Landmine Monitor 2020

Banning Antipersonnel Mines

Jump to a specific section of the chapter:

Banning landmines | Use | Universalization | Production | Transfers | Stockpiles | Transparency

Since it was adopted in September 1997, the Mine Ban Treaty has stigmatized antipersonnel mines through its comprehensive prohibition on use, production, transfer, and stockpiling of the weapon.

A total of 164 States Parties are applying this binding international humanitarian law treaty to ensure the clearance of mined areas within 10 years, provision of risk education for as long as the threat remains, destruction of stockpiled mines within four years, and provision of victim assistance for a lifetime.

Most of the 33 countries that remain outside of the treaty nonetheless abide by its key provisions and thus act in compliance with the international normative framework. During this reporting period, Landmine Monitor documented new use of antipersonnel mines by government forces in only one country, Myanmar, which engages with, but has not joined the Mine Ban Treaty.

Efforts to ensure the treaty’s provisions are implemented have been hindered by use of antipersonnel mines by non-state armed groups (NSAGs), particularly improvised mines.[1] NSAGs used antipersonnel mines in at least six countries during this reporting period, including in States Parties Afghanistan and Colombia, and states not party India, Libya, Myanmar, and Pakistan.

The new United States (US) policy rolling back its prohibitions on landmine production and use is one of the most significant and regrettable developments of 2020. Issued by the administration of President Donald Trump on 31 January 2020, the policy has taken the US off the path toward joining the Mine Ban Treaty, a goal most recently set during the Obama administration in 2014.[2]

In general, States Parties’ implementation of and compliance with the Mine Ban Treaty has been excellent. The core obligations have largely been respected, and compliance challenges continue to be addressed in a cooperative manner. However, some States Parties could do much more to implement key provisions of the treaty, particularly mine clearance and victim assistance, as detailed in this report and in online country profiles.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 has seen the community of States Parties, United Nations (UN) agencies, international organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), and the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), adapt their work supporting the Mine Ban Treaty. They remain strong and focused on the treaty’s ultimate objective of putting an end to the suffering and casualties caused by antipersonnel mines.

There have been no allegations of use of antipersonnel mines by States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty during the reporting period, from mid-2019 through October 2020. However, Landmine Monitor documented new use of antipersonnel mines by government forces in state not party Myanmar. Previously, Landmine Monitor 2018 and Landmine Monitor 2019 also found that government forces in Myanmar used antipersonnel mines.

Landmine Monitor identified new use of antipersonnel landmines by NSAGs in six countries during the reporting period, as listed in the table.

Locations of antipersonnel mine use mid-2019–October 2020[3]

Landmine Monitor has not documented or confirmed, during this reporting period, any use of antipersonnel mines by Syrian government forces or Russian forces participating in joint military operations in Syria. NSAGs in Syria likely continued to use improvised landmines as in previous years, but limited access by independent sources to territory under NSAG control made it difficult to confirm new use.

Landmine Monitor was also unable to document or confirm allegations of new antipersonnel mine use by NSAGs in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Egypt, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, the Philippines, Somalia, Tunisia, Turkey, or Yemen. In many cases, a lack of available information, or means to verify it, meant that it was not possible to determine if mine incidents and casualties were the result of new use of antipersonnel mines in the preceding 12-month period, due to legacy or remaining contamination of mines, including improvised mines laid in previous years, or involved some other kind of explosive device.

Landmine use by government forces

Myanmar

Since the publication of its first annual report in 1999, Landmine Monitor has every year documented the use of antipersonnel mines in Myanmar by government forces, known as the Tatmadaw, and by various NSAGs.

However, the government of Myanmar continues to deny its use of antipersonnel mines.

Since mid-2018, fighting between the Tatmadaw and the NSAG Arakan Army in Rakhine state has intensified. The Arakan Army has regularly published photographs online of antipersonnel mines produced by the Ka Pa Sa, the state-owned military industries, including MM2, MM5, and MM6 antipersonnel mines, among other seized weaponry.[4] While these photographs do not specifically identify new landmine use, they do indicate that antipersonnel mines are part of the weaponry of frontline units.

Claims of new mine use by government forces during the reporting period include:

- In September 2020, a villager from Hpo Kaung Chaung village in Buthidaung township, Rakhine state, stepped on a landmine while collecting firewood from the site of a temporary Tatmadaw camp which had been vacated earlier in 2020.[5]

- In June 2020, a villager in western Hpapun township, Kayin state, was killed by a landmine laid by the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) near a Tatmadaw post. The mine had been laid due to an increase in tensions between the KNLA and the Tatmadaw.[6]

- In May 2020, villagers in northern Hpapun township, Kayin state, alleged that Tatmadaw soldiers from Infantry Battalion 19 and Light Infantry Battalions 434, 341, and 340, operating under the Hpapun Operations Command, emplaced mines at the eastern part of their battalion’s base along a major road.[7]

- On 7 January 2020, near Teik Tu Pauk village in Kyauk Yan village tract, in Rakhine state’s Buthidaung township, several children and an adult were killed or injured by mines the villagers indicated had been laid by the Tatmadaw. Previously, the Tatmadaw had made a temporary camp and left chopped dried bushes from the area they cleared. A teacher and his students went to the area to find firewood. The villagers stated that soldiers did not warn them that mines had been laid by government forces around the temporary camp. Once they began to collect branches they stepped on mines, killing four and injuring three.[8]

- In November 2019, the Shan State Army-South (SSA-S) published photographs of MM2 antipersonnel mines which they claimed had been laid by the Tatmadaw’s Brigade 99 near Wan Wah village of the Murng Mu region of Namtu township, in northern Shan state. They alleged that after clashes between the Tatmadaw and other ethnic armed groups, the Tatmadaw began to emplace landmines on farmland outside the villages and near the woods where they thought rebel groups would be injured by them.[9]

It is often difficult to ascribe specific responsibility for incidents to a particular combatant group in Myanmar, however in every month during early 2020 villagers reported landmine casualties in areas where armed conflict had only recently occurred. Examples of such incidents include:

- On 29 February, 11 March, and 5 May 2020, landmine incidents caused injuries to villagers in areas near Ah Lae Sakhan village in Ye Phyu township, in the Tanintharyi region.[10]

- On 19 January 2020, a villager was injured in an area where Tatmadaw and Arakan Army forces had clashed in Ponnagyun township, Rakhine state, but the perpetrator could not be determined.[11]

These are among the latest in a string of casualties which began in October 2018 in an area under dispute between the Karen National Union and the New Mon State Party, both NSAG signatories to the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement, signed in 2015 between the government and eight NSAGs. Two more NSAGs signed in 2018. Both parties have denied using landmines but have accused each other of doing so. Local activists have informed the Monitor that the following incidents also involved improvised mines, but were unable to attribute responsibility for use:

- On 30 July 2020, one child was killed and five were injured in Kho Tin village, Kutkai township, Shan state, after finding a landmine and playing with it. Villagers said that Tatmadaw soldiers had previously stayed in the house where the incident occurred.[12]

- On 14 July 2020, an abbot of a Buddhist monastery in Namkham township, Shan state, was killed when he triggered an antipersonnel landmine while cleaning the grounds. Villagers said Tatmadaw soldiers had frequently stayed in the monastery grounds but that the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) also was based in the area. Villagers called on both groups to remove their mines from the area.[13]

- On 24 May 2020, one villager was injured by a mine, and a second was injured while coming to his aid in an area where conflict between the Tatmadaw and Arakan Army had occurred in Ponnagyun township, Rakhine state, but villagers did not know who laid the mine.[14]

- On 5 April 2020, a villager in Motesoe Chaung village in Rathedaung township, Rakhine state, was killed by a landmine in an area where clashes between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army were a frequent occurrence.[15]

- In March 2020, two villagers were killed by a landmine near Kham Sar village in Kyaukme township, northern Shan state. Armed conflict between the Tatmadaw, the SSA-S and the (TNLA) had previously occurred in the area and it is uncertain which group may have been responsible.[16]

At the Fourth Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty in November 2019, which was attended by delegations from both Myanmar and neighbor Bangladesh, Myanmar’s representative neither confirmed nor denied mine use, but stated, “Building lasting peace is the most fundamental and important task in the process of stopping future use of anti-personnel mines.”[17]

Bangladesh called on Myanmar to impose a moratorium on the use, production and transfer of antipersonnel mines. Bangladesh reiterated its “deep concern” over Myanmar’s continued mine use and said that its “border management authorities recorded anti-personnel mine related accidents within Myanmar territory along our borders even as recently as in September and November 2019, leading to several civilian fatalities and injuries.”[18]

Myanmar’s observer delegation made no comment on Bangladesh’s offer of assistance or its suggestion of a moratorium on use, as Myanmar’s delegation had left the room by the time the statement was made.

Landmine casualties continue to be reported in Rakhine state, on the Myanmar side of the border with Bangladesh. On 16 March 2020, a Rohingya refugee living in a refugee camp on the border was killed while collecting firewood in the “no man’s land” between Maungdaw township adjacent to Bandarban district.[19]

Landmine use by NSAGs

In the reporting period, Landmine Monitor identified new use of antipersonnel mines by NSAGs in Afghanistan, Colombia, India, Libya, Myanmar, and Pakistan.

Afghanistan

NSAG use of improvised mines in Afghanistan in 2019 and 2020 resulted in numerous casualties.[20] The use of improvised mines in Afghanistan is primarily attributed to the Taliban and Islamic State Khorasan Province. According to the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), “anti-government” forces used victim-activated improvised mines in slightly decreasing numbers throughout 2019 and in the first half of 2020.[21]

Colombia

The Colombian government reported landmine use in 2019 and 2020 by residual or dissident forces of both the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) and the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN). Colombia reported 508 new mine incidents in 2019.[22] Local media has reported numerous landmine seizure incidents in late 2019 and early 2020.[23]

India

Maoist insurgents in India have made sporadic use of improvised landmines. In August 2020, two Adivasis (tribal people) were killed after they stepped on a mine laid by the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army (PLGA) of the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-M) in Visakhapatnam district, in Andhra Pradesh.[24] The CPI-M admitted responsibility for the incident to the family and by audio press note to the village where it occurred, claiming that they had laid the booby-trap for pursuing police forces.[25] Prior to that, in December 2019, a Central Reserve Police Force officer was injured when he stepped on a mine allegedly laid by the CPI-M near Lohardaga in Jharkhand state. In the same area the previous day, a girl was killed by a landmine and five others were injured while visiting a waterfall.[26] In August 2019, in Kanker,Chhattisgarh state, a villager herding cattle was killed after stepping on a landmine allegedly laid by the CPI-M. Previously, in July 2017, the Deputy Inspector General of Police in Chhattisgarh state told the state news agency, “Pressure IEDs planted randomly inside the forests in unpredictable places, where frequent de-mining operations are not feasible, remain a challenge.”[27]

Libya

In May 2020, the United Nations-recognized Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) discovered significant mine contamination in areas of Tripoli vacated by rebels that month. The departing rebels were from a Russian government-linked military company, the Wagner group, which was fighting on behalf of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, commander of the Tobruk-based Libyan National Army. Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported, “GNA-aligned forces shared photographs on Twitter on May 29 showing four types of antipersonnel landmines manufactured in the Soviet Union or Russia and claiming they were ‘laid by the Wagner mercenaries,’ in the Ain Zara, Al-Khilla, Salahuddin, Sidra, and Wadi al-Rabi districts of Tripoli. Other photographs shared on social media show mines equipped with tripwires and mines used as triggers to detonate larger improvised explosive devices. Video footage shows various explosive charges used to booby trap homes, including antivehicle mines, paired with various types of fuzes and a mix of electronic timers, circuit boards, and modified cell phones.”[28]

The new use was condemned by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL),[29] by the President of the Eighteenth Meeting of States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty Ambassador Osman Abufatima Adam Mohammed,[30] and by the ICBL.[31] The mines, both standard and improvised, caused casualties among civilians returning to the area. By early July 2020, UNSMIL reported 138 casualties including from clearance of the newly laid explosive devices.[32]

The antipersonnel mines discovered in Tripoli in May were of Soviet and Russian origin and included POM-2, PMN-2, and olive drab-colored MON-50 mines that were not previously recorded in Libya, suggesting these landmines may have been transferred into the country in recent years.[33]

Myanmar

Many NSAGs have used antipersonnel mines in Myanmar since 1999. In late 2019 and early 2020, there were allegations of new use by the Arakan Army, the KNLA and other groups.[34]

It is often difficult to ascribe responsibility for each mine incident to a specific armed group. For example, in August 2019, in northern Shan state, the Tatmadaw engaged in armed conflict with three members of the Northern Alliance—the TNLA, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Arakan Army—near Maw Harn village in Kutkai township. Subsequently, a resident of Maw Harn was injured by a landmine. The villagers said there had been no landmines in the area prior to the conflict, but did not know which group was responsible for using them.[35]

Several allegations of recent use were also reported in Kayin state:

- In March–April 2020, the KNLA’s Third Company used mines in Hpapun township during armed conflict with the Tatmadaw, which led to the injury of a villager in May 2020.[36]

- In late 2019, soldiers of KNLA Headquarters emplaced mines in Hpapun township to halt work on the controversial Hatgyi Dam on the Salween River, resulting in injury of a local villager in February 2020.[37]

- In July 2019, in Hpapun township, the Karen National Defence Organization (KNDO) laid mines in the Bu Ah Der village tract reportedly to defend against attack by the Tatmadaw.[38]

- In May 2019, in Hlaingbwe township, a Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA) officer from Meh Pru village tract ordered his soldiers to plant more landmines in seven nearby mountainous villages to protect their area.[39]

Pakistan

NSAGs in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa used improvised antipersonnel landmines during the reporting period. Use is attributed to a variety of militant groups, frequently referred to as “miscreants” in local media reports, but generally accepted to be constituent groups of the Tehrik-i-Taliban in Pakistan (TTP) and Balochi insurgent groups.[40] In April 2020, a spokesman for the Baloch Liberation Army claimed responsibility for mines laid near a Pakistani Army post in the Kalgari mountains in Kohistan Marri, causing death and injury to two soldiers.[41] As in previous years, many military personnel and some civilians were killed or injured in incidents of new mine use, however, from available information it is difficult to attribute specific responsibility in each case.[42] Landmine Monitor has recorded numerous antipersonnel mine incidents in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, although in some cases the precise date of mine use cannot be ascertained.

Universalizing the Landmine Ban

Since the Mine Ban Treaty entered into force on 1 March 1999, states wishing to join can no longer sign and ratify the treaty but must instead accede, a process that essentially combines signature and ratification. Of the 164 States Parties, 132 signed and ratified the treaty, while 32 acceded.[43]

No states joined the Mine Ban Treaty in the reporting period. The last states to accede to the treaty were Sri Lanka and the State of Palestine, both in December 2017.

The 33 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty include the Marshall Islands, which is the last signatory yet to ratify.

Annual UN General Assembly resolution

Since 1997, an annual United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolution has provided states outside the Mine Ban Treaty with an important opportunity to demonstrate their support for the humanitarian rationale of the treaty and the objective of its universalization. More than a dozen countries have acceded to the Mine Ban Treaty after voting in favor of consecutive UNGA resolutions.[44]

On 12 December 2019, UNGA Resolution 74/61, calling for the universalization and full implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty, was adopted by a vote of 169 in favor, none against, and 18 abstentions.[45] This marked the second consecutive year of 169 votes in favor, and represented a slight increase in the number of abstentions (up from 16 in 2018). States not party Egypt, Iran, Myanmar, Pakistan, Singapore, and South Korea made statements explaining their votes.

A core of 14 states not party have abstained from consecutive Mine Ban Treaty resolutions since 1997: Cuba, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, Syria, the US, Uzbekistan,[46] and Vietnam.[47]

Change in US Landmine Policy

The US landmine policy announced on 31 January 2020 allows the US to develop, produce, and use landmines[48] as long as they are “non-persistent,” that is, equipped with self-destruct and self-deactivation features.[49] The policy abandons the previous constraint on using antipersonnel mines only on the Korean Peninsula, and instead permits the US to use them anywhere in the world.[50]

A Department of Defense fact sheet issued with the policy, entitled “Strategic Advantages of Landmines,” asserts that landmines are “a vital tool in conventional warfare” that provide “a necessary warfighting capability…while reducing the risk of unintended harm to non-combatants.” Frequently Asked Questions prepared by the Department of Defense for the policy announcement assert that the US needs landmines now, because “the strategic environment has changed” since 2014 with “the return of Great Power Competition and a focus on near-peer competitors” or adversaries. Defense officials announcing the policy told media they could envision the US using landmines in a variety of theaters against a range of adversaries, such as Russia and China.[51]

The Trump administration’s decision to reverse US prohibitions and limits on landmines has been widely condemned and criticized, including by the US Campaign to Ban Landmines (USCBL). Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont said it “reverses the gains we have made and weakens our global leadership.”[52] On 6 May 2020, Leahy, Representative Jim McGovern and more than 100 other members of Congress wrote to Secretary of Defense Mark Esper expressing disappointment at the policy reversal, regret at the lack of consultation, and providing three pages of questions regarding future plans for development and use of antipersonnel mines.[53] The Department of Defense provided a detailed 12-page response in September 2020.

Department of Defense officials have said the US does not intend to pressure partners and allies to change their landmine policies, nor will the new US policy prevent it from conducting future operations in coalition with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and other partners.

Mine Ban Treaty President, Ambassador Osman Abufatima Adam Mohammed of Sudan, issued a statement asserting that the policy “goes against” the “long-standing commitment” made by the US to help eradicate the suffering caused by landmines. States Parties including Austria, Belgium,[54] France, Germany,[55] the Netherlands,[56] Norway,[57] and Switzerland[58] expressed their concern and disappointment over the new US policy, as did the European Union.[59] In addition to the ICBL and the ICRC, other civil society actors that decried the policy change included several US Senators, Lloyd Axworthy (former Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) USA, and the US Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Non-state armed groups

Some NSAGs have committed to observe the ban on antipersonnel mines, which reflects the strength of the growing international norm and stigmatization of the weapon. In September 2019, the Central Division, a faction of the Syrian National Army, and in July 2019, the Southern Transitional Council in Yemen, agreed to a ban on use of landmines by signing the Geneva Call Deed of Commitment.[60] At least 70 NSAGs have committed to halt using antipersonnel mines since 1997.[61] The exact number is difficult to determine, as NSAGs have no permanence, frequently split into factions, go out of existence, or become part of state structures.

Production of Antipersonnel Mines

More than 50 states produced antipersonnel mines at some point in the past.[62] Forty states have ceased production of antipersonnel mines, including three that are not party to the Mine Ban Treaty: Egypt, Israel, and Nepal.[63]

The Monitor identifies 12 states as producers of antipersonnel mines, an increase of one from last year’s report: China, Cuba, India, Iran, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, the US, and Vietnam. Most of these countries are not believed to be actively producing mines but have yet to disavow ever doing so.[64] Those most likely to be actively producing are India, Iran, Myanmar, and Pakistan.

The new US landmine policy returns the US to the list of countries worldwide that either actively produce antipersonnel landmines or reserve the right to do so.[65] According to the Department of Defense, the 2020 policy “encourages the Military Departments to explore acquiring landmines…that could further reduce the risk of unintended harm to non-combatants.”[66] Yet, US defense officials commenting on the new policy told media that as the US has sufficient inventory of so-called smart landmines, there is no need to restart production immediately. No antipersonnel mines or other victim-activated munitions are being funded in the fiscal year 2021 ammunition procurement budgets of the US Armed Services or Defense Department.[67]

As of August 2020, Iran’s Ministry of Defence Export Center advertised the availability of the YM-IV, a bounding, fragmentation antipersonnel mine, and the YM-I-S, a self-neutralizing antipersonnel blast mine.[68]

In August 2019, South Korea informed the ICBL that it had not produced any antipersonnel landmines in the previous five years.[69] Until South Korea renounces future production, it remains listed as a producer of antipersonnel mines.

Production of antipersonnel mines by India appears to be ongoing into 2020. Purchase order records retrieved from a publicly accessible online government procurement database list private companies providing component parts for APER-1B antipersonnel mines to Indian Ordnance Factories, a state-owned enterprise, into June 2020.[70] Previously, in September 2018, Indian military officials told the Monitor that the final assembly of complete mines remains under the exclusive control of Indian Ordnance Factories.[71] In the previous two years, components were produced under these contracts and supplied to the Ammunition Factory Khadki, in Maharashtra state.[72]

NSAGs have produced improvised landmines in Afghanistan, Colombia, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Yemen.[73] Antipersonnel mines are prohibited regardless of whether they were assembled in a factory or improvised from locally available materials.

Transfers of Antipersonnel Mines

A de facto global ban on the transfer of antipersonnel mines has been in effect since the mid-1990s. This ban is attributable to the mine ban movement and the stigma created by the Mine Ban Treaty. Landmine Monitor has never conclusively documented any state-to-state transfers of antipersonnel mines since it began publishing annually in 1999.

At least nine states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty have enacted formal moratoriums on the export of antipersonnel mines: China, India, Israel, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, and the US. Other past exporters have made statements declaring that they have stopped exporting, including Cuba and Vietnam. Iran also claims to have stopped exporting in 1997, despite evidence to the contrary.[74]

Stockpiled Antipersonnel Mines

States not party

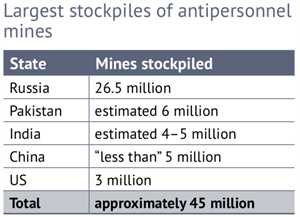

The Monitor estimates that as many as 30 of the 33 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty stockpile antipersonnel landmines.[75] In 1999, the Monitor estimated that, collectively, states not party stockpiled about 160 million antipersonnel mines, but today the global collective total may be less than 50 million.[76]

It is unclear if all 30 states are currently stockpiling antipersonnel mines. Officials from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have provided contradictory information regarding its possession of stocks, while Bahrain and Morocco have stated that they possess only small stockpiles which are used solely for training purposes in clearance and detection techniques.

States not party to the Mine Ban Treaty routinely destroy stockpiled antipersonnel mines as an element of ammunition management programs and the phasing out of obsolete munitions. In recent years, such stockpile destruction has been reported in China, Israel, Mongolia, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, the US, and Vietnam.

Stockpile Destruction by Mine Ban Treaty States Parties

At least 160 of the 164 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty do not stockpile antipersonnel mines. This includes 93 states that have officially declared completion of stockpile destruction and 67 states that have declared they never possessed antipersonnel mines (except in some cases for training in detection and clearance techniques).

Collectively, States Parties have destroyed more than 55 million stockpiled antipersonnel mines, including more than 269,000 destroyed in 2019 (Greece destroyed 53,039 and Ukraine destroyed 216,291).

Three States Parties possess a collective total of almost four million antipersonnel mines left to destroy: Ukraine (3.3 million), Greece (343,413), and Sri Lanka (62,510).

Sri Lanka declared a significant stockpile of antipersonnel mines in November 2018 when it submitted its initial Article 7 transparency report. Its deadline for completion of destruction is 1 June 2022, but Sri Lanka has stated its intent to complete stockpile destruction by the end of 2020.[77] Sri Lanka reported that the destruction of 57,033 antipersonnel mines had occurred prior to November 2018, for a total stockpile prior to destruction of 134,898 antipersonnel mines. In its May 2019 Article 7 report, Sri Lanka declared the destruction of 15,355 antipersonnel mines since its initial report.[78] As of 15 October 2020, Sri Lanka had not submitted an updated Article 7 report for calendar year 2019.

Greece and Ukraine remain in violation of Article 4 after failing to complete the destruction of their stockpiles by their four-year deadline.[79] Neither state has indicated when the obligation to destroy its remaining stockpiles will be completed. The Oslo Action Plan adopted at the Mine Ban Treaty’s Fourth Review Conference in 2020 urges states that have failed to meet their stockpile destruction deadlines to “present a time-bound plan for completion and urgently proceed with implementation as soon as possible in a transparent manner.”[80]

State Party Tuvalu must provide an initial Article 7 transparency report for the treaty, to formally confirm that it does not possess stockpiled antipersonnel mines.[81]

Mines Retained for Training and Research (Article 3)

Article 3 of the Mine Ban Treaty allows a State Party to retain or transfer “a number of anti-personnel mines for the development of and training in mine detection, mine clearance, or mine destruction techniques…The amount of such mines shall not exceed the minimum number absolutely necessary for the above-mentioned purposes.”

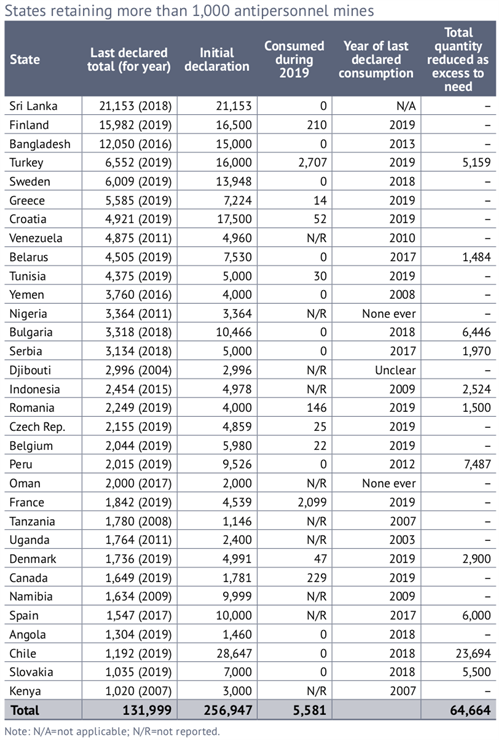

A total of 64 States Parties have reported that they retain antipersonnel mines for training and research purposes, of which 29 retain more than 1,000 mines and three (Sri Lanka, Finland, and Bangladesh) each retain more than 12,000 mines. Ninety-eight States Parties have declared that they do not retain any antipersonnel mines, including 40 states that had stockpiled antipersonnel mines in the past.[82]

In addition to those listed above, another 32 States Parties each retain fewer than 1,000 mines and together possess a total of 13,758 retained mines.[83]

Botswana, Brazil, and Uruguay all reported in 2020 that they destroyed their remaining retained mines (1,002, 364, and 260, respectively) during calendar year 2019.

The ICBL has expressed concern at the large number of States Parties that are retaining mines but apparently not using those mines for permitted purposes. For these States Parties, the number of mines retained remains the same each year, indicating none are being consumed (destroyed) during training or research activities. No other details have been provided about how the mines are being used. A total of seven States Parties have never reported consuming any mines retained for the permitted purposes since the treaty entered into force for them: Djibouti, Nigeria, and Oman (which each retain more than 1,000 mines); and Burundi, Cape Verde, Senegal, and Togo (which each retain less than 1,000 mines).

The Oslo Action Plan calls for any State Party that retains antipersonnel mines under Article 3 to “annually review the number of mines retained to ensure that they do not exceed the minimum number absolutely necessary for permitted purposes” and to “destroy all anti-personnel mines that exceed that number.”[84]

Additionally, States Parties agreed to Action #49, wherein the treaty’s president is given a new role to play in ensuring compliance with Article 3. This has been described by some as an “early warning mechanism.” The action point states, “If no information on implementing the relevant obligations [of Articles 3, 4, or 5] for two consecutive years is provided, the President will assist and engage with the States Parties concerned….”[85]

While laudable in terms of transparency, several States Parties still report retaining antipersonnel mines and devices that are fuzeless, inert, rendered free from explosives, or otherwise irrevocably rendered incapable of functioning as an antipersonnel mine, including by the destruction of the fuzes. Technically, these are no longer considered antipersonnel mines as defined by the Mine Ban Treaty. At least 13 States Parties retain antipersonnel mines in this condition.[86]

Article 7 of the Mine Ban Treaty requires that each State Party “report to the Secretary General of the United Nations as soon as practicable, and in any event not later than 180 days after the entry into force of this Convention for that State Party” regarding steps taken to implement the treaty. Thereafter, States Parties are obligated to report annually, by 30 April, on the preceding calendar year.

Tuvalu is the only State Party that has not provided an initial transparency report, after missing its 28 August 2012 deadline.

As of 15 October 2020, 46% of States Parties had submitted their annual Article 7 reports for calendar year 2019.[87] A total of 89 States Parties have not submitted a report for calendar year 2019, of which most have failed to provide an annual transparency report for two or more years.[88]

Nigeria, Yemen, and other states with recent allegations or confirmed reports of use of improvised landmines by NSAGs have failed to provide information on new contamination in their annually updated Article 7 reports.

Morocco, a state not party, submitted voluntary transparency reports from 2017–2020 (as well as in 2006, 2008–2011, and 2013). In previous years, Azerbaijan (2008–2009), Lao PDR (2010), Mongolia (2007), Palestine (2012–2013), and Sri Lanka (2005) submitted voluntary Article 7 reports.

In 2019, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic submitted a voluntary Article 7 report, covering the period from June 2014 to November 2019, and which included information on contamination and clearance as well as casualties and victim assistance in Western Sahara.

[1] The Mine Ban Treaty defines an antipersonnel landmine as “a mine designed to be exploded by the presence, proximity or contact of a person and that will incapacitate, injure or kill one or more persons.” Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) or booby-traps that are victim-activated fall under this definition regardless of how they were manufactured. The Monitor frequently uses the term “improvised landmine” to refer to victim-activated IEDs.

[2] The White House, ‘‘Statement from the Press Secretary – National Security & Defense,’’ 31 January 2020, bit.ly/WhiteHouseStatement31Jan2020; and US Department of Defense, “Memorandum: DoD Policy on Landmines,” 31 January 2020, bit.ly/DoDLandminesPolicy31Jan2020.

[3] NSAGs used mines in at least six countries in 2018–2019, eight countries in 2017–2018, nine countries in 2016–2017, 10 countries in 2015–2016 and 2014–2015, seven countries in 2013–2014, eight countries in 2012–2013, six countries in 2011–2012, four countries in 2010, six countries in 2009, seven countries in 2008, and nine countries in 2007. In the reporting period, there were also reports of NSAG use of antivehicle mines in Afghanistan, Iraq, Mali, Niger, Pakistan, the Philippines, Ukraine, and Yemen.

[4] See, Mine Free Myanmar, “Allegedly Seized Mines Displayed by Arakan Army,” 18 April 2019, bit.ly/MineFreeMyanmar18April2019. See also, allegation and photographs published on a Facebook page associated with the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS), 3 December 2019, bit.ly/FacebookRCSS3Dec2019.

[5] Monitor interview with villagers who requested anonymity.

[6] “Karen Human Rights Group Submission to Landmine Monitor,” August 2020, unpublished. The villager who eventually died from his injuries stated that he knew the placement of the mines as he had been informed by the KNLA, however forgot about them on his return to the area.

[7] “Karen Human Rights Group Submission to Landmine Monitor,” August 2020, unpublished. The villagers stated that the Tatmadaw had issued verbal warnings to avoid the area.

[8] Monitor interview with villagers who requested anonymity. Families of each of the injured were required to pay MMK20,000 (US$20) per day to the hospital so that the injured would be cared for by the doctors and nurses.

[9] Allegation and photographs published on a Facebook page associated with the RCSS, 3 December 2019, bit.ly/FacebookRCSS3Dec2019.

[10] “Two villagers from Ye Phyu Township severely wounded in landmine blasts,” Mon News Agency/Burma News International, 14 March 2020, bit.ly/MonNewsAgency14March2020; Lawi Weng, “Civilian Injured by Landmine as Mon, Karen Armed Groups Trade Blame,” The Irrawaddy, 5 May 2020, bit.ly/Irrawaddy5May2020; and Landmine Monitor interviews with informants who wished to remain anonymous.

[11] “9 people wounded in Arakan landmine explosions,” Narinjara News, 20 January 2020, bit.ly/NarinjaraNews20Jan2020.

[12] “One Child Dead and Five Injured in Northern Shan State Landmine Blast,” Network Media Group/Burma News International, 4 August 2020, bit.ly/NetworkMediaGroup4Aug2020.

[13] “Buddhist Abbot And Villager Killed By Landmine,” Shan Herald News Agency/Burma News International, 17 July 2020, bit.ly/ShanHeraldAgency17July2020.

[14] “Mro ethnic villagers Injured in Ponna Kyaut landmine blasts,” Narinjara News, 25 May 2020, bit.ly/NarinjaraNews25May2020.

[15] ‘‘Rathedaung man killed by landmine,’’ Development Media Group/Burma News International, 9 April 2020, bit.ly/DevelopmentMediaGroup9April2020.

[16] Lawi Weng, “Landmine Kills Two Shan Civilians in Northern Myanmar,” The Irrawaddy, 12 March 2020, bit.ly/TheIrrawaddy12March2020.

[17] Statement of Myanmar, Mine Ban Treaty Fourth Review Conference, segment on Universalization, Oslo, 26 November 2019, bit.ly/MyanmarStatementRevCon2019.

[18] Statement of Bangladesh, Mine Ban Treaty Fourth Review Conference, Oslo, 27 November 2019, bit.ly/BangladeshStatementRevCon2019.

[19] Abdul Azeez, ‘‘Rohingya man killed in landmine explosion,’’ Dhaka Tribune, 18 March 2020, bit.ly/DhakaTribune18March2020.

[20] Afghanistan stated that new use of improvised mines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) was responsible for killing approximately 1,451 civilians between June 2019 and May 2020. Presentation by Afghanistan, Mine Ban Treaty intersessional meetings (virtual), 1 July 2020, bit.ly/AfghanistanPresentation2020.

[21] UNAMA, “Afghanistan: Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict Annual Report 2019,” February 2020, p. 42, bit.ly/AfghanistanReportUNAMA2020.

[22] The figures were collated by Descontamina, the Colombian government agency responsible for humanitarian demining activities, which is part of the High Commission for Peace. Information provided by Maicol Velasquez, Office of the High Commissioner for Peace Information Management Team, from the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) database, 31 August 2020.

[23] See, for example, antipersonnel landmines seized from the ELN in April 2020, “En El Tambo, Cauca, un muerto y un capturado del Eln dejan operaciones militares,” (“In El Tambo, Cauca, one dead and one captured during military operations against ELN”), Extra, 28 April 2020, bit.ly/Extra28April2020. In March 2020, the army captured 120 antipersonnel landmines from a warehouse belonging to a dissident FARC faction, “Hallan depósito ilegal con material explosivo en Guaviare,” (“Illegal deposit with explosive material found in Guaviare”), RCN Radio, 17 March 2020, bit.ly/RCNRadio17March2020. In February 2020, the army found a cache of 117 antipersonnel landmines belonging to the ELN, “Hallan minas antipersonal y bandera del ELN en Guática Risaralda, zona límite con Caldas” (‘‘Antipersonnel mines and ELN flag found in Guática Risaralda, border area with Caldas’’), W Radio, 7 February 2020, bit.ly/WRadio7February2020. In October 2019, the army reportedly discovered 100 antipersonnel landmines belonging to a dissident faction of the FARC, “Hallaron 100 minas antipersona y material explosivo de las disidencias de las Farc avaluado en $50 millones,” (“100 antipersonnel mines and explosive material from FARC dissidents and valued at $50 million were found”),Minuto 30, 16 October 2019, bit.ly/Minuto16October2019.

[24] Srinivasa Rao Apparasu, “Maoist landmine kills two tribals in forest area of Visakhapatnam” Hindustan Times, 3 August 2020, bit.ly/HindustanTimes3Aug2020. See also, previous incidents: “Landmine blast near polling centre in Naxal-affected Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli,” India Today, 11 April 2019, bit.ly/IndiaToday11April2019; “Army officer defuses landmine in J-K’s Rajouri, second one kills him,” Hindustan Times, 16 February 2019, bit.ly/Hindustan-Times16Feb2019; “Maoists trigger landmine blast in Odisha, 2 SOG jawans injured,” The Times of India, 12 May 2019, bit.ly/TimesOfIndia12May2019; “Landmine kills at least 15 police in western India,” Reuters, 1 May 2019, bit.ly/Reuters1May2019; “Army man injured in landmine blast in J&K’s Poonch district,” India TV, 7 June 2019, bit.ly/IndiaTV7June2019; “One civilian killed in landmine blast,” Hans News Service, 1 April 2019, bit.ly/HansNewsService1April2019; and “Police unearth four landmines in Visakhapatnam,” The Times of India, 30 May 2019, bit.ly/TimesOfIndia30May2019.

[25] Siva G., “Andhra Pradesh: Maoists offer apologies for landmine blast,” The Times of India, 11 August 2020, bit.ly/TimesOfIndia11Aug2010.

[26] “CRPF jawan injured in land mine blast in Lohardaga,” United News of India, 25 December 2019, bit.ly/UnitedNewsofIndia25Dec2019; and “One killed, five injured in landmine blast in Jharkhand,” Telangana Today, 24 December 2019, bit.ly/TelanganaToday24Dec2019.

[27] Tikeshwar Patel, “IEDs pose huge challenge in efforts to counter Naxals: police,” Press Trust of India, 24 July 2017, bit.ly/PressTrustofIndia24July2017.

[28] HRW, “Libya: Landmines Left After Armed Group Withdraws,” 3 June 2020, bit.ly/LibyaHRW3June2020.

[29] UNSMIL press release, “UNSMIL condemns the use of Improvised Explosive Devices against the civilians in Ain Zara and Salahuddin in Tripoli,” 25 May 2020, bit.ly/UNSMIL25May2020.

[30] Anti-personnel Landmine Ban Convention press release, “Convention President condemns reported use of mines; calls for an immediate cessation of their use,” 1 June 2020, bit.ly/MBTPressRelease1June2020.

[31] ICBL, “ICBL Joins Mine Ban Partners in Condemning Reported New Mine Use in Libya,” 4 June 2020, bit.ly/LibyaICBL4June2020.

[32] UNSMIL, “Statement by Acting SRSG Stephanie Williams on the Death of Two Libyan Mine Clearance Workers in Southern Tripoli,” 6 July 2020, bit.ly/UNSMILStatement6July2020.

[33] HRW, “Libya: Landmines Left After Armed Group Withdraws,” 3 June 2020, bit.ly/LibyaHRW30June2020.

[34] There are also allegations of use by the TNLA, the Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North (SSPP/SSA-N) and the RCSS/SSA-S in their operations against the Tatmadaw during the reporting period.

[35] “Kutkai Villager ‘Seriously Injured’ by Landmine,” Shan Herald Agency for News/Burma News International, 20 September 2019, bit.ly/ShanHeraldAgency20Sept2019.

[36] “Karen Human Rights Group Submission to Landmine Monitor,” August 2020, unpublished. The villager who was injured while collecting thatch near the area stated he was aware that the KNLA had laid landmines but thought it was safe as he had collected thatch there before.

[37] “Karen Human Rights Group Submission to Landmine Monitor,” August 2020, unpublished. The villager who was injured while hunting near the area stated he was aware of verbal warnings issued by the KNLA prior to laying the landmines, but felt it was safe as he had been hunting in the area previously.

[38] “Karen Human Rights Group Submission to Landmine Monitor,” September 2019, unpublished.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Emails from Raza Shah Khan, Sustainable Peace and Development Organization (SPADO), 30 September 2019 and 21 September 2017. See also, “Landmine blasts kill five in Pakistan’s tribal areas,” Arab News, 21 August 2019, arabnews.pk/node/1543081/pakistan; “Soldier martyred, 5 injured in North Waziristan landmine blast,” Tribal News Network, 25 August 2019, bit.ly/TribalNewsNetwork25Aug2019; “At least 2 FC personnel killed, 5 injured in Kurram Agency blast,” The Nation, 10 July 2017, bit.ly/TheNation10July2017; and Ajmal Wesai, “4 children wounded in Tirinkot bomb explosion,” Pajhwok Afghan News, 5 August 2017, bit.ly/PajhwokAfghanNews5Aug2017.

[41] “Balochistan: One Pakistani soldier killed in landmine blast another wounded,” Balochwarna News, 6 April 2020, bit.ly/BalochwarnaNews6April2020.

[42] “Landmines recovered from Bajaur college,” Dawn, 22 January 2020, bit.ly/Dawn22January2020.

[43] The 32 accessions include two countries that joined the Mine Ban Treaty through the process of “succession.” These two countries are Montenegro (after the dissolution of Serbia and Montenegro) and South Sudan (after it became independent from Sudan). Of the 132 signatories, 44 ratified on or before entry into force (1 March 1999) and 88 ratified afterward.

[44] This includes Belarus, Bhutan, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Estonia, Finland, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Oman, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka, and Turkey.

[45] The 18 states that abstained were: Cuba, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Myanmar, Nepal, North Korea, Pakistan, Palau, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Syria, the US, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe.

[46] Uzbekistan voted in favor of the UNGA resolution on the Mine Ban Treaty in 1997 and did not vote on the resolution in 2018.

[47] Of these states: India, Israel, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea and the US are party to the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Amended Protocol II on landmines; Cuba and Uzbekistan are party to CCW Protocol II; Egypt and Vietnam have signed the CCW but are not party to any of its protocols. Iran, Myanmar, North Korea, and Syria remain outside any treaty-based prohibition or regulation of antipersonnel mines.

[48] The policy makes no distinction between antipersonnel and antivehicle mines, but the White House spokesperson stated that antipersonnel landmines are the focus of the new policy.

[49] The decision was outlined in a three-page policy contained in a letter signed by Secretary of Defense Mark Esper on 31 January 2020. US Department of Defense, “Memorandum: DoD Policy on Landmines,” 31 January 2020, bit.ly/DoDLandminesPolicy31Jan2020.

[50] Previous US president Barack Obama issued a new landmine policy in 2014 banning production and acquisition of antipersonnel mines as well as halting their use by the US anywhere except the Korean Peninsula. The Obama administration brought US policy further in line with the Mine Ban Treaty, but did not take any measures towards US accession. Under the 2014 policy, the US committed not to use antipersonnel landmines outside of the Korean Peninsula and not to assist, encourage, or induce other nations to use, stockpile, produce, or transfer antipersonnel mines outside of the peninsula. It also committed to no future US production or acquisition of antipersonnel mines.

[51] Jeff Seldin, “US Ends Self-Imposed Ban on Use of Landmines,” Voice of America, 31 January 2020, voanews.com/usa/us-ends-self-imposed-ban-use-landmines.

[52] Office of US Senator Patrick Leahy, “Statement on the Trump Administration’s Decision to Roll Back Limits on US Production and Use of Anti-Personnel Landmines,” 31 January 2020, bit.ly/LeahyStatementJan2020.

[53] Letter to Mark Esper, US Secretary of State, from Senator Patrick Leahy and more than 100 other Congressional representatives, 6 May 2020, bit.ly/LeahyLetterMay2020.

[54] MFA, Belgium (BelgiumMFA), “Anti-personnel mines do not make countries safe. Their use has been drastically reduced thanks to #MineBanTreaty, a cornerstone of humanitarian disarmament. We regret the new US landmine policy which is out of sync with global progress towards a mine-free world.” 4 February 2020, 18:43 UTC. Tweet. bit.ly/BelgiumMFATweet4Feb2020.

[55] Annen, Niels (NielsAnnen), “Präsident Trumps Entscheidung, das Verbot zum Einsatz von Landminen zu ignorieren, ist ein schwerer Rückschlag für die langjährigen internationalen Bemühungen, diese tödliche Waffe zu ächten. @AuswaertigesAmt @GermanyUN.” (“President Trump's decision to ignore the landmine ban is a severe blow to longstanding international efforts to outlaw this deadly weapon”). 3 February 2020, 08:34 UTC. Tweet. bit.ly/NielsAnnenTweet3Feb2020.

[56] Disarmament, NL-Amb (RobGabrielse), “The Netherlands is disheartened by the US’ decision to lift its 2014 policy on anti-personnel landmines. See also the statement by the Spokesperson of HR/VP Borrell Fontelles regarding this decision.” 4 February 2020, 19:38 UTC. Tweet. bit.ly/RobGabrielseTweet4Feb2020.

[57] MFA, Norway (NorwayMFA), “#LandMines kill and mutilate thousands of civilians every year, most of them children. Norway is a strong supporter of the @MineBanTreaty. We call upon the US to respect the ban on anti-personnel mines, and to continue to support survey and clearance of mines - FM #EriksenSoreide.” 5 February 2020, 08:34 UTC. Tweet. bit.ly/NorwayMFATweet5Feb2020.

[58] EDA-DFEA (EDA_DFAE), “La Suisse poursuit l'objectif d'un monde exempt de mines anti-personnel. C'est pourquoi le DFAE regrette l'annonce du président des Etats-Unis d'y recourir à nouveau.” (“Switzerland pursues the goal of a world free of anti-personnel mines. This is why the FDFA regrets the announcement of the President of the United States to use it again”). 7 February 2020, 14:15 UTC. Tweet. bit.ly/EDA-DFAETweet7Feb2020.

[59] European Union, “Anti-personnel mines: Statement by the Spokesperson on the United States’ decision to re-introduce their use,” 4 February 2020, bit.ly/EUStatement4Feb2020.

[60] Deed of Commitment under Geneva Call for Adherence to a Total Ban on Anti-personnel Mines and for Cooperation in Mine Action. Geneva Call press release, “Syria: the armed non-State actor “Central Division” signs Geneva Call’s Deeds of Commitment on banning anti-personnel mines and on protecting health care in armed conflict,” 12 November 2019, bit.ly/GenevaCallSyriaNov2019; and Geneva Call press release, “Yemen: The Supreme Commander of the Southern Transitional Council signs 3 Deeds of Commitment with Geneva Call to improve the protection of civilians during armed conflicts,” 2 July 2019, bit.ly/GenevaCallYemenJuly2019.

[61] As of October 2020, 48 NSAGs have committed not to use mines through the Geneva Call Deed of Commitment, 20 by self-declaration, four by the Rebel Declaration (two have signed both the Rebel Declaration and the Geneva Call Deed of Commitment), and two through a peace accord (in Nepal and Colombia). See, ICBL-CMC, Landmine Monitor, “Briefing Paper: Landmine Use by Non-State Armed Groups: A 20-Year Review,” November 2019, bit.ly/MonitorBriefingPaperNov2019.

[62] There are 51 confirmed current and past producers. Not included in that total are five States Parties that some sources have cited as past producers, but who deny it: Croatia, Nicaragua, the Philippines, Thailand, and Venezuela. It is also unclear if Syria has produced antipersonnel mines.

[63] Additionally, Taiwan passed legislation banning production in June 2006. The 36 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty that once produced antipersonnel mines are Albania, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iraq, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Uganda, the United Kingdom (UK), and Zimbabwe.

[64] For example, Singapore’s only known producer of antipersonnel landmines, Singapore Technologies Engineering, a government-linked corporation, said in November 2015 that it “is now no longer in the business of designing, producing and selling of anti-personnel mines.” PAX, ''Singapore Technologies Engineering stops production of cluster munitions,'' 19 November 2015, bit.ly/PAXSingapore19Nov2015.

[65] The 2020 policy rolls back the 2014 policy pledge to “not produce or otherwise acquire any anti-personnel munitions that are not compliant with the Ottawa Convention in the future, including to replace such munitions as they expire in the coming years.”

[66] US Department of Defense, “Memorandum: DoD Policy on Landmines,” 31 January 2020, bit.ly/DoDLandminesPolicy31Jan2020.

[67] The last time the US produced antipersonnel mines was in 1997, when it manufactured 450,000 ADAM and 13,200 CBU-89/B Gator self-destructing/self-deactivating antipersonnel mines for US$120 million. The last non-self-destruct antipersonnel mines were procured in 1990, when the US Army bought nearly 80,000 M16A1 antipersonnel mines for US$1.9 million.

[68] Ministry of Defence Export Center (MINDEX), “Bounding Mines,” undated, mindexcenter.ir/product/bounding-mines; and MINDEX, “Self Neutralized Mines,” undated, mindexcenter.ir/product/self-neutralized-mine-ym-i-s.

[69] Email to the ICBL, from Soonhee Choi, Counsellor, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Korea to the United Nations, 22 August 2019.

[70] Components for M-14 mines were tendered for Dum Dum Ordnance Factory in February and June 2020. Components for M-14 mines and AP 1B mines were tendered in June 2020 and during 2019.

[71] Landmine Monitor meeting with Cdre. Nishant Kumar, Ministry of External Affairs, and Col. Sumit Kabthiyal, Ministry of Defense, Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on lethal autonomous weapons systems, in Geneva, 27 August 2018.

[72] The following companies were listed as having concluded contracts listed for production of components of antipersonnel mines on the Indian Ordnance Factories Purchase Orders between October 2016 and November 2017: Sheth & Co., Supreme Industries Ltd., Pratap Brothers, Brahm Steel Industries, M/s Lords Vanjya Pvt. Ltd., Sandeep Metalkraft Pvt Ltd., Milan Steel, Prakash Machine Tools, Sewa Enterprises, Naveen Tools Mfg. Co. Pvt. Ltd., Shyam Udyog, and Dhruv Containers Pvt. Ltd. In addition, the following companies had established contracts for the manufacture of mine components: Ashoka Industries, Alcast, Nityanand Udyog Pvt. Ltd., Miltech Industries, Asha Industries, and Sneh Engineering Works. Mine types indicated were either M-16, M-14, APERS 1B, or “APM” mines. Indian Ordnance Factories, “Purchase Orders,” undated, bit.ly/PurchaseOrdersIOF; and Indian Ordnance Factories, “Registered Vendors,” undated, bit.ly/RegisteredVendorsIOF.

[73] Previous lists of NSAGs producing antipersonnel mines have included Iraq, Syria, Thailand, Tunisia, and Yemen.

[74] Landmine Monitor received information in 2002–2004 that demining organizations in Afghanistan were clearing and destroying many hundreds of Iranian YM-I and YM-I-B antipersonnel mines, date stamped 1999 and 2000, from abandoned Northern Alliance frontlines. Information provided to Landmine Monitor and the ICBL by HALO Trust, Danish Demining Group, and other demining groups in Afghanistan. Iranian antipersonnel and antivehicle mines were also part of a shipment seized by Israel in January 2002 off the coast of the Gaza Strip.

[75] Three states not party, all in the Pacific, have said that they do not stockpile antipersonnel mines: signatory the Marshall Islands, in addition to non-signatories Micronesia and Tonga.

[76] In 2014, China informed Landmine Monitor that its stockpile is “less than” five million, but there is a degree of uncertainty about the method China used to derive this figure. For example, it is not known whether antipersonnel mines contained in remotely-delivered systems, so-called “scatterable” mines, are counted individually or as just the container, which can hold numerous individual mines. Previously, China was estimated to have 110 million antipersonnel mines in its stockpile.

[77] Sri Lanka Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form B, November 2018, bit.ly/SriLankaArt72018.

[78] Sri Lanka Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form B, April 2019, bit.ly/SriLankaArt72019.

[79] Greece had a deadline for stockpile destruction of 1 March 2008, while Ukraine had a deadline of 1 June 2010.

[80] Oslo Action Plan, Mine Ban Treaty Fourth Review Conference, 29 November 2019, bit.ly/OsloActionPlan2019.

[81] Tuvalu has not made an official declaration, but is not thought to possess antipersonnel mines.

[82] In 2018, Argentina, Cambodia, and Ethiopia destroyed the entirety of their stockpiles retained for training and research, and the UK announced that its stockpile was comprised of inert munitions that do not fall under the scope of the treaty. Tuvalu has not submitted an initial Article 7 report, which was originally due in 2012.

[83] Zambia (907), Mali (900), Mozambique (900), the Netherlands (868), BiH (834), Honduras (826), Japan (803), Mauritania (728), Cambodia (720), Italy (617), Germany (583), South Africa (576), Sudan (528), Cyprus (500), Zimbabwe (450), Togo (436), Nicaragua (435), Portugal (383), Republic of the Congo (322), Cote d’Ivoire (290), Slovenia (272), Bhutan (211), Cape Verde (120), Eritrea (101), Gambia (100), Jordan (100), Ecuador (90), Rwanda (65), Senegal (50), Benin (30), Guinea-Bissau (9), and Burundi (4).

[84] Oslo Action Plan, Action #16, Mine Ban Treaty Fourth Review Conference, 29 November 2019, bit.ly/OsloActionPlan2019.

[85] Oslo Action Plan, Action #49, Mine Ban Treaty Fourth Review Conference, 29 November 2019, bit.ly/OsloActionPlan2019.

[86] Afghanistan, Australia, BiH, Canada, Eritrea, France, the Gambia, Germany, Lithuania, Mozambique, Senegal, Serbia, and the UK.

[87] Senegal submitted its Article 7 report in October 2020, although the report is not in the correct Article 7 format.

[88] States that have not submitted Article 7 reports for two or more years are noted in italics: Albania, Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belize, Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Comoros, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, Dominica, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Fiji, Gabon, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Iceland, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kenya, Kiribati, Kuwait, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Moldova, Mozambique, Namibia, Nauru, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Niger, Niue, North Macedonia, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Qatar, Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, São Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Tanzania, Timor-Leste, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, Vanuatu, Venezuela, and Zambia.