Cluster Munition Monitor 2021

The Impact

Jump to a specific section of the chapter:

Assessing the Impact: Contamination | Casualties

Addressing the Impact: Clearance | Risk Education | Victim assistance

This summary reports on the impact of cluster munitions globally and the efforts and challenges to address the impact in the States Parties with responsibility for clearance of cluster munition remnants and to cluster munition victims. The period covering 2020 into 2021 proved to be a challenging time for the implementation by States Parties of their obligations under the Convention on Cluster Munitions. In many countries, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in restrictions that hampered clearance and risk education operations and created additional challenges for victims to access services and support. The first part of the convention’s Second Review Conference was held virtually in November 2020, while the second part was postponed until 2021. As a result, the Lausanne Action Plan—the new set of five-year strategic commitments to further states’ efforts to address the impact of cluster munitions—has not yet been formally adopted at the time of writing this report. In effect, 2021 saw a prolonged transition period between the Dubrovnik and Lausanne action plans, while States Parties endeavored to make progress in much altered national and international environments.

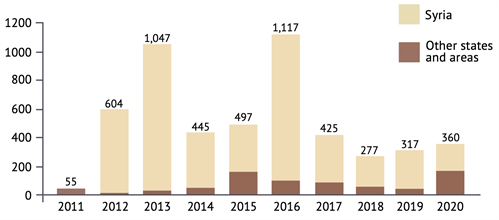

A total of 360 cluster munition casualties in eight countries and one other area were recorded in 2020, marking a continued increase from the annual casualty totals for 2019 and 2018. Of the casualties in 2020, 142 were from new attacks in Azerbaijan and ongoing attacks in Syria, while 218 were caused by cluster munition remnants. As has been the case each year since 2012, Syria had the highest annual casualties of any country. As of the end of 2020, the total number of cluster munition casualties for all time, recorded by the Monitor, reached 22,930 including casualties from both cluster munition attacks and from unexploded submunitions. Estimates calculated from various sources range from 56,500 to 86,500 casualties for all time, globally.

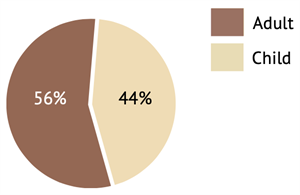

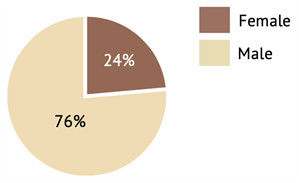

Cluster munitions continue to significantly impact children. Children accounted for 44% of all casualties from attacks and cluster munition remnants during 2020, where the age was recorded. In 2020, more than three quarters of casualties (76%) were men and boys where the sex was recorded. Although the age and sex of cluster munition casualties are not adequately disaggregated in historical data, men have consistently accounted for a majority of all casualties over time. Before the adoption of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in 2008, men and boys accounted for the vast majority of casualties (84%) where the sex of casualties was recorded.

Some positive progress in the clearance of cluster munition remnants was made in 2020. Two States Parties, Croatia and Montenegro, fulfilled their obligations under Article 4 to complete clearance; while the United Kingdom (UK), which completed mine clearance in the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas, also confirmed that no cluster munitions remained to be cleared. States Parties reported clearing more than 63km² of land in 2020, and at least 80,925 cluster munition remnants.[1] While this represents a drop in clearance output since 2019, it still represents steady progress given the unique and unchartered challenges created by the pandemic.

However, there was also less welcome news. In four States Parties—Afghanistan, Chile, Mauritania, and Somalia—no clearance took place in 2020. Afghanistan, initially optimistic about meeting its March 2022 deadline, became the third State Party to submit an extension request in 2021, after Chile and Mauritania.[2] New cluster munition contamination occurred in Azerbaijan and the area of Nagorno-Karabakh as a result of the use of cluster munitions in multiple locations in October 2020, including in populated urban areas.[3] Cluster munition remnants contamination was also noted in Armenia after the 2020 conflict.[4] Ten States Parties remain contaminated with cluster munition while two signatories, 14 non-signatories, and three other areas have, or are believed to have, land containing cluster munition remnants.

Risk education remained a crucial intervention in 2020, given the number of people continuing to live in contaminated areas. Some States Parties demonstrated efforts to target specific groups vulnerable to the threat of cluster munition remnants contamination, such as children through school programs or hard-to-reach nomadic groups known to traverse contaminated areas with animal herds. Efforts were also made in some countries to better reach persons with disabilities through adapted materials and approaches, including the use of sign language or subtitles, and disability inclusive training for community focal points. In 2020, emergency risk education was conducted in non-signatories Libya, Syria, and Yemen, as well as in the other area Nagorno-Karabakh. The COVID-19 pandemic restricted efforts to reach affected communities via interpersonal risk education methods, but operators responded by moving messaging online—on social media and mobile applications—or through more traditional methods such as broadcasting on TV and radio.

Victim assistance efforts under Article 5 continued in the face of increasing challenges. In most States Parties, progress was reported despite numerous barriers to services, including ongoing funding constraints and the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, significant gaps remained in increasing the availability, accessibility, and sustainability of healthcare and rehabilitation services via national ownership, and through integration with efforts under the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Some progress was reported in the provision of economic inclusion and financial assistance to victims; although this was an area where few sustainable measures were noted. As in past years, psychological support—particularly psychosocial support through peer-to-peer approaches—was severely lacking considering the level of need for such services.

Cluster munition remnants contamination

Global contamination

A total of 26 states and three other areas were known or suspected to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants, as of 1 August 2021. Ten of these are States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and have Article 4 clearance obligations, while two are signatories. Fourteen non-signatories and three other areas are also affected by cluster munitions.

Estimated cluster munition remnants contamination in states and other areas

|

More than 1,000km2 |

100–1,000km2 |

10–99km2 |

Less than 10km2 |

Residual contamination/ Unknown |

|

Lao PDR Vietnam |

Cambodia Iraq

|

Afghanistan Azerbaijan Chile Kosovo Libya Mauritania Nagorno-Karabakh Syria Ukraine Yemen

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina Chad Georgia Germany Iran Lebanon Serbia Somalia South Sudan Sudan Tajikistan Western Sahara |

Angola Armenia Dem. Rep. Congo

|

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold; signatories are underlined; and other areas are in italics.

Cluster munition remnants contamination in States Parties

States Parties that have completed clearance

Under Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties are obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under their jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention.

A total of 10 States Parties have reported completing clearance of cluster munition remnants. In 2020, States Parties Croatia and Montenegro declared that clearance of all cluster munition remnants on their territories was complete. States Parties the Republic of the Congo (2012), Grenada (2012), Norway (2013), and Mozambique (2016) have also each declared completion of clearance. States Parties Albania, Guinea-Bissau, Palau, and Zambia all completed clearance before the entry into force of the convention in 2010.[5]

Mauritania, which had reported fulfilment of its clearance obligations in September 2013, has since reported finding new cluster munition remnants contamination.[6]

Extent of contamination in States Parties

Massive cluster munition remnants contamination (more than 1,000km²) exists in one State Party, Lao PDR, while large contamination (between 100–1,000km²) exists in one State Party, Iraq. Three States Parties—Afghanistan, Chile, and Mauritania—are believed to have medium contamination (between 10–99km²). Afghanistan previously had below 10km², but in 2021 recorded new contamination. Five States Parties—Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Germany, Lebanon, and Somalia—have less than 10km² of contamination.

Lao PDR is the State Party most heavily contaminated by cluster munition remnants. Though the full extent of contamination is not known, 15 of Lao PDR’s 18 provinces are contaminated, with nine heavily contaminated.[7] Survey is ongoing in six provinces, with limited survey in three others. As of the end of December 2020, the total extent of confirmed hazardous area (CHA) in surveyed areas totaled 1,298.34km².[8] By June 2021, 1,371km² of CHA had been identified.[9] Clearance operators have reported the presence of at least 186 types of munitions in Lao PDR.[10]

The Regional Mine Action Center (RMAC) South in Iraq reported to the Monitor that as of the end of 2020, cluster munition remnants covered a total area of 162.81km² in the north, center, and south of the country.[11] The majority of contaminated areas are found in southern Iraq (147.65km²), but cluster munition remnants are also found in the Middle Euphrates region (10.99km²) and in the north, including in the Kurdistan region of Iraq (4.17km²).[12] In 2020, survey discovered 220 contaminated areas in Basrah and Muthanna, in southern Iraq, covering 17.14km².[13]

In its revised Article 4 deadline extension request of 29 June 2020, Chile stated that the estimate of contamination in the country was 64.61km², across four sites, according to a non-technical survey completed in 2019.[14] However, it is expected that this estimate will be further reduced by technical survey.

In 2019, Mauritania discovered previously unknown contaminated areas, dating from 1980 and 1990.[15] After an initial assessment of the contamination in February 2021, 14.02km² was found to be contaminated with cluster munition remnants. These areas are all located in the region of Tiris Zemmour in the north of Mauritania, bordering Western Sahara.[16] Further survey will be needed to determine the exact size of the contaminated areas.[17]

As of the end of 2020, Afghanistan reported 10 cluster munition contaminated areas, totaling 7.54km², located in Faryab, Nangarhar, and Paktya provinces.[18] However, in the first quarter of 2021, a further 11 areas were identified as contaminated in the provinces of Bamyan, Paktya, and Samangan, bringing the total remaining contamination to more than 13km².[19] Further contamination, around 3km², was also suspected in Paktya province, but survey had not been conducted due to the area being under the control of a non-state armed group (NSAG).[20]

Germany has found evidence of ShOAB-0.5 submunitions on or just below the natural ground surface (not exceeding some 30cm) over an area not exceeding 11km².[21] It has reported clearing 3.5km² of contaminated area between 2017 and 2020, leaving 7.5km² still to clear.[22]

The Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) told the Monitor that as of the end of 2020, cluster munition remnants contamination covered 7.29km² in three areas: Bekaa, Mount Lebanon, and southern Lebanon.[23] This included 0.92km² of new contamination discovered in 2020 in the northeast.[24]

Cluster munition remnants contamination in BiH primarily results from the 1992–1995 conflict related to the break-up of the former Yugoslavia.[25] BiH reported that as of the end of 2020, 2.05km² of contamination remained, estimated to contain some 2,300 KB-1 unexploded cluster submunitions.[26]

Chad’s remaining cluster munition contamination is small. The National High Commission for Demining (Haut Commissariat National de Déminage, HCND) reported to the Monitor in June 2021 that the last area known to be contaminated—742,657m² in Delbo village, West Ennedi province—had been cleared and was awaiting quality assurance to complete the land release process.[27] However, Mines Advisory Group (MAG) previously indicated that most of Tibesti province had yet to be surveyed, and noted the possibility that cluster munition remnants could be found around former Libyan military bases.[28]

The extent of contamination in Somalia is unknown but thought to be small. Cluster munition remnants are thought to remain along border areas with Kenya, in the north of Jubaland state, but no survey of contaminated areas has been possible primarily due to a lack of funding.[29]

Unconfirmed contamination in States Parties

State Party Colombia may have a small amount of residual contamination, although no known evidence has been found.[30] A World War II-type “cluster adapter” of United States (US) origin was used during an attack at Santo Domingo in 1998.[31] The Inter-American Court of Human Rights found the Colombian Air Force used an AN-M1A2 bomb, which it said meets the definition of a cluster munition.[32]

The UK completed clearance of mines in the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas in 2020 and confirmed there are no remaining areas where cluster munition remnants are suspected there. But it is estimated that more than 2,000 crates of AN-M1A1 and/or AN-M4A1 “cluster adapter” type bombs are remaining in UK waters in the cargo of a sunken World War II ship off the east coast of England.[33]

Cluster munition remnants contamination in signatories

Two signatories to the Convention on Cluster Munitions— Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—remain listed as having cluster munition remnants contamination. Signatory Uganda completed clearance in 2008.[34]

Angola has no confirmed contamination, but there may remain abandoned cluster munitions or unexploded submunitions. Some cluster munition remnants have been found and destroyed through explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) call-outs.[35]

DRC is suspected to have some small remaining areas of cluster munition contamination. The Congolese Mine Action Center (Centre Congolais de Lutte Antimines, CCLAM) reported to the Monitor in August 2020 that cluster munition remnants are thought to be present in five provinces—Ituri, Maniema, South-Kivu, Tanganyika, and Tshuapa—but that survey would need to be conducted to confirm the extent of contamination.[36]

Cluster munition remnants contamination in non-signatories and other areas

Fourteen non-signatories and three other areas have, or are believed to have, land containing cluster munition remnants on their territories.[37] The only non-signatory to have completed clearance of cluster munition remnants is Thailand, in 2011.

The full extent of contamination in many of the non-signatories and other areas is not known. However, Vietnam is believed to have massive cluster munition remnants contamination (more than 1,000km²), while Cambodia has large contamination (between 100–1,000km²). Five non-signatories and two other areas are each believed to have between 10–99km² of contamination, while six non-signatories and one other area are each thought to have less than 10km². The extent of contamination in Armenia is not known.

Vietnam is massively contaminated by cluster munition remnants, but no accurate estimate of the extent exists. In 2020, the Vietnam Mine Action Centre (VNMAC) reported to the Monitor that areas contaminated with explosive remnants of war (ERW) of all types comprised more than 5.7 million hectares (57,000km²). This represents more than 17% of Vietnam’s total land area, but contamination is concentrated mainly in the central provinces of Quang Tri, Quang Binh, Ha Tinh, Nghe An, and Quang Ngai.[38]

Cambodia has raised its estimate of cluster munition contamination in recent years due to the implementation of survey. The Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA) reported 658km² of contamination as of the end of December 2020.[39] Most of this contamination is concentrated in the northeastern provinces, along the borders with Lao PDR and Vietnam.[40]

Non-signatories thought to have between 10–99km² of contamination are Azerbaijan, Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen, and the other areas Kosovo and Nagorno-Karabakh.

The extent of contamination in both Azerbaijan and the area of Nagorno-Karabakh is unknown. Use of cluster munitions in October 2020 resulted in new contamination in both Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh.[41] Before the conflict in 2020, the HALO Trust had reported 70.48km² of cluster munition remnants contamination in Nagorno-Karabakh.[42] In Armenia, new contamination from the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh was identified in the Syunik region bordering Azerbaijan in 2021.[43] But the extent of cluster munition contamination is not known.

Contamination in Libya is a consequence of armed conflict in 2011 and renewed conflict since 2014, particularly in urban areas. In 2019, there were several instances or allegations of cluster munition use in Libya by forces affiliated with the Libyan National Army (LNA), including in an attack on Zuwarah airport in August 2019 where RBK-500 cluster munition remnants were found, and during attacks in and around Tripoli in May and December 2019.[44]

Cluster munitions have been used extensively in Syria in 13 of the country’s 14 governorates since 2012. From late April until June 2019, Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported attacks against opposition-controlled areas of Aleppo, Hama, and Idleb governorates on a daily basis.[45] Prior to that, cluster munition use and cluster munition remnants contamination were reported in the governorates of Aleppo, Dar’a, Deir-ez-Zor, Hama, Homs, Idleb, and Quneitra, as well as in the Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta.[46] Reported cluster munition attacks in Syria have decreased since mid-2017,[47] but they were still in use throughout 2019 and into 2020.[48]

Ukraine has reported that unexploded submunitions contaminate the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, in the east of the country.[49] The extent of contamination is not yet known.

In 2014, Yemen identified approximately 18km² of suspected cluster munition hazards, but the escalation of armed conflict since March 2015 has increased the extent of contamination in northwestern and central Yemen.[50] The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) confirmed that cluster munitions and other ERW contamination is widespread in the north, resulting from the air campaign and ground fighting.[51] In the south, with the exception of a few areas where the frontlines have shifted, there is no cluster munition remnants contamination.[52]

In Kosovo, as of January 2021, the Kosovo Mine Action Centre (KMAC) reported 11.4km² of cluster munition remnants contamination in 45 affected areas.[53]

Non-signatories Georgia, Iran, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, and the area of Western Sahara each have less than 10km² of known cluster munition remnants contamination.

Georgia is thought to be free of contamination, with South Ossetia being a possible exception.

The extent of contamination in Iran and Sudan is not known but is believed to be small.

Serbia reported a total of 2.09km² of contamination as of the end of 2020, made up of 0.71km² of CHA and 1.38km² of suspected hazardous area (SHA).[54]

South Sudan reported 5.78km² of contamination, but noted that analysis of previous clearance suggests that the projection underestimates the size of the problem.[55]

Tajikistan reported 0.79km² of cluster munition contaminated land, classified as CHA.[56]

Western Sahara reported 2.09km² of cluster munition contamination as of December 2020.[57]

Global cluster munition casualties

The Monitor gathers available data on cluster munition casualties recorded annually in individual countries and compiles statistics for each full calendar year. The Monitor also collects data on past casualties and records casualties over time for country profiles, and to revise aggregated global historical data on cluster munition casualties as new information becomes available.

As of the end of 2020, the total number of cluster munition casualties recorded by the Monitor globally for all time reached 22,930. The total includes casualties resulting directly from cluster munition attacks (4,656 casualties) in addition to casualties from unexploded remnants (18,274 casualties). Data begins in the mid-1960s amid extensive cluster munition attacks by the US in Southeast Asia, and continues to the end of 2020. The three countries with the highest recorded numbers of cluster munition casualties are Lao PDR (7,763), Syria (4,281), and Iraq(3,101).

As many casualties have gone unrecorded, a better representation of total casualties globally is roughly 56,500; a figure that has been calculated from various country estimates. Some higher end estimates put the total number of casualties for all time at between 86,500 and 100,000. However, these are based on extrapolations from limited data samples, which may not be representative of national averages or the actual number of casualties.[58]

Casualties directly caused by cluster munition attacks before the convention entered into force have been grossly under-reported. For example, no data or estimate is available for the most heavily bombed country, Lao PDR. Many thousands of cluster munition casualties from past conflicts have gone unrecorded, particularly casualties that occurred during extensive use in Southeast Asia, Afghanistan, and the Middle East (notably in Iraq, where there have been estimates of between 5,500 and 8,000 casualties from cluster munitions since 1991).[59]

However, since the entry into force of the convention in 2010, recording of the impact of cluster munition attacks has improved significantly. Concerningly, due to new use, casualties recorded from attacks have outnumbered those due to cluster munition remnants during this period.

Prior to the adoption of the convention in 2008, data on casualties from cluster munition attacks was severely lacking, including those among military personnel and other direct conflict actors, such as NSAG combatants and militias. Even with improved reporting, the disproportionately high ratio of civilian casualties identified during the Oslo Process to establish the convention has remained apparent.

Before 2008, a total of 13,306 recorded cluster munition casualties had been identified globally.[60] Since then, the number of recorded casualties has increased due to updated casualty surveys identifying pre-convention casualties, new casualties that have resulted from historical cluster munition remnants, as well as new use of cluster munitions during attacks and the remnants they have left behind.

Cluster munition casualties have been identified as having occurred in 14 States Parties, four signatory states, 17 non-signatories, and three other areas as of the end of 2020.

States and other areas with cluster munition casualties (as of 31 December 2020)[61]

|

More than 1,000 casualties |

100–1,000 casualties |

10–99 casualties |

Less than 10 casualties/unknown |

|

Iraq Lao PDR Syria Vietnam |

Afghanistan Angola Azerbaijan* BiH Cambodia Croatia Dem. Rep. Congo Eritrea Ethiopia Kosovo Kuwait Lebanon Russia Serbia South Sudan Western Sahara Yemen |

Albania Colombia Georgia Israel Nagorno-Karabakh Sierra Leone Sudan Tajikistan Uganda Ukraine |

Chad Guinea-Bissau Liberia Libya Montenegro Mozambique Somalia

|

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold; signatories are underlined; and other areas are in italics.

*Azerbaijan is included as having casualties for the first time due to cluster munition attacks in 2020.

The first cluster munition casualty in Mauritania was reported in 2021.[62] Although no casualties were identified in Mauritania before 2021, it is possible that cluster munition incidents occurred in the past that were not disaggregated from casualties caused by mines and other ERW.

Among the 14 States Parties that had cluster munition casualties recorded up to the end of 2020, 12 have a recognized responsibility for victims under the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[63] At least two States Parties—Colombia[64] and Mozambique[65]—have had cluster munition casualties reported, but do not believe that they have cluster munition victims or therefore have not recognized the responsibility to assist cluster munition victims. Both are also States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty, and have recognized their responsibility to assist landmine survivors.

The majority of all recorded cluster munition casualties for all time (57%, or 13,018) occurred in States Parties. As noted above, casualties directly caused by attacks in States Parties before the convention have been grossly under-reported.

A total of 604 casualties have been recorded in signatory states Angola, the DRC, Liberia, and Uganda.[66]

In non-signatory states, 8,897 cluster munition casualties have been recorded for all time.Since 2010, casualties from cluster munition attacks have only occurred in non-signatory states, with these casualties recorded in Azerbaijan, Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen. Of the 4,656 recorded casualties which occurred during cluster munition attacks, for all countries and areas for all time, just under half (45%, or 2,137) were reported in Syria since 2012.

In other areas where cluster munition casualties have occurred—Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara—a total of 411 casualties were recorded for all time to the end of 2020.

Cluster munition casualties in 2020

The Monitor recorded a total of 360 cluster munition casualties in 2020. These casualties occurred in eight countries and one other area, including three States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and five non-signatories.[67]

Cluster munition casualties in 2020

|

Cluster munition attacks casualties |

|

|

Azerbaijan |

107 |

|

Syria |

35 |

|

Cluster munition remnants casualties |

|

|

Syria |

147 |

|

Iraq |

31 |

|

South Sudan |

16 |

|

Yemen |

11 |

|

Lao PDR |

8 |

|

Afghanistan |

3 |

|

Cambodia |

1 |

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

1 |

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold andother areas in italics.

The total figure for annual casualties in 2020 includes those incurred at the time of attack (142) and people killed and injured in incidents from explosive cluster munition remnants (218).

The real number of new casualties each year, including 2020, is likely to be far higher. Due to a lack of consistency in the availability and disaggregation of annual casualty data, fluctuations and comparisons with previous annual reporting are not necessarily indicative of definitive trends.

Data on casualties is adjusted over time as new information becomes available. For example, data on cluster munition remnants casualties for past years in Syria, collected by the HALO Trust, was newly available in 2020. This significantly increased annual casualty totals and the casualty total for all time for Syria by more than 500 casualties since 2015. The new data confirmed that casualties in the country had previously been severely under-reported.

The 2020 cluster munition casualty total of 360 marks a continued increase from the updated annual totals, of 317 casualties for 2019 and 277 casualties for 2018.[68] However, 2018 was the year with the lowest annual global casualty figure recorded since the Monitor started recording cluster munition casualties from new use in Syria in 2012.

In 2020, as in past years, Syria had the most recorded annual cluster munition casualties of any country, with 182 casualties, representing just over half (52%) of all casualties recorded for the year. Despite a huge decrease proportionally, with Syria having recorded 83% of total cluster munition casualties in 2019, this continued the trend for each year since 2012 whereby Syria had the most annual casualties.[69] Since 2012, 80% of all cluster munition casualties globally were recorded in Syria.

Cluster munition casualties in Syria and all other states and areas 2011–2020

Note: Numbers above each bar indicate the total number of annual casualties.

Casualties from cluster munition attacks

More rapidly available reporting of casualties that have occurred during cluster munition attacks has been a significant outcome of increased international focus on the convention’s promise of ending casualties and suffering caused by cluster munitions.

A total of 142 casualties from cluster munition airstrikes in Syria (35) and shelling in Azerbaijan (107) were recorded in 2020, with 44 people killed and 98 injured. There may also have been casualties from attacks in Nagorno-Karabakh, but none were specifically documented.[70]

In 2020, several cluster munition attacks on schools and near hospitals were reported to have caused casualties.

On 1 January and 25 February 2020, schools in Syria’s Idleb governorate were hit by cluster munition shelling, resulting in civilian casualties including schoolchildren and teachers. The attack in January killed at least 12 civilians, including five schoolchildren, and injured at least 13 people at Abdo Salama School in the town of Sarmin, Idleb governorate.[71] In the attack in February 2020, Thawra school (also known as Al Baraem school) in Idleb was struck by cluster munition shelling, resulting in the death of three teachers and injuries to five other people.[72]

On 28 October 2020, a cluster munition attack on Barda, Azerbaijan, that killed 21 people and left another 60 injured, struck a residential neighborhood close to a hospital.[73]

Repeatedly during cluster munition attacks in Syria since 2012, and also in other countries prior to entry into force of the convention in 2010, civilian casualties during attacks hitting hospitals, markets, and schools have been widely reported as a horrific trend in cluster munition use.[74]

Casualties from cluster munition remnants

Cluster munition remnants pose an ongoing threat. Regardless of the time since they were used, unexploded submunitions and bomblets disproportionally harm civilians, including children. In 2020, cluster munition remnants caused 218 casualties, killing 63 people and leaving 144 injured. The outcome for 11 casualties was not recorded.

Afghanistan recorded three cluster munition remnants casualties in one incident.

Cambodia recorded one cluster munition remnant casualty in 2020; the first since 2017.

Iraq reported 31 cluster munition remnants casualties in 2020; a substantial rise from 20 during 2019, and the highest annual number recorded in Iraq since 2010.

Lao PDR recorded eight cluster munition remnants casualties in 2020; an increase from five in 2019, but still a significant reduction from the 51 casualties recorded in 2016.

South Sudan recorded 16 cluster munition remnants casualties in 2020, the highest since 2010.

In Syria, 147 cluster munition remnants casualties were recorded in 2020, a clear indication of the ongoing impact of recent contamination.

In Yemen, 11 cluster munition remnants casualties were recorded in 2020; yet substantial challenges with data collection indicates that casualties were significantly under-reported.

In the area of Nagorno-Karabakh, one unexploded submunition casualty was recorded in 2020, prior to the conflict. In 2021, at least two incidents from new cluster munition remnants contamination had been recorded by July.

Lebanon reported no cluster munition remnants casualties in 2020, making it the first year without such casualties since before the entry into force of the convention.

Cluster munition remnants casualties were recorded in Serbia in 2019, but not in 2020.

The area of Western Sahara did not record any cluster munition remnants casualties in 2020, but recorded a casualty in early 2021.

Cluster munition remnants contamination significantly impacts children, who made up nearly half (47%) of cluster munition remnants casualties globally in 2020.[75]

Cluster munition casualty demographics

Civilians accounted for all casualties who had their status recorded in 2020, while no military or deminer casualties were reported. The civilian status was unknown for 99 casualties.

A very high ratio of civilian casualties corresponds with findings based on analysis of historical data on cluster munition casualties. This consistent and foreseeable disproportionate impact on civilians is due to the indiscriminate and inhumane nature of these weapons.

2020 casualties by age group

Children accounted for 44% of all cluster munition casualties where the age group was reported in 2020.[76] The average age of child casualties in 2020 was 11 years old. Thirty of the children were under 10 years old, with the youngest recorded casualty being just two years of age. Among the child casualties in 2020, 73% were boys and 27% were girls.

2020 casualties by sex

Almost a quarter of all casualties were recorded as ‘female’ where the sex was known (24%, or 54 of 227).[77] Among those casualties, 43% were girls and 57% were women. Among casualties recorded as ‘male,’ the ratio of children to adults was lower, as 36% were boys and 64% were men. There was a significant difference in survival outcome in relation to the sex of casualties. Just under a third (32%) of male casualties were killed, but half of female casualties were killed.

Coordination, strategies, and planning

Clearance

Strong coordination is an important aspect of national ownership of mine action programs, enabling efficient and effective operations. In 2020, clearance programs in eight States Parties with remaining contamination—Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia—were coordinated through national mine action centers. In States Parties Chile and Germany, where cluster munition contamination is found on former military bases, the defense ministries are responsible for coordinating clearance. In both Croatia and Montenegro, mine action management functions were incorporated under departments within their respective ministries of interior.[78]

In States Parties with more complex and widespread contamination, planning and management functions are decentralized to regional mine action centers. In Iraq, the Directorate of Mine Action (DMA), which coordinates and manages the mine action sector in Federal Iraq, has three regional mine action centers covering the North, Middle Euphrates, and the South.[79] Regional Mine Action Center (RMAC) South, based in Basrah, is responsible for the clearance of the majority of cluster munition remnants in Iraq, with over 90% of contaminated land under its responsibility.[80]

In Somalia, a lack of government funding has weakened the ability of the Somali Explosives Management Authority (SEMA) to take on its coordination and management role.[81] Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) and the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) have supported SEMA with salaries and operational incentives.[82]

One of the guiding principles and actions of the draft Lausanne Action Plan is for States Parties to develop evidence-based, costed, and time-bound national strategies and workplans.

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Croatia, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia had a mine action strategy or plan in place in 2020, but not all included reference to cluster munition contamination survey and clearance.

BiH's National Mine Action Strategy for 2018–2025 was adopted in January 2019 and addresses all contamination in BiH, including landmines and cluster munition remnants. Lebanon has a new Humanitarian Mine Action Strategy for 2020–2025, which includes an objective to release all cluster munition contaminated areas by 2025.[83] A strategy implementation plan has also been elaborated and an annual workplan should be developed in 2021.[84]

In 2020, Afghanistan, Lao PDR, and Iraq were all in the process of developing new strategic plans. Afghanistan was developing a new five-year plan, focusing on all explosive ordnance, supported by the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD).[85] Lao PDR was elaborating a long-term national strategic plan to 2030, expected to be finalized in mid-2021.[86] The National Regulatory Authority for the UXO/Mine Action Sector in Lao PDR (NRA) was also developing a new five-year implementation plan, covering 2021–2025.[87] In Iraq, the DMA and the Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA) were working on a new strategic plan for 2022–2028, supported by GICHD and UNMAS, but the focus was primarily to reflect new priorities arising from the mine contamination that occurred during the conflict with the Islamic State.[88]

Chile has still to develop a workplan for the clearance of cluster munitions. It stated that this would be developed following the implementation of technical survey during 2021.[89]

Somalia reported in July 2021 that there was no plan for the clearance of cluster munition remnants on its territory.[90] Its mine action strategy expired at the end of 2020.

Risk education

In 2020, 10 States Parties had institutions in place as risk education focal points: Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Chile, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia. In Afghanistan, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon, risk education coordination mechanisms were in place; but in 2020, meetings were either irregular or were held remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In most cases, the risk education program is coordinated by the respective national mine action center. For school-based programs in Chile, Iraq, and Lao PDR, the education ministry in each country takes on a coordination role.[91] In Croatia, the former risk education department of the Croatian Mine Action Centre was transferred in 2019 to the National Education Center in the Civil Protection Directorate, within the Ministry of Interior.[92]

Risk education is included within the national mine action strategies of Afghanistan, BiH, Lao PDR, and Lebanon, although the extent to which risk education goals and activities are defined is frequently limited.

Lebanon’s strategy includes no specific risk education objective or output, with the exception that all community liaison, risk education and non-technical survey teams should be gender-balanced.[93] However, Outcome 1 of the strategy ensures that all affected individuals and communities should receive risk education and notes that refugees from Syria have special risk education needs.[94] Lebanon’s 2021 annual risk education workplan was developed in 2020, in consultation with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the United Nations (UN).[95]

In Lao PDR, the current national strategic plan, “Safe Path Forward II,” includes a sub-section on risk education.[96] The initial goal of reducing casualties from more than 300 to less than 75 per year has been achieved, and a more ambitious target of keeping annual casualties to fewer than 40 was agreed in 2015 during a review of the strategy.[97]

Victim assistance

In Afghanistan, no specific victim assistance coordination meetings took place in 2020 due to COVID-19 prevention measures and administrative challenges. However, the victim assistance department within the Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) actively participated in various other meetings on the rights of persons with disabilities.

In Lao PDR, the Victim Assistance Technical Working Group continued to hold meetings on a quarterly basis. In Lebanon, 10 meetings were held in 2020 and focused on organizing a national victim survey and classifying the data collected. Similarly, Somalia’s coordination efforts were carried out specifically to develop its victim assistance strategy. Albania and Iraq had ad hoc coordination processes in 2020, addressing specific needs as they arose.

In BiH, the recently formed victim assistance coordinating body had planned to hold quarterly meetings, but none were held in 2020 due to COVID-19 related measures. Similarly, Chad held no victim assistance coordination meetings in 2020. Croatia’s national victim assistance coordination body remained in hiatus, with its membership pending reappointment. Guinea-Bissau did not have any specific victim assistance coordination mechanism and lacked supporting legislation. Montenegro and Sierra Leone also had no coordination mechanism but had broader mechanisms on disability rights.

Among States Parties with cluster munition victims, all had a designated victim assistance focal point, except Sierra Leone, which has not provided a Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 transparency report since 2011.

As of the end of 2020, six of the States Parties with cluster munition victims had strategies or specific plans in place for victim assistance: Albania, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon. However, Chad’s National Plan of Action on Victim Assistance, adopted in 2018, has not been implemented.[98] Iraq’s plan, developed from the Iraq National Victim Assistance Dialogue held in 2018, was not implemented during 2020 due to the impact of COVID-19 restrictions.[99]

Two states had draft plans that were almost final and in the process of being officially adopted. Afghanistan and Somalia had each developed a new national disability strategy in 2019, with both strategies still pending formal approval as of the end of 2020.

Four of the States Parties with cluster munition victims did not have an active strategy or draft plan in 2020. Croatia has not replaced its Action Plan to Help Victims of Mines and UXO (unexploded ordnance), which expired in 2014. Guinea-Bissau presented a national victim assistance plan in 2013, which has long since expired.[100] Montenegro and Sierra Leone did not have a victim assistance plan in place, but both had a comparatively small number of recorded victims and managed broader disability legislation at the national level.

Mine action management and coordination

|

Coordination mechanism |

Clearance strategy/plan |

Risk education coordination |

Risk education strategy |

Victim assistance strategy/plan |

|

Afghanistan |

||||

|

Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) |

Mine Action Strategic Plan 2016–2020 (new strategy in development)

|

DMAC through RE-TWG |

Included in mine action strategy |

Disability strategy pending approval |

|

Albania |

||||

|

Albanian Mine and Munitions Coordination Office (AMMCO) |

N/A |

AMMCO |

N/A |

National Action Plan for Persons with Disabilities (NAPPD) 2016–2020 |

|

BiH |

||||

|

BiH Mine Action Center (BHMAC) |

National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025 |

BHMAC |

Included in mine action strategy |

Included in mine action strategy |

|

Chad |

||||

|

National Mine Action Authority in Chad (HCND) |

National Mine Action Plan 2020–2024 |

HCND |

None |

Plan adopted in 2018, but not implemented |

|

Chile |

||||

|

Ministry of National Defense |

Workplan to be developed based on technical survey |

Ministry of National Defense in coordination with Ministry of Education |

N/A |

None |

|

Croatia |

||||

|

Ministry of the Interior/Civil Protection Directorate |

National Mine Action Strategy 2020–2026 |

Ministry of the Interior through the Civil Protection Directorate and Police Directorate |

N/R |

None |

|

Germany |

||||

|

Federal Ministry of Defence |

Clearance workplan included within its 2019 extension request |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

||||

|

National Mine Action Coordination Centre (CAAMI) |

N/A |

CAAMI |

N/A |

None |

|

Iraq |

||||

|

Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) and Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA) |

National Mine Action Strategy 2017–2021 (under revision) |

DMA and Ministry of Education |

N/R |

Plan drafted in 2018 and adopted by DMA, but not implemented |

|

Lao PDR |

||||

|

National Regulatory Authority (NRA) |

Safe Path Forward II, 2011–2020 (new strategy in development) |

NRA through RE-TWG and Ministry of Education and Sports |

Included in mine action strategy |

UXO/Mine Victim Assistance Strategy 2014–2020 |

|

Lebanon |

||||

|

Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) |

Humanitarian Mine Action Strategy 2020–2025 |

LMAC through Risk Education Steering Committee |

Included in mine action strategy |

Humanitarian Mine Action Strategy 2020–2025 |

|

Mauritania |

||||

|

National Humanitarian Demining Programme for Development (PNDHD) |

Workplan included in its 2021 clearance extension request |

PNDHD |

None |

None |

|

Montenegro |

||||

|

Ministry of Internal Affairs, Directorate for Emergency Situations |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

None |

|

Sierra Leone |

||||

|

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

None |

|

Somalia |

||||

|

Somali Explosives Management Authority (SEMA) |

National Mine Action Strategic Plan 2018–2020 |

SEMA |

None |

Disability and victim assistance strategy pending approval |

Note: N/A=not applicable; N/R=not reported; RE-TWG=Risk Education-Technical Working Group; UXO=unexploded ordnance.

Data

Mine action data

Eight States Parties—Afghanistan, Chad, Chile, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia—use the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA), although not all contain accurate and up-to-date data.

BiH has its own database, with a specific database for cluster munition contamination. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is supporting a project funded by the European Union (EU), to improve information management in BiH through the development of an online database.[101]

The IMSMA system of the DMA in Iraq was updated in 2019 to provide an online operations dashboard, task management system, and online reporting tool (FIRST).[102] RMAC South, with support from the Information Management and Mine Action Programs (iMMAP), developed a field map application, offering high-resolution thematic spatial datasets for analysis.[103]

The IMSMA database of the NRA in Lao PDR is updated regularly and made publicly available online through a dashboard.[104]

In Lebanon in 2020, the Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC), with support from GICHD, had begun the process of data migration to IMSMA Core. The system was expected to be fully operational in 2021.[105]

The IMSMA databases in Chad, Mauritania, and Somalia are either older versions of IMSMA or not yet updated systematically.[106]

Germany uses its own information management system.[107]

Victim assistance data

In Afghanistan, the State Ministry for Martyrs and Disabled Affairs, with the support of the DMAC, was finalizing a national health and disability information system in 2020. The DMAC, with technical support from GICHD, also installed a new victim assistance database of which the pilot was being tested by three service provider organizations. Afghanistan also reviewed existing data and re-registered persons with war-related disabilities to provide them with pensions.[108]

BiH reported in 2020 that further survey was needed to establish detailed information on cluster munition victims, including those who had already been identified through initial survey.[109]

In Croatia, the Civil Protection Directorate, within the Ministry of the Interior, reported that data on landmine and explosive remnants of war (ERW) victims and family members was collated for a new victim database, as part of a four-year project funded by Switzerland.[110]

In Lao PDR, data on victims and services provided was available through the NRA’s online dashboard. The system is intended to help civil society organizations prepare their workplans and funding requests to address the needs of survivors.[111]

In Lebanon, LMAC undertook a national survey in 2020 to update data on mine/ERW victims, enabling the prioritization of victims for monthly financial support and rehabilitation services provided by the state.[112] This was the first national needs assessment reported since 2013.[113]

A mine/ERW victim census was planned in Chad to update the national database, while further survey was needed to identify cluster munition victims and/or needs in Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Montenegro, and Sierra Leone.[114] Mauritania and Zambia had yet to conduct initial surveys to identify or confirm whether they have cluster munition victims.

Integration of mine action into development goals and frameworks

Recognizing the impact of cluster munition contamination on sustainable development, several States Parties have considered integrating mine action into broader national development goals.

In Afghanistan, mine action is included in Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 15 and 16, related to the social protection sector. Afghanistan is also integrating mine action within other national development programs, including for agriculture, and has established agreements with other government ministries to enable cross-sectoral coordination. Afghanistan’s new five-year strategic plan will have objectives to boost advocacy and coordination for the role mine action plays as an enabler for sustainable development, peace, and human security.[115]

Chad’s National Mine Action Plan 2020–2024 is in line with the SDGs and with Chad’s National Development Plan 2017–2021, particularly in terms of allowing the safe return of populations to formerly contaminated areas.[116]

In 2020, Iraq was coordinating with the Ministry of Planning to include mine action in national development plans, poverty reduction strategies, and humanitarian response, in line with government priorities.[117]

In addition to having a specific goal, SDG-18, to address cluster munition remnants and ERW contamination, Lao PDR has included a specific output on clearance of contamination within its ninth National Socio-Economic Development Plan, for 2021–2025.[118] The plan provides a target to clear 10,000 hectares (100km²) of land per year for socio-economic development.[119] Lao PDR’s SDG-18 also includes a victim assistance target for 2030, aspiring to “Meet the health and livelihoods needs of all identified UXO survivors.”[120]

The preamble of the Convention on Cluster Munitions refers to the mission of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), “to ensure and promote the full realisation of all human rights and fundamental freedoms of all persons with disabilities.”

Among the 12 States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with cluster munition victims, all but Lebanon are also States Parties to the CRPD.

Lebanon has been a signatory to the CRPD since 2007, yet its 2011–2020 mine action strategy has the goal that the rights of victims are fulfilled “as per the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM) obligations, in the spirit of the Mine Ban Treaty (MBT), and in accordance with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).”[121]

Chad and Somalia ratified the CRPD in 2019, due to the efforts of organizations representing persons with disabilities[122]

In the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the SDGs are complementary to the victim assistance obligations of the Convention on Cluster Munitions and the CRPD, and present opportunities to bridge the overarching goals of relevant frameworks including peace, stability, and development (SDG-16) and to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing (SDG-3).[123]

Furthermore, in addition to including persons with disabilities in data collection and monitoring (SDG-17), persons with disabilities are referred to directly in several of the SDGs, including education (SDG-4), employment (SDG-8), reducing inequality (SDG-10), and accessibility of human settlements (SDG-11).

Standards

Survey and clearance

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia all had national standards in place consistent with the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS). However, the standards in Chad and Somalia do not include cluster munition remnants clearance and survey. Chile uses IMAS and a Joint Demining Manual for its armed forces, while clearance and survey in Germany are conducted according to federal legislation.

In Lao PDR, there are separate standards for unexploded ordnance (UXO) clearance operations and mine clearance operations.[124]

In 2020–2021, national mine action standards in Iraq were being reviewed and updated with the support of UNMAS.[125] Lebanon also conducted a full review of its national standards in 2020.[126] Mauritania plans to conduct a review of its standards during its requested two-year Article 4 extension period from 2022–2024.[127]

Some States Parties developed COVID-19 prevention and control guidelines for mine action operations during 2020, for example Afghanistan and Iraq.[128]

Risk education

Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon all have national standards in place for risk education. BiH also has an accreditation guide for risk education organizations.[129]

Both Lao PDR and Lebanon reported that they were planning to update their risk education standards in line with the second edition of IMAS 12.10 on Explosive Ordnance Risk Education from September 2020.[130]

Chad plans to update its national standards for risk education in 2022.[131]

Victim assistance

The first specific draft IMAS on victim assistance was developed in 2018–2019. IMAS 13.10 on Victim Assistance was in the process of approval as of July 2021.The draft IMAS on victim assistance noted that the mine action sector, under the governance of national mine action authorities, is well placed to gather information about victims and their needs, to provide information on services, and refer victims to government bodies for support. According to the draft IMAS, national mine action authorities and mine action centers can, and should, “play a role in monitoring and facilitating the ongoing, multi-sector efforts to address the needs of victims,” and help in “ensuring the inclusion of survivors and indirect victims, and their views in the development of relevant national legislation and policy decisions.”[132]

Both Iraq and Lao PDR demonstrated their interest in the draft and are positioned to become the first adopters of national standards aligned with IMAS 13.10. In 2020, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and Humanity & Inclusion (HI), held meetings with Iraq’s DMA on preparing a national standard for victim assistance and on the mechanism for collecting standardized victim data.[133] In Lao PDR, the NRA, which already has a National Standard on UXO and Mine Victim Assistance, planned to update its standards in line with IMAS 13.10 in 2021, with the support of HI.[134]

Gender and diversity

Delivering mine action with inclusive, equal, and meaningful gender-balanced participation is a guiding principle of the draft Lausanne Action Plan. Afghanistan, BiH, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon have all made substantial efforts to include gender and diversity considerations within their mine action programs.[135]

Both DMAC in Afghanistan, and the DMA in Iraq, have established specific departments to oversee gender mainstreaming.[136]

The NRA in Lao PDR adopted a Gender Equality Strategy in 2011, while the 2014 decree on the establishment of the NRA made the Lao Women’s Union (LWU) a board member.[137]

In 2018 and 2019, the LWU was the main partner on gender training alongside the NRA and UN Women.[138]

BiH and Lebanon have included gender and diversity within their mine action strategies.[139]

Cluster munition remnants clearance

Obligations regarding clearance

Under the Convention on Cluster Munitions, each State Party is obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under its jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention. If unable to complete clearance on time, the State Party may request deadline extensions for periods of up to five years.

Reporting

As of 1 August 2021, nine States Parties with clearance obligations had submitted their Article 7 transparency reports for calendar year 2020: Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Chile, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mauritania submitted their Article 7 transparency reports on or before 30 April 2021.[140] Somalia had not yet submitted its report.

Clearance in 2020

In 2020, States Parties reported clearing more than 63km² of cluster munition contaminated land, a decrease from 82km² in 2019. At least 80,925 cluster munition remnants were cleared and destroyed in 2020.

The Monitor data on cluster munition clearance in States Parties is based on analysis from information provided by a range of sources including reporting by national mine action programs, Article 7 transparency reports, and Article 4 extension requests. In cases where varying annual figures are reported by States Parties, details are provided in footnotes and more information can be found in country profiles on the Monitor website.

Cluster munition remnants clearance in 2019–2020[141]

|

State Party |

2019 |

2020 |

||

|

Clearance (km²) |

CMR destroyed |

Clearance (km²) |

CMR destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

2.72 |

86 |

0 |

276 |

|

BiH |

0.72 |

85 |

0.34 |

162 |

|

Chad |

4.33 |

18 |

0.41 |

9 |

|

Chile |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Croatia |

0.04 |

186 |

0.03 |

11 |

|

Germany |

1.21 |

1,814 |

1.08 |

971 |

|

Iraq |

6.29 |

9,996 |

5.67 |

6,146 |

|

Lao PDR |

64.95 |

80,247 |

54.32 |

71,235 |

|

Lebanon |

1.26 |

4,037 |

1.28 |

2,098 |

|

Mauritania |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Montenegro |

0.78 |

64 |

0.25 |

15 |

|

Somalia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

TOTAL |

82.30 |

96,533 |

63.38 |

80,925 |

Note: CMR=cluster munition remnants.

As in previous years, Lao PDR cleared the most land—54.32km² in 2020—representing 86% of the overall total. This included 42.04km² of agricultural land and 12.28km² of land intended to be used for development.[142] In total, 71,235 cluster munition remnants were destroyed.[143] More than four-fifths (85%, 46.01km²) of clearance in Lao PDR in 2020 was undertaken in the nine most heavily contaminated provinces.[144] However, 18% of the total cleared—amounting to 9.61km² of land cleared by commercial operators for development purposes—did not contain any cluster munition remnants. Some of these areas contained other types of ERW.[145]

Iraq reported clearing 5.67km² of cluster munition contaminated land in 2020. In total, 14.07km² of land was released, with 6.58km² through technical survey and 1.82km² through non-technical survey.[146] Iraq cleared 6,146 cluster munition remnants; 5,826 through battle area clearance and 320 through technical survey.[147] The majority of this clearance took place in the south, with limited non-technical survey conducted in the north.[148]

Lebanon reported the release of 1.59km² of cluster munition contaminated land in 2020. Of this total, 1.28km² was cleared, 0.28km² was cancelled through non-technical survey and 0.03km² was reduced through technical survey.[149] A total of 2,098 cluster munition remnants were cleared and destroyed in 2020 through surface and sub-surface clearance and rapid response.

Germany cleared 1.08km² of cluster munition contaminated land in 2020, destroying 971 cluster munition remnants. Since 2017, a total of 4km² has been cleared in Germany; 3.53km² within areas of suspected cluster munition contamination, and 0.47km² outside these areas.[150]

BiH reported cluster munition land release of 0.68km² in 2020, including 0.34km² through clearance and 0.34km² through technical survey, resulting in the destruction of 162 cluster munition remnants.[151]

Chad reported clearing 0.41km² of cluster munition contaminated land in Delbo village, West Ennedi province, in 2020. Nine cluster munition remnants were reported cleared and destroyed.[152]

Completing their clearance obligations in 2020, Montenegro cleared 0.25km², while Croatia cleared 0.03km² of cluster munition contaminated land.

No clearance of cluster munition contaminated land was reported in four States Parties in 2020.

Afghanistan reported no clearance of cluster munition remnants in 2020 due to unavailability of funding. However, 276 cluster munition remnants were cleared and destroyed during explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) operations, including 11 BLU-97 submunitions found in Deh-Sabz district of Kabul province.[153]

Chile had planned to conduct technical survey in 2020, to identify the precise perimeter of its contaminated areas. However, survey was delayed due to a lack of resources and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis response.[154]

Mauritania announced previously unreported contamination identified in 2019 located in the region of Tiris Zemmour in the north, bordering Western Sahara. An initial assessment of contaminated areas took place in February 2021 to determine whether the areas found are under Mauritania’s jurisdiction and control.[155]

Somalia reported no clearance in 2020, although two submunitions were found and destroyed during battle area clearance in Bakol.[156]

Article 4 deadlines and extension requests

If a State Party believes that it will be unable to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants on its territory within 10 years of the entry into force of the convention for the country, it is able to request an extension to its deadline for a period of up to five years.

The first extension requests were submitted for consideration at the Ninth Meeting of States Parties in September 2019. In 2019, Germany and Lao PDR were each granted five-year extensions to their Article 4 deadlines. BiH, Chile, and Lebanon submitted requests in 2020, which were all granted in 2021 via silence procedure.

In 2021, Chile submitted a second request and Mauritania submitted an extension request based on the new contamination found.

Status of Article 4 progress to completion

|

State Party |

Original deadline |

Extension period (year granted) |

Current deadline |

Expectation to meet deadline |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2022 |

Extension request submitted in 2021 |

1 March 2022 |

Requested 4-year extension until 2026 |

|

BiH |

1 March 2021 |

18 months (2021) |

1 September 2022 |

Expects to complete in 2022 |

|

Chad |

1 September 2023 |

N/A |

1 September 2023 |

Expects to complete before 2023 |

|

Chile |

1 June 2021 |

1 year (2021) 2nd extension request submitted in 2021 |

1 June 2022 |

Expects to complete in 2025

|

|

Germany* |

1 August 2020 |

5 years (2019) |

1 August 2025 |

Expects to complete in 2024 |

|

Iraq |

1 November 2023 |

N/A |

1 November 2023 |

Unlikely to meet deadline |

|

Lao PDR |

1 August 2020 |

5 years (2019) |

1 August 2025 |

Unlikely to meet deadline |

|

Lebanon |

1 May 2021 |

5 years (2021) |

1 May 2026 |

Expects to complete by 2025 |

|

Mauritania |

1 August 2022 |

Extension request submitted in 2021 |

1 August 2022 |

Requested 2-year extension until 2024 |

|

Somalia |

1 March 2026 |

N/A |

1 March 2026 |

Unknown |

Note: N/A=not applicable.

* Clearance in Germany is expected to be completed at the end of 2024, with final reporting and documentation completed in 2025.

BiH, Chad, Germany, and Lebanon should all be able to complete clearance within the period of their current Article 4 deadlines.

In 2020, BiH submitted an 18-month extension request to complete clearance by 1 September 2022.[157] BiH has indicated to the Monitor that it expects to meet its deadline.[158]

Chad reported in 2020 that it was in the process of clearing the last known area contaminated with cluster munition remnants, and that clearance would be completed by the end of July 2021, before their 2023 deadline.[159]

In its 2019 extension request, Germany reported that it should be able to complete clearance of the Wittstock military training area by 2024; and has since stated that it was confident that by 2025, Germany would be cluster munition free.[160] Germany has a time-bound plan, that estimates clearance of 1.5km² to 2km² per year by 2024.[161] In 2021, Germany was to tender for three companies to continue clearance, employing 180–200 people on a permanent basis. Germany reported that the COVID-19 pandemic did not lead to any impairment in clearance activities in 2020.[162]

In 2021, Lebanon was granted five additional years, to 1 May 2026, to meet its clearance obligations. The Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) provided a detailed plan based on available assets, and despite challenges related to terrain, believes that it should be able to meet its 2026 deadline.[163]

Three States Parties submitted extension requests in 2021.

Afghanistan initially reported that it would meet its clearance deadline of 1 March 2022 as there was commitment from some donors—the US State Department Bureau of Political-Military Affairs’ Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement (PM/WRA) and the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS)—to support the clearance of 10 remaining areas.[164] However, discovery of additional contaminated areas and a change in donor commitments led Afghanistan to submit an extension request in August 2021, requesting four additional years until March 2026.[165] A major challenge to clearance in Afghanistan is the control of areas by the Taliban and other non-state armed groups (NSAGs).

Chile has made little progress on clearance, despite having been a State Party to the convention since December 2010. In January 2020, Chile submitted an extension request for a period of five years until 2026.[166] In June 2020, the request was revised to a one-year interim extension, to conduct technical survey and submit a later extension request with a clearance plan.[167] The request was granted through silence procedure in May 2021. In June 2021, Chile submitted a second one-year extension request, without survey having been undertaken, citing a lack of resources in addition to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.[168]

In June 2021, Mauritania submitted a request for a two-year extension, until 1 August 2024, to complete survey and clearance.[169]

The requests from Afghanistan, Chile, and Mauritania will be considered by States Parties at the Second Review Conference of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in September 2021.

It is unlikely that Iraq and Lao PDR will meet their current clearance deadlines.

Iraq reported that it is unlikely to meet its deadline of 2023, and that with its clearance capacity, it would require at least 15 more years.[170] The Regional Mine Action Center (RMAC) South reported that challenges for clearance of cluster munition remnants include the fact that national efforts are focused primarily on areas liberated from the Islamic State, while new contaminated areas continue to be found through survey, particularly in the southern provinces.[171]

Lao PDR has indicated that completion of survey would be a priority during its extension period, with an expectation that additional international support would be needed.[172]

It is unknown whether Somalia will meet its clearance deadline of 1 March 2026. Somalia does not have an accurate picture of contamination and has no plan in place for clearance.

Obligations regarding risk education

Article 4, paragraph 2 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions states that each State Party shall “conduct risk reduction education to ensure awareness among civilians living in or around cluster munition contaminated areas of the risks posed by such remnants.”

Risk education in the context of the convention encompasses interventions aimed at protecting civilian populations and individual civilians, at the time of use of cluster munitions, when they fail to function as intended, or when they have been abandoned.

Reporting

States Parties have an obligation to report on risk education activities.[173] According to the draft Lausanne Action Plan, states will commit to provide data on beneficiaries of risk education disaggregated by gender, age, and disability in their annual transparency reports. In 2021, Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mauritania reported on risk education in their annual Article 7 reports covering calendar year 2020. Somalia did not submit its annual report in 2021. Chile and Germany stated that risk education was not applicable due to contamination being confined to military training areas.

Afghanistan, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon provided detailed information on risk education efforts. BiH, Chad, and Mauritania provided limited information.

Chad, Iraq, and Lebanon provided beneficiary figures for 2020 disaggregated by age and sex, while Lao PDR provided figures disaggregated by sex but not age.

No State Party reported on persons with disabilities being reached by risk education.

Risk education for cluster munition contamination

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon all reported conducting risk education covering the threat posed by cluster munition remnants in 2020.

In Lao PDR, risk education is specifically directed to addressing the risk behaviors associated with cluster munition remnants.

In other States Parties where cluster munition remnants contamination is mixed with other forms of mine/ERW contamination which may be more predominant, risk education operators do not conduct specific sessions related to cluster munition remnants.

In Somalia, cluster munition remnants are not included on risk education materials due to there being little evidence of contamination.[174]

Risk education targeting

The development of context-specific, tailored risk education activities requires the availability of comprehensive victim data.[175] National-level Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) data is used in Afghanistan, Lao PDR, and Lebanon to inform the targeting of risk education.[176]

Afghanistan maintained a priority scoring matrix to prioritize the most affected populations in terms of proximity to hazards, recent casualty figures, and incidences of armed conflict.[177] In Lebanon, priorities for risk education are set according to the size of the local population, the number of incidents and casualties, and the extent of contamination in the area.[178]

In BiH and Iraq, it was reported that victim databases are often incomplete and, in the case of Iraq, not openly available for interrogation.[179] In Iraq, operators relied on their own analysis of victim data in their areas of operation. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the Iraq Red Crescent Society (IRCS) were also reported to have compiled and shared victim data with some operators.[180]

In 2020, children continued to be a high-risk group with regard to cluster munition remnants. In Lao PDR, children are known to be tempted to pick up and play with submunitions because of their size and shape.[181] In Lebanon, parents were targeted for risk education, to pass messages on to their children.[182]

In BiH, targets for risk education are prioritized based on age, gender, cultural habits, and areas with the heaviest contamination.[183] Incidents in BiH occur most frequently during spring and autumn, and among men in agricultural communities.[184] In Lao PDR, men often enter contaminated areas knowingly, out of economic necessity. In both BiH and Lao PDR, familiarity with contamination encourages misplaced confidence.[185] In Lao PDR, high-risk activities, such as foraging on contaminated land or lighting fires directly on the ground surface, continue to pose a risk and result in cluster munition incidents.[186]

In Lebanon, Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) held risk education sessions for landowners, land users, and municipal officials in cluster munition contaminated areas.[187] The 1.5 million refugees from Syria hosted in Lebanon are regarded as a priority group due to their unfamiliarity with the contamination, and the close proximity of refugee camps and settlements to hazardous areas.[188]

In southern Iraq, nomadic communities are particularly at risk from cluster munition remnants. The Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) developed an intensive awareness campaign, implemented in 2020, for the Bedouin people in the Samawah Badia desert, Al-Muthanna governorate, following a rise in accidents during the spring when Bedouins gather to graze livestock and plant crops.[189] Tourism seasons in Wassit and Missan governorates, and also the grazing, transportation, and hunting seasons in Al-Muthanna governorate, were a focus of risk education campaigns in 2020.[190]

In Chad, nomads, animal herders, traditional guides, and trackers remained high-risk groups due to their movement through desert areas which may have contamination. However, these groups are challenging to reach for risk education because they are mobile.[191]

Efforts were made in 2019 and 2020 to better incorporate the needs of persons with disabilities into risk education. In Iraq, Humanity & Inclusion (HI) provided community focal points with training on inclusion awareness and positive disability inclusion messages, and training on how to refer persons with disabilities and mental health issues to relevant services.[192] HI was integrating victim assistance and risk education across their programs as part of its comprehensive approach, and also incorporated sign language and subtitles into a risk education video.[193] UNMAS Iraq reported that it was collecting disability disaggregated data to inform risk education.[194]

In Lao PDR, risk education is almost exclusively conducted in remote rural areas, particularly in ethnic minority villages and along the route of the former Ho Chi Minh trail, near the border with Vietnam. Challenges for operators include accessing remote areas and ensuring that risk education messages are understood by groups speaking different languages and dialects.[195]

Risk education delivery

Risk education was integrated with survey and clearance in States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon.[196]

Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon reported having free phone numbers for the public to call to report any ordnance found.[197] In Lebanon, the number is shared with local communities via SMS text messaging as part of the national risk education campaign.[198]

The training of local committees and community volunteers as focal points to deliver risk education messages was reported in Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon. These focal points also supported data collection and the reporting of ERW.[199] In Chad and Lao PDR, local risk education volunteers provided messages in regional dialects or minority languages.[200]

Risk education is integrated into the primary school curriculum from grades 1 to 5 in Lao PDR, across 10 of the country’s 18 provinces.[201] Lebanon implements risk education in educational institutions nationwide, as part of the school health curriculum.[202] In 2020, LMAC, alongside the Ministry of Education and Higher Education, organized a risk education training of trainers program in public schools as part of broader health and safety training for teachers.[203]

Risk education took place in schools in Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lebanon, and Somalia in 2020, but not as part of the formal curriculum.

In BiH, risk education was included in the informal curriculum at primary level, with materials provided to teachers; while the Red Cross Society also conducted risk education in schools via their “Think Mines” project.[204] In Chad, Mines Advisory Group (MAG) and HI provided risk education sessions in schools located near hazardous areas.[205] In Iraq, the DMA was working with the Ministry of Education to integrate risk education into the school curriculum for grades 5 and 6, and was developing plans to train groups of teachers in risk education delivery.[206] In Afghanistan, the Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) was coordinating the use of child-focused risk education materials, which were developed in 2020.[207]

Innovative delivery methods were reported in 2020. In BiH, a free android phone app—“BH mine suspected areas” developed with the support of UNDP—was promoted by BiH Mine Action Center (BHMAC). The app provides notifications and risk education messages if the user is near a minefield. It also enables the user to make an SOS call or take a picture of a suspicious object to send to the authorities.[208]

In Lebanon, LMAC worked with MAG to develop a virtual reality risk education video.[209]