Landmine Monitor 2020

The Impact

Jump to a specific section of the chapter:

Contamination | Casualties | COVID-19 Impact on Mine Action | Coordination | Gender mainstreaming | Clearance | Improvised Mines | Risk Education | Victim Assistance

Introduction

This summary highlights developments and challenges in assessing and addressing the impact of mines. The first part of this overview covers contamination and casualties, while the second section focuses on land release through clearance, risk education, and victim assistance. These make up three of the five core components or “pillars” of mine action.

Reporting in this overview contributes to a baseline for developments under the Oslo Action Plan, the five-year action plan of the Mine Ban Treaty adopted in November 2019. These actions remain consistent with the fulfillment of the objectives of the treaty, whereby States Parties declare that they are:

“Determined to put an end to the suffering and casualties caused by anti-personnel mines, that kill or maim hundreds of people every week, mostly innocent and defenceless civilians and especially children, obstruct economic development and reconstruction, inhibit the repatriation of refugees and internally displaced persons, and have other severe consequences for years after emplacement.”

There are 33 States Parties that have declared having obligations under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty to clear contaminated land. Most of them reported undertaking clearance in areas under their jurisdiction and control in 2019. Three States Parties need to clarify the extent of residual contamination while five States Parties need to provide information regarding suspected or known contamination by improvised mines. Overall, high numbers of casualties due to landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) continued to be recorded in 2019, following a sharp rise in casualties due to increased conflict and contamination in 2015. The majority of new casualties were reported in States Parties to the treaty that also experience contamination by mines of an improvised nature. In 2019, 28 States Parties were known to have provided risk education to populations affected by antipersonnel mine contamination. At least 34 States Parties have responsibility for significant numbers of mine victims—these States Parties have “the greatest responsibility to act, but also the greatest needs and expectations for assistance.” Many indicated improvements in the accessibility, quality, or quantity of services for victims, but significant challenges remained in all states.

Antipersonnel mine contamination in States Parties

Under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty, States Parties are required to clear all antipersonnel mines as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the treaty.

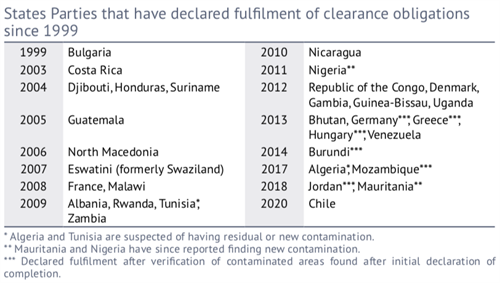

In early 2020, Chile became the latest State Party to declare completion of clearance of all mined areas in its territory,[1] an achievement that will be formally announced at the Eighteenth Meeting of States Parties in November 2020. Jordan, which had originally declared completion in 2012, completed verification and clearance of areas that had not been cleared to a humanitarian standard in 2018.[2]

No State Party declared completion of clearance in 2019. Since the Mine Ban Treaty came into force in 1999, of the 63 States Parties that reported mined areas under their jurisdiction and control, 32 States Parties have reported clearance of all antipersonnel mines from their territory.

State Party El Salvador completed clearance in 1994, before the treaty came into force.

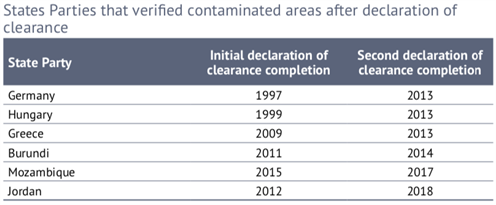

Several States Parties that have declared themselves free of antipersonnel mines later discovered previously unknown mine contamination, or were required to verify that areas had been cleared to humanitarian standards.[3] Burundi, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Jordan, and Mozambique all finally declared fulfilment of Article 5 obligations several years after their initial declarations.

Mauritania, which declared itself free of mines in 2018, but reported finding new contamination in 2019 and submitted a request for an extension of its Article 5 deadline in 2020. Nigeria announced it had fulfilled its obligation under Article 5 in 2011, but indicated newly-mined areas in 2019. It was expected to submit an Article 7 report and an Article 5 extension request in 2020.

States Parties with Article 5 obligations

As of 15 October 2020, a total of 33 States Parties have declared an identified threat of antipersonnel mine contamination on territory under their jurisdiction or control and therefore have obligations under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty.

States Parties suspected of having contamination

Several States Parties that have not declared obligations under Article 5, may have residual or newly discovered mine contamination which needs to be reported and clarified.

Residual contamination

Algeria declared fulfilment of its Article 5 obligations in 2017, but continues to find and destroy antipersonnel mines. In 2019, Algeria reported that 4,499 “isolated” mines were cleared and destroyed, a huge increase from the 188 mines found in 2018.[4] In total, 5,150 mines were reported cleared and destroyed during 2016–2019. Given the large number of mines found in 2019, Algeria needs to provide clarification to States Parties on whether the mines being found constitute contaminated areas rather than isolated residual contamination.

There have been several mine/explosive remnants of war (ERW) casualties reported in Kuwait since 1990. In 2018, there were reports of torrential rain having unearthed landmines in the country, presumed to be remnants of the 1991 Gulf War.[5] The mines are believed to be present mainly on the borders between Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq; areas used by shepherds for grazing animals. Kuwait has not made a formal declaration of contamination in line with its Article 5 obligations.

Nicaragua declared completion of clearance in April 2010, but has since faced a problem of residual mine/ERW contamination throughout the country. During 2018, Nicaragua reported that its contingency operations answered 13 reports made by the population, resulting in the clearance of 2,849m² and removal and destruction of 29 items of unexploded ordnance. Nicaragua confirmed that the contingency operations would continue through 2019, but no updated information has been shared.[6] In May 2020, two landmines exploded in El Bayuncun, San Fernando, in the border region with Honduras, injuring one person in the first incident and four people from a rescue party in the second.[7]

Improvised mine contamination

Several States Parties that have not declared clearance obligations under Article 5 or which do not provide regular Article 7 transparency reports, are suspected of having contamination by improvised mines. Improvised devices designed to detonate, or able to be detonated, by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person are prohibited by the Mine Ban Treaty.[8] States Parties with improvised mines have obligations under Article 5 to clear these devices and, under Article 7, to provide annual reporting on contamination and clearance.

The following States Parties need to clarify their status with regards to their Article 5 obligations.

In Burkina Faso, use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) by non-state armed groups (NSAGs) has been recorded since 2016. Pressure-operated improvised antivehicle mines have been increasingly used since 2018. In 2019, 21 civilians died and 14 were wounded by these devices. Improvised mines using pressure plates have also been recorded, with persistent armed attacks in northern and eastern regions since 2018.[9]

Cameroon originally declared that there were no mined areas under its jurisdiction and control, and its Article 5 deadline expired in 2013. However, since 2014, mines of an improvised nature have caused casualties, particularly in Cameroon’s northern districts along the border with Nigeria, as Boko Haram’s military activities have escalated.[10] The extent of contamination is not known but is believed to be small.

Mali has confirmed antivehicle mine contamination and since 2017 has experienced a significant increase in incidents caused by IEDs, including improvised mines, in the center of the country.[11] The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) reported to the Monitor that improvised mines in Mali are victim-activated by pressure tray or wire trap (see section on casualties).[12]

Nigeria declared at the Eleventh Meeting of States Parties, in November 2011, that it had cleared all known antipersonnel mines from its territory.[13] However, since 2017, there have been reports of incidents involving both civilian and military casualties from landmines and a range of other locally produced explosive devices planted by Boko Haram in the northeast of the country, particularly in Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa states.[14] In November 2019, at the Fourth Review Conference in Oslo, Nigeria stated that it intended to submit an Article 7 transparency report and an Article 5 deadline extension request in order to comply with its obligations under the Mine Ban Treaty, although it has yet to do this as of 15 October 2020.[15]

Tunisia declared completion of clearance in 2009, but there have been reports of both civilian and military casualties from landmines and improvised mines in the last five years.[16] The improvised mines causing casualties, particularly to shepherds walking their herds, are predominantly found in the mountainous areas of Tunisia’s northwest and southwest regions,[17] where militants are present and laying mines as an insurgency tactic.[18]

Extent of contamination in States Parties

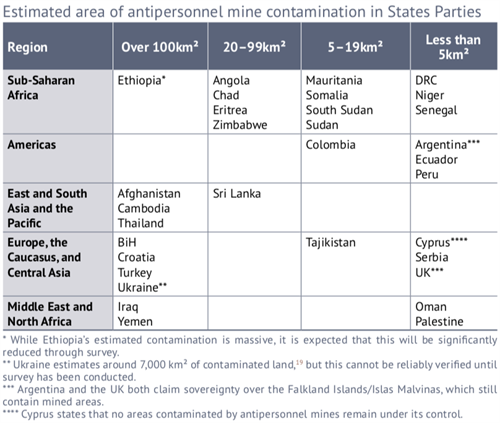

Massive antipersonnel mine contamination (defined by the ICBL-CMC as more than 100km²) is believed to exist in 10 States Parties: Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Croatia, Ethiopia, Iraq, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, and Yemen. Large contamination (20–99km²) exists in five States Parties: Angola, Chad, Eritrea, Sri Lanka, and Zimbabwe. Medium contamination (5–19km²) exists in six States Parties: Colombia, Mauritania, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Tajikistan. Less than 5km² of contamination is thought to exist in 11 States Parties: Cyprus, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ecuador, Niger, Oman, Palestine, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, and in the United Kingdom (UK) and Argentina due to their claim of sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas.

Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen have significantly over 100km2 of contamination, comprising both legacy contamination and new contamination, including improvised mines.

Iraq is dealing with contamination by improvised mines in areas liberated from the Islamic State. Iraq reported 1,239.17km² of antipersonnel mine contamination at the end of 2019, and an additional 627.58km² of contamination by improvised mines.[20]

Yemen currently has no clear understanding of the size of its contamination as the ongoing conflict continues to add to the extent and complexity of contamination.[21] Landmines that were not part of Yemeni stockpiles have reportedly been laid recently,[22] while previously cleared areas, such as Aden, have been re-contaminated.[23] The most recent estimate of contamination, from March 2017, was 323km².[24]

Afghanistan reported contamination of 191km² at the end of 2019, of which 136km² is classified as confirmed hazardous area (CHA) and 55km² as suspected hazardous area (SHA).[25] Afghanistan told the Monitor that new contamination resulting from fighting between the government and NSAGs is adding to the extent of contamination to be addressed.[26]

Cambodia and Thailand still need to verify the extent of contamination along border areas where access has been problematic due to a lack of border demarcation.[27] Cambodia estimates 817km², which includes both CHA and SHA which are not yet differentiated on the database of the Cambodian Mine Action Authority (CMAA).[28] Thailand reports 218.19km², of which 14.55km² are CHA and 203.64km² are SHA.[29]

Turkey’s contamination of 150.41km² is found along its borders with Armenia, Iran, Iraq, and Syria.[30] Turkey also has responsibility for the clearance of landmines in areas under its control in Northern Cyprus; although its most recent Article 5 extension request, submitted in 2013, did not include a timeline for clearance of mines there.[31]

BiH has also not defined the full extent of contamination although it has been undertaking a country assessment project since 2018, funded by the European Union (EU).[32] In its revised Article 5 extension request, submitted in August 2020, BiH reports contamination of 966.68km².[33]

At the end of 2019, eight of Croatia’s 21 counties were still mine-affected.[34] Croatia reported to the Monitor that more than 98% of the remaining contaminated land is in forest areas.[35]

Ukraine has reported 7,000km² of contaminated land,[36] but this cannot be reliably verified until survey has been conducted.

Ethiopia, in its Article 7 report for calendar year 2019, reported that 330.28km² had been released through technical survey and non-technical survey (NTS).[37] It is expected that the current figure of remaining contamination (over 10,000km²) will be significantly reduced through survey.[38]

Sub-Saharan Africa has a number of States Parties with heavy contamination of between 20–99km². These are Angola, Chad, Eritrea, and Zimbabwe. Sri Lanka also has less than 100km² of reported contamination.

In 2019, Angola completed non-technical survey in all 18 provinces of the country, defining 1,073 confirmed minefields, and 94 suspected minefields which are estimated at 90km² in total.[39]

Chad has about 93.3km2 of contamination, of which 93.27km2 are CHA and0.05km2 SHA.[40] This includes 2.93km² of improvised mine contamination.

Eritrea has not reported on the extent of its contamination since 2013, when it was estimated at 33.5km².[41]

Zimbabwe’s minefields on its border with Mozambique, and an inland minefield in Matebeleland North province, were reported to cover a combined total area of 42.69km² at the end of 2019.[42]

Sri Lanka reported 24km² of contaminated land as of April 2019.[43] The majority of this area was confirmed as minefields (22.42 km²).

Colombia, Mauritania, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Tajikistan are each believed to have less than 19km² of mine contamination.

Colombia’s mine contamination comprises 8.2km², of which 3.3km² are in the process of being cleared, and a projected 4.9km² of suspected contamination which has not yet been surveyed.[44] However, this does not include 166 municipalities that are inaccessible due to insecurity, where no survey or clearance has been able to take place. Contamination in Colombia also includes improvised mines.

Mauritania had previously declared clearance of all known contaminated areas in 2018, but has since identified further contaminated areas, approximately 8km², a legacy of the 1976–1978 Western Sahara conflict.[45] However, Mauritania needs to confirm whether this contamination is actually on its territory.

Somalia reported that at the end of 2019 it had 6.09km² of contaminated land,[46] but it has also reported an increase in the use of improvised mines.[47]

South Sudan, Sudan, and Tajikistan all have a relatively clear understanding of the extent of their remaining contamination, at 13.27km², 7.37km², and 11.95km² respectively.[48]

States Parties Cyprus, the DRC, Ecuador, Niger, Senegal, Serbia, Oman, Palestine, Peru, and the UK all have less than 5km² of contamination. However, some of the contamination is in areas that are contentious or difficult to access, as follows.

Cyprus reports no antipersonnel mines remaining in minefields laid by the National Guard that are on territory under its effective control.[49] Remaining contamination is in the buffer zone and areas of Turkish-controlled Northern Cyprus.[50]

The contamination in the DRC is small, but partly located in Ituri and North-Kivu provinces which are difficult to access due to the presence of NSAGs and the Ebola epidemic.[51]

In Palestine, clearance in the West Bank is constrained by political factors, including the lack of authorization granted by Israel for Palestine to conduct mine clearance operations.

Antipersonnel mine contamination in states not party and other areas

In addition to the 33 States Parties contaminated by antipersonnel mines, there are also 22 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty and five other areas that have, or are believed to have, land contaminated by antipersonnel mines on their territories.

State not party Nepal and other area Taiwan have completed clearance of known mined areas since 1999.

Extent of contamination in states not party and other areas

Mines are known or suspected to be located along the borders of several states not party, including Armenia, China, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco, North Korea, South Korea, and Uzebkistan, although the extent of contamination is not known.

The extent of contamination is known in Azerbaijan, Georgia, Israel, and Lebanon; although in Azerbaijan significant contamination also exists in the areas that are not under government control, particularly in the regions of Nagorno-Karabakh and Nakhchivan.[52] The outbreak of hostilities in Nagorno-Karabakh in late September 2020 had added further complexity to the political dynamics in the region, and is resulting in new ERW contamination, including cluster munitions.[53]

Ongoing conflict, insecurity, and the impact of improvised mines affect states not party Egypt, India, Libya, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Syria.

States not party Lao PDR and Lebanon are both party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and have prioritized clearance of cluster munition remnants. The mine contamination in Lao PDR has had little human impact, although clearance operators reported mine contamination in their areas of operation in 2019.[54] In Vietnam, the mine problem is also small compared to its ERW problem, although the full extent of mine contamination is not known.

The extent of mine contamination in China, Cuba, Iran, and Russia is unknown.

Five other areas unable to accede to the Mine Ban Treaty due to their political status are known to have mine contamination.

In Abkhazia, which had been declared free of landmine contamination in 2011,[55] The HALO Trust identified five previously unknown minefields from June–December 2019, amounting to aproximately 9,600m².[56]

Kosovo, which completed a socioeconomic baseline of the impact of ERW in 2018 to support the prioritization of remaining contamination, has 35 affected areas totaling 1.35km².[57]

The HALO Trust, the only operator in Nagorno-Karabakh, has been undertaking a baseline survey of the territory to establish the extent of contamination. A total of 9km² has been identified.[58] Further progress will be dependent on the outcome of hostilities which erupted in September 2020.

As of August 2020, Somaliland had 6.71km² of CHA across ten districts.[59] In Western Sahara, there are 15 known remaining minefields east of the Berm,[60] covering a total area of 95.8km².[61]

Landmines of all types, including antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, and improvised mines, as well as cluster munition remnants[62] and other explosive remnants of war (ERW)—henceforth mines/ERW—remain a significant threat and continue to cause indiscriminate harm.

Mine/ERW casualties in 2019

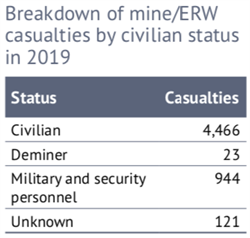

At least 5,554people were killed or injured by mines/ERW in calendar year 2019. Of that total, at least 2,170were killed, and another 3,357 were injured, while in the case of 27 casualties it was not known if the victim survived.[63] Casualties were recorded in 50 countries and five other areas. The 2019 total represents a decline from 6,897 casualties of mines/ERW in 2018, and a reduction in casualties over the past three years. Previously, a sharp rise in casualties was recorded due to increased conflict and contamination in 2015, peaking in 2016, when 9,439 casualties were recorded.[64] The significant upsurge in recorded casualties since 2014 is primarily due to large numbers of casualties in relatively few countries with intensive armed conflicts, involving the large-scale use of improvised mines.

In 2019, more than two-thirds of all casualties (3,647, or 66%) were reported in States Parties. Thus, the impact in terms of casualties caused by mines/ERW in States Parties alone was still greater in 2019 than in 2013—the year with the lowest annual number of casualties recorded globally since 1999, when 3,457 people were killed and injured in all countries and areas.

Civilians represented the majority of mine/ERW casualties compared to military and security forces,[65] continuing the well-established trend of civilian harm that influenced the adoption of the Mine Ban Treaty: 80% of casualties were civilians in 2019, where the status was known.

Child casualties are recorded where the age of the victim is less than 18 years at the time of the mine/ERW explosion, or when the casualty was reported by the source (such as media) as being a child. There were at least 1,562 child casualties in 2019, accounting for 35% of all casualties for whom the age group was known (4,508); this made up 43% of civilian casualties for whom the age group was known (3,598). Children were killed (580) or injured (979) by mines/ERW in 34 states and one other area in 2019.[66] As in previous years, in 2019, the vast majority of child casualties where the sex was known were boys (82%).[67] ERW was the device type that caused the most child casualties (758, or 49%), followed by improvised mines (576, or 37%).

In 2019, men and boys made up the majority of casualties, accounting for 85% of all casualties for whom the sex was known (3,190 of 3,759). Women and girls made up 15% of all casualties for whom the sex was known (569).

In 2019, the Monitor identified 23 casualties among deminers in nine countries (including 17 men and two women, and four for whom the sex was not recorded).[68] Another eight casualties were state military, police or other security personnel who were killed or injured while clearing, disarming, or dismantling mines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs).[69] There were two informal village deminer casualties in Cambodia in 2019. These were not included in the annual total of deminer casualties.

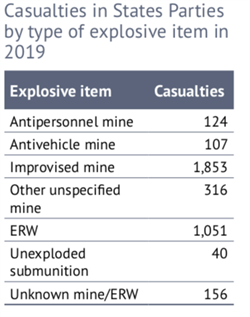

Countries with high and increasing numbers of casualties are mostly those with improvised mine casualties. For the fourth successive year, in 2019, the highest number of annual casualties was caused by improvised mines (2,994). However, the number of recorded improvised mine casualties declined significantly from 2018, which saw an all-time high of 3,789 improvised mine casualties.

Casualties in States Parties in 2019

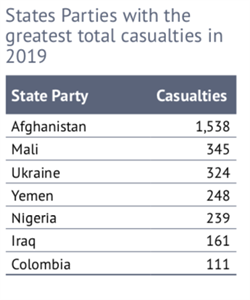

Casualties occurred in 36 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty in 2019.[70] The States Parties with over 100 recorded casualties were: Afghanistan, Colombia, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, Ukraine, and Yemen.

States Parties with high and increasing numbers of casualties were those with improvised mine casualties. Collectively, States Parties recorded only 26% of the commercially-manufactured antipersonnel mine casualties reported in 2019 (124). States Parties accounted for 62% (1,853) of improvised mine casualties and 74% (316) of casualties from undefined landmine types that, in the context of media reporting terminology, are also likely to be mines of an improvised nature.

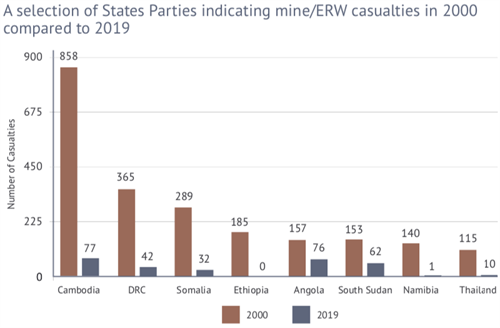

There is a clear overall trend of declining annual casualties in most States Parties over the 20 years since the Mine Ban Treaty came into existence. This trend is particularly evident in most of the countries which reported the highest casualty figures after the treaty entered into force in 1999.

Declining casualty rates have also been recorded over time in Colombia, from a peak of 1,228 casualties in 2006 to 111 casualties in 2019. However, casualties in 2018 and 2019 increased, having dropped below 100 in the preceding two years after the peace agreement took effect. Relatively new State Party Sri Lanka had 223 mine/ERW casualties in 2000 and two in 2019.

It is certain that there are additional casualties each year that are not captured in the Monitor’s global mine/ERW casualty statistics, with most occurring in severely affected countries and those experiencing conflict. In some states and areas, many casualties go unrecorded, meaning the true casualty figure is likely significantly higher in those countries.

In Afghanistan, data collection was affected by ongoing conflict. The existing data collection system records only civilians, and the reporting of military casualties was generally rare. Since May 2017, the Afghan military has stopped releasing its conflict casualty figures entirely.

In Iraq, as in previous years, it is certain that there were many more mine/ERW casualties that occurred in 2019 that were not identified. However, United Nations (UN) reporting indicates that there has been a significant overall reduction in conflict-related casualties of all types since 2018 and decided to stop releasing civilian casualty updates on a monthly basis, but rather based on the circumstances.[71] Data collection in Iraq remains a challenge. In 2019 and 2020, the Information Management and Mine Action Program (iMMAP) provided regular updates on explosive hazards.[72] However, mine/ERW incident casualties were almost never reported among the victims recorded.

In 2019, a detailed report on data in Iraq by Humanity & Inclusion (HI) found that “there is limited to no coordination between the actors involved in victim and accident reporting and data management processes.”[73] The Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) and Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA) reportedly suffer from insufficient staff, lack of technical expertise, inconsistent and mismatched reporting forms and a lack of formalized guidelines on roles and responsibilities for the many different actors involved in data collection and management.

In Mali in 2019, as was the case in recent years, only vehicles were involved in mine incidents and no casualty occurred while individuals were on foot. The same was true for Burkina Faso in 2019. Five of the 233 civilian casualties recorded for Mali in 2019 occurred in incidents where they were on an animal-drawn cart, compared to 25 in 2018. Those improvised mines causing casualties in Mali and Burkina Faso were believed to have acted as de facto “antivehicle mines.” However, in some incidents, reporting may be unclear as to whether the improvised device involved was an unused command-detonated IED–and thus in effect an explosive remnant rather than a mine–or if it was a victim-activated improvised mine. The impact in terms of casualties is largely indistinguishable.

The ongoing conflict in Yemen prevented the effective operation of a national casualty surveillance mechanism. Yemen reported that the Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC) information management system has become outdated and is currently not usable. Furthermore, the conflict has presented new mines and mine technologies (improvised mines), with which YEMAC has had no previous experience. This is compounded by the scale of the conflict and its extensive impact across the country.[74]

In Yemen, the Monitor recorded 248 casualties for 2019. The Civilian Impact Monitoring Project (CIMP) recorded 233 landmine casualties in Yemen, with just under half due to incidents involving civilian vehicles: “Landmines accounted for highest number of casualties in incidents impacting on civilian vehicles, with 36 landmine incidents resulting in 114 casualties; 41% of the total.”[75] In May 2019, Yemen reported having collected data on 820 victims and injured persons since the beginning of 2019.[76] In its Article 7 report for calendar year 2019, Yemen reported 1,050 victims surveyed in 2019. Previous data indicates that aggregate annual casualty figures reported by Yemen include casualties for all time surveyed during that year, rather than casualties which occurred in the calendar year itself.

The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) recorded casualty data in Nigeria for calendar year 2019. From 2016–2019, data for Nigeria was initially and regularly recorded by Mines Advisory Group (MAG), which significantly heightened understanding and awareness of the extent of the impact of mines/ERW (especially improvised mines) in the country. Subsequently, Nigeria’s acknowledgement of its obligation to clear improvised mines under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty further indicated that the improvised mine casualties included those from antipersonnel types.

Casualties in states not party and other areas

The Monitor identified 1,834 mine/ERW casualties in 2019 in 14 states not party.[77] More than a thousand of the casualties were recorded in Syria (1,125), which represents a continuing decrease from 1,465 in 2018, and 40% less than the 1,906 casualties recorded in 2017.[78] However, since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011, annual totals of recorded mine/ERW casualties in the country are thought to be an undercount. Casualty totals have fluctuated in part due to inconsistent availability of data and sources.

For Syria, ambiguity in the way that casualties and explosive incidents are reported in the media often leaves it unclear whether an explosive device was command-detonated or victim-activated. Many casualties, including civilian casualties in Syria that were reported to be from mines, booby-traps, roadside bombs, or IEDs, and which were not explicitly reported as ‘targeted’, were excluded from the Monitor annual casualty dataset if the cause of activation was not adequately defined.[79] Due to the preference for conflict fatality reporting systems in situations of armed conflict, there are many more people recorded as dead compared to those recorded injured. The Monitor recorded 636 people killed and 489 people injured in Syria in 2019, whereas generally only just over a quarter of all mine/ERW casualties will be fatalities. Therefore, it is certain, based on the probable proportion of fatalities to survivors, that the actual number of casualties occurring in Syria was substantially higher than the annual total recorded.

The next highest numbers of casualties among the countries yet to join the Mine Ban Treaty were recorded in Myanmar, with 358 casualties, followed by Pakistan with 136.

Seventy-three casualties were reported in five other areas: Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Somaliland, Taiwan, and Western Sahara.

Casualty recording

It is certain that numerous casualties go unrecorded each year. Some of the most mine/ERW-affected countries, especially conflict-affected states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty, do not have functional national casualty surveillance systems in place, nor do other forms of adequate reporting exist.

The need to improve the adequacy and efficacy of data collection in mine action and conflict situations, as well as the demand for progress in related systems and mechanisms, was a key theme during the reporting period. A thematic panel discussion during the May 2019 Mine Ban Treaty intersessional meetings highlighted the need to strengthen injury surveillance systems to monitor “the physical impact of explosive ordnance” and to identify risk groups and factors. This was reflected in the text of the Oslo Action Plan.[80]

The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) undertook a process to define a set of minimum data requirements for mine action that could accompany the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) Core Geographic Information System (GIS) data. In March 2020, the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) adopted the summary of minimum data requirements, including entries for mine/ERW incidents and casualties.[81]

In September 2020, the first ever joint statement on casualty recording was delivered at the 45th session of the Human Rights Council, presented by Afghanistan, a country consistently among those with the most mine/ERW casualties in recent years. It was co-signed by 49 other states.

In 2019, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released the first UN publication on casualty recording methodology, after several years of the need being highlighted by civil society.[82] The OHCHR Guidance on Casualty Recording notes that “casualty recording has received increasing recognition as an important and effective means of enhancing the protection of civilians in armed conflict situations and elsewhere.”[83]

However, the new UN casualty reporting system does not differentiate casualties caused by antipersonnel mines or any specific explosive device type as defined by disarmament regulation contexts. According to the OHCHR standards in place to monitor the Sustainable Development Goal indicator on conflict-related deaths (16.1.2), disaggregation for the cause of death includes the broader category of “planted explosives and unexploded ordnance.”[84]

The Monitor’s casualty records include only mine/ERW casualties: people killed or injured in incidents involving explosive items detonated by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person or vehicle.[85] Casualties from incidents caused or reasonably suspected to have been caused by remotely detonated mines or IEDs—those that were not victim-activated—are not included. Mines/ERW therefore differs from the IMAS classification of explosive ordnance.[86] That is because the IMAS definition of explosive ordnance additionally includes devices that are activated manually or by remote control.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has represented an additional challenge to mine action programs activities in most affected countries, including data collection.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

COVID-19 pandemic impacts on clearance, risk education and victim assistance

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 was a challenging year for mine action and an unusual reporting period for the Landmine Monitor. Mine clearance in many countries was affected by restrictions imposed to curb the spread of the pandemic. It was reported to the Monitor that clearance operations were temporarily suspended in States Parties Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Colombia, Peru, Senegal, and Zimbabwe; states not party Armenia, Lebanon, and Vietnam; and other areas Kosovo and Western Sahara, as well as the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas.[87]

In Cambodia, clearance teams received COVID-19 prevention training. It was reported that mine clearance programs in Cambodia and Thailand were not greatly affected by the pandemic, at least in part because operations are conducted in remote areas.

Other mine action activities affected by the pandemic included activities related to resources, survey, planning, and training.

BiH reallocated €10 million (US$10.9 million)[88] of European Union (EU) funds for humanitarian demining projects to COVID-19 response and migration issues. Chile anticipated a possible need to reallocate mine action funding to respond to sanitary and social needs. A mission to Mauritania to collect additional information on contamination was delayed. Resource mobilization activities for mine action were suspended in Senegal. In Ukraine, the adoption of amendments to the Law on Mine Action was delayed. In Yemen, the development of national mine action standards was postponed, and the training of information management personnel on the use of IMSMA Core was deferred. Several national mine action centers anticipated delays in their operational calendars, including delays which may impact their clearance completion date.[89] In some countries, mine action and risk education teams were repurposed to deliver hygiene products and COVID-19 prevention messages. The HALO Trust mobilized its vehicle fleet and workforce in 21 countries and four other areas to deliver medical and sanitation supplies.[90]

Risk education programs have been greatly impacted by the pandemic and related restrictions, but have also been an area where efforts to combine mine action and a COVID-19 response are most significant. An important proportion of risk education programs are based on face-to-face sessions, which are often considered the most appropriate way to reach affected communities in remote areas and to promote behavior change.

Face-to-face risk education sessions were suspended in States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Eritrea, Senegal, and Yemen, as well as in states not party Armenia, Lebanon, Myanmar, Syria, and Vietnam. In some countries, community-based risk education was generally not impeded by COVID-19 restrictions, for example in Lao PDR and Somalia. In Palestine, UNMAS was able to continue to disseminate risk education messages widely through its “informal street sessions.”[91] In Cambodia and Nigeria, risk education sessions were conducted for much smaller groups. In Thailand, small group sessions continued to be provided in nine refugee camps. In South Sudan, only emergency risk education was permitted.

However, due to the creativity of mine action centers, service providers, and the broader mine action community, in many countries risk education programs were adapted to constraints and restrictions imposed due to COVID-19. In some countries, risk education operators integrated COVID-19 prevention messages into their usual activities.[92] In Iraq, the Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA) temporarily reassigned the risk education workforce to COVID-19 response efforts. In Senegal, Humanity & Inclusion (HI) reallocated unused mine action funding to COVID-19 prevention efforts. In Thailand, village health volunteers, tasked with disseminating COVID-19 messages, worked with the Thailand Mine Action Centre (TMAC) to provide mine risk education messages in affected areas.[93]

Risk education programs explored alternative means of disseminating messages electronically and remotely. In Vietnam, text and voice messages were used to pass on messages about risk education and COVID-19.[94] In Afghanistan, TV and radio and vehicles with loudspeakers were used to continue risk education programs.[95] The use of technology and social media was however not as effective in reaching affected communities in some remote areas of Cambodia and Lebanon, where use of social media is relatively low.

Victim assistance activities and services were strongly impacted by COVID-19 restrictions, including in Afghanistan, Armenia, BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, Georgia, Iraq, Libya, Myanmar, Senegal, Syria, Thailand, Uganda, Vietnam, and Yemen. In Yemen, the healthcare system was “on the brink of collapse” in 2019.[96] It “in effect collapsed" with the additional impact of COVID-19.[97] Operators reported that during the pandemic coordination was weak or non-existent in countries that had already experienced organization limitations, including Chad, Senegal, and Sierra Leone.

Mitigation strategies included assessments of mine victims' needs or the socio-economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic,[98] the provision of psychological support and follow-up rehabilitation services remotely, and the provision of hygiene kits and information on COVID-19 prevention measures to beneficiaries and technical personnel. In Colombia, only urgent services continued uninterrupted and follow-up services instead were provided by telephone. Coordination of victim assistance efforts was reportedly maintained in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Libya, and Myanmar.

Responses to Monitor questions on COVID-19 noted that survivors and other persons with disabilities were not able to access services and rights on an equal basis to others during the pandemic in a number of mine-affected countries, including in Cambodia,[99] Lao PDR, Senegal, Sierra Leone,[100] Syria, Tajikistan, and Yemen. This finding is consistent with a United Nations study that found persons with disabilities were at greater risk of discrimination in accessing healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic.[101]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Addressing the Impact

The Oslo Action Plan, agreed by States Parties in November 2019 at the Fourth Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty, highlights a number of best practices agreed by States Parties that contribute to the effective implementation of mine action programs. These include demonstrating high levels of national ownership; developing evidence-based, costed and time-bound national strategies and workplans; and keeping national mine action standards up to date in accordance with the latest International Mine Action Standards (IMAS).

Clearance coordination

In 2019, clearance programs in the majority of States Parties with remaining contamination were managed and coordinated through national mine action centers. Afghanistan, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ecuador, Iraq, Mauritania, Niger, Palestine, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, and Zimbabwe all had national bodies in place responsible for their national mine action programs.

Croatia, in a move to form an integrated and widely functioning civil protection system, dissolved the Croatian Mine Action Centre (CROMAC) as a legal entity and integrated it into the Ministry of the Interior as a Civil Protection Directorate on 1 January 2019.[102] The Civil Protection Directorate has taken on all roles previously undertaken by CROMAC.[103]

Cyprus has no national mine action center, as the remaining contamination is reported to be in areas under Turkish control. The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) coordinates mine action on behalf of the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP).[104]

Eritrea has provided few updates on its mine action program, although noted in its Article 5 extension request submitted in 2019 that it was in the process of restructuring the Eritrean Demining Authority.[105] It was stated that this restructuring had presented obstacles to Eritrea submitting its extension request and a workplan beyond its deadline of February 2020.[106]

Ethiopia moved responsibility for its mine action program from the Ethiopian Mine Action Office (EMAO) to the Head Office of the Ministry of Defense. This was reportedly to allow the Defense Minister to manage mine action activities and resources directly, to ensure an adequate level of authority for dealing with the remaining contaminated areas on Ethiopia’s borders, and to better communicate with donors.[107]

Nigeria has no mine action authority, but the UN Humanitarian Response Program includes a mine action sub-sector that takes responsibility for planning, coordination, the mapping and marking of hazardous areas, risk education and referral of survivors.[108] An Inter-Ministerial Committee was formed in 2019 and tasked with developing a national mine action strategy and a workplan for survey and clearance.[109]

Oman’s Article 7 transparency report for 2018 stated that it was working towards establishing a national mine action center.[110]

Ukraine’s mine action program is currently managed by the Ministry of Defense with support from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).[111] A Law on Mine Action in Ukraine, adopted in January 2019, which would enable the establishment of a mine action center, has not been implemented. An amendment to the law was submitted to parliament in February 2020.[112]

In Yemen, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is supporting the establishment of a Yemen Mine Action Coordination Centre (YMACC) in Aden. It is anticipated that the YMACC will ensure better coordination among mine action entities, and will take the lead on national standards, longer-term plans for survey and clearance, staffing and procurement, and national support plans.[113] The process has advanced significantly in the south of the country, but UNDP has little or no access in the north.[114]

National Mine Action Strategies

Mine Action Strategies and the development of workplans are crucial for strengthening national ownership of a mine action program and to enable greater transparency and accountability through monitoring and reporting. It can also help states align their mine action efforts with broader humanitarian and development efforts and boost their ability to leverage international funding.

Twenty States Parties had national mine action strategies in place in 2019, although Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Mauritania, Palestine, Somalia, Sri Lanka and Tajikistan all have strategies in place up to 2020 and need to update them. The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) has plans to support the update of strategies in Afghanistan and Somalia.[115] Afghanistan intends to develop the next strategic plan in 2020–2021 and has a 10-year workplan in place for April 2013–2023.[116]

Chad, the DRC, and Sudan had strategies that expired in 2019 and need updating. Sudan and the DRC have reported that the development of their strategies is in process.

States Parties Cyprus, Eritrea, Niger, Nigeria, Oman, Serbia, and Ukraine do not have mine action strategies in place. The GICHD plans to work with Ukraine to develop a mine action strategy, with a workshop due to be held in 2022.[117]

Iraq provided a strategic plan with its Article 5 deadline extension request in 2017, although this was outdated by the need to address the massive contamination resulting from the conflict with the Islamic State. The plan provides general priorities for implementation. In 2018, Iraq reported that it has formed a committee with the purpose of updating the plan so that it covers the period up to its Article 5 deadline of 2028.[118]

Serbia has a workplan to completion provided in its Article 5 extension request, which was submitted in 2018.[119]

Yemen’s original mine action strategy is now outdated and does not reflect the current situation in Yemen due to the ongoing conflict.[120] UNDP plans to assist Yemen to update its strategy when there is a lasting cessation to hostilities.[121]

Information management

States Parties not yet using the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) include BiH, Croatia, Eritrea, Niger, Oman, Serbia, and the United Kingdom (UK).

The first goal of BiH’s National Mine Action Strategy for 2018–2025 is to ensure sound information management standards, tools and processes.[122] Through 2019, the BiH Mine Action Centre (BHMAC) was using its own information management system, the BiH Mine Action Information System (BHMAIS).[123] UNDP is supporting a European Union (EU) funded project to improve information management through the development of a web-based database.[124]

Croatia has an information management system that is compliant with IMAS and allows disaggregation of contamination by type and land release method.

It is not clear what information management systems are used by Eritrea, Niger, and Oman.

The UK does not use IMSMA but has an information management system in place.

As of 15 October 2020, five States Parties with clearance obligations had not submitted Article 7 transparency reports for calendar year 2019: the DRC, Eritrea, Niger, Senegal, and Sri Lanka.[125] Eritrea has not submitted an Article 7 report since 2014.

National Mine Action Standards

In March 2019, the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan (MAPA) updated its national standards and introduced new standards for the clearance of improvised mines.[126]

In Iraq, the challenge of contamination by improvised mines and other improvised explosive devices (IEDs), particularly in urban areas such as Mosul, led to the development of new standards on IED disposal, published in February 2019.

During 2019, national standards were being reviewed in Angola, while Sudan’s national standards were awaiting endorsement as of May 2019. UNMAS reported constant review of national technical standards and guidelines for South Sudan.

Turkey reported elaborating its national standards in 2019 with support from UNDP and the GICHD. A land release national mine action standard is under development in Colombia. Somalia’s revision of national standards was due to be completed in 2019. In April 2019, Ukraine adopted Mine Action, Management Processes, and Basic Provisions to IMAS, which were adapted to the specific situation in Ukraine. They are now being tested.[127]

UNDP is planning to work with the GICHD to update and develop the Yemen National Standards, which are out of date and need to be revised.[128]

Chad reported that it will revise its standards on land release, supervision of organizations, and inspection of contaminated land in 2020.[129]

Risk education coordination

In 2019, 23 States Parties had national institutions in place for coordinating risk education. In most cases, risk education is coordinated by the mine action center, although for states with school-based programs, the Ministry of Education takes on a coordination role.

In Croatia, the Civil Protection Directorate was responsible for risk education. [130] UNMAS is responsible for risk education in Cyprus, Palestine, and in Gaza, and UNDP coordinates risk education in Ukraine.

States Parties that did not report risk education coordination included Oman and the UK. Eritrea provided no information.

In 2019, risk education coordination meetings were reported in 10 States Parties: Afghanistan, Cambodia, Colombia, the DRC, Iraq, Palestine, Senegal, South Sudan, Sudan, and Yemen. The main topics discussed at risk education coordination meetings are usually coordination, sharing information and innovation best practices, and developing or updating plans and strategies.

In Chad, Somalia, Thailand, Ukraine, and Zimbabwe, risk education may be discussed as part of broader mine action meetings.[131] In the DRC, Somalia, South Sudan, and Ukraine, it was reported that risk education is discussed during mine action sub-cluster meetings.[132]

No risk education working groups were reported for Angola, BiH, Croatia, Cyprus, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Niger, Peru, Serbia, Tajikistan, or Turkey.

In Afghanistan, it was reported that risk education technical working group meetings are led by the Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC). The meetings take place every two months and also on an ad hoc basis as required.[133]

In Colombia, coordination meetings for risk education are held three times a year, but there is currently no system for assigning municipalities to risk education operators. Operators must coordinate among themselves to avoid duplication.[134]

In the DRC, the National Risk Education Program of the Congolese Mine Action Center (Centre Congolais de Lutte Antimines, CCLAM) organizes meetings on a quarterly basis.[135]

In Iraq, coordination meetings for risk education are supposed to be held every month, but only one meeting was reported during 2019.[136] Risk education messages and materials are validated by the Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) and the Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA).[137]

Yemen has two risk education technical working groups, one based in the north of the country and another based in the south. Topics at group meetings include the signing of memoranda of understanding, aligning materials and messaging, coordination, tasking and advocacy.[138]

In Senegal, there is no regular coordination meeting, although the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reported meeting every two to three months with the Senegal National Mine Action Centre (CNMAS).[139] Similarly, in BiH, there is no risk education coordination mechanism, but the ICRC reported meeting regularly with the regional offices and upon need with the BHMAC.[140]

Risk education is reported to be included within the national mine action strategies of Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, the DRC, Somalia, and Tajikistan. In addition, Colombia, Ethiopia, and Turkey reported having national risk education workplans.

Not all States Parties have national standards to guide risk education operations at a national level, although operators implementing risk education reported working to IMAS and their own Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). Risk education national standards were reported to be in place in Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Colombia, the DRC, Iraq, Palestine, Senegal, South Sudan, Sudan, Thailand, and Zimbabwe. In Palestine, it was reported that there were risk education standards that were used in the West Bank, but not in Gaza.[141]

Thailand was updating its risk education standards in 2019. In Angola and Somalia, standards were under review and awaiting approval,[142] while in Cambodia they were under development.[143] Chad reported that it would review its risk education national standards at the end of 2020.[144]

In certain contexts, risk education, by necessity, needs to work across international borders to ensure that populations transiting mine-contaminated border areas are informed of the risks. On the Thailand-Myanmar border, Humanity & Inclusion (HI) is the sole risk education operator in the nine camps in Thailand for refugees from Myanmar, making it challenging to coordinate with risk education actors at a national level in either Thailand or Myanmar. In 2019, HI organized an information sharing workshop with risk education and mine action actors working along the border.[145]

Victim assistance coordination

Participation of victims and their representative organizations[146]

Victims were reported to be included through representation in coordination in Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand. States Parties rarely reported on the actual process to include input from victims in decision-making or on the outcomes of victim participation. Therefore, there is little direct evidence that the input from victims is considered or acted upon. In some states, victims’ representative organizations and other service providers involved in coordination and planning reported that the concerns and contributions of victims were not genuinely taken into account, despite their attendance at relevant meetings.

A specific IMAS on victim assistance was developed in 2018–2019, and in May 2020, it was approved by the IMAS Review Board with the rationale that the mine action sector, under the governance of national mine action authorities, “is well placed, through its direct links with [explosive ordnance] EO-affected communities, to gather information about victims and their needs, to provide information on relevant services and to refer them to the government body.” The ICBL engaged in the process to facilitate groups of survivors to define by themselves what they may contribute, given their specific expertise. Although contributions from survivor organizations were not included in the final document, in responding to the Monitor, they have raised the following points about their work:

- Assess the needs of network members, disaggregated by sex, age, and disability, in order to inform the development of victim assistance national action plans and other policies relevant to the sectors that victim assistance is part of;

- Contribute to the development of relevant national strategic plans in other sectors;

- Enable survivors and other persons with disabilities at the community level to facilitate efforts for their rehabilitation and socioeconomic inclusion;

- Conduct peer support and serve as a role model for other organizations and institutions;

- Link and refer to services;

- Support the participation of survivors during initial data collection to identify victims, including survival outcomes, types of injuries, age, gender, pre-existing impairments, civilian or military status, and specific needs;

- Develop partnerships and facilitate networking;

- Collaborate with relevant government sectors, including national mine action offices and actors;

- Represent victims at national and international meetings, conferences and other events relevant to victims;

- Share experiences and good practice with other organizations;

- Map and compile detailed profiles of service providers and disseminate to the relevant sectors;

- Facilitate mine risk education sessions while raising awareness of the rights of victims at the local community level; and

- Conduct rights advocacy at the national level.

In 2020, the Monitor began a rolling survivor survey, engaging active survivors to ask other survivors about what has happened in relation to victim assistance over the last five years, the current situation, and what needs to happen next. The questions are based on the victim assistance actions of the Mine Ban Treaty action plans and the ICBL-CMC strategic plan. A snowballing format is applied, whereby survivors engage other mine-affected members of the population for the survey.

A relevant government agency to coordinate victim assistance[147]

Of the States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, 21 reported victim assistance coordination linked to disability coordination mechanisms that considered issues related to the needs of mine/ERW victims. The States Parties with coordination mechanisms in 2019–2020 were: Afghanistan, Angola, Albania, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, the DRC, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Turkey. Angola’s coordination mechanism is not interconnected with disability rights coordination. While Croatia has designated several ministries, which include those responsible for disability rights, they do not have inter-ministerial coordination nor demonstrate awareness of victim assistance. Serbia’s victim assistance coordination had also stalled.

Multi-sectoral efforts in line with the CRPD[148]

Adopting, and implementing, a comprehensive inter-ministerial plan of action that identifies gaps and aims to fulfill the rights and needs of victims and, or among, other persons with disabilities, is a key step toward ensuring a coordinated response to the needs of mine victims in each State Party.

Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand, all have a current plan that addresses national victim assistance activities, while Zimbabwe has a set of measurable objectives.

Afghanistan, Algeria, Burundi, Cambodia, Croatia, Senegal, South Sudan, Uganda, and Yemen need to revise, finalize, or adopt a draft and implement their national disability plan, policy, or strategy that includes objectives responding to the needs of victims and recognizing its victim assistance obligations and commitments, together with a monitoring structure. Mozambique still has to implement the Action Plan for Assistance to Victims through relevant government departments and ministries.

States Parties that need to develop a plan or strategy include the DRC, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Nicaragua, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, and Turkey. In the meantime, the DRC requires a sustainable planning and coordination mechanism, working at both national and local levels, to increase efforts to implement the victim assistance objectives of its national mine action strategy. Turkey, which now has coordination, must develop a plan for implementation of victim assistance. Newer States Parties, Palestine and Sri Lanka, are yet to create a strategic framework for victim assistance.

National referral mechanisms[149]

States Parties can improve accessibility to services for mine victims by ensuring that existing data collection, needs assessments, and service providers have the capacity to make referrals to the appropriate health and rehabilitation facilities. Some victims may require referral to specialized services, referral from one health facility to another, or referrals for travel and treatment abroad. Referral mechanisms can involve national level mechanisms as well as local referral networks, including through community-based rehabilitation systems.

National governmental bodies providing referrals included a range of both mine action centers and government ministries, such as: Albania’s Mines and Munitions Coordination Office; Algeria’s Ministry of National Solidarity, Family and the Status of Women; Angola’s Ministry of Assistance and Social Reintegration; the Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority’s data department; Colombia’s Directorate for Comprehensive Mine Action (Descontamina Colombia) and the broader government-run reparations program at the Victims’ Unit; the Rehabilitation and Integration Division within Eritrea’s Ministry of Labor and Human Welfare; Iraq’s Directorate for Mine Action; and the Tajikistan Mine Action Center. In Thailand, although victim assistance is primarily implemented by the social security and health ministries, the Thailand Mine Action Center (TMAC) conducted follow-up trips to visit mine victims in clearance operation areas. Yemen reported referrals as part of an ongoing victim survey and referral mechanism.

Many more non-governmental organizations (NGOs) provided referrals at a national or local level in the States Parties with victims, including a range of survivor networks, national NGOs, disabled persons’ organizations (DPOs), and international NGOs—notably HI—as well as the ICRC and national Red Cross and Red Crescent movements.

However, in States Parties where survivors are not aware of their rights due to a lack of survivor assistance coordination, as reported in the DRC, existing measures benefiting mine/ERW survivors, such as free medical care and prostheses, may remain inaccessible.[150]

Centralized database with needs and challenges[151]

States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty commit to assess the needs of victims. This commitment includes assessing availability and gaps in services and support, and assessing existing or new activities that are required to meet the needs of victims in the frameworks of disability, health, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction. Assessment also provides an initial opportunity to refer victims to existing services.

The Oslo Action Plan calls for States Parties to use a centralized database that includes information on persons killed and injured, and the needs and challenges of mine survivors.[152] In 2013, new updates to the IMSMA NG (Next Generation) included a victim assistance module, which will facilitate the monitoring and tracking of victims’ access to their rights and the accountability of victim assistance processes.[153] However, some data management systems based on more modern technologies may not be centralized.

Survey activities and assessments were often ongoing. Afghanistan’s National Disability Database was under development and planned to be installed in 2020. These statistics on persons with disabilities and the families of those killed will be used to coordinate with the Ministry of Finance, Pension Department, and Population Registration Department to provide the necessary services. In Cambodia, village level quality of life assessments for victims and other persons with disabilities continued through 2019. Data collection on the needs of mine/ERW victims was ongoing in Colombia and new data management systems were put into use during the period.

Croatia’s development of a unified database on the needs of mine/ERW victims has stalled since 2017. Thailand reported that mine survivors are included in disability assessments. In Ukraine, the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) and Danish Demining Group (DDG) conducted a joint needs assessment of child mine/ERW survivors in 2019 in government-controlled areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, with support from the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF).[154] In Yemen, mine/ERW victims were registered with the national mine action center through ongoing survey. Somalia, Ukraine, and Yemen needed to significantly improve the collection of data and create a usable database of victims’ needs. Iraq needed to establish a unified and coordinated system of data collection and analysis for survivors and other persons with disabilities.

According to Action #35 of the Oslo Action Plan, data should be disaggregated by gender, age and disability, and this information should be made available to relevant stakeholders to ensure a comprehensive response.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Oslo Action Plan highlights the importance of gender and ensuring that the different needs and perspectives of women, girls, men, and boys are considered and inform all areas of Mine Ban Treaty implementation and national mine action programs, in order to deliver an inclusive approach. States Parties are encouraged to remove barriers to full, equal and gender-balanced participation in mine action and treaty meetings. The Oslo Action Plan has some 37 references to gender.[155] Moreover, after significant input on the theme, each committee of the Mine Ban Treaty, including those for Article 5 and Victim Assistance, adopted a gender focal point.[156]

The previous five-year plan of the Mine Ban Treaty, the Maputo Action Plan adopted in 2014, had just seven references about gender. However, under that previous plan States Parties did already commit to implementation in an inclusive and gender-sensitive manner.

The increased focus on gender in mine action coincides with the 20-year anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS), which was adopted unanimously in October 2000. Resolution 1325 emphasizes a gender-based approach to mine action among its provisions, specifying “the need for all parties to ensure that mine clearance and mine awareness programmes take into account the special needs of women and girls.” Resolution 1325 provided a basis for future developments.[157]

In 2019, the third revision of the UN’s Gender Guidelines for Mine Action Programmes was produced.[158] The guidelines were first released in February 2005, with a second revision in 2010. In March 2019, the Gender and Mine Action Programme (GMAP) integrated into the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), gaining a stronger institutional placement although no longer having an advocacy role as it did previously. That role was taken up by ICBL members and other civil society organizations and is reflected in the Oslo Review Conference Working Group on Gender, which was established in the lead up to the Fourth Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty.

Intersectionality became a strong contextual focus of gender considerations in mine action as the Oslo Action Plan period commenced.[159] This was concurrent with a broader trend in international law and policy. For example, UN Women also highlighted the need for this approach: “Injustices must not go unnamed or unchallenged now different communities are battling various, interconnected issues, all at once. Standing in solidarity with one another, questioning power structures, and speaking out against the root causes of inequalities are critical actions for building a future that leaves no one behind.”[160]

States Parties Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, the DRC, Iraq, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Zimbabwe have all included gender as a component of their national mine action strategies. GMAP has supported several States Parties to integrate gender into their strategies and workplans.

In Afghanistan, gender and diversity mainstreaming is one of the goals of their national mine action strategy, and the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan has a gender and diversity strategy.[161] Within the framework of this strategy, proposals to conduct mine action activities are evaluated based on their technical approach, budget and consideration of gender.

The BiH Mine Action Strategy for 2018–2025 sets five key strategic goals, including gender-sensitive awareness raising.[162]

Cambodia is implementing a Gender Mainstreaming in Mine Action Plan for 2018–2022, which includes the development of gender mainstreaming guidelines.[163] Cambodia also reports promotion of the equal participation of women in mine action processes, services for survivors, risk education, and advocacy activities by updating report formats through inclusion of age, sex, and disability.

In Chad, government policy exists to ensure the integration of gender-based considerations at all levels of mine action. In 2020, the National High Commission for Demining (HCND) reported that its staff included women, while it is noted that the Deputy Coordinator of the HCND is a woman.[164]

Croatia also has national legislation on gender, which is mainstreamed through the mine action sector, and in particular in its risk education activities.[165]

Colombia continued to receive technical support from the GICHD for the development of Gender Guidelines for Comprehensive Action Against Antipersonnel Mines (Acción Integral Contra Minas Antipersonal, AICMA).[166]

In the DRC, the Congolese Mine Action Center (CCLAM) reported that its gender unit sits within the advocacy department and aims to ensure the mobilization and inclusion of women in mine action.[167] The Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) in Iraq has also had a Gender Unit in place since 2017.[168]

Many states now have greater numbers of women working in the sector, including in mine clearance teams. Mixed or all-women clearance teams have been reported in Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Colombia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Senegal, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Vietnam, Zimbabwe, as well as other area Nagorno-Karabakh.

Serbia reported that there is equal access to employment in the fields of survey and clearance for qualified women and men.[169] Sudan reported that women are included in all aspects of mine action, from key departments at the national mine action center, to field operations.[170] In Ukraine, around 20% of deminers are women,[171] while Zimbabwe reported that 30% of the staff at its national mine action center are women.[172]

In both Thailand and Turkey, military regulations are reported to prevent women from working in demining teams.[173] In 2019, the Thailand Mine Action Centre (TMAC) reported that 40% of its staff were women, although they were mainly in administrative positions. The Turkish Mine Action Center (TURMAC) reported that 45% of its staff were women.[174]

While men and boys represent the majority of reported mine casualties, women and girls are likely to be disproportionally disadvantaged as a result of mine/ERW incidents. They often suffer multiple forms of discrimination as survivors. Gender is a key consideration in victim assistance programming, but reporting was often limited to statistical disaggregation of casualties and service beneficiaries.

In Cambodia in 2019, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, with the support of the Australia-Cambodia Cooperation for Equitable Sustainable Services (ACCESS) Program, conducted the first consultative workshop involving women with disabilities under the National Action Plan to Prevent Violence Against Women.[175]

Guidance on Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Abuse was published by GMAP in 2019. The publication consultation process, with partners both in Geneva and in mine-affected countries, was conducted by the GICHD in collaboration with the Monitor’s victim assistance gender focal point from the ICBL-CMC, with financial support and leadership from Canada.[176]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Mine Clearance in 2019

The Mine Ban Treaty obligates each State Party to undertake to destroy or ensure the destruction of all anti-personnel mines in mined areas under its jurisdiction or control, as soon as possible but not later than 10 years after the entry into force of the treaty for that State Party.

Among States Parties, total clearance of landmines in 2019 was at least 156km².[177] This represents an increase from the estimated 146km² cleared in 2018. At least 123,375 landmines were cleared and destroyed in 2019.

Antipersonnel mine clearance in 2018–2019[178]

|

State Party |

2018 |

2019 |

||

|

Clearance (km²) |

APM destroyed |

Clearance (km²) |

APM destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

30.04 |

8,947 |

28.01 |

7,801 |

|

Angola |

1.04 |

1,707 |

1.92 |

1,943 |

|

Argentina* |

See clearance figures under UK |

|||

|

BiH |

0.92 |

2,101 |

0.53 |

963 |

|

Cambodia |

36.66 |

10,031 |

20.93 |

15,425 |

|

Chad |

N/R |

N/R |

0.29 |

998 |

|

Chile |

0.65 |

4,000 |

0.55

|

4,093 |

|

Colombia |

0.84 |

322 |

1.39 |

311 |

|

Croatia |

48.82 |

1,095 |

39.16 |

2,530 |

|

Cyprus** |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

DRC |

0.28 |

5 |

0.21 |

26 |

|

Ecuador |

0.014 |

247 |

0.002 |

62 |

|

Eritrea |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Ethiopia |

1.40 |

582 |

1.75 |

128 |

|

Iraq |

4.03 |

7,944 |

46.56 |

12,378 |

|

Niger |

N/R |

N/R |

0.01 |

323 |

|

Oman |

0 |

0 |

0.13 |

0 |

|

Palestine |

0.026 |

626 |

0.01 |

106 |

|

Peru |

0.015 |

140 |

0.08 |

1,113 |

|

Senegal |

0 |

25 |

0 |

0 |

|

Serbia |

0.21 |

29 |

0.60 |

22 |

|

Somalia |

N/R |

52 |

0.12 |

6 |

|

South Sudan |

8.53 |

1,166 |

1 |

405 |

|

Sri Lanka |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

|

Sudan |

0.97 |

31 |

0.87 |

1 |

|

Tajikistan |

0.59 |

4,998 |

0.53 |

5,219 |

|

Thailand |

0.52 |

7,405 |

0.09 |

2,677 |

|

Turkey |

2.08 |

22,220 |

0.67 |

25,959 |

|

Ukraine |

N/R |

N/R |

1.70 |

N/R |

|

UK* |

6.44 |

619 |

3.61 |

319 |

|

Yemen |

0.64 |

1,691 |

3.10 |

1,536 |

|

Zimbabwe |

2.11 |

22,013 |

2.75 |

39,031 |

|

TOTAL |

146.82 |

97,996 |

156.57 |

123,375 |

Note: N/R=not reported; APM=antipersonnel mines.

* Argentina and the UK both claim sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas, which still contain mined areas.

** Cyprus states that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under Cypriot control.

Based on the reported data, Iraq has cleared the most land in 2019 at 46.56km². Of this, 40.24km² was clearance of improvised mines in Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) managed areas and 3.17km² in areas managed by the Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA).[179] In the past, reporting of clearance of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) has not been consistently included in clearance figures, but in its Article 7 transparency report for 2019, Iraq recorded all abandoned IED areas as antipersonnel mine contamination until cleared.

Afghanistan cleared 28.01km² despite ongoing conflict in some areas. This is a reduction from the 30.04km² cleared in 2018. The Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) reported to the Monitor that it had only been able to secure about 50% of the funding required, and thus could only achieve half of the planned clearance.[180]

Yemen was able to clear 3.1 km² and destroy 1,536 antipersonnel mines in 2019, despite the ongoing conflict and insecurity. A total of 66,701 explosive remnants of war (ERW) were cleared and destroyed in 2019.[181] Clearance operations in Yemen are focused on high-threat and high-impact spot tasks with the aim to allocate resources where they will have a more significant impact for local communities.[182]

Zimbabwe cleared and destroyed the largest number of landmines in 2019, reporting 39,031 devices cleared from 2.75km².

Chile announced the completion of its clearance obligations in March 2020, with the last mines removed on 27 February 2020. Chile reports having cleared 159 areas over the last 18 years, clearing and destroying a total of 177,725 mines.[183] During 2019, Chile reported the release of 1.74km² of land (0.55km² through clearance), and the clearance of 4,093 antipersonnel mines and 1,187 antivehicle mines. In the first two months of 2020, Chile released a further 2.69 km² of land, including 0.60km² which was cleared. A total of 12,526 antipersonnel mines and 10,170 antivehicle mines were reportedly cleared during this two-month period.[184]

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ecuador, Niger, Oman, Palestine, Peru, Serbia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand and Turkey all cleared under 1km² in 2019. However, despite clearing only 0.67km², Turkey cleared and destroyed 25,959 landmines.

Three States Parties reported no clearance in 2019. Senegal has not reported any clearance since 2017. Cyprus states that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under its control.[185] Argentina reports that it is mine-affected as a result of its claim to sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas, but that it is unable to meet its Article 5 obligations because it has not had access to the islands due to the “illegal occupation” by the United Kingdom (UK).[186]

Niger reported clearance of 0.01km² in 2019 and the destruction of 323 antipersonnel mines. This is the first time that Niger has reported clearance since 2017.[187]