more.

At the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in 1997, Jody Williams, the co-laureate with the ICBL, announced the intention of the campaign to intensify its efforts to fortify the original, somewhat truncated, victim assistance provision:

…we would like stronger language regarding victim assistance. But, given the close cooperation with governments which resulted in the treaty itself, we are certain that these issues can be addressed through the annual meetings and review conferences provided for in the treaty.[1]

Unquestionably, based on the evidence of many years of Monitor reporting, that is what has happened. Fifteen annual Meetings of States Parties, many more intersessional meetings, regional symposia, national seminars, and three five-year review conferences have advanced and extended the development of victim assistance. Mutually-agreed objectives further manifested States Parties’ commitments, through the universally-adopted five-year action plans.

Since the emergence of victim assistance through the Mine Ban Treaty, other weapons-related conventions have adopted this rapidly emerging norm. The 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions codified the expanded principles and commitments of victim assistance into binding international law; these were introduced into the planning of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Protocol V on explosive remnants of war (ERW) in 2008, and most recently included in the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

A striking collection of objectives, action points, research findings, guidance, and recommendations of outcome documents, reports, and other publications has supported the practical implementation of activities. National government focal points were appointed, and training programs implemented to build their capacity. Above all, the work was driven by the persistent efforts of states and civil society. International, national, and local organizations worked together, including representatives of the survivors’ own networks.

The components of victim assistance include, but are not restricted to: data collection and needs assessment with referral to emergency and continuing medical care; physical rehabilitation, including prosthetics and other assistive devices; psychological support; social and economic inclusion; and the adoption or adjustment of relevant laws and public policies. Mine victims according to the accepted understanding of the term, includes survivors[2] as well as affected families and communities.[3]

The Monitor website includes detailed country profiles examining progress in victim assistance in some 70 countries, including both States Parties and states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty and the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[4]

A collection of thematic overviews, briefing papers, factsheets, and infographics related to victim assistance produced since 1999, as well as the latest key country profiles, is available through the Victim Assistance Resources portal on the Monitor website.[5]

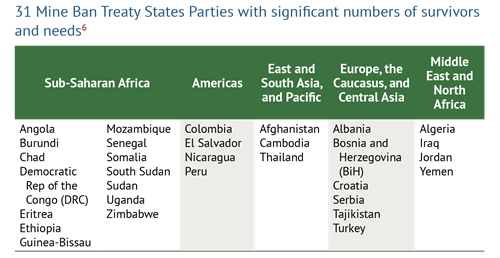

At the halfway point of the Mine Ban Treaty’s Maputo Action Plan 2014–2019, this chapter principally takes stock of the annual changes and challenges to assistance in the States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and needs. It draws from reporting on the activities and challenges of hundreds of relevant programs implemented through government agencies, international and national organizations and NGOs, survivors’ networks and similar community-based organizations, as well as other service providers.

At the Mine Ban Treaty Third Review Conference held in Maputo in 2014, States Parties formally declared that they remain very much aware of their “enduring obligations to mine victims.”[7] The actions of the Maputo Action Plan also adopted at that conference, can be summarized as follows:

- Assess the needs; evaluate the availability and gaps in services; support efforts to make referrals to existing services.

- Enhance plans, policies, and legal frameworks.

- Ensure the inclusion and full and active participation of mine victims and their representative organizations in all matters that affect them; enhance capacity.

- Increase the availability of and accessibility to services, opportunities, and social protection measures; strengthen local capacities and enhance coordination.

- Address the needs and guarantee rights in an age- and gender-sensitive manner.

- Communicate time-bound and measurable objectives annually.

- Report on measurable improvements in advance of the next review conference.

The plan also affirms the need for States Parties to continue carrying out the actions of the previous Cartagena Action Plan in order to make assistance available, affordable, accessible, and sustainable.[8]

Assessing the needs

States Parties commit to assess needs for victim assistance—including through sex- and age-disaggregated data—and gauge the availability of services required.[9] They should also use this assessment activity as an opportunity to make referrals to existing services. Most states did not report large-scale needs assessments for 2016–2017, although many collected data disaggregated by age and gender through casualty recording systems.

A project to support the demining sector in Chad started a victim identification and needs assessment survey in two pilot regions in September 2016, to be completed in 2018. In Cambodia, the Quality of Life Survey continued reaching survivors and persons with disabilities in mine-affected and areas of the country. In Albania, a socio-economic and medical needs assessment of marginalized ERW victims was conducted in three phases from 2013 through 2016, which included referrals and useful information for further planning. The victim assistance department of Yemen’s mine action program screened more than 4,000 survivors in 2016, more than 10% of whom received some direct support.

In most countries where NGO services providers operated, they made efforts to understand the needs of beneficiaries or affected populations as well as the barriers that they face in accessing services. However, this information was not always shared widely and, in some cases, due to a lack of capacity to store or process the information in the relevant ministries’ departments, did not reach national mechanisms. Mine action operators that collected information on casualties sometimes also provided referrals or direct support to survivors.

Frameworks For Assistance

The Maputo Action Plan calls for activities addressing the specific needs of victims and also emphasizes the need to simultaneously integrate victim assistance into other frameworks including disability, health, social welfare, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction.[10] It also recognizes that in addition to integrating victim assistance, States Parties need to, in actual fact, “ensure that broader frameworks are reaching mine victims.”

Many of these frameworks have their own representative international administrations, guidance documents, plans, and objectives that may also be reflected in national-level activities that can reach survivors, families, and communities. (For more information about national legal frameworks and new laws, see the section at the end of this chapter.)

The following frameworks are among those that have particular relevance to the implementation of victim assistance actions:

United Nations coordinated approach to victim assistance

Within the UN system, an expanded UN Policy on Victim Assistance in Mine Action adopted in 2016 “intends to generate a renewed impetus and commitment from the United Nations in support of mine and ERW victims.”[11]

World Health Organization plans and guidance

The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Disability Action Plan 2014–2021 was developed and revised with broad input, including a joint contribution by ICBL members and participating survivor networks. The plan reflects many of the most important concerns raised by survivor networks, such as ensuring access to rehabilitation in rural and remote areas, as well as participation and inclusion.

In 2017, the WHO recommendations on health-related rehabilitation were released. They comprise a 2030 perspective linked to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The WHO also has a comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. In addition, although less recently, the WHO community-based rehabilitation (CBR) guidelines were promoted among victim assistance actors from States Parties.[12]

Humanitarian disarmament settings

In November 2016, on the margins of the Mine Ban Treaty Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties, the Coordinators on Victim Assistance, and the Coordinators on Cooperation and Assistance of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, together with the Mine Ban Treaty Victim Assistance Committee, launched guidance publications. These were, respectively: the “Guidance on an Integrated Approach to Victim Assistance: by States for States,” undertaken with technical support from Handicap International;[13] and the “Guidance on Victim Assistance Reporting,” developed with a technical expert on victim assistance, that applies to commitments made by States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and the Convention on Conventional Weapons Protocol V.[14]

Also, at the Fifteenth Meeting of States Parties, the delegation of Italy proposed to have the Convention on Cluster Munitions coordinators’ guidance on an “Integrated Approach to Victim Assistance” mentioned in the meeting’s final report document. Some debate over the appropriateness of the reference to the Convention on Cluster Munitions followed. Subsequently, the final report included a mention of the ultimately synergistic goals of the collaboration between the treaty-machinery victim assistance coordination bodies:[15]

The Meeting also took note of the conclusions of the Committee on Victim Assistance, with particular reference to encouraging the exchange of information and experiences, where applicable, regarding how victim assistance is dealt with under different conventions.[16]

Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are highly complementary to the aims of victim assistance under the Mine Ban Treaty, and they offer opportunities for bridging between relevant frameworks. The SDGs, a set of 17 aspirational goals with corresponding targets and indicators that all UN member states are expected to use to frame policies and stimulate action for positive change in 2015–2030, are designed to address the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development. Their emphasis is on reaching the most marginalized persons, commonly phrased as “leaving no-one behind.”[17]

Transitional justice mechanisms and reparations funds

In many post-conflict countries, national mechanisms to compensate or assist victims of armed conflict are a major source of support that can benefit survivors and their families and communities. Governments have established transitional justice mechanisms to provide compensation and benefits. The Monitor has identified states with war reparations mechanisms or similar legislation that are reported to provide assistance by various means to mine/ERW victims among other conflict victims. These include Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Chile, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Nicaragua, Serbia, and Turkey. Chile is a new addition to this list as in 2017, after a years-long process, it adopted legislation to provide reparations for mine/ERW survivors.

Similarly, specific international funding for conflict victims can also benefit mine/ERW survivors and other victims. For example, in northern Uganda the International Criminal Court’s Trust Fund for Victims (VTF) supports health and rehabilitation activities for conflict victims, including mine/ERW survivors. In Afghanistan, the Third Afghan Civilian Assistance Program (ACAP III) provides targeted immediate assistance to victims of conflict—including mines/ERW—, strengthens existing services, and contributes to the development of national authorities’ capabilities to provide assistance to civilian victims of conflict.

Rights of persons with disabilities

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is the international human rights legal instrument that has been most discussed in relation to the implementation of victim assistance. Victim assistance is often included in international and national CRPD coordination structures of countries that are party to both the Mine Ban Treaty and the CRPD. State reporting under the CRPD has sometimes also mentioned victim assistance and landmine survivors.[18] Only five States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant numbers of survivors are not party to the CRPD: Chad is a signatory, while Eritrea, Somalia, South Sudan, and Tajikistan have not signed the CRPD.

In progressive orientation toward disability rights-based assistance by international actors, in early 2017, the ICRC’s Special Fund for the Disabled (created in 1983) became the MoveAbility Foundation. With increased international attention on issues of disability attributable to the CRPD, the change reflects the international organization’s broader adjusted operational orientation since 2014, which is specifically inclusive of the needs of all persons with disabilities.[19]

Conflict and humanitarian emergencies

In 2016–2017, activities continued to raise awareness of, or improve, responses to the needs and rights of persons with disabilities in armed conflicts and fragile situations that could potentially benefit mine survivors and their communities.

The charter on the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities into Humanitarian Action was adopted at the World Humanitarian Summit in Turkey in May 2016.[20] An Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Task Team on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action was established in 2016 to develop and adopt implementation guidelines by the end of 2018. Co-chairs are from UNICEF, the International Disability Alliance, and Handicap International. They lead a large task team consisting of 48 individuals from 35 various organizations, including many that are involved in victim assistance or contribute to the wellbeing and rights of survivors.[21]

Two States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and ongoing conflict, Iraq and Yemen, had a Level-3 IASC system-wide response activated in 2016–2017. Such an activation occurs when a humanitarian situation suddenly and significantly changes and it is clear that the existing capacity to coordinate and deliver humanitarian assistance and protection does not match the scale, complexity, and urgency of the crisis.[22]

Other States Parties where conflict and unstable security situations impacted implementation of victim assistance included Afghanistan, DRC, South Sudan, Somalia, and Turkey.

Regional mechanisms for the rights of persons with disabilities

The Maputo Action Plan highlights regional opportunities for the fulfillment of relevant actions. Also, it affirms that each state will take into account “its own local, national and regional circumstances.”[23] Regional mechanisms for the rights of persons with disabilities are among the relevant instruments providing such opportunities, but to date few States Parties have made the connection in their reporting on victim assistance. These mechanisms include the following:[24]

- Continental Plan of Action for the African Decade of Persons with Disabilities 2010–2019.

- Asian and Pacific Decade of Persons with Disabilities for the period 2013 to 2022 and its implementing framework with indicators, the Incheon Strategy to “Make the Right Real” for Persons with Disabilities in Asia and the Pacific.

- Inter-American Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities.

- Council of Europe Strategy on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities—Human Rights: A Reality for All 2017–2023.

Enhancing plans and policies

At the national level and within the community of the Mine Ban Treaty, the Maputo Action Plan provides a framework that allows States Parties to make qualitative assessments of progress in victim assistance. It calls for activities addressing the specific needs of victims, while integrating victim assistance into other frameworks by incorporating relevant actions into the appropriate sectors. These include disability, health, social welfare, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction.[25] States Parties commit to addressing victim assistance objectives “with the same precision and intensity as for other aims of the Convention.”[26]

States Parties committed to have time-bound and measurable objectives to implement national policies and plans that will tangibly contribute to the main goals of victim assistance.[27] In 2016, 13 of the 31 States Parties had victim assistance or relevant disability plans in place, and another two had draft plans.[28] In 2016–2017, broad disability plans with relevance to mine/ERW survivors were adopted in Albania and BiH.

In 2016, 20 of the 31 States Parties had active victim assistance coordination mechanisms or disability coordination mechanisms that considered the issues relating to the needs of mine/ERW survivors.[29] Coordination of victim assistance in BiH restarted and a new coordination mechanism was adopted through the national mine action center in Turkey.

Among the States Parties with active victim assistance coordination in 2016, most active national coordination mechanisms either collaborated with,[30] or were included as part of,[31] a disability coordination mechanism.

Inclusion and active participation of mine victims

States Parties should ensure the “full and active participation of mine victims and their representative organizations in all matters that affect them.”[32] In 2016, survivors and their representative organizations, including survivor networks and disabled persons’ organizations, participated in coordination activities in at least 17 of the 20 States Parties with active mechanisms.[33] In Colombia, after years of advocacy, landmine survivors won the right to join in Victim’s Participation Roundtables (VPRs) as a specific category of victims, thus ensuring them a spot at each table at all community levels.

Availability of and Accessibility to Services

States Parties committed to “increase availability of and accessibility to appropriate comprehensive rehabilitation services, economic inclusion opportunities and social protection measures…including expanding quality services in rural and remote areas and paying particular attention to vulnerable groups.”[34] The following changes, progress, and challenges were reported for 2016 in the 31 States Parties with significant numbers of survivors and needs:

Medical care

Medical care services for mine/ERW survivors were strengthened in some countries in the Sub-Saharan Africa region, including in Burundi, Chad, and Mozambique. However, access to medical care remained limited in the DRC, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, and Zimbabwe, with survivors having to travel long distances in order to access services, or being unable to access primary healthcare services at all. In Somalia, ongoing conflict damaged health facilities and continued to weaken an already fragile health system. In Sudan and South Sudan, emergency healthcare services were mainly provided by international organizations and NGOs.

In Afghanistan, where ongoing conflict resulted in continued high-demand for medical care, there were fewer resources available for mine/ERW survivors in 2016 compared with 2015.

In Croatia, cooperation between a pharmacy and a national foundation resulted in the donation of products for treating the health problems of people affected by mines/ERW.

Some healthcare services for persons with disabilities were available in Iraq, but have decreased over time. International organizations continued to provide much needed assistance in conflict affected areas. In Yemen, health facilities were damaged and the ongoing conflict further weakened the health system.

Rehabilitation including prosthetics

Sustained efforts to improve the availability of physical rehabilitation services were reported in Burundi, Guinea-Bissau, Eritrea, South Sudan, and Sudan. Shortage of raw materials and financial resources were an obstacle to the development of the physical rehabilitation sector in Angola, Senegal, and Zimbabwe. Moreover, such services were often only available in major cities. Survivors in Angola, Chad, DRC, Guinea-Bissau, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Senegal, and Zimbabwe struggled to access physical rehabilitation and orthopedic services because the number of facilities providing these services were limited, and sometimes costly. Ongoing conflict and insecurity also hindered access to rehabilitation services in the DRC and Somalia.

In Afghanistan, three new physical rehabilitation centers were established in as many provinces, however at least seven more such centers were still planned and needed. Authorities also acknowledged that it would be unrealistic to consider the government capable of ensuring the required rehabilitation services itself. Due to a severe funding problem, physical rehabilitation was significantly reduced at centers run by an NGO in two provinces. In Cambodia, a national NGO was forced to stop providing services including wheelchairs and assistive devices due a lack of funding and donor constraints from July 2015 through May 2016, and production was severely reduced throughout 2016. A draft curriculum for a physiotherapy school was developed. No significant progress in aligning rehabilitation reporting systems or handover of centers to government management was reported, but such plans were developed and adjusted.

In Albania, the quality of services provided at the National Prosthetic Center remained inadequate, creating greater demand at the rehabilitation center in the area where most survivors live. In BiH and Serbia, while provision of orthopedic devices is mandated by law, associated regulations were not adequately enforced thus limiting access. In Croatia, few changes were identified in the availability of or access to services and programs by mine/ERW survivors. In Tajikistan, the renovation of the branch of the national prosthetics center in a mine-affected region was completed.

The coverage of physiotherapy care was extended through home visits in El Salvador, while in Nicaragua the health ministry hired additional technicians for the national rehabilitation center and satellite centers. A critical situation for prostheses supply in Colombia was reported, with access through the state health system taking between one year and one-and-a-half years, while in rural areas inadequate availability and quality of prosthesis sometimes resulted in health complications for survivors.

In Algeria, mine/ERW survivors and other persons with disabilities continued to have access to most prosthetic and assistive devices free-of-charge. Iraq increased the capacity-building of physiotherapists, but fewer prostheses were provided to mine/ERW survivors in 2016 than in 2015. In Yemen, material support to physical rehabilitation centers increased to respond to higher demand. The availability of rehabilitation increased in Jordan.

Socio-economic inclusion

Projects to encourage the economic inclusion of survivors were rare and under-resourced in Angola, Ethiopia, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, and Uganda. In 2016, socio-economic inclusion activities decreased sharply in Senegal and South Sudan, and were nearly nonexistent in Somalia. In Zimbabwe, only 15% of the population was engaged in formal employment, which drastically limited opportunities for persons with disabilities. Some economic and social inclusion programs were reported in Burundi, Chad, DRC, Guinea-Bissau, Ethiopia, Senegal, South Sudan, and Sudan. In Burundi, the program included a range of levers, such as occupational training, microloans, membership of a community mutual support group, and business start-up kits. In Guinea-Bissau, there was an emphasis on social inclusion through sports. Vocational training programs were implemented in Ethiopia, Senegal, South Sudan, and Sudan.

In Albania, some NGO-led economic and social inclusion programs were reported, however governmental social services agencies were often unable to implement them due to a lack of funding. The number of available economic inclusion activities and beneficiaries declined rapidly in BiH.

In Iraq, there was a lack of statistics on access by persons with disabilities to work opportunities, but the Ministry of Labor provided some flexible low-interest loans for conflict survivors. Socio-economic inclusion activities were nearly nonexistent in Yemen, where livelihood activities by the survivor network stopped due to lack of funding.

Education

In 2016–2017, inclusive education programs were being implemented in Algeria, Burundi, Chad, DRC, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Zimbabwe. However, despite ongoing efforts, the Ministry of Education of DRC estimated that it was educating too few children with disabilities. The education systems in Eritrea and Mozambique were not inclusive, with separate schools for children with disabilities, while school buildings in Mozambique were inaccessible to persons with disabilities. In Guinea-Bissau, civil society noted that persons with disabilities experienced neglect in their community and throughout the education system.

Psychosocial support

The provision of psychosocial services increased in 2016 in DRC and Eritrea. In Eritrea in particular, these services were deployed to four regions that had previously not been reached. Psychological support however remained one of the biggest challenges in mine/ERW victim assistance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Such services were extremely limited, or non-existent, in Angola, DRC, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. There was a decrease in the availability of psychosocial services in Mozambique and Senegal.

Afghanistan and Cambodia required planning and structures to make available psychosocial support, including making peer support more available and sustainable.

In Colombia, peer support would have to be recognized formally in the universal health coverage system in order for survivors’ organizations to access resources for implementation through universal coverage, as they do with other victim assistance-related services.

Psychological support remained among the most serious needs of survivors in Albania. One survivors’ organization in BiH continued to integrate peer support provided by survivors themselves into government-run services. No significant changes were reported for Croatia, where it was previously found that social, psychological, and peer support remained neglected areas of rehabilitation.

The availability of psychological support and follow-up trauma care in Iraq, including for internally displaced persons, was inadequate to meet needs. In Yemen, international NGOs increased mental health and psychosocial support activities across the country in response to massive trauma and the increasing need for services.

Guaranteeing rights in an age- and gender-sensitive manner

The Maputo Action Plan speaks of “the imperative to address the needs and guarantee the rights of mine victims, in an age- and gender-sensitive manner.”[35]

Gender considerations

While men and boys are the majority of reported casualties, women and girls may be disproportionally disadvantaged as a result of mine/ERW incidents and suffer multiple forms of discrimination as survivors. To guide a rights-based approach to victim assistance for women and girls, States Parties can apply the principles of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).[36] Implementation of CEDAW by States Parties to that convention should ensure the rights of women and girls and protect them from discrimination and exploitation.[37]

In Ethiopia, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities expressed concern at the lack of inclusive education opportunities, especially for girls with disabilities. The number of projects for children with disabilities in Senegal decreased due to the unreasonable length and difficulty of administrative processes under the Committee for the Protection of the Child that now channeled funding from UNICEF. In DRC, a project was implemented that promoted the socio-economic inclusion of persons with disabilities—in particular women and girls.

Support was given to the training of health professionals in Colombia in order to raise awareness about addressing gender- and age-related needs of survivors. Increases in the limits for the granting of loans to women beneficiaries in El Salvador aimed at providing the opportunity for greater gender-sensitive development.

Afghanistan’s mine action gender mainstreaming strategy 2014–2016 upon expiry was replaced with a new mine action gender and diversity policy.

In Croatia, a project included unemployed women from mine-affected communities who were among the most marginalized, including social welfare beneficiaries living in underprivileged areas, members of ethnic minorities, women with disabilities, and survivors of domestic violence.

In Yemen, women faced additional challenges accessing medical care due to the lack of gender-sensitive services, including a lack of female rehabilitation professionals.

Age considerations

Child survivors have specific and additional needs in all aspects of assistance. In 2016 and 2017, inclusive education and age-sensitive assistance were far from adequate in most countries. In this regard, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is particularly relevant to the implementation of victim assistance with a rights-based approach.[38]

The annually updated Monitorfactsheet on the Impact of Mines/ERW on Children contains more details on issues pertaining to children, youth, and adolescents.[39]

Communicating objectives and reporting improvements

Victim assistance objectives should be updated, their implementation monitored, and progress reported annually. Each year, “plans, policies, legal frameworks” should be adapted and improved according to the States Parties’ evidence-based objectives. Budgets should also be reported.[40]

As in the previous year, more than half of the most-affected 31 States Parties included some information on victim assistance activities in their Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 reports covering calendar year 2016.[41] Eleven States Parties reported on progress and on victim assistance activities conducted during the previous year.[42] Less than half of the most-affected 31 States Parties included in their victim assistance reporting existing, or newly adopted, national policies, plans, and legal frameworks.[43] When reporting on national policies, plans, and legal frameworks, about a third of those States Parties reported on victim assistance plans, a third on disability policy, and the remaining third on both. Inclusive education was noted in some reporting, but assistance under other frameworks was not cited.

There is no detailed or specific format for reporting on victim assistance under the Mine Ban Treaty, however suggestions and guidelines have been presented over time.[44] The “Guide to Reporting”[45] submitted by the President of the Mine Ban Treaty Fourteenth Meeting of States Parties indicates that victim assistance activities, policies, and plans could be reported on a sequential form marked, G.[46] Yet, the majority of the 31 most-affected States Parties used other forms, the voluntary form J,[47] as well as F(1) and H(2) to report on victim assistance.

Although States Parties made a political commitment to communicate time-bound and measurable objectives, such objectives were almost always absent from Article 7 reports. Only Thailand reported directly on measurable national objectives. Afghanistan, Albania, Cambodia, and Croatia also reported some measurable activities that aligned with objectives. Most states that reported focused on implementation and monitoring of services rather than enhancements to plans and frameworks as called for in the Maputo Action Plan.

Legal frameworks and new laws

According to the Maputo Action Plan, States Parties collectively agree that victim assistance should be integrated into broader national policies, plans, and legal frameworks and that they will make “enhancements” to the legal frameworks in effect as a means of operationalizing the integration. Some new plans and policies were adopted in the reporting period, and several more had been drafted and were pending endorsement.

As the CRPD is implemented in Ethiopia, many new policies and guidelines have been issued to localize the provisions of the convention that also benefit mine/ERW survivors. South Sudan launched the National Disability and Inclusion Policy in 2016, which was yet to have funding allocated. The Sudan Persons with Disabilities Act 2017 was adopted and signed.

El Salvador incorporated new policies for granting credits with a gender focus and consideration of the extent of vulnerability of beneficiaries.

The process of amending discriminatory national disability legislation in Afghanistan was completed.

In Croatia, the ministry responsible for war veterans announced a new law on civilian war victims, including mine/ERW survivors. Tajikistan, which is not party to the CRPD, approved a National Program on Rehabilitation of Persons with Disabilities, covering physical rehabilitation services and social inclusion and protection.

Often the process for adopting legislation remained under review pending formal adoption for extensive time periods. In some cases, the pace of policy development was so sluggish that the strategic approaches being articulated became outdated or irrelevant before they were adopted.

The results of a 2010 survey in Angola that was intended to inform victim assistance policy were yet to be translated into programming by 2016. The application decree for the domestic law protecting the rights of persons with disabilities in Chad remained pending the president’s signature to make it a law. A proposal for a new disability rights law in DRC was drafted in 2012, but the draft had not been approved by the end of 2016. In 2011, Eritrea announced the development of a national disability policy, which remains in draft status. In 2015, Somalia announced that the prime minister had “ratified” the CRPD, however, it had not been deposited as of October 2017. Zimbabwe has ratified the CRPD, but is yet to domesticate the law or revise existing legislation accordingly.

In Nicaragua, veterans protested that the 2013 law that regulates assistance for basic necessities and socio-economic reintegration to former combatants including those with disabilities, was not implemented.

A national disability and physical rehabilitation strategic plan for the health sector for 2016–2020 in Afghanistan was drafted and in approval stages.

Regulations concerning the rights of persons with disabilities in BiH lack the legal mechanisms necessary for their actual implementation and enforcement. In Serbia, a strategy for improvement of the situation of persons with disability by 2024 had been drafted and was awaiting the view of the European Commission as of March 2017.

A review in 2016 recommended Iraq’s law on the care of persons with disabilities and special needs should be revised to ensure full compliance with the CRPD.

[1] “Jody Williams—Nobel Lecture,” Oslo, 10 December 1997, www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1997/williams-lecture.html.

[2] A “survivor” is a person who was injured by mines/ERW and lived.

[3] See, “Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009,” www.icbl.org/media/933290/Nairobi-Action-Plan-2005.pdf.

[4] Country profiles are available on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org/cp. Findings specific to victim assistance in states and other areas with victims of cluster munitions are available through Landmine Monitor 2017’s companion publication; ICBL-CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2017, bit.ly/CMM17.

[5] See, the Monitor, “Victim Assistance Resources,” www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/victim-assistance.aspx.

[6] In addition, States Parties Mali and Ukraine, both of which have had hundreds of mine/ERW casualties in the past two years, may be considered to have significant numbers of survivors with great needs for assistance that remain unreported.

[7] “MAPUTO +15,” Declaration of Mine Ban Treaty States Parties, adopted 27 June 2014, www.apminebanconvention.org/eu-council-decision/maputo-15.

[8] “Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014: Ending the Suffering Caused by Anti-Personnel Mines,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, bit.ly/MBTCartagenaPlan.

[9] Maputo Action Plan Action #12, bit.ly/MaputoActionPlan.

[10] Maputo Action Plan Actions #12 to #18.

[11] “The United Nations Policy on Victim Assistance in Mine Action (2016 Update),” undated, bit.ly/UNMineActionVA2016; and UNMAS, “Issues: Victim Assistance,” undated, www.mineaction.org/issues/victimassistance.

[12] The WHO CBR Guidelines were the subject of focused training for government victim assistance focal points at the Mine Ban Treaty Tenth Meeting of the States Parties in 2010; a victim assistance experts’ program was dedicated to their Geneva launch and training on their practical application, bit.ly/MBT10MSPVA.

[13] “Guidance on an Integrated Approach to Victim Assistance: By States for States,” 30 November 2016, www.clusterconvention.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/here.pdf.

[14] “Guidance on Victim Assistance Reporting,” undated but 2016, www.apminebanconvention.org/fileadmin/APMBC/Guidance-on-Victim-Assistance-Reporting.pdf.

[15] Australia, the Netherlands, and Belgium supported the inclusion of the text proposed by Italy, while Chile welcomed the guidance and encouraged further work between the coordinators with the objective to support victim assistance as one of the most important aims of both conventions. Brazil, Greece, and Turkey took the floor to speak against the proposal.

[16] “Final Report, Fifteenth Meeting Santiago, 28 November–1 December 2016,” APLC/MSP.15/2016/10, 14 December 2016, para. 29, bit.ly/MBTMSP15Final.

[17] Persons with disabilities are referred to directly in the SDGs: education (Goal 4), employment (Goal 8), reducing inequality (Goal 10), and accessibility of human settlements (Goal 11), in addition to including persons with disabilities in data collection and monitoring (Goal 17). With an emphasis on poverty reduction, equality, and inclusion, the SDGs also recognize the need for the “achievement of durable peace and sustainable development in countries in conflict and post-conflict situations.”

[18] The 26 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant numbers of survivors that are also States Parties to the CRPD are: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, DRC, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Sudan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

[19] ICRC, “Special Appeal 2016: Disability and Mine Action,” Geneva, December 2015, www.icrc.org/sites/default/files/topic/file_plus_list/disability_mine2016_rex2015_651_final.pdf.

[20] “Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action,” undated but 2016, http://humanitariandisabilitycharter.org/.

[21] IASC, “2017 Progress Report–IASC Task Team on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action,” 10 March 2017, bit.ly/IASCProgress17.

[22] Based on an analysis of five criteria: scale, complexity, urgency, capacity, and reputational risk. IASC, “L3 IASC System-wide response activations and deactivations,” 4 April, 2017, bit.ly/IASCL3.

[23] Maputo Action Plan Action #15.

[24] The Arab Decade of Disabled Persons (2003–2012) was not renewed.

[25] Maputo Action Plan Actions #12 to #18.

[26] “Maputo Action Plan,” Maputo, 27 June 2014, p. 3.

[27] Maputo Action Plan Action #13.

[28] Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Tajikistan, and Thailand. Algeria and Sudan had plans pending approval or formal adoption.

[29] The states with coordination mechanisms were: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH (restarted), Burundi, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Turkey (new).

[30] In Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Serbia, Sudan, Thailand, and Turkey.

[31] In Cambodia, Iraq, South Sudan, and Tajikistan.

[32] Maputo Action Plan Action #16.

[33] Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand.

[34] Maputo Action Plan Action #15.

[35] Maputo Action Plan Action #17.

[36] Of the 31 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, all except Somalia and Sudan are also States Parties to CEDAW.

[37] The Committee of CEDAW General Recommendation 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict, and post-conflict situations, and General Recommendation 27 on older women and protection of their human rights are also particularly applicable.

[38] Some of the resources on children and victim assistance include: Sebastian Kasack, Assistance to Victims of Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War: Guidance on Child-focused Victim Assistance (UNICEF, November 2014), www.mineaction.org/resources/guidance-child-focused-victim-assistance-unicef; Austria and Colombia, “Strengthening the Assistance to Child Victims,” Maputo Review Conference Documents, June 2014, www.maputoreviewconference.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC3/3RC-Austria-Colombia-Paper.pdf; and Republic of Colombia, “Guide for Comprehensive assistance to boys, girls and adolescent landmine victims – Guidelines for the constructions of plans, programmes, projects and protocols,” Bogota, 2014, bit.ly/ColombiaLandmineVA2014.

[39] These factsheets, produced since 2009, can be accessed at the Monitor, “Victim Assistance Resources,” www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/our-research/victim-assistance.aspx.

[40] Maputo Action Plan Actions #13 and #14.

[41] The States Parties that provided some updates on victim assistance were: Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, Iraq, Jordan, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, South Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. Algeria submitted identical reporting to the previous year and Burundi reported on information from 2012.

[42] Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Croatia, Iraq, Senegal, Thailand, Turkey, and Yemen reported directly on victim assistance activities and progress.

[43] The States Parties that mentioned national policies, plans and legal frameworks in their Article 7 report were: Afghanistan, Albania, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, Jordan, Peru, Serbia, South Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Zimbabwe.

[44] See, ICBL Working Group on Victim Assistance (Prepared for the Standing Committee on Victim Assistance, Socio-economic Reintegration and Mine Awareness), “Draft Suggestion for Use of Form J to Report on Victim Assistance,” December 2000, bit.ly/FormJSuggestions2000; and see the more recent Mine Ban Treaty, “Guide To Reporting,” October 2015, bit.ly/2MBTReportingGuide2015.

[45] Mine Ban Treaty, “Guide to Reporting,” October 2015, bit.ly/2MBTReportingGuide2015.

[46] Of the 31 most-affected States Parties, only Cambodia, Colombia, Thailand, and Yemen used form G to report on victim assistance activities.

[47] Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Burundi, Chad, Croatia, Iraq, Peru, and South Sudan. Mine Ban Treaty States Parties have been previously encouraged to use Form J of the Article 7 reporting format “in particular to report on assistance provided for the care and rehabilitation, and social and economic reintegration, of mine victims.” Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form J, Reporting Format.