Cluster Munition Monitor 2018

Victim Assistance

Introduction

The adoption of the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions saw the first multilateral treaty to make the provision of assistance to victims of a specific weapon a formal obligation for all States Parties with victims.[1]

A decade later, the convention continues to set the highest standards for victim assistance. It requires States Parties with cluster munition victims to implement specific activities to ensure that adequate assistance is provided.[2]

As noted in the lead-up to the adoption of the text of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, the proposed convention aimed to reaffirm and build on existing international instruments. The ICRC observed that “past efforts of the international community and the work and research of organizations on mines and ERW have helped illuminate the needs of those who survive injuries caused by these weapons.”[3]

The Convention on Cluster Munitions extended the scope and understanding of victim assistance that had developed under the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty by codifying the international understanding of victim assistance and its components and provisions in Article 5.[4]

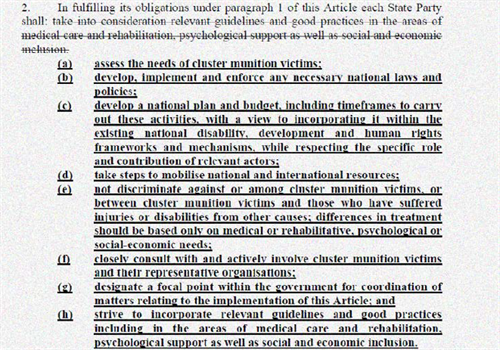

As can be seen in the final text adopted in 2008, the legal provision on victim assistance in the Convention on Cluster Munitions moved beyond the notion of requiring only the consideration of guidelines and good practices, as found in some earlier proposals, to a concrete list of obligations to act upon. This can be seen in the following image of a document from the 2008 Dublin Conference, where implementation points in the victim assistance article are shown with changes.

Article 5[5]

Victim Assistance

Note: Old text removed with strike through and additions are in bold and underlined.

Norms and relevant instruments

The provisions of the Convention on Cluster Munitions further strengthened the growing norm of victim assistance, including by influencing the victim assistance commitments in Protocol V of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) through its Plan of Action on Victim Assistance (2008). The victim assistance standard was again adapted, although in a less comprehensive form, in the text of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (2017).[6] Additionally, the Safe Schools Declaration (2015)—a non-binding political commitment that endorses the associated guidelines for protecting schools and universities from military use during armed conflict—includes states’ commitment to “make every effort at a national level…to provide assistance to victims, in a non-discriminatory manner.”[7] The declaration has particular relevance to cluster munition victims. As noted in previous Cluster Munition Monitor reports, many casualties from cluster munition attacks in Syria and Yemen were recorded in and near schools and other protected objects, including hospitals. The Monitor also reported many instances of civilian casualties caused by cluster munition attacks hitting schools, hospitals, and markets prior to entry into force of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in 2010.[8]

|

Cluster munition victims

“Cluster munition victims means all persons who have been killed or suffered physical or psychological injury, economic loss, social marginalisation or substantial impairment of the realisation of their rights caused by the use of cluster munitions.” (Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 2.1)

Cluster munition victims include those persons directly impacted by cluster munitions (survivors and persons killed) as well as affected families and communities.

Cluster munition survivors are persons who were injured by cluster munitions or their explosive remnants and lived. Most cluster munition survivors are also persons with disabilities.

Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments, which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.

|

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with victims under their jurisdiction are legally bound to implement adequate victim assistance in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law. All except two States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with cluster munition victims (Lao PDR and Lebanon) are also party to the Mine Ban Treaty and, as such, have also made victim assistance commitments through the Mine Ban Treaty’s action plans. In total, 63 States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions are also High Contracting Parties to CCW Protocol V. [9]

The requirement to apply human rights law has been understood foremost in terms of enhancing implementation through the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), by including victim assistance in national disability rights-related coordination structures. Most States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with cluster munition victims are also States Parties to the CRPD; Lebanon and Chad are signatories and Somalia is a non-signatory. Overall, among the 103 States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, 92% are also party to the CRPD,[10] while another three are signatories.[11]

Non-discrimination

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions should ensure that efforts to fulfill the obligations of the convention do not discriminate against or among cluster munition victims and those who have suffered injuries or impairments by other causes.[12] The Monitor has not identified discrimination specifically in favor of cluster munition victims by States Parties with Article 5 obligations since entry into force of the convention. In most countries—not only States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions—war veterans with disabilities are assigned financial allowances and other state benefits that are higher than those of civilian war survivors and other persons with disabilities. In taking a rights-based approach to victim assistance, States Parties need to be mindful of the requirement not to remove existing rights, as set out in Article 4.4 of the CRPD: “Nothing in the present Convention shall affect any provisions which are more conducive to the realization of the rights of persons with disabilities and which may be contained in the law of a State Party or international law in force for that State.”[13]

With regard to discrimination, the preamble of the Convention on Cluster Munitions also highlights the close relationship between the convention and the CRPD obligation to prevent another type of discrimination, not concerning differences in the cause of impairments and disability, but “discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability.”[14] The CRPD’s Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities released General Comment 6 on CRPD Article 5 (CRPD GC.6), regarding equality and non-discrimination in 2018.[15] Concerning non-discrimination in situations of risk and humanitarian emergencies (CRPD Article 11), the committee made a specific reference with relevance to victim assistance, stating that: “Non-discrimination must be ensured in situations of risk and humanitarian emergencies, based also on obligations in international humanitarian law, including humanitarian disarmament law, to address the increased risk inherent in such situations, of discrimination against persons with disabilities.”[16]

Guidance on good practices for taking a non-discriminatory integrated approach to victim assistance has been available since 2016.[17] The elements of the dual approach are to:

- Ensure that as long as specific victim assistance efforts are implemented, they improve the inclusion and wellbeing of survivors, other persons with disabilities, indirect victims, and other vulnerable groups; and

- Ensure that broader efforts actually do reach the survivors and indirect victims among the beneficiaries.[18]

This approach is recommended to be implemented until “mainstream efforts” are demonstrated to be inclusive of survivors and indirect victims, and fulfill the obligations that states have toward these groups.[19]

The Dubrovnik Action Plan

This summary highlights developments and challenges in States Parties half-way through the five-year Dubrovnik Action Plan period. The Dubrovnik Action Plan adopted by States Parties at the Convention on Cluster Munitions’ First Review Conference in September 2015 elaborates on the convention’s victim assistance obligations, and in doing so, lays out broad objectives to be achieved by the time of the Second Review Conference in 2020. The present chapter reports primarily on the efforts, endeavors, and challenges in implementing victim assistance in 14 States Parties with responsibility for cluster munition victims to which Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 5 and the action plan commitments are applicable, as listed in the table.

|

States Parties with cluster munitions victims |

|

Afghanistan |

|

Albania |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) |

|

Chad |

|

Colombia |

|

Croatia |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

|

Iraq |

|

Lao PDR |

|

Lebanon |

|

Montenegro |

|

Mozambique |

|

Sierra Leone |

|

Somalia |

In summary, several States Parties reported greater efforts to improve the quality and quantity of health and physical rehabilitation programs for survivors. However, few new initiatives to fill existing gaps in services were reported and in most countries survivor organizations and service providers noted that more services, better coordination, and greater integration into national systems were still crucial areas of need.

Although the majority of existing coordination mechanisms had some survivor participation, it was rarely evident that there was close consultation with victims nor was it clear how their views were taken into account in decision-making.

States Parties and service providers alike highlighted the lack of financial resources, which particularly impacted on the ability of survivor networks and others to provide income-generating activities and psychological assistance to cluster munition victims.

States Parties reporting on victim assistance—which may also be used by donors to identify priority areas—was made by most relevant states. However, States Parties were yet to link reporting on victim assistance with reporting on the CRPD as they had committed to doing in the Dubrovnik Action Plan following significant discussion on the issues of synergies in reporting and subsequent guidance on good practices to that effect.

Data on the provision of victim assistance in States Parties, signatory states, and non-signatories to the Convention on Cluster Munitions is available online in Monitor country profiles and in the Landmine Monitor report. A collection of thematic overviews, briefing papers, factsheets, and infographics related to victim assistance produced since 1999, as well as the latest key country profiles, is available through the victim assistance portal on the Monitor website.[20]

Improvement in the Quality and Quantity of Assistance

Ongoing data collection

The Dubrovnik Action Plan calls for ongoing assessment of the needs of cluster munition victims.[21]

In the following countries, assessment and data disaggregated by sex and age was generally available to all relevant stakeholders, and its use in program planning continued to be reported: Albania, Afghanistan, BiH, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon. BiH, Croatia, and Lebanon needed to update, revise, or combine victim databases. Further survey was needed in order to identify cluster munition victims and/or needs in Chad, Sierra Leone, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Montenegro, and Mozambique, as well as to confirm if there are victims in Mauritania and Zambia. In Afghanistan, where the last national disability survey was carried out in 2005, a plan for nationwide disability survey developed in 2016 remained unfunded into 2018. BiH continued to report that more survey was needed to establish detailed information on cluster munition victims, specifically those who had already been identified through initial survey.

Plans and coordination

Among States Parties with cluster munition victims, only Sierra Leone did not have a victim assistance focal point. However, to date, States Parties that have reported designated focal points have not been reporting on the ways in which those focal points for victim assistance have the necessary “authority, expertise and adequate resources” for the role, as called for in the Dubrovnik Action Plan.[22]

Coordination of victim assistance activities by States Parties with Article 5 obligations can be situated within existing coordination systems, including those created for the CRPD, or states can establish a specific coordination mechanism.[23] Through the Dubrovnik Action Plan, States Parties without a national disability action plan committed to draft a disability or victim assistance plan before the end of 2018.[24] At least seven of the States Parties with cluster munition victims were yet to develop, adopt, or approve, a plan as of the end of 2017.

Victim assistance planning in 2017–2018

|

State Party |

Plan for victim assistance |

|

Afghanistan |

No |

|

Albania |

Yes |

|

BiH |

Yes |

|

Chad |

(Revised for 2016–2020, but not yet adopted) |

|

Colombia |

Yes |

|

Croatia |

(Plan expired in 2014) |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

(Inactive) |

|

Iraq |

Yes (Annual planning) |

|

Lao PDR |

Yes |

|

Lebanon |

Yes |

|

Montenegro |

No |

|

Mozambique |

Yes |

|

Sierra Leone |

No |

|

Somalia |

No |

Involvement of Victims

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions have committed to actively include cluster munition victims and their representative organizations in policy-making and decision-making, so that their participation is made sustainable and meaningful.[25]

The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities reported that it continues “to observe an important gap between the goals and the spirit of both articles and the scope of their implementation due to, among others, the absence of consultation with and involvement of persons with disabilities through their representative organizations in the development and implementation of policies and programmes.”[26] In 2018, the committee emphasized the important role that organizations of persons with disabilities must have in the implementation and monitoring of that convention. The committee also noted that “States parties must ensure that they consult closely and actively involve such organizations, which represent the vast diversity in society, including…victims of armed conflicts. Only then can it be expected that all discrimination, including multiple and intersectional discrimination, will be tackled.”[27]

In most States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, survivors were engaged in relevant activities, but as is the case for persons with disabilities more generally, there was rarely any indication that survivor input was acted upon, and survivors’ representative organizations and other service providers reported in some states that the views of survivors were not actually considered.

In BiH, a victim assistance coordination body was officially established on 23 May 2018. Survivors’ representatives were involved in the two unofficial coordination meetings held in 2017 and advocated for official coordination. In 2017, Croatia did not hold any victim assistance coordination meetings, but survivors occasionally participated in the work of governmental and non-governmental bodies. A planned review by consultants of victim assistance in Somalia has the potential for increasing opportunities for survivor representation, since the only coordination meeting on victim assistance was held in 2014. Guinea-Bissau, Montenegro, and Sierra Leone remained the only states where the Monitor has not identified any survivor involvement in victim assistance activities since entry into force of the Convention on Cluster Munitions. However, disabled peoples’ organizations (DPOs) in all three countries advocated for the rights of all persons with disabilities.

Survivor networks and sustainability

To strengthen sustainability and the effective delivery of services, States Parties have committed to enhance the capacity of organizations representing survivors and persons with disabilities, as well as national institutions.[28] The Monitor identified the following states and areas with cluster munition casualties where survivor networks reported developments in 2017 and into 2018, as seen in the table below.

Survivor networks active in 2017–2018

|

States Parties |

Non-signatories and other areas |

|

Afghanistan |

Cambodia |

|

Albania |

Eritrea |

|

BiH |

Ethiopia |

|

Colombia |

Serbia |

|

Croatia |

Tajikistan |

|

Iraq |

Vietnam |

|

Mozambique |

Yemen |

|

Somalia |

Western Sahara |

|

Signatories |

|

|

Angola |

|

|

DRC |

|

|

Uganda |

Disappointingly, in most countries, survivor networks struggled to maintain their operations with decreasing resources available. Networks in States Parties Croatia, Mozambique, and Somalia were largely unable to implement essential activities in much of 2017 and 2018. Activities of the national survivor network in Afghanistan were primarily advocacy and awareness-raising.

Availability and Accessibility of Assistance

States Parties responsible for cluster munition victims have the obligation to adequately provide assistance.[29] Such assistance should be age- and gender-sensitive.[30] The Dubrovnik Action Plan also calls for the review of the availability, accessibility, and quality of existing services, and identification of the barriers that prevent access.[31]

Resources

The Convention on Cluster Munitions, and victim assistance in humanitarian disarmament more broadly, has contributed to making more resources available to survivors as well as people with similar needs—mostly persons with disabilities.[32] However, there has been little indication that other major resource frameworks have begun to substantially fill gaps where earmarked funding for victim assistance is lacking.

At the time of drafting of the convention, the NGO Landmine Survivors Network stated: “Victim Assistance does not require creation of new systems or mechanisms. It is merely necessary that the existing public services and systems operate in a manner that will ensure that victims of cluster munitions as part of the larger group of people with disabilities can enjoy their human rights. Highlighting this view will facilitate more efficient implementation of State Party’s treaty obligations, provide greater opportunities for resource mobilization and ensure consistency in measures taken.”[33]

Yet, despite similarly optimistic statements by donors and affected states over the years, a decade after the convention was adopted many States Parties with cluster munition victims are facing inadequate funding of state services (where they do exist) and declining resources for the work of international organizations, national and international NGOs, and DPOs that deliver most direct assistance to cluster munition victims.

In 2017–2018, significant funding shortages severely hindered victim assistance implementation in States Parties including: Afghanistan, Chad, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Mozambique, and Somalia. In States Parties that have fewer recorded cluster munition victims and are also party to the CRPD, such as Montenegro and Sierra Leone, it could be assumed that national disability rights mechanisms would cover the needs of cluster munition survivors. However, in both cases, implementation of CRPD-based legislation has stalled or is not adequately covering the rehabilitation services that would address the needs of survivors.

In some instances in 2017 and 2018, special measures were employed to meet immediate needs. For example, in Afghanistan, an emergency victim assistance fund was organized through Afghanistan’s Common Humanitarian Fund and implemented by the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), targeting the basic needs of beneficiaries left without assistance following the operational conclusion of a multi-year program for conflict victims. Also, in Chad, Humanity & Inclusion (formerly Handicap International, HI) created a social fund for mine/ERW victims, persons with disabilities, and vulnerable persons.

Many states not party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, including signatories, also have seen funding to victim assistance decline in recent years.

The Dubrovnik Action Plan commits to promote further cooperation and assistance for projects relevant to cluster munition victims through existing mechanisms in accordance with Article 6 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

The CRPD’s Article 32 on international cooperation recognizes the importance of support for national efforts between and among states and in partnership with other organizations, in particular DPOs. The Global Action on Disability (GLAD) Network is a coordination body of bilateral and multilateral donors and agencies, the private sector, and foundations working to enhance the inclusion of persons with disabilities in international development and humanitarian action.

Regarding potential resourcing opportunities, five years ago when intersessional meetings were part of the Convention on Cluster Munitions machinery, theOffice of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights informed the 2013 meeting about the possibilities for accessing the United Nations Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNPRPD) Disability Fund.[34] Subsequently, UNPRPD funding to State Party Mozambique contributed to victim assistance efforts through 2014.[35] Currently, non-signatory Tajikistan is benefiting from the grant in a way that could increase accessibility for cluster munition victims.[36]

These mechanisms have the potential to assist states in fulfilling their obligations to cluster munition victims.

Impact of conflict on service provision

Continued conflict has significantly negatively impacted possibilities for providing effective assistance, including in States Parties Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia. For example, in Afghanistan, access to some ICRC rehabilitation centers was briefly suspended due to severe security incidents and security constraints made the organization stop its outreach services. Specific challenges to victim assistance in Iraq included the instability of the security situation in the areas freed from the non-state armed group Islamic State (IS). In Somalia, a massive devastating vehicle-borne explosive caused hundreds of casualties, further stretching the resources of overwhelmed health services in Mogadishu.

In some States Parties facing conflict and insecurity—including those noted above as well as states not party Syria and Yemen, both with recent cluster munition casualties—the national or subnational humanitarian response Health Cluster coordinates priorities and response strategies.[37] This is conducted with the guidance of lead agencies, and is sometimes integrated into or operates parallel to victim assistance coordination.[38]

Humanitarian action concerns protecting life and health, and alleviating suffering caused by conflict, or natural and human-induced disasters. According to the principles of humanitarian action, human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found and carried out on the basis of need alone. Thus, humanitarian action must be independent from the political, economic, military, or other such strategic objectives.[39] An Inter-Agency Standing Committee Task Team on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action is developing guidelines for the inclusion of persons with disabilities into humanitarian action, that encompasses issues related to protection of survivors and the implementation of victim assistance, which it planned to launch in 2018.[40] The guidelines respond to the charter on inclusion of persons with disabilities adopted at the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016.[41]

Healthcare and rehabilitation, including prosthetics

The right to the highest attainable standard of healthcare, first articulated in the World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution (1946), is found in a number of human rights instruments including Article 25 of the CRPD. The UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, with the support of the government of Finland, hosted an expert group meeting on the rights of persons with disabilities to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental healthin Geneva, Switzerland, in May 2018. The UN Special Rapporteur was also preparing a study on the issue to be presented at the UN General Assembly in October 2018.

In January 2018, the WHO held a general consultation outlining its activities for the next three years. This includes: integrating rehabilitation into universal health coverage (UHC) budgeting and planning; developing a package of priority rehabilitation interventions; and establishing tools and resources to strengthen the health workforce for rehabilitation.[42] The WHO released recommendations on health-related rehabilitation linked to the Sustainable Development Goals in 2017.[43]

All the States Parties with cluster mention victims had some forms of ongoing healthcare and rehabilitation available. Some have yet to systematically integrate rehabilitation into health system funding and planning. Many need to simplify the process of applying for new or replacement prosthetic devices. It was reported that intensified efforts to improve access to rehabilitation services in remote and rural areas (including allocating resources to take beneficiaries to rehabilitation centers and ensuring that transport is available) are needed in Iraq and Chad. In Afghanistan, there has been a notable increase in the number and geographic availability of physical rehabilitation centers over the past five years, but more centers are still needed. A survivors’ organization in BiH provided legal support referrals to rehabilitation service providers to assist survivors in overcoming bureaucratic barriers. In Guinea-Bissau, there continued to be only one physical rehabilitation center for the entire country. The ICRC has entered into a multi-year agreement with the health ministry in Lao PDR for the development of sector-wide standards for prosthetic devices to improve service delivery. Lebanon reported that national standards for prosthetic devices had been established. In Mozambique, prosthetics where only available in the capital, and the supply was limited. In Sierra Leone, it was reported that prosthetic centers were not equally available to all persons in need.

Psychosocial support

Psychosocial support remained inadequate in most States Parties. Peer support contributes to fulfilling Dubrovnik Action Plan commitments by providing referrals to existing services, and by enhancing the capacity of national survivors’ organizations and DPOs to deliver relevant services.[44]

In BiH, a project being implemented in 11 municipalities together with the Institute for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation “Dr Miroslav Zotović” in Banja Luka was familiarizing staff of centers for mental health and for physical rehabilitation with the process of integrating peer support during the rehabilitation of mine survivors. The provision of continuing psychosocial support remained weak in Croatia throughout 2017, where there were 21 psychosocial interdisciplinary centers. In Lao PDR, cluster munition victims received psychological support and funeral support for the families of those killed through a survivor-led NGO.

Economic inclusion

The Dubrovnik Action Plan places specific emphasis on increasing the economic inclusion of cluster munition victims through training and employment, as well as social protection measures. While some progress was made in this field, decent work and livelihoods remain the least developed of all victim assistance pillars overall.

Although resources for livelihood and employment remained limited, international organizations, NGOs, and survivors’ organizations increased economic inclusion activities in Albania, Afghanistan, BiH, Lao PDR, and Lebanon in the reporting period. In BiH, the number of such projects doubled, compared to 2016 when the number of beneficiaries had decreased drastically from previous years. In Iraq, the Ministry of Labor did not provide flexible low-interest “soft” loans for conflict survivors as it had in recent years, however, it did provide job opportunities for victims, almost all of whom were women.

Demonstration of Results in Article 7 Transparency Reports

Article 7 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions requires States Parties to report on the status and progress of implementation of victim assistance obligations.

In 2018, Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Chad, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Montenegro, and Mozambique reported on victim assistance efforts, including activities implemented during the previous calendar year. Guinea-Bissau has never submitted an Article 7 report for the Convention on Cluster Munitions, while Sierra Leone did not include the form on victim assistance in its initial Article 7 report, which was the last report submitted. As of 1 August 2018, Somalia had not submitted an initial transparency report, which was due on 31 August 2016.

The Dubrovnik Action Plan recommends that States Parties provide Article 7 reporting updates on victim assistance “drawing on reports submitted under the CRPD as appropriate.” However, the CRPD’s Article 35 reporting has not been used by states thus far to enhance annual Convention on Cluster Munitions reporting. Alternative CRPD reports prepared by civil society are a recognized source of information under the CRPD, and thus could also be an important source for states reporting to the Convention on Cluster Munitions. The Monitor draws information and action points from such so-called “shadow” reporting. A CMC-member DPO, headed by a survivor, completed an alternative CRPD report for Iraq in 2018.

[1] See, Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5 and Article 7(k).

[2] These activities, to be implemented in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law, include medical care, rehabilitation, and psychological support, as well as provision for social and economic inclusion.

[3] ICRC, “ICRC Assistance for the victims of cluster munitions: The perspective of the International Committee of the Red Cross,” presented by Louis Maresca, Legal Adviser, ICRC, November 2007.

[4] Mine Ban Treaty, Article 6.3.

[5] Diplomatic Conference for the Adoption of a Convention on Cluster Munitions, Dublin, 19–30 May 2008, Presidency Text transmitted to the Plenary on Victim Assistance (CCM/PT/12), 23 May 2008, bit.ly/CCM23May2008.

[6] The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons contains only the obligation of assistance, without the implementation provisions found in the Convention on Cluster Munitions. “Each State Party shall, with respect to individuals under its jurisdiction who are affected by the use or testing of nuclear weapons, in accordance with applicable international humanitarian and human rights law, adequately provide age- and gender-sensitive assistance, without discrimination, including medical care, rehabilitation and psychological support, as well as provide for their social and economic inclusion.” Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, Article 6.1 (not yet entered into force), http://undocs.org/A/CONF.229/2017/8.

[7] Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, “Safe Schools Declaration and Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict,” www.protectingeducation.org/safeschoolsdeclaration.

[8] CMC, Cluster Munition Monitor 2016 (Geneva: ICBL-CMC, August 2016), “Casualties and Victim Assistance” chapter, bit.ly/CMM16Casualties-VA.

[9] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.1. Applicable international human rights law and humanitarian law includes the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Protocol V on Explosive Remnants of War, and the Geneva Conventions.

[10] The 95 states are: Afghanistan, Albania, Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Canada, Cape Verde, Chile, Colombia, Comoros, Republic of the Congo, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Cote d'Ivoire, Croatia, Cuba, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Fiji, France, Germany, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Lao PDR, Lesotho, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia FYR, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Malta, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Mozambique, Nauru, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Niger, Norway, Palau, Palestine, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Portugal, Rwanda, Saint Vincent and Grenadines, Samoa, San Marino, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Sweden, Switzerland, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, United Kingdom, Uruguay, and Zambia.

[11] Including Cameroon, in addition to Chad and Lebanon noted above.

[12] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1(d).

[13] Examples of existing groups or individuals whose benefits might be removed include, for example: veterans; civilian war victims who have specific coverage; deminers; those covered by other workers’ rights in the case of an accident. Also, in many countries specific groups of persons with disabilities receive distinct benefits in part due to their advocacy efforts, including the blind and visually impaired, amputees, paralyzed persons, and others.

[14] The preamble states: “Bearing in mind the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which, inter alia, requires that States Parties to that Convention undertake to ensure and promote the full realisation of all human rights and fundamental freedoms of all persons with disabilities without discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability.”

[15] The Monitor provided information to the CRPD committee’s Call for input into General Comment 6 in 2017.

[16] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “General Comment No 6. Article 5: Equality and non-discrimination,” CRPD/C/GC/6, 9 March 2018, para. 43, bit.ly/CRPDCommGenComments.

[17] “Guidance on an Integrated Approach to Victim Assistance: By States for States,” 2016, bit.ly/VAIntegratedApproach. See also, Convention on Cluster Munitions Implementation Support Unit (ISU), “New Guidance on an Integrated Approach to Victim Assistance,” 30 November 2016, bit.ly/CCMISUNewApproach16.

[18] Convention on Cluster Munitions Coordinators of the Working Group on Victim Assistance and the Coordinators of the Working Group on Cooperation and Assistance, “Guidance on an integrated approach to victim assistance,” CCM/MSP/2016/WP.2, 11 July 2016, p. 2, bit.ly/IntegratedApproachGuidance2016.

[19] Ibid.

[20] See, Monitor website, “Victim Assistance Resources,” bit.ly/MonitorVictimAssistance.

[21] Article 5 of the convention requires that States Parties with victims make “every effort to collect reliable relevant data” and assess the needs of cluster munition victims.

[22] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1, bit.ly/DubrovnikActionPlan4-1.

[23] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1(c). A comprehensive coordination mechanism actively involves cluster munition victims and their representative organizations, as well as relevant health, rehabilitation, psychological, and psychosocial services, and education, employment, gender, and disability rights experts.

[24] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1(c).

[25] Dubrovnik Action Plan 4.2, “Increase the involvement of victims,” items (a) and (b). States Parties have obligations to “closely consult with and actively involve cluster munition victims and their representative organizations.” Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.2(f).

[26] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “General comment on article 4.3 and 33.3 of the convention on the participation with persons with disabilities in the implementation and monitoring of the Convention” (* Distr.: DRAFT Restricted), 16 March 2018, bit.ly/CRPDCommGenComments.

[27] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “General Comment No 6. Article 5: Equality and non-discrimination,” CRPD/C/GC/6, 9 March 2018, para. 33, bit.ly/CRPDCommGenComments.

[28] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1(a).

[29] Convention on Cluster Munitions, Article 5.1, which applies with respect to cluster munition victims in areas under the State Party’s jurisdiction or control.

[30] Children require specific and more frequent assistance than adults. Women and girls often need specific services depending on their personal and cultural circumstances. Women face multiple forms of discrimination, as survivors themselves or as those who survive the loss of family members, often the husband and head of household.

[31] Relevant services include medical care, rehabilitation, psychological support, education, and economic and social inclusion. See also, Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1(b).

[32] Article 6.7. “Each State Party in a position to do so shall provide assistance for the implementation of the obligations referred to in Article 5 of this Convention.”

[33] Landmine Survivors Network, “Commentary on the Draft Cluster Munitions Convention,” 12 February 2008.

[34] Krista Orama, Associate Human Rights Officer-Human Rights and Disability, OHCHR, “Integrating disability into international cooperation: the UNPRPD,” Technical Workshop Victim Assistance, Convention on Cluster Munitions Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 15 April 2013, bit.ly/Intersessional2013-TWCooperationAssistance.

[35] UNPRPD Disability Fund, “UNPRPD Mozambique UN Partnership, Mozambique End of Project Report Phase I,” 13 April 2018, http://mptf.undp.org/document/download/19386.

[36] UNPRPD Disability Fund, “UNPRPD Tajikistan UN Partnership, ID 00092306,” 8 December 2017, mptf.undp.org/factsheet/project/00092306.

[37] In a humanitarian response, clusters are groups of humanitarian organizations, both UN and non-UN, in each of the main sectors of humanitarian action. They are designated by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee and have clear responsibilities for coordination. The WHO is the Cluster Lead Agency of the Global Health Cluster.

[38] Active Health Cluster/Sectors exist in 27 countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Myanmar, Niger, Nigeria, Palestine, Pakistan, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine, and Yemen. See, WHO, “Health Cluster: Health Clusters in Countries,” undated, www.who.int/health-cluster/countries/en.

[39] Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), “Introduction to Humanitarian Action a Brief Guide for Resident Coordinators,” October 2015, p. 9.

[40] Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), “IASC Task Team on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action,” undated, bit.ly/IASC-IncludingPersonsWithDisabilities.

[41] “Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action,” undated but 2016, humanitariandisabilitycharter.org.

[42] WHO, “Rehabilitation 2030 Initiative and Call for Action: Priority Activities of the WHO Secretariat 2018–2020,” Stakeholder Consultation Meeting Report, Geneva, Switzerland 11–12 January 2018, received by email from Jody-Anne Mills, Technical Officer Disability and Rehabilitation, WHO, 28 March 2018.

[43] WHO, “Rehabilitation 2030: A Call for Action,” 6–7 February 2017, www.who.int/disabilities/care/rehab-2030/en.

[44] Dubrovnik Action Plan, Action 4.1(b) and 4.2(c).