Landmine Monitor 2010

Casualties and Victim Assistance

© Giovanni Diffidenti, November 2009

A survivor undergoing physical rehabilitation in Colombia.

Casualties in 2009 [1]

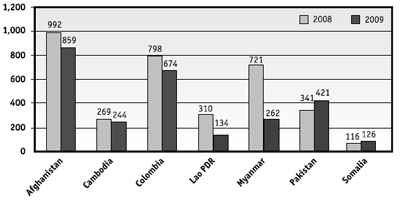

The Monitor identified 3,956 casualties occurring in 2009 that were caused by mines, victim-activated improvised explosive devices (IEDs), cluster munition remnants, and other explosive remnants of war (ERW) in 64 states and areas.[2] At least 1,041 people were killed, 2,855 were injured, and the status of 60 casualties was unknown.[3] As in 2008, Afghanistan had the greatest number of casualties (859), followed by Colombia (674). Despite decreasing casualty figures, in part due to successful clearance and awareness-raising, many thousands of people face the risk of injury from mines, ERW and, increasingly, IEDs while trying to carry out their daily activities.

States with 100 casualties or more in 2009

|

State |

No. of casualties in 2009 |

|

Afghanistan |

859 |

|

Colombia |

674 |

|

Pakistan |

421 |

|

Myanmar |

262 |

|

Cambodia |

244 |

|

Lao PDR |

134 |

|

Somalia |

126 |

The region with the greatest number of casualties by far was Asia-Pacific.

2009 casualties by region

|

Region |

No. of casualties |

No. of states and areas in the region with casualties |

|

Asia-Pacific |

2,153 |

13 |

|

Americas |

682 |

4 |

|

Africa |

534 |

19 |

|

Middle East-North Africa |

324 |

13 |

|

Europe and CIS |

263 |

15 |

|

Total |

3,956 |

64 |

It needs to be stressed that the 3,956 figure only includes recorded casualties and, due to incomplete data collection, the true casualty figure is definitely higher.

The 2009 figure represents by far the lowest number of recorded casualties worldwide since the Monitor began reporting in 1999 and it is the first time the global casualty figure has fallen below 5,000.[4] This decline is, in part, a continuation of a steady global decline in mine/ERW casualties; the continued trend of decreasing casualties in Colombia is one of the major contributors to this global decline. Also, in 14 of the states that recorded casualties for 2008, no casualties were identified for 2009.[5] Two states that did not report casualties in 2008 reported casualties in 2009: Albania and Mauritania.

However, the decline can in large part be attributed to a decline in availability of casualty data for 2009 in various countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Lao PDR, and especially in Myanmar where in 2008 one-off information on military casualties resulted in 508 additional reported casualties (which is 12% of the 2009 casualty total). In some cases, data collection is severely hindered by conflict, such as in Pakistan, where the Monitor needs to rely on media reports, and likely also in Afghanistan, where the mine action center recorded significantly fewer casualties in 2009 compared to previous years.

Total mine/ERW casulaties for most affected countries: 2008-2009

Casualty demographics

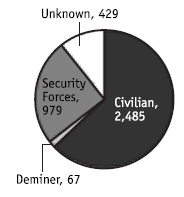

In 2009, civilians made up 70% of all casualties for which the civilian/military status was known (2,485 of 3,531).[6] This was an increase from 2008 when civilians made up 61% of all casualties, though it was nearly identical to the proportion of civilian casualties in 2007 (71%). However, this fluctuation can mainly be attributed to one-time information on military casualties in Myanmar available for 2008 which included a number that was significant enough to affect the global proportion of civilian to military casualties.[7] The vast majority (80%) of military casualties for 2009 were identified in just three states, where there was ongoing armed conflict/violence: Colombia (442), Afghanistan (237), and Pakistan (103).

Mine/ERW casulaties by civilian/military status 2009

There were 67 casualties among humanitarian deminers in 14 states/areas[8] in 2009, a 30% decrease compared to 2008, when there were 96 deminer casualties. As in 2008, by far the most clearance casualties occurred in Afghanistan (34 casualties), followed by Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Cambodia, and Yemen, each with five. In each of these states, the number of casualties among deminers declined from 2008.[9] One female demining casualty was recorded in Cambodia.[10]

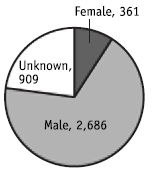

As in previous years, the vast majority of casualties where the gender was known were male (2,686 of 3,047, or 88%), and 361 (or 12% of casualties) were female, which is a small increase compared to 2008.[11] Among civilian casualties for whom the gender was known, female casualties made up 16% of the total (336 of 2,081). In 2009, there were no states where girls and/or women were the majority of casualties, though female casualties increased as a proportion of total casualties in seven states.[12]

Casulaties by gender: 2009

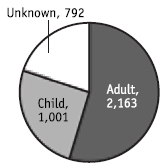

Children made up almost a third of all casualties for whom the age was known (1,001 of 3,164)—a slight increase from 2008. For 20% of casualties (792) information about their age was unknown, which was nearly the same as in 2008. When looking only at civilian casualties for whom the age was known, children made up nearly half of all casualties, 45% compared to 41% in 2008. The vast majority of child casualties were boys (73%, equal to 2008), 18% were girls (up from 16% in 2008), and the gender of 72 child casualties was not recorded.

In 11 states/areas, children made up half or more of all civilian casualties, including in Afghanistan, with 288 child casualties, and Chad, where children made up 95% of all casualties.[13] In the Philippines, child casualties, accounting for more than 50% of all casualties, were identified for the first time since 2005. In BiH, the number of child casualties was the highest since 2004. In Eritrea, while overall casualty figures decreased significantly in 2009, the number of child casualties remained consistent and increased from 50% of civilian casualties in 2008 to 76% in 2009.

Casualties by age: 2009

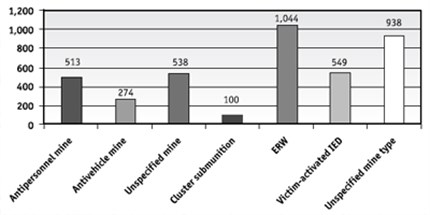

Items causing casualties

In 2009, for 24% of all casualties (938), the item that caused the casualty was unknown.[14] For 3,018 casualties, the item type was known. Of these:

- Mines, including antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, and mines of unspecified types were the most common, at 1,325 (44% of the 2009 total), a slight decrease as compared to 2008:

- antipersonnel mines caused 513 casualties (17% of the 2009 total), a continued decrease from 2008 and 2007;[15]

- unspecified types of mines caused 538 casualties (18% of the 2009 total), a continued increase from 2008 and 2007; and

- antivehicle mines caused 274 casualties (9% of the 2009 total), down from 2008 and 2007.[16]

- ERW, including cluster munition remnants, caused 1,144 (or 38%), compared to 44% in 2008:

- cluster munition remnants caused 100 casualties (3% of the 2009 total), a decrease from 2008 and from 2007; and

- ERW caused 1,044 casualties (35% of the 2009 total), down from 2008 but similar to the 2007 level.[17]

A sharp increase in casualties from victim-activated IEDs, which function like de facto antipersonnel mines, is the main reason for the decreased proportion of mine and ERW casualties. Victim-activated IEDs caused 549 or 18% of casualties in 2009 (where the device type was known), compared to less than 3% in 2008 and 10% in 2007. This increase is explained by the leaking of a new source of detailed information on IED casualties in Afghanistan in 2009.[18] Some 293 victim-activated IED casualties were identified for Afghanistan in 2009, compared to just three in 2008, accounting for more than 50% of worldwide victim-activated IED caualties in 2009.[19]

Casualties by item: 2009

States/areas with casualties, by item type where known[20]

|

Item type |

State/area with casualties in 2009 |

|

Antipersonnel mines |

Abkhazia, Afghanistan, Angola, Azerbaijan, BiH, Cambodia, China, Colombia, Croatia, India, Iraq, Israel, South Korea, Lebanon, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Senegal, Somaliland, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Thailand, Western Sahara, and Yemen. |

|

Antivehicle mines |

Abkhazia, Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Cyprus, Mauritania, Nagorno-Karabakh, Niger, Pakistan, Russia, Somaliland, Sri Lanka, Syria, Western Sahara, and Yemen. |

|

Unspecified mine type (antipersonnel or antivehicle) |

Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, India, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Myanmar, Niger, Philippines, Somalia, Turkey, Western Sahara, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. |

|

ERW |

Abkhazia, Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Azerbaijan, Belarus, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), El Salvador, Eritrea, Georgia, Guinea-Bissau, India, Iraq, Jordan, Kosovo, Kuwait, Lao PDR, Mali, Lebanon, Mozambique, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Palestine, Philippines, Russia, Somalia, Somaliland, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Vietnam, Western Sahara, Yemen, and Zambia. |

|

Submunitions |

Afghanistan, BiH, Cambodia, DRC, Iraq, Kosovo, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Sudan, and Vietnam. |

|

Victim-activated IEDs |

Afghanistan, Cambodia, Colombia, DRC, India, Iraq, Nepal, Pakistan, and Peru. |

Note: Other areas are indicated by italics.

As in 2008, where age was known, most antipersonnel mine casualties were adults (87%, up from 80% in 2008), and nearly all of those (91%) were men.[21] Antipersonnel mines caused two-thirds (or 44 of 67) of all demining casualties, but just 53 military casualties (5%).[22]

In 2009, 64% of casualties caused by unexploded submunitions were adults, and 36% were children (when the age of the casualty was known), compared to a 50-50 ratio in 2008. When looking at all other types of ERW, children constituted 61% of casualties where the age was known (582 of 953), compared to 57% in 2008. When the gender was known,[23] boys were the largest casualty group at 49% (up from 45% in 2008). Some 32% were men (down from 42%), 11% were girls (up from 9%), and 8% were women (up from 4%).

Victim Assistance

Introduction

In an otherwise mostly static year for service provision to survivors of landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW), the greatest change was seen in the international framework for responding to their needs, with three major developments.

First, States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty agreed to the Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 at the Second Review Conference in December 2009.[24] The Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009, the blueprint for the implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty since the First Review Conference in December 2004, reached its end. This prompted States Parties, NGOs, and international organizations to review progress made towards the plan’s commitments. They also assessed what actions were needed to ensure more effective implementation of victim assistance initiatives post-2010, resulting in the Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014.

Second, after entering into force on 3 May 2008, implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) began in several states with significant numbers of mine/ERW survivors. Finally, the entry into force of the Convention on Cluster Munitions on 1 August 2010, which includes strong victim assistance obligations as one of its central components, increased the standards for assistance to survivors, their families, and affected communities. Each of these instruments solidified legal obligations and commitments to survivors, making 2009 an important transitional year for the future orientation of victim assistance.

In the lives of most survivors, however, 2009 was much like previous years, with some progress but also persistent obstacles that varied for each state, program, and individual. Improvements in the quality and accessibility of services for survivors in 2009 were seen in a small number of countries. Unfortunately, nearly as many countries reported a decline in services, due mostly to changed security situations and global economic conditions.

In this reporting period, the Monitor profiled 56 countries[25] and six areas[26] with the largest number of mine/ERW survivors, providing a thorough picture of the victim assistance situation in 2009 in the context of the Mine Ban Treaty and other relevant legal instruments.[27] The Monitor measured progress in victim assistance in 2009 in four key areas:

- Survivors’ needs assessments, because the completeness of information on mine/ERW casualties, the needs of survivors, and existing services is essential to planning and implementing an effective victim assistance program that addresses survivors’ real needs.

- Victim assistance coordination includes the planning, monitoring, and coordination of all aspects of victim assistance, with all relevant stakeholders, such as government ministries, survivors and their representative organizations, and civil society actors.

- Survivor inclusion is meaningful, and that there is full participation of survivors and their representative organizations in all aspects of the Mine Ban Treaty (and other relevant legal mechanisms) and in all aspects of victim assistance decision-making, coordination, implementation, and monitoring.[28]

- Quality and accessibility of services means that a variety of services (including emergency and continuing medical care, physical rehabilitation, psychological support, and social and economic inclusion) are available and accessible and must meet minimum quality standards. Equal access should also be guaranteed by a national legal framework that promotes the rights of survivors and other persons with disabilities

Assessing the Survivors' Needs

The Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009 called on States Parties to “[d]evelop or enhance national mine victim data collection capacities” and to ensure access to data by relevant victim assistance stakeholders and service providers as a baseline for appropriate victim assistance. By the end of 2009, “many relevant States Parties still know little about the specific needs of survivors and the assistance received or needed.”[29] Just four of the 26 relevant States Parties reported that comprehensive information was available on the numbers and location of mine survivors to support the priority-setting of service providers and other victim assistance stakeholders.[30]

In the reporting period, only 14 of 62 countries and areas initiated and/or completed survivor surveys or needs assessments.[31] Seven of these were nationwide surveys[32] and the remainder were limited to a geographic area or time period.[33] In six states, collected data was used by victim assistance stakeholders for planning purposes and/or to improve referral of survivors to existing services.[34] In four other states, plans to use data to improve victim assistance had not yet materialized by the end of 2009.[35] In one state (BiH) data collected was not accessible to service providers.[36]

- In Algeria, the Interministerial Committee on the Implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty, in cooperation with the National Research Center in Social and Cultural Anthropology, completed a survey on the socio-economic impact of mines/ERW that included an assessment of survivors and victim assistance services. Full results were not yet available by the end of 2009.

- BiH completed a national casualty database revision and needs assessment started in 2008, though several key actors were unable to access the information and one service provider found the data to be inaccurate and requiring re-verification before use.

- The Network for Mine Victims in Mozambique, with support from the National Demining Institute, surveyed survivors and their needs in four districts in Maputo province. Consultations with the Ministry of Women and Social Action ensured that the results of the survey would be considered as admissible criteria to receive relevant government benefits.

- In Peru, the Peruvian Center for Mine Action worked with the National Council for the Integration of Disabled Persons and the National Institute of Rehabilitation to interview 99 of 117 registered civilian mine survivors in February 2010. The results were to be used to design a national victim assistance plan and refer survivors to available services.

- In Senegal’s Casamance region, a three-day casualty data verification and needs assessment of civilian mine/ERW survivors served as the basis for the National Victim Assistance Action Plan 2010–2014. Due to the short timeframe for the survey there were concerns about the comprehensiveness of the results.

In Angola and Croatia, steps were taken in 2009 to prepare survivor needs assessments launched in 2010. In Palestine and Nicaragua, surveys on the needs of persons with disabilities, including mine/ERW survivors were started in 2009. In Colombia, victim assistance services were mapped but no attempt was made to match these services with survivor needs.

Additionally, numerous NGOs and service providers continued to collect data on survivors’ needs and the services they had received. In several countries and areas, service providers reported ongoing collection of data on beneficiaries’ needs[37] and, in Serbia, the national survivors’ association, Assistance Advocacy Access, launched a national survivor needs assessment at the end of 2009.

However, recognizing that severe data collection challenges persisted, States Parties, at the end of 2009, committed under the Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 to “Collect all necessary data, disaggregated by sex and age, in order to develop, implement, monitor and evaluate adequate national policies, plans and legal frameworks”[38] and to be sure that such data includes information on both the needs of survivors and the availability of relevant services. This action also calls for “such data [to be made] available to all relevant stakeholders and that it contribute to other relevant, national data collection systems.”[39]

Victim Assistance Coordination

While the Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009 did not explicitly address issues related to the coordination of victim assistance, by the end of 2009, States Parties had to recognize that the most identifiable achievements since 2005 had been “process-related.”[40] The Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 underscored the importance of these organizational aspects by calling on States Parties to “Establish, if they have not yet done so, an inter-ministerial/inter-sectoral coordination mechanism for the development, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of relevant national policies, plans and legal frameworks…”[41]

Coordination mechanisms

The Monitor found that at least 19 states, about one-third of the profiled countries, had specific victim assistance coordination mechanisms.[42] One of these was officially initiated in 2009: in Uganda, the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development established a victim assistance coordination mechanism, which only met once. Also, in Colombia new thematic committees were created within the national mine action center’s existing victim assistance coordination mechanism to improve coordination, socio-economic reintegration, and psychosocial support.

In addition, two states started mine action coordination that included victim assistance in 2009. Eritrea re-initiated meetings of the Technical Working Group on the Mine Action Program which included victim assistance and the non-governmental Explosive Remnants of War Coordination Centre in Georgia included victim assistance among its coordination activities.[43]

Some countries made steps to integrate or transform victim assistance coordination into coordination for the broader disability sector.

- Afghanistan’s disability sector coordination mechanism, which also covers victim assistance, improved and expanded by establishing two new regional stakeholder coordination groups in addition to the existing group in Kabul.

- In Cambodia, the Steering Committee for Landmine Victim Assistance was in a process of transformation into a National Disability Coordination Committee (NDCC), with a broader coordination role for the disability sector.[44]

- In Jordan, responsibility for victim assistance was assumed by the Higher Council on the Affairs of Persons with Disabilities which formally established a Steering Committee on Survivor and Victim Assistance. Victim assistance was also included in the National Mine Action Plan 2010–2015 and integrated into the National Disability Strategy.

- A National Disability Council was established in Mozambique with the inclusion of the National Demining Institute as well as the Network for Mine Victims.[45]

In the 19 states with coordinating mechanisms, frequency of meetings was one indicator of activity levels and varied significantly by state. Victim assistance coordination in 12 states consisted of mostly regular meetings of the coordination body in 2009.[46] In Lebanon and Senegal the coordination body met as needed. In other states, such as Albania, the DRC, and Chad, informal meetings took place between the victim assistance mine action coordination body and key actors, such as international organizations, NGOs, and survivor organizations. In Thailand and Colombia the main victim assistance body met only once, but additional meetings were held by subcommittees. Victim assistance coordination bodies in Nicaragua and Yemen remained mostly inactive. In Lao PDR, Peru, and Thailand, coordination meetings were focused primarily on data collection and needs assessment.

In preparation for the Second Review Conference several states, including Angola, El Salvador, Sudan, and Thailand, used victim assistance meetings to prepare presentations on victim assistance progress and challenges.

Victim assistance focal points

At least 33 states had some sort of national victim assistance focal point. Twenty were mine action centers,[47] 11 were government ministries (usually social affairs or health, but also defense),[48] 11 were disability coordination bodies,[49] and one was a state hospital.[50] Little change in focal points was reported in 2009. Jordan designated a new focal point, as mentioned above, and the focal point (within the national mine action center) in Lebanon gained full responsibility for coordination of victim assistance. Government victim assistance focal points in Nicaragua, Serbia, and Zambia were inactive in 2009

Development of national plans

At least 14 states were identified as having victim assistance or broader disability plans used in a victim assistance framework.[51] Of these, three reported having adopted new multiyear plans in 2009:

- The National Plan of Action for Persons with Disabilities including Landmine/ERW Survivors 2009–2011 was adopted by Cambodia’s Prime Minister in August 2009 and sub-decrees were being formulated under the plan, including restructuring of the national Disability Action Council.

- Nepal’s Ministry of Peace and Reconstruction led the development of a five-year national strategic framework for victim assistance by the government and key national and international stakeholders.

- On 25 November 2009, Senegal approved the National Victim Assistance Plan 2010–2014. It was developed through the Ad Hoc Victim Assistance Committee, involving government ministries, service providers, and the Senegalese Association of Mine Victims and was based on data gathered through the October 2009 civilian survivor needs assessment. It included provisions to monitor the implementation of the plan that include key victim assistance stakeholders, including survivors and their representative organizations.

Despite the importance of monitoring progress in the implementation of victim assistance plans, El Salvador was the only state to report a specific monitoring mechanism through regular meetings of the Council for Integrated Attention for Persons with Disabilities sub-committee on victim assistance, which was also responsible for monitoring national implementation of the UNCRPD.

Survivor Inclusion

The Mine Ban Treaty requires States Parties to provide assistance for the care and rehabilitation, and social and economic reintegration, of mine victims. While not made explicit in the treaty, subsequent action plans have clarified that mine survivors, their families, and representative organizations should not just be recipients of assistance but active participants in all aspects of treaty implementation. However, monitoring this inclusion has been difficult, particularly at the national level—the level at which survivors have the greatest impact on victim assistance.[52]

At the Second Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty in December 2009, States Parties renewed the call for survivors to participate in treaty meetings as part of government delegations but also made it clear that survivors and their representative organizations should be meaningfully involved in all victim assistance activities. Action 29 of the Cartagena Action Plan says, “Ensure the continued involvement and effective contribution in all relevant convention related activities by health, rehabilitation, social services, education, employment, gender and disability rights experts, including mine survivors, inter alia by supporting the inclusion of such expertise in their delegations.”[53]

In 2009, at least seven States Parties—Australia, BiH, Colombia, Jordan, Peru, Tajikistan, and Thailand—included a mine/ERW survivor or other person with a disability in their delegations to the intersessional Standing Committee meetings or the Second Review Conference.

At the national level, in 2009, mine/ERW survivors, or their representative organizations, participated in victim assistance coordination and implementation in 23 states.[54] The quality of this participation varied, often in correlation with the effectiveness of the coordinating mechanism itself. In El Salvador some relevant disability organizations noted that they were not included in coordination meetings, though other organizations were. In other countries, such as China, India, and Mozambique, there were disability coordination mechanisms that included persons with disabilities and/or their representative organizations.[55]

In 29 states survivors were involved in the implementation of victim assistance;[56] in 22 there was no information available about their involvement; and in 11 states and areas, they were known not to be included.[57] Often this participation was through NGOs, survivor’s associations, or international organizations, such as the ICRC.[58] In states where survivors were included in the implementation of victim assistance, it was not necessarily systematic or widespread. For example, in Colombia peer support and survivor-led initiatives were exceptions rather than the norm, and in Peru, survivor involvement was mainly limited to advocacy activities.

Survivors were most often active in peer support, social inclusion, and advocacy on survivors’ rights, but in several states they also active in the fields of physical rehabilitation and economic inclusion.[59

Quality and Accessibility of Services

Although States Parties committed to provide a holistic set of services and respect the rights of mine/ERW survivors, by the end of 2009, they recognized that, by and large, most survivors had not experienced significant overall improvements in quality or access to a range of necessary services.[60] The Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 stressed the continued need to dedicate efforts to improving the quality of and access to services, by calling to “remov[e] physical, social, cultural, economic, political, and other barriers, including by expanding quality services in rural and remote areas and paying particular attention to vulnerable groups.”[61]

Quality

In 2009, an overall improvement in the quality of victim assistance services was reported in just four states: Eritrea, Lao PDR, Tajikistan, and Vietnam. However, in Lao PDR and Tajikistan, this improvement was only slight. In Pakistan and Palestine, the overall quality of services decreased, mainly due to continued armed violence and increasing numbers of war-injured people overwhelming existing services.

Accessibility

Access to services improved in 10 states and areas, while nine saw an overall decrease in accessibility.[62] In Abkhazia and Lao PDR, better accessibility was attributed to an increase in service providers and/or an expansion in the services offered. In Senegal, expanded mobile outreach services removed transport and security concerns for some survivors in need of services. In El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Vietnam, government efforts to decentralize services and/or increase funding for services for persons with disabilities promoted accessibility. Decreases in accessibility were most often related to ongoing armed conflict or a lack of security, such as in Pakistan. Decreased access was also seen in the most volatile regions of Afghanistan and Sudan. The departure of international organizations providing assistance decreased accessibility in Chad and Jordan,[63] and continued to adversely affect physical rehabilitation services in Angola.

International Legislation and Policies

As the Mine Ban Treaty lacked detail on what constituted victim assistance obligations for States Parties, the Nairobi Action Plan was the operational framework from 2005–2009. In this time period, progress was made mostly on coordination, but there was also a greater understanding of the numerous remaining challenges. Drawing lessons from the Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009, the Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 includes firmer and more comprehensive commitments for States Parties on issues such as survivor inclusion, coordination, progress reporting, and, most importantly, appropriate, qualitative, and accessible services based on assessed needs of survivors, in the geographic areas where they are most needed. The raised benchmark should provide a more solid basis to monitor the extent to which affected states and the international community address the real needs of survivors.

Other international mechanisms with relevance to victim assistance include the UNCRPD, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and Protocol V on ERW of the Convention on Conventional Weapons. The Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009 laid the ground work for the inclusion of principles of non-discrimination, the integration of survivors in the larger group of persons with disabilities, and the broad definition of “a victim” in these legal instruments. The enhanced legal framework and the development of common understandings were reflected in the Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 which calls for a holistic and integrated approach to victim assistance in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law

UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The UNCRPD is considered to “provide the States Parties with a more systematic, sustainable, gender sensitive and human rights based approach by bringing victim assistance into the broader context of persons with disabilities.”[64] Of the 56 states[65] profiled, over half (29) had ratified the UNCRPD by 1 August 2010 including 20 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty (10 of these ratified the UNCRPD in 2009 or 2010 through August).[66] Another nine states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty had ratified the UNCRPD by 1 August 2010; six did so in 2009 or in 2010 through August.[67] Another six Mine Ban Treaty States Parties and 10 states not party had signed but not yet ratified the convention as of 1 August 2010, including three who did so in 2009.[68]

In 2009, Mine Ban Treaty States Parties reported taking steps to implement the UNCRPD, which impacted mine/ERW survivors as well. For example in El Salvador, the victim assistance focal point was also the focal point for the implementation of the UNCRPD and monitored implementation of both instruments. In Nicaragua, a needs assessment of persons with disabilities initiated in October 2009 also included mine/ERW survivors. Thailand strongly connected its victim assistance coordination with its efforts to implement the UNCRPD.

Convention on Cluster Munitions

Influenced by the challenges experienced under the Mine Ban Treaty, the victim assistance provisions in the Convention on Cluster Munitions are more precise and comprehensive, making victim assistance a central component of the treaty’s humanitarian goals. The Convention on Cluster Munitions ensures the full realization of rights of all persons in communities affected by cluster munitions by obligating states to adequately provide assistance, without discriminating between people affected by cluster munitions and those who have suffered injuries or disabilities from other causes.

As of 10 September 2010, four profiled states with cluster munition victims[69] and four without known victims had ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[70] Another 17 had signed, but not yet ratified, the Convention on Cluster Munitions—including Lebanon, which has both mine and cluster munition victims but has not joined the Mine Ban Treaty—and 15 were Mine Ban Treaty States Parties.[71]

Protocol V of the Convention on Conventional Weapons

Protocol V on ERW of the Convention on Conventional Weapons addresses victim assistance in a similar manner to the Mine Ban Treaty. However in November 2008, the High Contracting Parties to Protocol V adopted a specific plan of action on victim assistance, which is more in line with the Mine Ban Treaty Action Plans as well as the Convention on Cluster Munitions, albeit of a less binding nature.[72] Protocol V, with its plan of action on victim assistance, creates the opportunity for synergies in victim assistance within states with ERW survivors as well as responsibilities for mine survivors.

[1] Figures include individuals killed or injured in incidents involving devices detonated by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person or a vehicle, such as all antipersonnel mines, antivehicle mines, abandoned explosive ordnance (AXO), UXO, and victim-activated IEDs. Not included in the totals are: estimates of casualties where exact numbers were not given; incidents caused or reasonably suspected to have been caused by remote-detonated mines or IEDs that were not victim-activated; and people killed or injured while manufacturing or emplacing devices. In many states and areas, numerous casualties go unrecorded and thus, the true casualty figure is likely significantly higher.

[2] The 58 states and six areas where casualties were identified in 2009 are: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, China, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, Cyprus, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Georgia, Guinea-Bissau, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, South Korea, Kuwait, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Senegal, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Vietnam, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe, as well as Abkhazia, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Palestine, Somaliland, and Western Sahara.

[3] For 2009, the Monitor actively collected victim assistance and casualty data for states with significant numbers of survivors (more than 1,000) and/or where there have been 10 or more casualties per year for the previous three reporting years. While passive monitoring of other states was maintained, the change in the Monitor’s methodology and coverage for 2010 makes it possible that a small number of casualties may have occurred in states no longer profiled, which have not been included in the totals above. However, these small numbers would not significantly affect the decreasing casualty trend, which is more related to decreased new use of mines and IEDs, a reduction in global armed violence since the 1990s, and more effective mine action programs.

[4] Recorded casualties gradually reduced throughout the decade from more than 8,000 per year between 1999 and 2003 to just over 7,000 in 2005, and fewer than 5,500 per year since 2007. The total casualty figure for 2008 was revised upward as updated information became available. Landmine Monitor Report 2009 reported a total of 5,197 casualties. Casualty data for 2008 was revised in nine countries, two of which were revised downward and seven increased. These changes are indicative of the fluctuating nature of casualty data as new information is gathered and also as some data collection mechanisms improve and others decline.

[5] No casualties were identified in 2009 in: Bangladesh, Cote d’Ivoire, Greece, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Poland, Rwanda, Serbia, and the United States. Morocco, Rwanda, Serbia, and the US were profiled by the Monitor in 2010; the remaining ten were not. Of those not profiled in 2010, it is almost certain that a limited number of ERW casualties occurred in Poland and some IED casualties occurred in Bangladesh. Passive monitoring of the other states not profiled did not reveal any casualties in 2009.

[6] The category of “civilian casualties” did not include humanitarian clearance personnel, who are also civilians but were, as in previous years, recorded in a separate category for deminers, to enable drawing more detailed research conclusions.

[7] The year 2008 marked the first reporting period that the Monitor had access to information on substantial numbers of government military casualties in Myanmar (508 casualties). In comparison, just three military casualties were identified in Myanmar for 2009 and nine for 2007. Data on government military casualties was not provided for 2009.

[8] States/area with casualties among deminers in 2009 are: Abkhazia, Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Croatia, Cyprus, Iraq, Lebanon, Mozambique, Russia (Chechnya), Tajikistan, Ukraine, and Yemen.

[9] In 2008, eight demining casualties were identified in Iran. No casualty data for deminers in Iran was available for 2009 but there was one report stating that mines and ERW continued to cause “countless” casualties among deminers. See the Country Profile for Iran, www.the-monitor.org/cp/ir.

[10] The gender of five deminers was unknown (three in Ukraine, one in Cyprus, and one in Angola).

[11] The gender of 909 casualties was unknown (23% of the total compared to 21% for 2008).

[12] The 7 states where the proportion of female casualties increased in 2009 are: Afghanistan, Chad, Georgia, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Pakistan, and Thailand. In the case of Guinea-Bissau, female casualties increased from none in 2008 to 10 in 2009, but all occurred in the same ERW incident.

[13] The 11 states/areas where children made up half or more of all civilian casualties in 2009 are: Afghanistan, Chad, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, India, Jordan, Mozambique, Nepal, Somalia, Somaliland, and Sudan.

[14] This includes all 674 casualties identified in Colombia. While these casualties are registered by the Presidential Program for Mine Action as having been caused by antipersonnel mines, it is widely accepted that these casualties are caused by both antipersonnel mines and victim-activated IEDs, which act as antipersonnel mines. These 674 Colombian casualties have been excluded from the total number of antipersonnel mine (and victim-activated IED) casualties, as in previous years. In 2008, for nearly 41% of casualties the device causing the incident was unknown, of these, casualties in Colombia made up 15%.

[15] The decline of 202 antipersonnel mine casualties from 2008 to 2009 is related to a significant decline in these casualties, from 210 to 29, in Afghanistan, mostly due to a change in the way data was collected.

[16] The decline of 166 antivehicle mine casualties from 2008 to 2009 is related to a significant decline in these casualties, from 136 to 20, in Afghanistan, mostly due to a change in the way data was collected.

[17] ERW including UXO and AXO, but excluding cluster munitions remnants.

[18] For more detailed information see the Country Profile for Afghanistan, www.the-monitor.org/cp/af.

[19] However, information on casualties in Afghanistan in 2008 included 128 casualties for which the device type was unknown and were possibly victim-activated IED casualties.

[20] While data collection practices in Colombia make it impossible to determine the exact number of antipersonnel mine casualties, there were known to have been some in the country in 2009. Sudan is the only state with casualties from unexploded submunitions but without casualties reported from other ERW, but the high number of casualties caused by unknown devices makes it likely that in Sudan there were also ERW casualties. While the specific number of victim-activated IED casualties in Colombia is not known, there were known to have been some.

[21] Based on information for 342 antipersonnel mine casualties. For 171 of the total 513 antipersonnel mine casualties (33%) the age was unknown.

[22] These figures again exclude data from Colombia.

[23] The gender was known for 871 casualties due to other ERW.

[24]See UN, “Review of the Operation and Status of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Antipersonnel Mines and on Their Destruction: 2005–2009,” Cartagena, 30 November–4 December 2009, APLC/CONF/2009/WP.2, 18 December 2009, (hereafter referred to as “Cartagena Review Document”); and Voices from the Ground: Landmine and Explosive Remnants of War Survivors Out on Victim Assistance (Brussels: Handicap International, 2 September 2009).

[25] The 56 profiled countries are: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, China, Colombia, Croatia, DRC, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Georgia, Guinea-Bissau, India, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Rwanda, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, the UK, US, Vietnam, Yemen, and Zambia. Of these, 33 were States Parties and 23 were states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty.

[26] The other areas not recognized as states by the UN are: Abkhazia, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Palestine, Somaliland, and Western Sahara.

[27] Each of the 62 countries and areas profiled had at least 1,000 mine/ERW survivors on their territory by the end of 2009 and/or had had 10 or more casualties per year, consistently, for the previous three reporting years (2006–2008). These included the 26 countries that self-identified as having significant numbers of mine survivors, and the greatest responsibility to act, but also the greatest needs and expectations for assistance in providing adequate services for the care, rehabilitation, and reintegration of survivors in the 2005–2009 period. The 26 self-identifying countries are: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, DRC, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uganda, and Yemen.

[28] In 2010, the Monitor aimed to systematically establish a baseline for survivor inclusion at the national level so that progress in this area, called for by survivors themselves, and in new norms, can be measured.

[29] UN, “Cartagena Review Document,” Cartagena, 30 November–4 December 2009, APLC/CONF/2009/WP.2, 18 December 2009, p. 44.

[30] Ibid. The report did not specify which these four states were.

[31] For information about needs assessments and survivor surveys carried out prior to 2009, please see previous editions of Landmine Monitor.

[32] States Parties: Algeria, BiH, Jordan, Peru, and Thailand. States not party: Lao PDR and Lebanon.

[33] States Parties: Iraq, Mozambique, Senegal, Sudan, and Uganda. States not party: Iran and Sri Lanka. The Sudan Landmine Impact Survey (LIS), completed in 2009, collected recent casualty data in the 16 most mine/ERW affected states and surveyed survivors in those same states as to whether or not they had received emergency medical care, physical rehabilitation, and/or vocational training.

[34] Iran, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mozambique, Senegal, and Uganda.

[35] Iraq, Peru, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

[36] In the case of Jordan, the survey was completed in March 2010 and, by the time of the publication it was not yet known how the data was being used. Information was also not available regarding the use of LIS data on survivors’ needs in Sudan. No information was available on Algeria.

[37] Such data collection occurred in Abkhazia, Afghanistan, Albania, Nepal, and Yemen, but this list cannot be considered exhaustive as Monitor research did not explicitly request information about efforts by service providers to collect data on survivors’ needs.

[38] “Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014: Ending the Suffering Caused by Anti-Personnel Mines,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 25, (hereafter referred to as the “Cartagena Action Plan”).

[39] “Cartagena Action Plan,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 25.

[40] UN, “Cartagena Review Document,” Cartagena, 30 November–4 December 2009, APLC/CONF/2009/WP.2, 18 December 2009, p. 40.

[41] “Cartagena Action Plan,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 24.

[42] States Parties: Albania, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Jordan, Nicaragua, Peru, Senegal, Uganda, and Yemen. States not parties: Georgia, Lao PDR, and Lebanon.

[43] Other countries which included victim assistance in mine action coordination, but did not have a distinct victim assistance coordination mechanism in 2009 included State Party Croatia and states not parties Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

[44] Approval for the NDCC was granted in August 2009 but the first official meeting of the committee was not held until the first quarter of 2010.

[45] The National Disability Council was not yet operational at the end of 2009.

[46] Nine States Parties: Afghanistan, BiH, El Salvador, Eritrea, Iraq, Jordan, Nepal, Sudan, and Tajikistan. Three states not parties: Lao PDR, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

[47] States Party: Albania, Angola, BiH, Burundi, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Mozambique, Peru, Senegal, Sudan (northern), Tajikistan, Thailand, and Yemen. States not parties: Azerbaijan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Libya.

[48] States Parties: Afghanistan, Algeria, Cambodia, DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Nicaragua, Sudan (southern), and Uganda. States not party: Georgia, US.

[49] States Parties: Afghanistan, Cambodia, El Salvador, and Jordan. In the cases of Afghanistan and Cambodia, the victim assistance focal point was based within a ministry that coordinated disability issues.

[50] State Party: Serbia.

[51] States Parties: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Uganda. States not parties: Azerbaijan, Nepal, and the US.

[52] Action 38 of the Nairobi Action Plan calls on States Parties to “Ensure effective integration of mine victims in the work of the Convention, inter alia, by encouraging States Parties and organizations to include victims on their delegations.” Nairobi Action Plan, “Final Report of the First Review Conference,” 29 November–3 December 2004, APLC/CONF/2004/5, 9 February 2005, Action 38.

[53] “Cartagena Action Plan,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 29.

[54] States Parties: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Jordan, Peru, Philippines, Senegal, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Uganda. States not parties: Azerbaijan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Syria, the US, and Vietnam.

[55] In Mozambique, there was some coordination of victim assistance related to the pilot survivor needs assessment in Maputo province which involved survivors. In China and India there were no coordination mechanisms specific to mine/ERW victim assistance.

[56] States Parties: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, DRC, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Nepal, Nicaragua, Peru, Senegal, Sudan, Tajikistan, Uganda, the UK, and Yemen. States not parties: Azerbaijan, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Syria, US, and Vietnam.

[57] States Parties: Burundi, Guinea-Bissau, Serbia, Thailand, and Turkey. States not parties and areas: China, Georgia, India, Iran, and Russia, as well as Kosovo.

[58] Most information on survivor inclusion in the implementation of services was provided by NGOs, not governments.

[59] Some examples of countries where survivors were involved in providing physical rehabilitation include: Afghanistan, DRC, El Salvador, Georgia, and Nicaragua; and in economic inclusion activities include: BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, and Senegal.

[60]See, UN “Cartagena Review Document,” Cartagena, 30 November–4 December 2009, APLC/CONF/2009/WP.2, 18 December 2009, pp.41–43; and Voices from the Ground: Landmine and Explosive Remnants of War Survivors Out on Victim Assistance (Brussels: Handicap International, 2 September 2009).

[61] UN, “Cartagena Action Plan,” Cartagena, 11 December 2009, Action 31.

[62] States and areas with increased accessibility included: Abkhazia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Iraq, Lao PDR, Myanmar (just within physical rehabilitation), Nicaragua, Senegal, the US, and Vietnam. States and areas with decreased accessibility included: Afghanistan, Angola, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, and Pakistan, as well as Palestine.

[63] In Jordan, the closure of Survivor Corps, an international NGO providing peer support and other services, was seen to have an impact on access to overall services since it had served as an important information source to refer survivors to other service providers.

[64] UN, “Cartagena Review Document,” Cartagena, 30 November–4 December 2009, APLC/CONF/2009/WP.2, 18 December 2009, pp. 54–55.

[65] Of the 62 states and areas profiled, six areas are not recognized by the UN and cannot join international conventions, therefore they have not been included in this count.

[66] The 20 Mine Ban Treaty States Parties that have ratified the UNCRPD are: Algeria (2009), BiH (2010), Croatia (2007), El Salvador (2007), Ethiopia (2010), Jordan (2008), Nicaragua (2007), Niger (2008), Peru (2008), Philippines (2008), Rwanda (2008), Serbia (2009), Sudan (2009), Thailand (2008), Turkey (2009), Uganda (2008), Ukraine (2010), the UK (2009), Yemen (2009), and Zambia (2010).

[67] The nine states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty that have ratified the UNCRPD are: Azerbaijan (2009), China (2008), Egypt (2008), India (2007), Iran (2009), Lao PDR (2009), Morocco (2009), Nepal (2010), and Syria (2009).

[68] The six Mine Ban Treaty States Parties that have signed the UNCRPD are: Albania (2009), Burundi (2007), Cambodia (2007), Colombia (2007), Mozambique (2007), and Senegal (2007). States not parties: Armenia (2007), Georgia (2009), Israel (2007), Lebanon (2007), Libya (2008), Pakistan (2008), Russia (2008), Sri Lanka (2007), the US (2009), and Vietnam (2007).

[69] Mine Ban Treaty States Parties: Albania, BiH, and Croatia. State not party: Lao PDR.

[70] Mine Ban Treaty States Parties: Nicaragua, Burundi, Niger, and Zambia.

[71] Afghanistan, Angola, Chad, Colombia, DRC, El Salvador, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Mozambique, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Senegal, Uganda, and the UK.

[72] The Monitor has victim assistance profiles on 10 High Contracting Parties to Protocol V that are also Mine Ban Treaty States Parties: Albania, Belarus, BiH, Croatia, El Salvador, Guinea-Bissau, Nicaragua, Peru, Tajikistan, and Ukraine. Five High Contracting Parties that are not Mine Ban Treaty States Parties are also profiled: Georgia, India, Pakistan, Russia, and the US. Georgia, Pakistan, and Russia reported on victim assistance in their Protocol V national annual reports for 2009; Ukraine reported on casualties.