Cluster Munition Monitor 2018

Contamination and Clearance

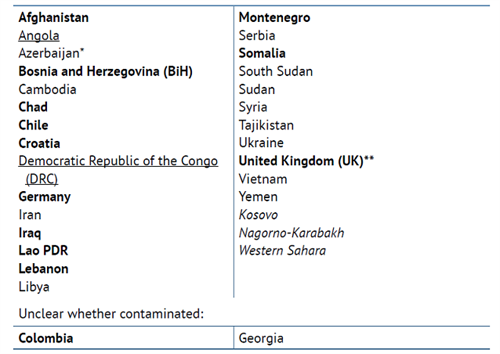

States and other areas with cluster munition contamination as of August 2018

* Contamination exists in areas outside of government control. There may be minimal contamination in areas under government control.

** Non-signatory Argentina and State Party UK both claim sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Malvinas, where any cluster munition contamination is likely within mined areas.

Note: States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions are indicated in bold; signatories are underlined; other areas are in italics.

Summary[1]

As of 1 August 2018, a total of 26 states and three other areas are contaminated by cluster munition remnants.[2] This includes 12 States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, two signatories, and 12 non-signatories. It is unclear whether one State Party and one non-signatory are contaminated.[3]

No country completed clearance in 2017.

In 2017, little progress was made in improving the understanding of the extent of the problem globally. For more than half of the countries, the full scale of contamination is not known. Survey efforts in a number of states and other areas, including the four most heavily contaminated, are slowly increasing the knowledge about locations of contaminated areas. However, many states do not know the extent of contamination on their territory. In 2017, even in states and other areas with a good understanding of the problem, clearance operators continued to identify previously unknown contaminated areas.

New use increased contamination in Syria and Yemen in 2017. There were allegations of new use in Libya and Egypt in 2017.

In 2017, at least 93km2 of contaminated land was cleared, with a total of at least 153,000 submunitions destroyed during land release (survey and clearance) operations.[4] However, this estimate is based on incomplete data. It represents an 6% increase on the land cleared and 9% increase on the number of submunitions destroyed in 2016. Between 2010 and 2017, a total of more than 688,000 submunitions were destroyed and at least 518km2 of land was cleared worldwide. In 2017, more than three-quarters (78%) of reported global clearance took place in Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Vietnam—three of the world’s most contaminated states. A decrease in recorded cluster munition-contaminated areas, however, was reported in only a handful of countries, in part because the full extent of contamination is still not known in many countries.

Only one State Party, Croatia, appears on track to meet its Article 4 clearance deadline. Four States Parties are not on track, and it is unclear whether the remaining States Parties will meet their deadlines.

Germany commenced clearance of cluster munitions for the first time in 2017, having started preparing the land for clearance in 2016.

Conflict and insecurity in 2017 and 2018 impeded land release efforts in three States Parties (Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia), six non-signatories (Libya, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen), and signatory Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Contamination and Land Release

Contamination statistics

The full extent of contamination remains unknown in the most heavily contaminated countries in the world: Cambodia, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Vietnam. Survey efforts continued to improve the understanding of the problem in these countries. Nonetheless, in these and many other countries, the reported size of contamination did not decrease because either the extent of contamination is unknown, no clearance took place, or previously unknown contaminated areas were identified.

In only four countries and one other area did the total reported size of cluster munition-contaminated areas decrease during 2017 as a result of land release (survey and clearance) efforts: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, and South Sudan, along with Western Sahara. However, in South Sudan and Western Sahara is it thought that undiscovered areas of contamination exist.

Previously unknown or unreported contaminated areas were recorded in 2017 in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Croatia, DRC, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Libya, South Sudan, Ukraine, and Vietnam, along with other areas Nagorno-Karabakh and Western Sahara. In Syria and Yemen, although unexploded submunitions were found and destroyed, no specific locations were recorded as hazardous areas in data management systems.

New use was reported in 2017 in Syria and Yemen.[5] The extent of existing and new contamination in these countries is not known as insecurity prevents or hampers survey and clearance.

The data contained in the following table is drawn from various sources. Those that appear to be most accurate and complete have been used.[6]

Estimated cluster munition contamination at the end of 2017

|

Country/ Other Area |

Contamination (km2) |

|

|

End 2017 |

Comments |

|

|

More than 1,000km2 (massive) |

||

|

Lao PDR |

Not known |

Survey efforts are underway to define the problem. Around 500km2 has been identified |

|

Vietnam |

Not known |

Survey efforts are underway to define the problem |

|

100–1000km2 (heavy) |

||

|

Cambodia |

Not known |

Survey efforts are underway to define the problem. Recorded contamination is at least 624km2. However, some operators question the accuracy of this data |

|

Iraq |

Not known, at least 165 |

131.07km2 confirmed hazardous area (CHA) and 33.47km2 suspected hazardous area (SHA) identified. Survey continues to identify areas of contamination |

|

5–99km2 (medium) |

||

|

Afghanistan |

6.52 |

There may be more contamination, as operators continue to encounter scattered submunitions |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

6.47 |

The difference in total contamination between the end of 2016 and 2017 cannot be reconciled by the land release data |

|

Chile |

97 |

No survey has been conducted to date. This is the size of the four military training areas reported to be contaminated. Actual contaminated area may be smaller |

|

Germany |

11 |

Size of a former military area that contains cluster munition contamination |

|

Lebanon |

24 |

17.2km2 CHA and 6.8km2 SHA. Previously unknown contamination continued to be identified resulting in an increase in known contamination despite clearance efforts |

|

South Sudan |

Not known, at least 4.5 |

2.76km2 CHA and 1.78km2 SHA. The true scale of contamination is not known as some areas cannot be accessed |

|

Syria |

Not known |

Extensive use of cluster munitions since 2012, but the extent of contamination is not known as no survey has been conducted |

|

Ukraine |

Not known |

Not contaminated by cluster munition remnants prior to the conflict that started mid-2014. No comprehensive survey has been conducted |

|

Yemen |

Not known, at least 18.6 |

Contamination has been identified in at least seven governorates, primarily from new use since April 2015, but the only recorded contamination is in the northern Saada governorate, predating the current conflict |

|

Kosovo |

15.4 |

Slight increase from the 15km2 reported at the end of 2016 |

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

71.62* |

A small increase from 2016, despite clearance in 2017, following confirmation of SHAs |

|

Less than 5km2 (light) |

||

|

Croatia |

1.05 |

A decrease on the 1.74km2 at the end of 2016 due to clearance. However, areas of previously unknown contamination were discovered in four counties |

|

Montenegro |

1.72 |

The same size of contamination was reported at the end of 2013, as a result of survey. No clearance was conducted in 2016 or 2017 |

|

Serbia |

2.54 |

0.64km2 CHA and 1.9km2 SHA. This represents a decrease from 2016 |

|

Western Sahara |

2.6 |

Although more contamination was identified in 2017, overall reported contamination decreased as a result of clearance |

|

Extent of contamination not known (light or medium) |

||

|

Angola |

Not known |

There may remain abandoned cluster munitions or unexploded submunitions. The last recorded finding was in 2016. As of May 2018, plans to conduct limited battle area clearance in the area had not been implemented |

|

Azerbaijan |

Not known |

There are significant quantities of cluster munition remnants in and around Nagorno-Karabakh, in areas not under government control (see Nagorno-Karabakh). There may also be some minimal contamination in the territory under Azerbaijan government control |

|

Chad |

Not known |

No comprehensive survey has been conducted. The most recent discovery of cluster munition remnants was in 2015 |

|

Democratic Republic of the Congo |

Not known |

Clearance of all known contamination was completed in 2017. However, subsequently more submunitions were discovered in South Kivu |

|

Iran |

Not known |

Some contamination is believed to remain from the Iran-Iraq war, but no survey has been conducted |

|

Libya |

Not known |

50,400m2 was confirmed as contaminated in 2017 |

|

Somalia |

Not known |

No comprehensive survey has been conducted. The most recent discovery of cluster munition remnants was in 2016 |

|

Sudan |

Not known |

2km2 approx. is recorded, but insecurity prevents survey of other areas that might be contaminated. In 2018, Sudan provided details for the first time of the land release of seven contamination areas that were reported in 2011–2013 |

|

Tajikistan |

At least 0.14km2 |

0.14km2 discovered through survey in 2018. An additional 0.87km2 of battle area may contain cluster munition remnants. |

|

United Kingdom |

Not known |

Any cluster munition contamination on the Falkland Islands/Malvinas is most likely within the mined areas, all of which are recorded |

|

Unclear whether contaminated |

||

|

Colombia |

Unclear |

If contaminated, then minimal |

|

Georgia |

Unclear |

Not contaminated, with the possible exception of South Ossetia |

* The amount of cluster munition contamination at the end of 2016 was revised to 71.5km2 as the figure reported in the 2017 profile did not include clearance of suspended areas.

Notes: States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions are indicated in bold; signatories are underlined; other areas are in italics.

Land release statistics

In 2017, the overwhelming majority of reported clearance took place in three of the most contaminated states, Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Vietnam where 78% of the global cluster munition-contaminated land clearance and 86% of unexploded submunition destruction took place.

Germany reported clearance of cluster munition remnants for the first time. Clearance was also reported in Afghanistan, BiH, Croatia, DRC, Iraq, Lebanon, Serbia, South Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Yemen, and other areas Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara.[7]

However, no cluster munition survey or clearance was reported in Angola, Chad, Chile, Colombia, Iran, Montenegro, Somalia, Sudan, or the UK. In Azerbaijan, there were no reports of cluster munition survey or clearance in areas under government control. Although cluster munition-contaminated areas were recorded in Libya and Ukraine in 2017, no clearance was reported.

The information provided in the table below draws on data provided in Article 7 transparency reports, by national programs, and by mine action operators. There are sometimes discrepancies between these sources. Where this is the case, the data that appears to be most reliable is used and a note has been made. For an explanation of land release terminology, see “Improving clearance efficiency: land release,”in Cluster Munition Monitor 2015.

Cluster munition land release in States Parties, 2010–2017

|

Country/ Other Area |

Land release through clearance |

Survey in 2017 |

Notes, including on change since 2016 |

|||

|

2010–2017 total |

2017 |

|||||

|

km2 |

Number of submunitions destroyed |

km2 |

Number of submunitions destroyed |

|||

|

Afghanistan |

6.1 |

6,704 est. |

2.83 |

383 |

One CHA 1.86km2 added to database |

Clearance of recorded contaminated area resumed in 2017. Discrepancies between data sources |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

1.35 |

3,499 |

0.27 |

1,246 |

0.6km2 reduced through technical survey |

Land release results do not account for the change in the reported extent of contamination during 2017

|

|

Chad |

N/R |

N/R |

0 |

0 |

None |

No change |

|

Chile |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

None |

No change |

|

Colombia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

No efforts yet made to confirm that there is no remaining contamination |

|

Croatia |

5.85 est. |

1,779 |

1.0 |

123 |

0.16km2 confirmed

|

A slight decrease from 2016 clearance results |

|

Germany |

0.5 |

527 |

0.5 |

513 |

Clearance commenced in 2017 |

|

|

Iraq |

Unclear |

Unclear |

At least 4.7 |

At least 1,188 |

22.45km2 CHAs confirmed

|

Major discrepancies between data sources and absence of data from some operators |

|

Lao PDR |

368.14 est. |

535,481 |

33 |

117,974 |

200km2 confirmed as CHA |

Increase from 2016 clearance results. Discrepancies between data sources |

|

Lebanon |

18.22 est. |

28,710 est. |

1.4 |

5,525 |

0.52km2 identified through NTS and rapid response callouts |

Discrepancies between data sources |

|

Montenegro |

0.0065 |

7 est. |

0 |

0 |

None |

Funding secured to commence clearance in 2018 |

|

Somalia |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

None |

No change |

|

United Kingdom |

0 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

None |

In June 2017, an empty BL755 cluster munition container was discovered |

Note: NTS = non-technical survey; TS = technical survey; SHA = suspected hazardous area; CHA = confirmed hazardous area.

Cluster munition land release in signatories, 2010–2017

|

Country/ Other Area |

Land release through clearance |

Survey in 2017 |

Notes, including on change since 2016 |

|||

|

2010–2017 total |

2017 |

|||||

|

km2 |

Number of submunitions destroyed |

km2 |

Number of submunitions destroyed |

|||

|

Angola |

0 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

No change |

|

|

Democratic Republic of the Congo |

0.19 |

521 est. |

3,900m2 cleared |

242 |

One area of unrecorded size cancelled |

By May 2017, the last known contamination was cleared, but additional contamination was since discovered, which was undergoing TS as of June 2018 |

Note: NTS = non-technical survey; TS = technical survey; SHA = suspected hazardous area; CHA = confirmed hazardous area.

Cluster munition land release in non-signatories, 2010–2017

|

Country/ Other Area |

Land release through clearance |

Survey in 2017 |

Notes, including on change since 2016 |

|||

|

2010–2017 total |

2017 |

|||||

|

km2 |

Number of submunitions destroyed |

km2 |

Number of submunitions destroyed |

|||

|

Azerbaijan |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

None |

See Nagorno-Karabakh |

|

Cambodia |

Unclear |

29,575 at least |

23.5 |

8,367 |

2.7 km2 released through survey. 4.89km2 reported as confirmed. The reported estimate of contamination in eastern provinces increased by 93km2 between May 2017 and May 2018

|

Major discrepancies between data sources |

|

Georgia |

1.3 at least |

72 at least |

0 |

3 |

0.8km2 reduced |

|

|

Iran |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

No reports of survey or clearance operations |

|

Libya |

N/R |

460 at least |

N/R |

N/R |

50,400m2 confirmed as contaminated

|

An unreported number of submunitions were destroyed during explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) spot tasks |

|

Serbia |

6.77 |

1,497 |

0.18 |

76 |

None |

Decrease from 2016 clearance results |

|

South Sudan |

10.2 at least |

5,163 |

1 |

629 |

0.71km2 confirmed 0.06km2 cancelled through NTS |

Major decrease from 2016 clearance results |

|

Sudan |

0.02 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

None |

In 2018, for the first time Sudan reported on clearance that occurred between 2011–2013 |

|

Syria |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

6,633 |

None |

Clearance is taking place but results are not systematically recorded |

|

Tajikistan |

0.45 at least |

250 at least |

0.25 |

164 |

0.02km2 reduced through TS and 0.11km2 cancelled through NTS |

0.14km2 of additional contamination identified through survey in 2018 |

|

Ukraine |

Unclear |

Unclear |

N/R |

N/R |

0.43km2 confirmed |

Mine action activities are not systematically recorded, and it is not known how much land was cleared |

|

Vietnam |

Unclear |

42,129 at least |

16.75 |

6,157 at least |

54.71km2 confirmed |

Only international operators’ data is available. Most clearance is conducted by Army Engineering Corps, for which no data is available |

|

Yemen |

N/R |

6321 est. |

N/R |

3,245 |

N/R |

|

Note: NTS = non-technical survey; TS = technical survey; SHA = suspected hazardous area; CHA = confirmed hazardous area; N/R = not reported.

Cluster munition land release in other areas, 2010–2017

|

Country/ Other Area |

Land release through clearance |

Survey in 2017 |

Notes, including on change since 2016 |

|||

|

2010–2017 total |

2017 |

|||||

|

km2 |

Number of submunitions destroyed |

km2 |

Number of submunitions destroyed |

|||

|

Kosovo |

Up to 5.02 |

1,118 est. |

0.9 |

76 |

0.5km2 reduced, 2,290m2 cancelled |

Double the clearance conducted in 2016 |

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

41.04 at least |

2,449 |

1.1 |

52 |

1.5km2 confirmed, 0.26km2 reduced

|

Decrease from 2016 clearance results |

|

Western Sahara |

15.79 |

14,140 |

6.1 |

688 |

1.45km2 confirmed

|

Major increase from 2016 clearance results |

Note: NTS = non-technical survey; TS = technical survey; SHA = suspected hazardous area; CHA = confirmed hazardous area.

Clearance obligations under Article 4

Under the Convention on Cluster Munitions, each State Party is obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under its jurisdiction or control as soon as possible but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention. If unable to complete clearance in time, the State Party may request deadline extensions for periods of up to five years. No such requests have yet been made as the first clearance deadlines are 1 August 2020.

In seeking to fulfill their clearance and destruction obligations, affected States Parties are required to:

- Survey, assess, and record the threat, making every effort to identify all contaminated areas under their jurisdiction or control;

- Assess and prioritize needs for marking, protection of civilians, clearance, and destruction;

- Take “all feasible steps” to perimeter-mark, monitor, and fence affected areas;

- Conduct risk education to ensure awareness among civilians living in or around areas contaminated by cluster munitions;

- Take steps to mobilize the necessary resources at national and international levels; and

- Develop a national plan, building upon existing structures, experiences, and methodologies.[8]

The following table provides an assessment of progress of States Parties against clearance deadlines based on size of contamination, the existence of a resourced plan, progress to date, and obstacles to land release operations such as conflict and insecurity.

Clearance progress under the Convention on Cluster Munitions

|

Country |

Article 4 clearance deadline |

On track to meet deadline |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2022 |

Unclear |

|

BiH |

1 March 2021 |

Unclear |

|

Chad |

1 September 2023 |

Unclear |

|

Chile |

1 June 2021 |

Not on track |

|

Colombia |

1 March 2026 |

Unclear |

|

Croatia |

1 August 2020 |

On track |

|

Germany |

1 August 2020 |

Unclear |

|

Lao PDR |

1 August 2020 |

Not on track |

|

Iraq |

1 November 2023 |

Not on track |

|

Lebanon |

1 May 2021 |

Not on track |

|

Montenegro |

1 August 2020 |

Unclear |

|

Somalia |

1 March 2026 |

Too soon to determine likelihood of meeting deadline |

|

UK |

1 November 2020 |

Unclear |

Clearance completed

Eight States Parties have completed the clearance of their cluster munition-contaminated areas under the Convention on Cluster Munitions. None completed in 2017.

The eight States Parties that have in previous years completed the clearance of areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants are: Albania, the Republic of the Congo, Grenada, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Mozambique, Norway, and Zambia. One signatory, Uganda, and one non-signatory, Thailand, also completed clearance of areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants in previous years.

Progress by States Parties under the Dubrovnik Action Plan

The Dubrovnik Action Plan was adopted by States Parties at the Convention on Cluster Munitions First Review Conference in Dubrovnik, Croatia, in September 2015. It seeks to ensure the effective implementation of the provisions of the convention until the Second Review Conference in 2020. Section III (Actions 3.1–3.8) is related to clearance and risk reduction education.

This section examines the progress of States Parties against their Dubrovnik Action Plan commitments on the clearance and destruction of cluster munition remnants.[9]

Action 3.1—Assess the extent of the problem of cluster munition contamination

States Parties are required to provide an assessment of the extent of the problem of cluster munition contamination within two years of the First Review Conference or two years after entry into force of the convention for each State Party (refer to the table “Estimated cluster munition contamination” above for existing knowledge of extent of the problem.) By the end of 2017:

- Two states had a very good understanding of the extent of the problem.

- Six states had a fairly good understanding of the extent of the problem.

- Four states—including the two most heavily contaminated—had a poor understanding of the problem.

- One state may be able to declare it has no contaminated areas, once assessment and survey have been conducted.

The two States Parties that have a very good understanding of the problem are Croatia and Germany. In Croatia, all known contamination is contained within confirmed hazardous areas, except for a small amount of previously unknown contamination that was identified in four areas in 2017.[10] In Germany, all contamination is contained in 11km2 of a former military training area.[11]

The six States Parties that have a fairly good understanding of the extent of the problem are Afghanistan, BiH, Chile, Lebanon, Montenegro, and the UK. In two states, Afghanistan and Lebanon, many of the cluster munition-contaminated areas are known, but in 2017 previously unknown contamination continued to be discovered.[12] BiH is able to report a contamination figure, but this figure does not appear to be consistent with the amount of land released in 2017, and does not distinguish suspected hazardous areas from confirmed hazardous areas. Montenegro knows the locations of its contamination, but has two suspected areas that have yet to be surveyed.[13] Two states, Chile and the UK, know the locations of all contaminated areas, but the extent of contamination within those areas is not known. The UK has affirmed that, on the Falkland Islands/Malvinas, no areas known to be contaminated with cluster munition remnants exist outside areas already suspected of being contaminated with landmines or ERW.[14] Chile has not reported conducting any survey of the four military training areas that it suspects are contaminated.

The four States Parties that have a poor understanding of the extent or location of the cluster munition problem are Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Somalia. Lao PDR is the world’s most contaminated country, and the extent of affected areas is not known. It has now taken steps to improve its understanding, as in 2016 it committed to a nationwide non-technical and technical survey with a view to producing Lao PDR’s first baseline estimate of cluster munition contamination by the end of 2021.[15] As of May 2018, Lao PDR had confirmed around 500km2 of cluster munition contamination.[16] Iraq reported a significantly lower amount of CHA in 2017 than in 2016.[17] However, this did not match land release results, suggesting that the data does not provide a clear picture. Moreover, the priority of addressing mine-contaminated areas has slowed the survey efforts needed to determine the full extent of cluster munition contamination.[18] Although Chad and Somalia are probably contaminated by cluster munitions, survey is needed to identify suspected or confirmed hazardous areas.

Colombia may be able to declare it has no contaminated areas, once assessment and survey have been conducted.

Action 3.2—Protect people from harm

In accordance with their Article 4 obligations, through their Article 7 transparency reports, seven States Parties reported on measures to provide risk education and/or to prevent civilian access to areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants through marking and fencing in 2017: Afghanistan, BiH, Croatia, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon.[19]

In Germany and the UK, in particular, all known cluster munition contamination is completely fenced and marked. In Germany, the areas are completely perimeter-marked with warning signs and an official directive constrains access to the area.[20] The UK has conducted comprehensive perimeter-marking of mined areas potentially containing cluster munition remnants.[21]

In most affected States Parties, a humanitarian and/or socio-economic impact of contamination is reported to varying degrees, indicating the need for greater efforts to fulfill this action. In several states, cluster munition remnants continue to cause casualties (see the Casualties chapter for further details).

Action 3.3—Develop a resourced plan

States Parties are required to have a plan in place within one year of the First Review Conference or by entry into force of the convention for each State Party. Although only one State Party is on track to meet its deadline, a number of States Parties have improved their plans or obtained further resources in 2017.

Croatia states in its national mine action plan for 2018 that it aims to eliminate all known cluster munition-contaminated areas by the end of 2018, well ahead of its Article 5 deadline.[22]

Afghanistan has a funded project for clearance of cluster munitions, which is included in its Mine Ban Treaty workplan. However, contaminated areas identified after the plan was developed are not included in the project.[23]

In mid-2018, Montenegro secured funding to conduct survey and clearance in order to complete its Article 4 obligations.[24]

BiH developed a draft National Mine Action Strategy for 2018–2025, which is said to contain a plan and timeframe for completion of cluster munition clearance. It is awaiting parliamentary approval.[25]

Lao PDR plans to complete a survey by the end of 2021, which should provide the basis upon which a clearance plan can be developed.[26] However, this will not be achieved within the Article 4 clearance deadline, and an extension request will need to be submitted.

Lebanon’s 2011–2020 mine action strategic plan originally aimed to complete clearance of cluster munition remnants by 2016, but that was not achieved. Its second mid-term review revised the objective to 2020.[27]

Germany has not yet set specific milestones for the release of areas confirmed or suspected to contain cluster munition remnants.[28] Germany reported that it intends to meet its Article 4 deadline, but that some factors could lead to delays.[29]

Four States Parties do not have a cluster munition clearance strategy in place. They have not indicated an intention to develop such a plan, nor whether they expect to meet their Article 4 deadlines: Chad, Chile, Iraq, and the UK. Chad’s mine action plan notes that it adhered to the Convention on Cluster Munitions but does not detail plans to survey and clear cluster munition contamination.[30] Chile has not presented a plan for how it will achieve its Article 4 clearance deadline, and as of mid-2018, survey and clearance had not commenced. Iraq does not have a strategic plan for the clearance of cluster munition remnants, and the national priority has been given to tackling densely mine-contaminated areas liberated from the non-state armed group Islamic State (IS) to permit the return of displaced populations.[31] As any cluster munition contamination in the Falkland Islands/Malvinas is contained within existing minefields, the UK’s plan to clear all except 0.16km2 of the minefields by the end of March 2020 gives some indication of progress.[32] However, the UK has not stated whether it suspects there may be cluster munition remnants in the remaining areas.

Colombia reported in 2017 that it is in the process of establishing the location and extent of any contamination, but it did not provide details of any plan or activities in 2017 or 2018.[33] Once the necessary assessment and survey have been conducted, Colombia may be able to declare full completion of its Article 4 obligations. As of mid-2018, Somalia’s draft National Mine Action Strategic Plan for 2017–2020 was under review.[34] However, the draft did not contain specific provisions on addressing contamination from cluster munition remnants or compliance with Article 4 obligations.[35]

Action 3.5—Manage information for analysis, decision-making, and reporting

Each State Party is required to “record and provide information to the extent possible on the scope, extent and nature of all cluster munition-contaminated areas under its jurisdiction or control.” (For details of the extent to which states have a knowledge of the contaminated areas under their jurisdiction, see Action 3.1 above.)

The quality of reporting on survey and clearance is variable, and has not improved significantly overall in 2017. As in 2016, of those States Parties that conducted survey and clearance of cluster munition-contaminated areas in 2017, only Croatia, Germany, and the UK had clear, consistent land-release data across the different sources.

Discrepancies between survey and clearance data provided by mine action centers, operators, and Article 7 reports were found in Afghanistan, BiH, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon. This made it difficult to track progress toward completion of land release. These are the same states that had discrepancies within their data in 2016, indicating little improvement in information management.

In 2017, Chile submitted its first Article 7 report since 2013. However, as of 1 August 2018, it had not submitted its Article 7 report for 2017. As of 1 August 2018, Somalia had still not submitted its initial Article 7 report, which was due on 31 August 2016.

Action 3.7—Apply practice development[36]

States Parties continue to implement land release methodologies to improve the efficiency of clearance of cluster munition remnants. (For further information about land release, see “Improving clearance efficiency: land release” in Cluster Munition Monitor 2015.)

All the states that conducted land release of cluster munition-contaminated areas reported the use of technical and/or non-technical survey to confirm, reduce, or cancel hazardous areas: Afghanistan, BiH, Croatia, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon.[37]

Action 3.8—Promote and expand cooperation

International cooperation and assistance to support national capacity-building in program management is provided to almost all States Parties. It covers strategic planning and standards development, as well as the implementation of land release operations.

The UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) provides support to mine action programs in States Parties Afghanistan, Colombia, Iraq, and Somalia.[38] In Lebanon, it supports the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). In 2017, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) supported capacity development in Lao PDR[39] and Lebanon; and in collaboration with the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), it provided support to strategic planning in BiH.[40] In Colombia, the Organization of American States (OAS) serves as the monitoring body for humanitarian demining in Colombia.[41]

International NGOs provided support to mine action programs by providing capacity-building support on standards (particularly on land release) and information management, as well as directly conducting clearance operations and mine risk education in 2017. International NGOs were active in States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Colombia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia.

Croatia, which is on track to meet its Article 4 clearance obligations, did not receive international capacity-building or operational support in 2017, nor did Germany and the UK. In Chile, where no cluster munition survey or clearance has yet taken place, there was no international support in 2017.

Since 2015, Lebanon has been collaborating with the GICHD to manage and coordinate the Arab Regional Cooperation Programme for Mine Action.[42]

(For information about funding for cluster munition survey and clearance, see the Support for Mine Action sections of the online country profiles).[43]

Progress in signatories, non-signatories, and other areas

In general, there is much better knowledge of cluster munition contamination and more thorough reporting of land release activities in States Parties and signatories than in non-signatories. This underlines the importance of striving for universalization of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in order to improve global efforts to address the threat posed by cluster munition remnants.

Of the 13 non-signatories that are or may be affected, only Serbia has an understanding of the extent of contamination. This compares to eight of 13 States Parties that have an understanding of the extent of contamination. Nine non-signatories and one signatory do not know the extent of contamination.[44] In one non-signatory and one signatory it is not clear whether there is contamination.[45] In 2017, no data on survey or clearance was available for non-signatory Iran. Land release results were not comprehensive in five non-signatories (Cambodia, Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Vietnam).

All States Parties and signatories have a mine action program, authority, center, or other institution responsible for mine action. Non-signatory Syria does not have a national mine action program, authority, or center. Ukraine, also a non-signatory, has several bodies responsible for mine action, but as of mid-2018 still had to adopt a law that would create a national mine action institutional structure.

All three other areas (Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara) have a good understanding of the extent of contamination, available land release results, and established mine action programs or authorities.

Clearance in conflict

In 2017 and 2018, conflict continued to hinder land release activities in three States Parties (Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia), and six non-signatories (Libya, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen), as well as signatory DRC.

Afghanistan continued to report that some cluster munition-contaminated areas cannot be accessed due to insecurity.[46] In 2017, two conflict-related attacks were recorded against humanitarian deminers, which killed three and injured one, both in Nangarhar province.[47] Iraq’s response to cluster munition contamination has been eclipsed at a national level by the priority given to tackling densely mine-contaminated areas liberated from IS to permit the return of displaced populations.[48] In Somalia, survey of mines/ERW was being conducted in 2017 for the first time in all states, although movements were hampered at times by the high levels of insecurity.[49] In 2017, three mine action staff were abducted, with one shot and injured. They were later all released.[50]

In Libya, the Libyan Mine Action Centre (LibMAC) described the following challenges: the high level of contamination; ongoing conflict and the continued presence of IS; the difficulty in convincing internally displaced persons to delay their return until the ERW threat is addressed; security and access to priority areas continues to be problematic; limited ERW and improvised explosive device (IED) disposal capacity in Libya; the vast geographical area; and the shortfall in governmental and international support.[51] In 2017, most international organizations continued to provide capacity-building to national partners remotely from Tunisia. Only one international NGO returned to Libya in 2017. As of June 2018, NGOs were frequently forced to suspend operations in the south-west due to poor security.[52]

In South Sudan, cluster munition clearance decreased significantly due to a shift from area clearance to reactive EOD spot tasks because of security constraints.[53] This is in contrast to 2016 when a decision was made to deploy the bulk of capacity on cluster munition tasks, due to the need to clear areas for humanitarian access and for UN mission-related activities.[54] In 2017, internally displaced populations remained particularly vulnerable to cluster munition remnants and other explosive hazards as they moved across unfamiliar territory. Cluster munition contamination continued to limit access to agricultural land and increased food insecurity.[55] Mine action operators continued to face serious threats to the security of their operations and personnel due to the ongoing conflict. In 2017, there was an ambush on a demining contractor in which four personnel were seriously injured. There were also several instances of criminality in which teams were robbed by armed groups during the year.[56]

In Sudan, the extent of mine and ERW (including cluster munitions) contamination in areas of Abyei and the border area between Sudan and South Sudan remained unknown due to persistent conflict and ongoing restrictions on access.[57]In Syria, continuing conflict prevented a coordinated national program of mine action in 2017 though mine action interventions gathered significant momentum, albeit at levels that varied in different regions according to the level of security.

In Ukraine, the heaviest mine and ERW (including cluster munitions) contamination is believed to be inside the 15km buffer zone between the warring parties, but access to this area for survey and clearance operations is severely limited.[58]

In Yemen, communication and coordination between Yemen Mine Action Center (YEMAC) headquarters and its Aden branch have been hampered by Yemen’s de facto division between the Saudi-led coalition that controls Aden and operates in much of the south in support of the internationally recognised but exiled government, and Houthi rebels who control the capital Sana’a and operate in much of the north.[59] However, despite this, in 2017, UNDP reported that YEMAC administrative and operational capacity and productivity improved in 2017, as a result of training courses. [60]

In DRC, survey of possible cluster munition contamination in the Aru and Dungu territories is not possible due to security concerns.[61]

In Azerbaijan and Georgia, there may be cluster munition contamination in areas that are not under government control.[62] In Western Sahara, cluster munition strike areas located inside the buffer strip east of the Berm are inaccessible for clearance.[63]

Country Summaries

Where discrepancies between data sources exist, only one source has been utilized—usually the mine action center. (For complete information on all states, including details of data variations, see the online mine action country profiles at www.the-monitor.org/cp.)

States Parties

Afghanistan’s cluster munition contamination dates from use by Soviet and United States (US) forces and blocks access to agricultural and grazing land.[64] Most cluster munitions used by the US in late 2001 and early 2002 were removed during clearance operations in 2002–2003, guided by US airstrike data.[65] As of December 2017, Afghanistan recorded 6.52km2 of cluster munition-contaminated areas. Previously unidentified cluster munition-contaminated areas were added to the database in 2017, and it is possible that there are other as yet unknown areas.[66] In 2017, clearance was conducted by two national NGOs, Demining Agency for Afghanistan (DAFA) and AREA, and one international NGO, the HALO Trust.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s cluster munition contamination results from Yugoslav use in the 1992–1995 conflict after the break-up of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Cluster munitions were also used by NATO forces in Republika Srpska.[67] The total amount of contaminated land reduced to 6.47km2 at the end of 2017 from 7.3km2 at the end of 2016.[68] During 2017, three organizations conducted cluster munition technical survey and/or clearance: the BiH Armed Forces, the Federal Administration of Civil Protection, and NGO Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA).[69]

Chad is believed to be contaminated bycluster munitions used by France and Libya in the 1980s, but there are no identified suspected or confirmed hazardous areas. Large portions of the northern regions of Chad, which are heavily contaminated by mines and ERW, are still to be surveyed, and it is possible that they contain cluster munition-contaminated areas. No cluster munition survey or clearance was reported in 2017. The National Demining Center (Centre National de Déminage, CND) operates demining and EOD teams. In September 2017, the EU agreed to support a new four-year mine action project (PRODECO), which is comprised of survey and clearance, as well as capacity-building to the CND.[70]

Chile has reported military training areas totaling 97km2 that are suspected to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants. As of mid-2018, Chile had not reported conducting any survey or clearance of the cluster munition-contaminated areas, nor had it reported on any steps taken to elaborate a work plan.

Colombia has acknowledged that cluster munitions were used in the past.[71] The impact of any cluster munition contamination is believed to be minimal. In August 2016 and in May 2017, Colombia reported that it was in the process of establishing the location and extent of any contamination.[72] Colombia may be able to declare full completion of its Article 4 obligations once the requisite assessment and survey has been taken.

Croatia is contaminated by cluster munitions used in the 1990s conflict that followed the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia.[73] In 2017, the total contaminated area reduced by 0.7km2 through clearance to 1.74km2, despite the identification of four previously unknown contaminated areas totaling 1.0km2.[74] Croatia aims to complete clearance of all cluster munition contamination by the end of 2018.[75] Cluster munition clearance is conducted by commercial demining companies.[76]

Germany reportedin June 2011 that it had identified areas suspected of containing cluster munition remnants at a former Soviet military training range at Wittstock in Brandenburg. Non-technical survey resulted in a suspected area of approximately 11km2.[77] The area is completely perimeter-marked with warning signs and an official directive constrains access to it.[78] Survey was completed in 2015, and results formed the basis for subsequent preparatory work in 2016, including a fire protection system.[79] Clearance operations commenced in March 2017.[80] Although Germany intends to meet its August 2020 clearance deadline, it stated that several factors may lead to delays.[81]

In Iraq, cluster munition remnants contaminate significant areas of central and southern Iraq, a legacy of the 1991 Gulf War and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Iraq reports that cluster munition remnants cover 165km2 of confirmed and suspected hazardous areas across eight central and southern governorates: 98% is in just the three governorates of Basra, Muthanna, and Thi-Qar.[82] There are other areas that require survey to determine the extent of contamination.[83] In 2017, survey and clearance were conducted by the army, the civil defense, and the Regional Mine Action Center (RMAC) South, along with humanitarian operators Iraq Mine Clearance Organization (IMCO), Danish Demining Group (DDG), Humanity and Inclusion (HI, formerly Handicap International), NPA, Mines Advisory Group (MAG), and commercial operators.[84] Mine action operations continued to be overshadowed by conflict, and as in previous years, data deficiencies hindered an accurate determination of progress.

Lao PDR is the world’s most heavily contaminated state as a result of cluster bombs used by the US between 1964 and 1973, including more than 270 million submunitions.[85] The scale of contamination is not known. In 2016, Lao PDR committed to a nationwide survey with a view to producing Lao PDR’s first baseline estimate of cluster munition contamination by the end of 2021.[86] By May 2018, Lao PDR had confirmed approximately 500km2 of cluster munition contamination.[87] In 2017, survey and clearance operators included the Lao armed forces and five humanitarian operators—one national, UXO Lao, and four international (HALO Trust, HI, MAG, and NPA)—as well as several international and national commercial operators.

Lebanon’s four southern regions are affected by contamination resulting from cluster munitions use by Israel during the July–August 2006 conflict, while some parts of the country are also contaminated by cluster munitions used in the 1980s.[88] Previously unknown contaminated areas continued to be discovered in 2017, predominantly in southern Lebanon.[89] At the end of 2017, Lebanon’s known cluster munition contamination had increased to 24km2 of confirmed and suspected hazardous areas.[90] Cluster munition remnants continue to affect agriculture. Contamination is also reported to pose a risk for refugees from Syria.[91] Cluster munition clearance in 2017 was conducted by international operators DanChurchAid (DCA), MAG, and NPA; national operator Peace Generation Organization for Demining (POD); and the Engineering Regiment of the Lebanese Armed Forces.

Montenegro’s cluster munition contamination is the result of NATO airstrikes in 1999.[92] A non-technical survey conducted in 2012–2013 identified approximately 1.7km2 of suspected and confirmed hazardous areas in two municipalities and one urban municipality.[93] The contamination mainly affects infrastructure and utilities, accounting for 63% of the affected land, with agriculture accounting for another 30%. Two suspected areas remain to be surveyed.[94] In May 2018, funding was secured for survey and clearance of the remaining cluster munition contamination, to be conducted by NPA.[95]

In Somalia, Ethiopian National Defense Forces reportedly used cluster munitions in clashes with Somali Armed Forces along the Somali-Ethiopian border during the 1977–1978 Ogaden War.[96] In 2016, BL-755 submunitions were discovered, the result of alleged use by Kenya that year.[97] Cluster munition contamination is suspected in southcentral Somalia and Puntland, but the extent is not known. No survey or clearance of cluster munition remnants was conducted in 2017. However, in 2017 for the first time, mine/ERW teams were to be deployed in all states, although the number of teams was limited and movements hindered by insecurity.[98] Somalia had not submitted its initial Article 7 transparency report as of 1 August 2018.

United Kingdom (UK). There may be an unknown number of cluster munition remnants on the Falkland Islands/Malvinas as a result of the use of cluster munitions by the UK against Argentine positions in 1982. Most cluster munition contamination was cleared in the first year after the conflict.[99] The UK affirmed in 2015 that no areas known to be contaminated with cluster munition remnants exist outside areas already suspected of being contaminated with landmines or ERW, which are all marked and fenced.[100] In its second Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 extension request, the UK reported that by the end of March 2020, it is expected that an estimated 0.16km2 of mine contamination will remain. The UK has not said whether this remaining area is suspected to contain cluster munition remnants. In 2017, land release was conducted by BACTEC. No submunitions were found during clearance operations in 2017, although one empty BL755 cluster munition container was found.[101]

Non-signatories with more than 5km2 of contaminated land

The full extent of Cambodia’s contamination is not known. Cluster munition contamination is the result of the intensive US air campaign during the Vietnam War that concentrated on the country’s northeastern provinces along its border with Lao PDR and Vietnam.[102] In 2011, Thailand fired cluster munitions into Cambodia’s northern Preah Vihear province, which resulted in additional contamination of approximately 1.5 km2.[103] Cambodia estimates 624km2 of cluster munition contamination in 18 provinces.[104] Cambodia is conducting a national mine/ERW baseline survey, which it expects to complete by 2020. The Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA) plans to modify its survey procedures to use the Cluster Munition Remnants Survey (CMRS) methodology, which in 2017 was only used by NPA.[105] Survey and clearance of cluster munition remnants in eastern Cambodia are undertaken mainly by the Cambodian Mine Action Center (CMAC), NPA, and MAG.

South Sudan. From 1996 to 1999, prior to South Sudan’s independence, Sudanese government forces are believed to have air-dropped cluster munitions sporadically in southern Sudan.[106] New use of cluster munitions by an unidentified party resulted in additional contamination in 2014 of Jonglei state.[107] At the end of 2017, contamination was suspected across seven of 10 states.[108] It is thought that the actual size of contamination is greater than the recorded estimates of 4.54km2 of suspected and confirmed contamination.[109] However, ongoing insecurity, particularly in Greater Upper Nile region (Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile states), continued to prevent access to confirm or address cluster munition contamination.[110] UNMAS oversees mine action and supports the capacity development of the National Mine Action Authority (NMAA).[111] Three international NGOs (DCA, DDG, and MAG) and three commercial companies (G4S Ordnance Management, Mechem, and the Development Initiative) operated in 2017. The amount of cluster munition-contaminated land cleared decreased in 2017 due to a shift from area clearance to reactive EOD tasks because of security constraints.[112]

Syria. Cluster munitions have been used extensively since 2012, but the full extent of contamination is not known. Cluster munition use, casualties, and contamination have been reported in Aleppo, Idlib, Hama, Homs, Dara’a, Deir az Zour, and Quneitra governorates, as well as the Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta. Prior to the current conflict that began in 2012, the Golan Heights was contaminated by UXO, including unexploded submunitions. Syria does not have a national mine action authority or a national program for survey and clearance. Mine action has been conducted by a wide range of organizations, including military engineers of parties to the conflict, civil defense organizations, humanitarian demining organizations, and commercial companies. In 2015, UNMAS opened an office in Gaziantep and established a mine action sub-cluster to integrate mine action into the broader Syria humanitarian response. In September 2017, UNMAS opened an office in Beirut to coordinate support provided through offices in Gaziantep and Amman for 27 mine action organizations undertaking activities that included community-level contamination impact surveys, marking of some hazardous areas, risk education, and clearance.[113] International humanitarian and commercial operators were active mainly in northeastern Syria, and some international actors have partnered with Syrian organizations to provide training, funding, and support. Land release results are not systematically recorded. No cluster munition-contaminated hazardous areas have been recorded. However, the Syrian Civil Defence and its partner Mayday Rescue said that submunitions constituted the “vast majority” of items cleared in the course of conducting roving tasks in response to community requests.[114]

Ukraine.The full extent of contamination from cluster munitions used by both government and pro-Russian armed opposition forces in Ukraine’s eastern provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk from mid-2014 until a February 2015 ceasefire is not known. Prior to 2014, cluster munitions had never been used in Ukraine. Mine action operators consist of Ukrainian government authorities, three international NGOs (DDG, Fondation Suisse de Deminage, and HALO Trust), and a national NGO, Demining Team of Ukraine. Only HALO reported survey of cluster munition contamination in 2017.[115] No clearance of cluster munition remnants was reported. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and the GICHD are providing support to establish mine action legislation, policies, coordination, and information management.[116]

Vietnam is one of the most cluster munition-contaminated countries in the world as a result of the US use of cluster munitions in 1965–1973 in 55 provinces and cities.[117] The US military also abandoned substantial quantities of cluster munitions.[118] There is no national assessment of contamination, although an ERW impact survey completed in 2014, but not published until 2018, reported that cluster munition remnants affected 32 of Vietnam’s 63 provinces and cities.[119] In Quang Tri, reportedly Vietnam’s most contaminated province, the extent of contamination has become better known, as a result of survey. By the start of 2018, operators estimated total ERW contamination at more than 130km2, and with survey still to be conducted in three districts, it was expected the total would rise to between 150km2 and 200km2.[120] The military has conducted most clearance in the country over the past few years, but as in past years they did not provide data for 2017. Four NGOs (DDG, MAG, NPA, and PeaceTrees Vietnam) conducted land release in 2017.

Yemen. Since the start of the current conflict in March 2015, air strikes by the Saudi-led coalition have resulted in significant contamination that poses a threat to the civilian population.[121] YEMAC has identified heavy cluster munition contamination in Saada governorate as well as contamination in Amran, Hodaida, Mawit, and Sanaa governorates, including in Sanaa city.[122] Cluster munition contamination has also been reported in Hajjah governorate.[123] Contamination also results from use in 2009 and perhaps earlier. There are some 18km2 of suspected contamination with submunitions in the northern Saada governorate predating the current conflict.[124] The UNDP and YEMAC embarked on a plan for the next phase of cooperation covering 2017−2020. The plan’s “overarching principles” included aiding restoration of basic services, enabling access to infrastructure, and reducing casualties.[125] In 2017, YEMAC—the only operator—conducted survey and clearance on an emergency basis. It reported destroying 3,245 cluster munition remnants in 2017, although the amount of land cleared of cluster munition remnants was not disaggregated from land cleared from other ERW. Operations included response to requests for emergency clearance of Hodeida port, the main entry point for international humanitarian assistance to Yemen, and Amran cement factory, an important contributor to economic activity.[126]

Other areas with more than 5km2 of contaminated land

Kosovo is affected by cluster munitions used by Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Armed Forces in 1998–1999 and by a NATO air campaign in 1999.[127] After demining operations finished in 2001, the UN reported the problem as virtually eliminated.[128] However, subsequent surveys since 2008 have identified contaminated areas.[129] Land release in 2017 was conducted by the Kosovo Security Forces, HALO Trust, and NPA. Clearance results increased in 2017.

Most of Nagorno-Karabakh’s cluster munition contamination dates from use in 1992–1994 during armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Just more than 72km2 of cluster munition contamination affects all regions with over two-thirds of the contamination located in three regions: Askeran, Martuni, and Martakert.[130] All survey and clearance is conducted by HALO Trust. Clearance of cluster munition-contaminated land decreased significantly in 2017, as the clearance of mined areas was prioritized.[131] In 2016, 2km2 of new contamination was estimated to have resulted from use of cluster munitions in the hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan in April.[132] Clearance of this new contamination was completed in February 2017.[133]

[1] The Monitor acknowledges the contributions of the Mine Action Review (www.mineactionreview.org), which has conducted the primary mine action research in 2018 and shared all its country-level landmine reports (from “Clearing the Mines 2018”) and country-level cluster munition reports (from “Clearing Cluster Munition Remnants 2018”) with the Monitor. The Monitor is responsible for the findings presented online and in its print publications.

[2] States Parties with cluster munition remnants: Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Chile, Croatia, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Montenegro, Somalia, and the UK; signatories: Angola and DRC; non-signatories: Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Iran, Libya, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, Vietnam, and Yemen; and other areas: Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara.

[3] It is unclear whether there is cluster munition contamination in State Party Colombia and non-signatory Georgia.

[4] In some countries, some clearance results were not reported. In addition, in some countries—particularly those experiencing conflict—informal clearance took place and was not recorded.

[5] See chapter on Cluster Munition Ban Policy in this report. New use was also alleged to have occurred in Egypt and Libya.

[6] See mine action country profiles online for detailed information and sources available on the Monitor website, the-monitor.org/cp.

[7] In Armenia, in September–October 2017 during technical survey and battle area clearance in Kornidzor, two submunitions were found and destroyed during release of an area of 64,191m2. Email from Reuben Arakelyan, Director, Center for Humanitarian Demining and Expertise, 14 June 2018.

[8] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 4.

[9] Cluster Munition Monitor does not report on Action 3.4, “Be inclusive when developing the plan.” For Action 3.6, “Provide support, assist and cooperate,” see the Support for Mine Action profiles and annual Landmine Monitor reports.

[10] Emails from Nataša Mateković, Assistant Director and Head of Planning and Analysis Department, Croatian Mine Action Center (CROMAC), 22 March 2017; and from Davor Laura, CROMAC, 6 April 2018.

[11] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2017), Form F; and email from official from the Desk for Conventional Arms Control, German Federal Foreign Office, 7 May 2018.

[12] Emails from Brig.-Gen. Ziad Nasr, Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC), 27 April 2018; from LMAC Operations Department, 27 June 2018; and from Alauddin Mateen, Plans Officer, Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC), 15 July 2018.

[13] Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA), “Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro,” July 2013, p. 26; interview with Milovan Joksimović, Directorate for Emergency Situations, Podgorica, 15 May 2017; and email, 28 March 2018.

[14] Chile, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form F, July 2017, bit.ly/CCMArt7Chile17; and email from an official in the Arms Export Policy Department of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), 1 July 2015.

[15] The National Regulatory Authority (NRA), “From Survey to Safety, Quantifying and Clearing UXO Contamination in Lao PDR,” March 2016.

[16] Interviews with Phoukhieo Chanthasomboune, NRA, and Thipasone Soukhathammavong, UXO Lao, Vientiane, 2 May 2018.

[17] Email from Ahmed Al-Jasim, Head of Information Management Department, Directorate of Mine Action (DMA), 10 April 2018.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Convention on Cluster Munitions 8MSP Progress Report – monitoring progress in implementing the Dubrovnik Action Plan,” submitted by the President of the Eighth Meeting of States Parties, 9 July 2018, covers the period 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018, bit.ly/8MSPprogressReport. The Cluster Munition Monitor does not report on mine risk education.

[20] Germany, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form G, 4 April 2012; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2014), Form F, 20 April 2015, bit.ly/CCMArt7Germany15.

[21] Statement of the UK, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Standing Committee on Mine Action, Geneva, 27 May 2009, bit.ly/UKstatement09.

[22] Email from Davor Laura, CROMAC, 6 April 2018.

[23] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2017), Form F; and email from Alauddin Mateen, Plans Officer, DMAC, 15 July 2018.

[24] Montenegro, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2017), Form F.

[25] Email from Goran Zdrale, Bosnia and Herzegovina Mine Action Center (BHMAC), 17 May 2017; interview with Saša Obradovic, BHMAC, Sarajevo, 10 May 2017; and statement of GICHD, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 7 June 2018.

[26] NRA, “From Survey to Safety, Quantifying and Clearing UXO Contamination in Lao PDR,” March 2016.

[27] LMAC, “Lebanon Mine Action Strategy. Second Milestone Review 2014–2016,” March 2018; and email from Brig.-Gen. Nasr, LMAC, 27 April 2018.

[28] Email from official from the Desk for Conventional Arms Control, German Federal Foreign Office, 7 May 2018.

[29] Ibid.

[30] The National High Commission for Demining (Haut Commissariat National de Déminage, HCND), “Mine Action Plan 2014–2019,” May 2014, p. 4, bit.ly/HCNDplan1419.

[31] Email from Ahmed Al-Jasim, DMA, 10 April 2018.

[32] Second Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 Extension Request, 29 March 2018.

[33] Colombia, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form J; and Colombia, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2017), Form F, bit.ly/CCMArt7Colombia18.

[34] Email from Claus Nielsen, NPA, 18 June 2018.

[35] “Somalia National Mine Action Strategic Plan,” Draft Version, February 2018.

[36] This action requires that, “States parties will promote and continue to explore methods and technologies which will allow clearance operators to work more efficiently with the right technology to achieve better results as we all strive to attain as quickly as possible the strategic goal of a world free of cluster munitions and its remnants, while also making full use of existing methods and technologies that have proven to be effective.” Dubrovnik Action Plan, Implementation Support Unit of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, undated, p. 13.

[37] See table above, “Cluster Munition Land Release in States Parties.”

[38] See UNMAS Program list at www.mineaction.org/programmes.

[39] Interview with Olivier Bauduin, UNDP, Vientiane, 2 May 2018.

[40] Statement of GICHD, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 7 June 2018.

[41] Email from Camilo Serna, Vice Director, Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines, 18 July 2018.

[42] Email from Anna-Lena Schluchter, containing data from Rana Elias, Focal Point for Lebanon, GICHD, 21 June 2017.

[43] Available on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org/cp.

[44] The extent of contamination is not known in non-signatories: Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Iran, Libya, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, Vietnam, and Yemen; and signatory DRC.

[45] In non-signatory Georgia there may be some contamination in South Ossetia, which is outside government control. In signatory Angola there is no confirmed contamination, but minimal contamination may remain.

[46] Email from Alauddin Mateen, Plans Officer, DMAC, 15 July 2018.

[47] ANAMA, “Afghanistan Annual Report on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict: 2017,” p. 18.

[48] Email from Ahmed Al-Jasim, DMA, 10 April 2018.

[49] Email from Claus Nielsen, Programme Manager, NPA, 22 March 2018.

[50] Emails from Ghirmay Kiros, UNMAS, 20 and 24 June 2018.

[51] PowerPoint presentation by Mohammad Turjoman, LibMAC, at the National Programme Director’s Meeting, Geneva, 8 February 2017.

[52] Telephone interview with Darren Devlin, DDG, 20 June 2018.

[53] Emails from Tim Lardner, UNMAS, 27 February and 1 March 2018.

[54] Email from Robert Thompson, UNMAS, 7 June 2017.

[55] UNMAS, “2018 Portfolio of Mine Action Projects: South Sudan,” undated.

[56] Emails from Richard Boulter, UNMAS, 6 June 2018; and from Tim Lardner, UNMAS, 27 February and 1 March 2018.

[57] UNMAS, “2018 Portfolio of Mine Action Projects, Sudan,” undated.

[58] Emails from Yuri Shahramanyan, Programme Manager, HALO Trust Ukraine, 24 May 2017; and from Henry Leach, Head of Programme, DDG Ukraine, 29 May 2017.

[59] Interview with Ahmed Alawi, YEMAC, and Stephen Bryant, Chief Technical Adviser, UNDP, in Geneva, 17 February 2016.

[60] UNDP, “Emergency Mine Action Project, Annual Report 2017,” January 2018, pp. 10−12.

[61] “Stratégie Nationale de Lutte Antimines en République Démocratique du Congo 2018–2019,” CCLAM, November 2017, pp. 18–19.

[62] In Azerbaijan, around one-fifth of the territory is occupied by Armenia. In Georgia, South Ossetia is occupied by Russia and inaccessible to both the Georgian authorities and international NGO clearance operators.

[63] The buffer strip is an area 5km wide, east of the Berm. MINURSO, “Ceasefire Monitoring Overview,” undated, minurso.unmissions.org/ceasefire-monitoring.

[64] Statement of Afghanistan, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 15 April 2013, bit.ly/CMCintersessional13Afghanistan.

[65] HRW and Landmine Action, Banning Cluster Munitions: Government Policy and Practice (Mines Action Canada, Ottawa, May 2009), p. 27; and interviews with demining operators, Kabul, 12–18 June 2010.

[66] Email from Alauddin Mateen, DMAC, 15 July 2018.

[67] NPA, “Implementation of the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM) in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” Sarajevo, undated but 2010, provided by email from Darvin Lisica, NPA, 3 June 2010.

[68] Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2017), Form F; and email from Ljiljana Ilić, BHMAC, 22 June 2018. The total contamination reported for the end of 2016 has been revised to 7.3km2. In Cluster Munition Monitor 2017 it was reported incorrectly as 8.42km2.

[69] Email from Ljiljana Ilić, BHMAC, 22 June 2018.

[70] Email from Romain Coupez, MAG, 3 May 2017; and HI “Country Profile Chad,” September 2017, www.handicapinternational.be/sites/default/files/paginas/bijlagen/201710_fp_tchad_fr.pdf.

[71] C. Osorio, “Colombia destruye sus últimas bombas de tipo racimo” (“Colombia destroys its last cluster bombs”), Agence France-Presse, 7 May 2009; and Ministry of National Defense presentation on cluster munitions, Bogotá, December 2010.

[72] Colombia, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (initial report submitted in August 2016), Form F; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form J, bit.ly/CCMArt7Colombia16.

[73] CROMAC, “Mine Action in Croatia and Mine Situation,” undated, www.hcr.hr/en/minSituac.asp.

[74] Email from Dejan Rendulić, CROMAC, 14 June 2018; and Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2017), Form F.

[75] Email from Davor Laura, CROMAC, 6 April 2018.

[76] CROMAC website, “CROMAC’s Mine Information System,” undated, www.hcr.hr/pdf/MISWebENG.pdf; and email from Davor Laura, CROMAC, 6 April 2018.

[77] Germany, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2014), Form F, 20 April 2015, bit.ly/CCMArt7Germany15.

[78] Ibid.; and Germany, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report, Form G, 4 April 2012, bit.ly/CCMArt7Germany12.

[79] Email from official from the Desk for Conventional Arms Control, German Federal Foreign Office, 19 April 2017; and Germany, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form F, bit.ly/CCMArt7Germany17.

[80] Emails from official from the Desk for Conventional Arms Control, German Federal Foreign Office, 19 April and 13 June 2017; and Germany, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form F, bit.ly/CCMArt7Germany17.

[81] Email from official from the Desk for Conventional Arms Control, German Federal Foreign Office, 7 May 2018.

[82] Email from Ahmed Al-Jasim, DMA, 10 April 2018.

[83] Emails from Khatab Omer Ahmed, Planning Manager, Directorate General of Technical Affairs, Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA), 8 May 2018; and from Steven Warner, Desk Officer, MAG, 10 April 2018.

[84] Email from Ahmed Al-Jasim, DMA, 10 April 2018.

[85] “US bombing records in Laos, 1964–73, Congressional Record,” 14 May 1975; NRA, UXO Sector Annual Report 2009 (Vientiane, 2010), p. 13, bit.ly/NRAUXOrep09; and Lao PDR, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2013), Form F, bit.ly/CCMArt7LaoPDR14.

[86] NRA, “From Survey to Safety, Quantifying and Clearing UXO Contamination in Lao PDR,” March 2016.

[87] Interview with Phoukhieo Chanthasomboune, NRA, and Thipasone Soukhathammavong, UXO Lao, Vientiane, 2 May 2018.

[88] LMAC, “Lebanon Mine Action Strategy 2011–2020,” September 2011, bit.ly/LMACStrategySept2011; and responses to NPA questionnaire by Brig.-Gen. Elie Nassif, LMAC, 12 May and 17 June 2015.

[89] Emails from Brig.-Gen. Nasr, LMAC, 27 April 2018; and from LMAC operations department, 27 June 2018.

[90] Email from Brig.-Gen. Nasr, LMAC, 24 April 2017.

[91] Ibid., 27 April 2018; Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for 2017), Form I; statement of Lebanon, Convention on Cluster Munitions Seventh Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 4–6 September 2017; and LMAC, “Lebanon Mine Action Strategy. Second Milestone Review 2014–2016,” March 2018.

[92] NPA, “Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro,” July 2013, p. 21, bit.ly/NPARemnantsMontenegro.

[93] Montenegro, Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2014), Form F, bit.ly/CCMAct7Montenegro15; Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2013), Form F; and NPA, “Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro,” July 2013, p. 26, bit.ly/NPARemnantsMontenegro. There is a discrepancy in the locations reported as contaminated between the Article 7 reports and NPA.

[94] NPA, “Cluster Munition Remnants in Montenegro,” July 2013, p. 26; interview with Milovan Joksimović, Directorate for Emergency Situations, Podgorica, 15 May 2017; and email, 28 March 2018.

[95] Email from Jonas Zachrisson, NPA BiH, 21 June 2018.

[96] UNMAS, “UN-suggested Explosive Hazard Management Strategic Framework 2015–2019,” undated, provided by email from Kjell Ivar Breili, Project Manager, Humanitarian Explosive Management Project, UNMAS Somalia, 7 July 2015; and email from Mohammed Abdulkadir Ahmed, Somali National Mine Action Authority (SNMAA), 17 April 2013.

[97] UN Security Council, “Letter dated 7 October 2016 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992) and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea addressed to the President of the Security Council,” S2016/919, 31 October 2016, pp. 171–173.

[98] Email from Claus Nielsen, NPA, 22 March 2018.

[99] Letter to Landmine Action from Lt. Col. Scott Malina-Derben, Ministry of Defense, 6 February 2009.

[100] Email from an official in the Arms Export Policy Department of the FCO, 1 July 2015.

[101] Interview with an official in the Arms Export Policy Department of the FCO, London, 16 March 2017; and email, 2 June 2017.

[102] South East Asia Air Sortie Database, cited in D. McCracken, “National Explosive Remnants of War Study, Cambodia,” NPA in collaboration with the Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA), Phnom Penh, March 2006, p. 15; HRW, “Cluster Munitions in the Asia-Pacific Region,” April 2008, bit.ly/HRWCMinAsiaPacific; and HI, Fatal Footprint: The Global Human Impact of Cluster Munitions (HI, Brussels, November 2006), p. 11, bit.ly/HIFatalFootprint2006.

[103] Aina Ostreng, “Norwegian People’s Aid clears cluster bombs after clash in Cambodia,” NPA, 19 May 2011, bit.ly/NPACambodia2011.

[104] Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for 2017), Annex B; and email from the CMAA, 22 May 2018. However, its National Mine Action Strategy says known cluster munition contamination covers 645km2 and believes the figure will rise as a result of future survey. See, CMAA, “National Mine Action Strategy 2018−2025,” p. 9.

[105] Interview with Prum Sophakmonkol, CMAA, 24 April 2018.

[106] Cluster Munition Monitor, “Country Profile: South Sudan: Cluster Munition Ban Policy,” updated 23 August 2014, bit.ly/CMMSSudanBanPolicy14. See also, UNMAS, “Reported use of Cluster Munitions South Sudan February 2014,” 12 February 2014; and UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), “Conflict in South Sudan: A Human Rights Report,” 8 May 2014, p. 26, bit.ly/UNMISSReport14.

[107] UNMAS, “Reported use of Cluster Munitions South Sudan February 2014,” 12 February 2014. See also, UNMISS, “Conflict in South Sudan: A Human Rights Report,” 8 May 2014, p. 26, bit.ly/UNMISSReport14.

[108] Emails from Tim Lardner, UNMAS, 27 February and 1 March 2018.

[109] Emails from Tim Lardner, UNMAS, 27 February and 1 March 2018. According to UNMAS, the number of cluster munition strikes recorded is thought to be accurate, however the size of the strike area is likely greater than currently recorded estimates.

[110] UNMAS, “2017 Portfolio of Mine Action Projects: South Sudan,” January 2017.

[111] South Sudan, “South Sudan National Mine Action Strategic Plan 2012–2016,” Juba, 2012, p. iv, bit.ly/SSudanMineActionPlan1216.

[112] Emails from Tim Lardner, UNMAS, 27 February and 1 March 2018.

[113] Interview with Gilles Delecourt, UNMAS, Geneva, 16 February 2018; and email, 22 May 2018; UNMAS, “Programmes in Syria,” updated March 2018, at www.mineaction.org/programmes/syria.

[114] Telephone interview with Luke Irving, Mayday Rescue, 28 March 2018; and Mayday Rescue, “Syria Civil Defence, Explosive Hazard Mitigation Project Overview, Nov 2015–Mar 2018,” 1 March 2018.

[115] Email from Yuri Shahramanyan, HALO Trust Ukraine, 15 June 2018.

[116] “Mine Action Activities,” Side-event presentation by Amb. Vaidotas Verba, Head of Mission, OSCE Project Coordinator in Ukraine, at the 19th International Meeting, 17 February 2016; and email from Miljenko Vahtaric, OSCE Project Coordinator, 26 June 2017.

[117] “Vietnam mine/ERW (including cluster munitions) contamination, impacts and clearance requirements,” presentation by Sr. Col. Phan Duc Tuan, People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), in Geneva, 30 June 2011.

[118] Interview with Sr. Col. Phan Duc Tuan, PAVN, in Geneva, 30 June 2011.

[119] Vietnam National Mine Action Center (VNMAC), “Report on Explosive Remnants of War Contamination in Vietnam Based on the ‘Vietnam Explosive Remnants of War Contamination Survey and Mapping – Phase 1 Project,’” Hanoi, 2018, p. 38.

[120] Interviews with Resad Junuzagic, Country Director, Jan Eric Stoa, Operations Manager, and Magnus Johansson, Operations Manager, NPA, Hanoi, 17 April 2018; and with Simon Rea, Country Director, and Michael Raine, Technical Operations Manager, MAG Quang Tri, 19 April 2018.

[121] See Cluster Munition Ban Policy profile for Yemen, at www.the-monitor.org/cp.

[122] Interviews with Ahmed Alawi, YEMAC, 17 February 2016; and with Stephen Bryant, Chief Technical Adviser, UNDP, Geneva, 6 February 2017.

[123] Amnesty International, “Yemen: children among civilians killed and maimed in cluster bomb ‘minefields,’” 23 May 2016, bit.ly/AmnestyYemen23May2016.

[124] Email from Ali al-Kadri, General Director, YEMAC, 20 March 2014.

[125] UNDP, “Emergency Mine Action Project, Annual Report 2017,” January 2018, p. 12.