Landmine Monitor 2019

Banning Antipersonnel Mines

Over the past 20 years, the Mine Ban Treaty has developed into an international norm with impressive universality. A total of 164 States Parties are implementing the treaty’s provisions, which prohibit antipersonnel landmines use, production, trade, or stockpiling and require victim assistance, clearance of mined areas within 10 years, and destruction of stockpiled mines within four years. Most of the 33 countries that remain outside of the treaty abide nonetheless by its key provisions. The stigma against antipersonnel landmines remains strong.

During this reporting period, Landmine Monitor documented new use of antipersonnel mines by government forces in only one country, Myanmar, a state not party to the Mine Ban Treaty.

Non-state armed groups (NSAGs) used antipersonnel mines, particularly improvised mines, with a frequency and scale in recent years that is resulting in a palpable increase in new mine casualties and threatening progress toward the long-held goal of a landmine-free world.[1] NSAGs used antipersonnel mines in at least six countries during this reporting period, including in States Parties Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Yemen, and states not party India, Myanmar, and Pakistan.

In general, States Parties’ implementation of and compliance with the Mine Ban Treaty has been excellent. The core obligations have largely been respected, and when ambiguities have arisen they have been dealt with in a satisfactory manner. However, some States Parties are not doing nearly enough to implement key provisions of the treaty, particularly mine clearance and victim assistance, as detailed in the relevant chapters of this report, or within the online country profiles.

Like-minded governments, United Nations (UN) agencies, and international organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) continue to work together with the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) to address Mine Ban Treaty compliance challenges in a cooperative manner. The unity demonstrated by this community over the past two decades remains strong and focused on the treaty’s ultimate objective of putting an end to the suffering and casualties caused by antipersonnel mines.

Use of Antipersonnel Landmines

There have been no allegations of use of antipersonnel mines by States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty in the reporting period, from mid-2018 through October 2019. However, Landmine Monitor documented new use of antipersonnel mines by government forces in state not party Myanmar. Previously, Landmine Monitor 2018 found that government forces in Myanmar used antipersonnel mines, and Landmine Monitor 2017 found that government forces in states not party Myanmar and Syria used antipersonnel mines.

Landmine Monitor identified new use of antipersonnel landmines by NSAGs in six countries in the reporting period, as listed in the table.

Landmine Monitor has not documented or confirmed, during this reporting period, any use of antipersonnel mines by Syrian government or Russian forces participating in joint military operations in Syria. NSAGs likely continued to use improvised landmines to defend their positions against attack as in previous years, but access by independent sources to territory under NSAG control made it difficult to confirm new use.

Landmine Monitor was also unable to document or confirm allegations of new antipersonnel mine use by NSAGs in Cameroon, Colombia, Mali, Libya, Philippines, Somalia, or Tunisia. However, in many cases, a lack of available information, or means to verify it, meant that it was not possible to determine if mine incidents and casualties were the result of new use of antipersonnel mines, due to legacy contamination of mines laid in previous years, or involved some other kind of explosive device.[3]

Landmine use by government forces

Myanmar

Since the publication of its first annual report in 1999, Landmine Monitor has every year documented the use of antipersonnel mines by government forces, known as the Tatmadaw, and by various NSAGs in Myanmar.

At the treaty’s Seventeenth Meeting of States Parties in November 2018, the Myanmar government representative claimed that allegations that it had used landmines on the border with Bangladesh were without merit, and that joint patrols with Bangladeshi border patrols encountered no mines.[4]

However, in July 2019, an official at the Union Minister Office for Defence stated to Landmine Monitor that “since the start of the civilian era, the Tatmadaw no longer use landmines” but qualified that by stating that in some instances landmines are still used. Specifically, he said,

“In border areas, if the number of Tatmadaw is small, they will lay mines around where they reside, but only if their numbers are small. Mines are also laid around infrastructure such as microwave towers. If these are near villages we warn them. If there is a Tatmadaw camp in an area controlled by an ethnic armed group where they are sniped at and harassed, they will lay mines around the camp.”[5]

Previously, in September 2016, Deputy Minister of Defence Major General Myint Nwe informed the Myanmar parliament that the army continues to use landmines in the internal armed conflict.[6]

Since mid-2018, fighting between the Tatmadaw and NSAG the Arakan Army in Rakhine state has intensified. The Arakan Army has regularly published photographs online of antipersonnel mines produced by the Ka Pa Sa, the state-owned military industries, including MM2, MM5, and MM6 antipersonnel mines among other seized weaponry.[7] While these photographs do not specifically identify new landmine use, they do indicate that antipersonnel mines are part of the weaponry of frontline units.

New landmine casualties in areas of conflict between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army not previously known to have landmine contamination also indicate new use, by either the Arakan Army, the Tatmadaw, or both. In January 2018, Indian authorities blamed landmine casualties occurring on its border with Myanmar, in Mizoram state, on either the Tatmadaw or the Arakan Army, both of whom were operating in the area.[8]

Other claims of new mine use by government forces during the reporting period include:

- In September 2018, Tatmadaw forces allegedly emplaced antipersonnel mines near the villages of Zi Kahtawng and Hka La around Nam San Yang District of Waingmaw township and banned people from going to and from the villages.[9]

- In August 2018, in Muse District, northern Shan state, Tatmadaw allegedly warned the population of Kawng Sahti that they had laid mines around Dung Aw and Uraw Hkyet.[10]

- In July 2018, in Waingmaw township of Kachin state, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) alleged that the Tatmadaw was emplacing antipersonnel mines along the Nam Sang River and antivehicle mines on the Zi Kahtawng road.[11]

Frequently it is difficult to ascribe specific responsibility for an incident to a particular combatant group. In August 2019, in northern Shan state, the Tatmadaw engaged in armed conflict with three members of the Northern Alliance—the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Arakan Army—near Maw Harn village in Kutkai township. Subsequently, a Maw Harn villager was injured by a landmine. The villagers said there had been no landmines in the area prior to the conflict, but do not know whether government forces, NSAGs, or both, were responsible.[12] In September 2019, near Nama Dar village in Paletwa township of Chin state, two villagers were injured by a landmine following armed conflict between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army at that spot. The villagers were unsure which entity laid the mine.[13]

In June 2018, the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar reported, following their investigations into mine use allegations in September 2017, that it had

“reasonable grounds to conclude that landmines were planted by the Tatmadaw, both in the border regions as well as in northern Rakhine state, as part of the ‘clearance operations’ with the intended or foreseeable effect of injuring or killing Rohingya civilians fleeing to Bangladesh. Further, it seems likely that new antipersonnel mines were placed in border areas as part of a deliberate and planned strategy of dissuading Rohingya refugees from attempting to return to Myanmar.”[14]

In June 2018, the 20th Battalion of the KIA shared photographs with Landmine Monitor that it said showed mines that its forces cleared from the villages of Gauri Bum, Man Htu Bum, and Uloi Bai in Danai township. The photographs show around 80 antipersonnel mines, all M14 and MM2 types, with markings indicating Myanmar manufacture. The KIA alleged that Tatmadaw forces laid these mines in April and May, when the government forces left villages after occupying them. The KIA stated that two of their soldiers were injured while clearing the mines.[15]

Landmine Monitor subsequently showed the photographs to an official at the Myanmar Ministry of Defence in June 2018 and requested comment. The official noted that one mine shown in a photograph was an antivehicle mine and said that government forces do not use antivehicle mines against the insurgents as the NSAGs do not use vehicles. He said that the antipersonnel mines could be copies of Myanmar-made mines that a NSAG planted, as he said the Myanmar army does not leave landmines behind after an operation.[16]

Landmine use by NSAGs

In the reporting period, Landmine Monitor identified new use of antipersonnel mines by NSAGs in Afghanistan, India, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Yemen.

Afghanistan

NSAG use of improvised mines in Afghanistan in 2018 and 2019 resulted in numerous casualties.[17] The use of improvised mines in Afghanistan is mainly attributed to the Taliban, Haqqani Network, and Islamic State forces. According to the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), “anti-government” forces used victim-activated improvised mines in slightly decreasing numbers throughout 2018 and the first half of 2019.[18]

India

Maoist insurgents have made sporadic use of improvised landmines. In April 2019, an indigenous person was reportedly killed by an improvised pressure mine, allegedly laid by the Communist Party of India-Maoist (CPI-M).[19] In January 2018, a wild elephant was injured by a landmine in the Latehar district, Jharkhand state, allegedly laid by the CPI-M.[20] Previously, in July 2017, the Deputy Inspector General of Police in Chhatisgarh state told the state news agency, “Pressure IEDs planted randomly inside the forests in unpredictable places, where frequent de-mining operations are not feasible, remain a challenge.”[21]

Myanmar

Many NSAGs have used antipersonnel mines in Myanmar since 1999. In late 2018 and early 2019, there were reports of new use by the KIA, Arakan Army, Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA), Karen National Defense Organization (KNDO), and the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA).[22] Frequently it is difficult to ascribe specific responsibility for an incident to a particular combatant group. For example, in August 2019, in northern Shan state, the Tatmadaw engaged in armed conflict with three members of the Northern Alliance—the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Arakan Army—near Maw Harn village in Kutkai township. Subsequently a resident of Maw Harn village was injured by a landmine. The villagers said there had been no landmines in the area prior to the conflict, but do not know which group was responsible.[23]

In February and March 2019, in Manli village in Namtu township of Shan state, several villagers were killed and injured by mines when returning to their agricultural fields after fighting between the Shan State Army-South and an alliance of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army and the Shan State Army-North.[24] In April 2019, the Office of the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services accused the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and Shan State Progressive Party (SSPP) of laying the mines that caused the injuries.[25] In September 2019, near Nama Dar village in Paletwa township of Chin state, two villagers were injured by a landmine following fighting between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army. The villagers were unsure which group laid the mine.[26] In February 2019, near Nam Maw Lon village, in Hsipaw township, in northern Shan state, a villager died and two were injured after stepping on a mine in an area that had seen recent fighting between the Restoration Council Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA) and the Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North (SSPP/SSA). Both groups blamed the other side for the incident.[27]

Most allegations of new use were reported in Kayin, Rakhine, and Shan states:

- In July 2019, in Hpapun township of Kayin state, the KNDO laid mines in the Bu Ah Der village tract reportedly to defend against attack by Tatmadaw.[28]

- In May 2019, in Hlaingbwe township of Kayin state, a DKBA officer from Meh Pru village tract ordered his soldiers to plant more landmines in seven nearby mountainous villages to protect the area.[29]

- In December 2018, the Pa-O National Liberation Organization of southern Shan state stated that the Restoration Council Shan State/Shan State Army-South had frequently laid landmines in their area.[30]

- In August–September 2018, in Hpapun township of Kayin state, KNLA Battalion #102, Company #4 informed villagers that they would lay mines near former Tatmadaw military camps, and that they should not go to those areas. Subsequently two Tatmadaw soldiers reportedly were injured by these mines.[31]

- In November 2018, two civilians were injured in a mine incident which the KIA blamed on use by the TNLA.[32]

- In October 2018, New Mon State Party claimed that the KNU had laid landmines in a disputed area in Yebyu township in Thanintharyi region.[33] The KNU denied the allegation.[34]

- In August 2018, near Kammamaung in Hlaingbwe township of Kayin state a KNLA soldier was injured by a mine he had laid.[35]

Nigeria

In Nigeria, the NSAG Boko Haram has used improvised landmines since mid-2014.[36] In June 2019, Nigeria reported new contamination in the northeastern part of the country.[37] Previously in September 2018, Mines Advisory Group (MAG) issued a report detailing significant new use of improvised antipersonnel landmines by Boko Haram and its splinter groups on roads, in fields, and in villages, mostly in Borno state, but also in Yobe and Adamawa states.[38]

In June 2019, the Nigerian Army published photographs of two pressure plate activated explosive devices encountered during counter insurgency activities in Borno state.[39] Previously, on 6 March 2018, four loggers were killed when they stepped on landmines reportedly laid by Boko Haram near Dikwa, 90 kilometers east of Maiduguri in Borno state, after they went to retrieve a vehicle abandoned the previous day during a Boko Haram attack.[40] In early 2017, UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) reported extensive use of improvised mines by Boko Haram in northern areas of Nigeria.[41]

Pakistan

NSAGs in Balochistan and Khyber Paktunkhwa used improvised antipersonnel landmines during the reporting period. Use is attributed to a variety of militant groups, frequently referred to as “miscreants” in media reports, but generally accepted to be constituent groups of the Tehrik-i-Taliban in Pakistan (TTP) and Balochi insurgent groups.[42] As in previous years, many military personnel and some civilians were killed or injured in incidents of new use, however from available information it is difficult to make specific attribution to the perpetrators. The Monitor has recorded numerous antipersonnel mine incidents in Balochistan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, although in some cases the precise date of mine use cannot be ascertained.

Yemen

Houthi forces in Yemen used antipersonnel and antivehicle mines during 2018 and 2019, primarily on the west coast of the country near the port of Hodeida. Houthi forces are also reported to have used landmines in the past along the coast, along the border with Saudi Arabia, around key towns, along roads, and to cover retreats.

A Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen convened by the UN Human Rights Council reported in September 2019, “The use of landmines, both anti-personnel and anti-vehicle, by the Houthis has resulted in significant harm to civilians.” According to the report, the group

“investigated reports of civilian casualties caused by anti-personnel and anti-vehicle landmines allegedly emplaced by Houthi fighters in Aden, Al Hudaydah, Lahij and Ta’izz governorates, and examined further reports of civilian casualties from landmines in Abyan, al-Dhale’e, Al-Bayda, Al-Jawf, Hajjah, Ibb, Ma’rib, Sana’a, Sa’dah and Shabwah governorates. It confirmed civilian casualties from anti-personnel landmines verified as having been emplaced by Houthi fighters in incidents it investigated in Aden, Al-Hudaydah, Lahij and Ta’izz governorates.”[43]

In April 2019, Human Rights Watch reported that Houthi-planted landmines had killed at least 140 civilians since 2018.[44] In November 2018, employees at the Hodeidah port accused Houthi forces of placing landmines in the area around the port’s entrances.[45] Previously, the Yemen Mine Action Center (YEMAC) reported that Houthi forces laid more than 300,000 landmines between 2016 and 2018.[46] International media reported that mine clearance teams funded by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) cleared and destroyed hundreds of Houthi-laid mines in 2018.[47]

There is no evidence to suggest that members of the Saudi Arabia-led coalition have used landmines in Yemen.

Universalizing the Landmine Ban

Since the Mine Ban Treaty entered into force on 1 March 1999, states wishing to join can no longer sign and ratify the Treaty but must accede, a process that essentially combines signature and ratification. Of the 164 States Parties, 132 signed and ratified the treaty, while 32 acceded.[48]

No states joined the Mine Ban Treaty in the reporting period.

The 33 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty include the Marshall Islands, which is the last signatory yet to ratify.

Annual UN General Assembly resolution

Since 1997, an annual UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolution has provided states outside the Mine Ban Treaty with an important opportunity to demonstrate their support for the humanitarian rationale of the Treaty and the objective of its universalization. More than a dozen countries have acceded to the Mine Ban Treaty after voting in favor of consecutive UNGA resolutions.[49]

On 5 December 2018, UNGA Resolution 73/61 calling for universalization and full implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty was adopted by a vote of 169 in favor, none against, and 16 abstentions.[50] This is a slight increase in votes in favor from the 2017 resolution (167) and maintains the lowest number of abstentions ever recorded.

A core of 14 states not party have abstained from consecutive Mine Ban Treaty resolutions, most of them since 1997: Cuba, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, Syria, Uzbekistan, the United States (US), and Vietnam.[51]

Non-state armed groups

Some NSAGs have committed to observe the ban on antipersonnel mines, which reflects the strength of the growing international norm and stigmatization of the weapon. None have done so during the reporting period. At least 70 NSAGs committed to halt using antipersonnel mines since 1997.[52] The exact number is difficult to determine, as NSAGs have no permanence, frequently split into factions, go out of existence, or become part of state structures.

In November 2016, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) and the Colombian government signed an agreement to end the armed conflict. This halted the FARC’s widespread improvised landmine use and resulted in the surrender and destruction of its stockpiled mines and components. In August 2019, however, a small contingent of rebel, former FARC, leaders announced that they were entering a “new stage of armed struggle.”[53] It is not yet clear whether that group will continue use of improvised antipersonnel mines. Previously, in October 2017, a ceasefire was agreed between the government of Colombia under which the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN) committed not to use antipersonnel landmines that could endanger the civilian population.[54] However, the ceasefire ended in January 2018, and as of October 2019 had not been renewed.[55]

Production of Antipersonnel Mines

More than 50 states produced antipersonnel mines at some point in the past.[56] Forty-one states have ceased production of antipersonnel mines, including four that are not party to the Mine Ban Treaty: Egypt, Israel, Nepal, and the US.[57]

The Monitor identifies 11 states as producers of antipersonnel mines, unchanged from the previous report: China, Cuba, India, Iran, Myanmar, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, and Vietnam. Most of these countries are not believed to be actively producing mines but have yet to disavow ever doing so.[58]

Those most likely to be actively producing are India, Myanmar, and Pakistan.

In August 2019, South Korea informed the ICBL that it had not produced any antipersonnel landmines in the previous five years.[59] Until its renounces future production, South Korea remains listed as a producer of antipersonnel mines.

Production of antipersonnel mines by India continued in 2018 and orders indicate that production extended into 2019. Purchase order records retrieved from a publicly accessible online government transaction database list private companies providing component parts for APER-1B antipersonnel mines to the Indian Ordnance Factories, a state-owned enterprise, into June 2019.[60] Previously, in September 2018, Indian military officials told the Monitor that the final assembly of complete mine remains under the exclusive control of Indian Ordnance Factories.[61] In the previous two years, components were produced under these contracts and supplied to the Ammunition Factory Khadki in Maharashtra state.[62]

NSAGs have produced improvised landmines in Afghanistan, Colombia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tunisia, and Yemen.[63] In September 2018, the arms consultancy Conflict Armament Research reported that Houthi forces were “mass producing” landmines, including victim-activated IEDs (improvised antipersonnel landmines). It found that this includes the standardization and production of explosive charges, pressure plates, and passive infrared sensors.[64]

Previously, in January 2017, MAG reported that Islamic State in Syria and Iraq produced near-factory quality improvised landmines on a large scale.[65]

Transfers of Antipersonnel Mines

A de facto global ban on the transfer of antipersonnel mines has been in effect since the mid-1990s. This ban is attributable to the mine ban movement and the stigma created by the Mine Ban Treaty. Landmine Monitor has never conclusively documented any state-to-state transfers of antipersonnel mines since it began publishing annually in 1999.

At least nine states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty have enacted formal moratoriums on the export of antipersonnel mines: landmine producers China, India, Pakistan, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, plus Israel, Kazakhstan, and the US. Other past exporters have made statements declaring that they have stopped exporting, including Cuba and Vietnam. Iran also claims to have stopped exporting in 1997, despite evidence to the contrary.[66]

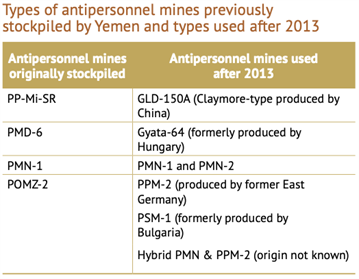

At least five types of antipersonnel mines produced in the 1980s have been used in Yemen since 2013. None of these mines were among the four types of antipersonnel mines that Yemen has reported stockpiling in the past, including for training mine clearance personnel.

The evidence of further use of antipersonnel mines starting in 2016 suggests either that the 2002 declaration to States Parties on the completion of landmine stockpile destruction was incorrect, or that these mines were acquired from another source after 2002. In a September 2016 letter, Yemen’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Sanaa, controlled by the Houthis and the General People’s Congress, alleged that individuals had smuggled weapons, including landmines, into Yemen in recent years, noting that their government had not been able to control its land or sea borders due to instability and fighting.[67] In April 2017, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied that the Sanaa-based Ministry of Defense stockpiles antipersonnel mines.[68]

Stockpiled Antipersonnel Mines

States not party

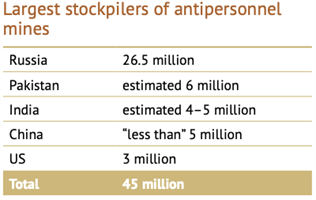

The Monitor estimates that as many as 30 of the 33 states not party to the Mine Ban Treaty stockpile antipersonnel landmines.[69] In 1999, the Monitor estimated that, collectively, states not party stockpiled about 160 million antipersonnel mines, but today the global collective total may be less than 50 million.[70]

It is unclear if all 30 states are currently stockpiling antipersonnel mines. Officials from the UAE have provided contradictory information regarding its possession of stocks, while Bahrain and Morocco have stated that they have only small stockpiles used solely for training purposes in clearance and detection techniques.

States not party to the Mine Ban Treaty routinely destroy stockpiled antipersonnel mines as an element of ammunition management programs and the phasing out of obsolete munitions. In recent years, such stockpile destruction has been reported in China, Israel, Mongolia, Pakistan, Russia, South Korea, the US, and Vietnam.

Non-state armed group stockpiles

Fewer NSAGs appear to be able to obtain factory-made antipersonnel mines now that production and transfers have largely halted under the Mine Ban Treaty. Some NSAGs in states not party have acquired landmines by stealing them from government stocks, purchasing them from corrupt officials, or removing them from minefields. Most that use mines appear to make their own improvised landmines from locally available materials.

The Monitor largely relies on reports of seizures by government forces, reports of significant use, or verified photographic evidence from journalists to identify NSAGs possessing mine stockpiles.

Stockpile Destruction by Mine Ban Treaty States Parties

At least 160 of the 164 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty do not stockpile antipersonnel mines. This includes 93 states that have officially declared completion of stockpile destruction and 67 states that have declared they never possessed antipersonnel mines (except in some cases for training in detection and clearance techniques).

Collectively, States Parties have destroyed more than 55 million stockpiled antipersonnel mines, including more than 1.4 million destroyed in 2018.

Three States Parties possess more than a combined four million antipersonnel mines remaining to be destroyed: Ukraine (3.5 million), Greece (643,267), and Sri Lanka (77,865). It is unclear if State Party Tuvalu possess stocks of antipersonnel landmines.[71] Somalia clarified in its annual transparency report that it does not possess stocks.

In November 2018, Oman announced the completion of destruction of its stockpiles ahead of its 1 February 2019 deadline.[72] It began the destruction process on 13 September 2015 and completed destruction on 25 September 2018. Oman destroyed 6,104 antipersonnel mines in 2018.[73]

Sri Lanka declared a significant stockpile of antipersonnel mines in November 2018 when it submitted its initial transparency measures report. Its deadline for completion of destruction is 1 June 2029, but Sri Lanka stated its intent to complete stockpile destruction by the end of 2020.[74] Sri Lanka reported that the destruction of 57,033 antipersonnel mines had occurred prior to November 2018, for a total stockpile prior to destruction of 134,898 antipersonnel mines.

Greece and Ukraine remain in violation of Article 4 after failing to complete the destruction of their stockpiles by their four-year deadline.[75] Neither state has indicated when the obligation to destroy its remaining stockpiles will be completed. The Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014 called on States Parties that missed their deadline to comply without delay, and also to communicate their plans to do so, to request any assistance needed, and to provide an expected completion date. The Maputo Action Plan added a call for these states to provide a plan for the destruction of their remaining stockpiles by 31 December 2014.

Destruction of stockpiles by NSAGs

Disarmament of the FARC in Colombia, including destruction of its antipersonnel landmine stockpile and components, occurred under UN supervision and was completed on 22 September 2017. The UN mission destroyed 3,528 antipersonnel mines formerly belonging to the FARC, as well as components, including more than 38,000kgs of explosives and more than 46,000 detonators.[76]

From 2006 to 2019, Polisario Front of Western Sahara undertook eight public destruction events in order to totally destroy its stockpile of antipersonnel mines, pursuant to the Geneva Call Deed of Commitment. On 6 January 2019, with an eighth and final destruction of 2,485 stockpiled antipersonnel mines, it destroyed the last of its stockpiled mines, which once totaled 20,493.[77]

Mines Retained for Training and Research (Article 3)

Article 3 of the Mine Ban Treaty allows a State Party to retain or transfer “a number of anti-personnel mines for the development of and training in mine detection, mine clearance, or mine destruction techniques…The amount of such mines shall not exceed the minimum number absolutely necessary for the above-mentioned purposes.”

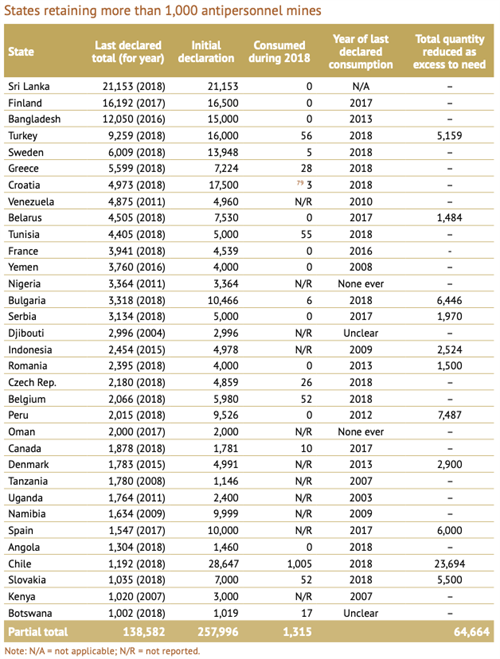

A total of 69 States Parties have reported that they retain antipersonnel mines for training and research purposes, of which 33 retain more than 1,000 mines and three (Sri Lanka, Finland, and Bangladesh) each retain more than 12,000 mines. Ninety-six States Parties have declared that they do not retain any antipersonnel mines, including 37 states that stockpiled antipersonnel mines in the past.[78]

In addition to those listed above, another 34 States Parties each retain fewer than 1,000 mines and together possess a total of 14,842 retained mines.[80]

In May 2019, Thailand announced it had carried out a review of its retained mines and would destroy a further 3000 before the end of 2019.[81] However, at an event on 6 August 2019, Thailand destroyed its entire number of retained mines of 3,133, at which Thai Armed Forces Joint Chief of Staff General Chaichana Nakkerd stated “From now on, Thailand will no longer retain any more anti-personnel landmines.”[82]

While laudable for transparency, several States Parties are still reporting as retained antipersonnel mines devices that are fuzeless, inert, rendered free from explosives, or otherwise irrevocably rendered incapable of functioning as an antipersonnel mine, including by the destruction of the fuzes. Technically, these are no longer considered antipersonnel mines as defined by the Mine Ban Treaty; a total of at least 13 States Parties retain antipersonnel mines in this condition.[83]

The ICBL has expressed concern at the large number of States Parties that are retaining mines but apparently not using those mines for permitted purposes. For these States Parties, the number of mines retained remains the same each year, indicating none are being consumed (destroyed) during training or research activities. No other details have been provided about how the mines are being used. A total of eight States Parties have never reported consuming any mines retained for permitted purposes since the treaty entered into force for them: Burundi, Cape Verde, Cyprus, Djibouti, Nigeria, Oman, Senegal, and Togo.

Transparency Reporting

Article 7 of the Mine Ban Treaty requires that each State Party “report to the Secretary General of the United Nations as soon as practicable, and in any event not later than 180 days after the entry into force of this Convention for that State Party” regarding steps taken to implement the treaty. Thereafter, States Parties are obligated to report annually, by 30 April, on the preceding calendar year.

Only one State Party has an outstanding deadline for submitting its initial report: Tuvalu (due 28 August 2012).

As of 1 October 2019, 49% of States Parties had submitted annual reports for calendar year 2018. A total of 83 States Parties have not submitted a report for calendar year 2018. Of this latter group, most have failed to submit an annual transparency report for two or more years.[84]

Nigeria, Yemen, and other states with recent allegations or confirmed reports of use of improvised landmines by NSAGs have failed to provide information on new contamination in their annually updated Article 7 reports.

Morocco, a state not party, submitted a voluntary report in 2017–2019 (as well as in 2006, 2008–2011, and 2013). In previous years, Azerbaijan (2008 and 2009), Lao PDR (2010), Mongolia (2007), Palestine (2012 and 2013), and Sri Lanka (2005) submitted voluntary reports.

[1] The Mine Ban Treaty defines an antipersonnel landmine as “a mine designed to be exploded by the presence, proximity or contact of a person and that will incapacitate, injure or kill one or more persons.” Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) or booby-traps that are victim-activated fall under this definition regardless of how they were manufactured. The Monitor frequently uses the term “improvised landmine” to refer to victim-activated IEDs.

[2] NSAGs used mines in at least eight countries in 2017–2018, nine countries in 2016–2017, 10 countries in 2015–2016 and 2014–2015, seven countries in 2013–2014, eight countries in 2012–2013, six countries in 2011–2012, four countries in 2010, six countries in 2009, seven countries in 2008, and nine countries in 2007. In the reporting period, there were also reports of NSAG use of antivehicle mines in Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Iraq, Kenya, Lebanon, Mali, Niger, Pakistan, Philippines, Somalia, Syria, Tunisia, Ukraine, and Yemen.

[3] New use resulting in casualties is confirmed to have occurred in 2017 earlier than October in Iraq and Syria, and was suspected earlier than October 2017 in Cameroon and Saudi Arabia, as reported in Landmine Monitor 2017. These findings are listed in Landmine Monitor 2017.

[4] Statement of Myanmar, Mine Ban Treaty Seventeenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 30 November 2018, http://bit.ly/MyanmarMSP2018. “[T]he security forces of Myanmar and Bangladesh have been conducting coordinated patrol along the border in the west of Myanmar. Coordinated patrol has been made for 19 times so far since August of this year. No incidents of landmines casualty have been reported in the area. Such accusation without concrete evidence will not help facilitate countries to join the convention.”

[5] Landmine Monitor meeting with U Min Htike Hein, Assistant Secretary, Union Minister Office for Defence, Ministry of Defence, in Naypyitaw, 5 July 2019.

[6] “Pyithu Hluttaw hears answers to questions by relevant ministries,” Global New Light of Myanmar, 13 September 2016, www.burmalibrary.org/docs23/GNLM2016-09-13-red.pdf. The deputy minister stated that the Tatmadaw used landmines to protect state-owned factories, bridges, and power towers, and its outposts in military operations. The deputy minister also stated that landmines were removed when the military abandoned outposts, or warning signs were placed where landmines were planted and soldiers were not present.

[7] See, Mine Free Myanmar, “Allegedly Seized Mines Displayed by Arakan Army,” 18 April 2019, https://burmamineban.demilitarization.net/?p=906.

[8] “Man hurt in Mizoram IED blast,” The Telegraph, 18 January 2018, http://bit.ly/2MShazs.

[9] “FBR: Clash Summary: Chaos Reigned in Northern Shan State in September,” Free Burma Rangers, 15 October 2018.

[10] “FBR: Clash Summary: Battles Continue in Northern Shan State Throughout August,” Free Burma Rangers, 12 September 2018.

[11] “FBR: Burma Army Tortures and Kills Six Female Medics, Continues Campaign Against Civilians,” Free Burma Rangers, 26 July 2018.

[12] “Kutkai Villager ‘Seriously Injured’ by Landmine,” Burma News International, 20 September 2019, www.bnionline.net/en/news/kutkai-villager-seriously-injured-landmine.

[13] Thein Zaw, “Two villagers injured by a landmine explosion in Paletwa,” Narinjara News, 9 September 2019, http://bit.ly/NN992019.

[14] Human Rights Council, “Report of the detailed findings of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar,” A/HRC/39/CRP.2, 17 September 2018, p. 288, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/A_HRC_39_CRP.2.pdf.

[15] Thein Zaw, “Two villagers injured by a landmine explosion in Paletwa,” Narinjara News, 9 September 2019, http://bit.ly/NN992019.

[16] Human Rights Council, “Report of the detailed findings of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar,” A/HRC/39/CRP.2, 17 September 2018, p. 288, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/A_HRC_39_CRP.2.pdf.

[17] In June 2018, Afghanistan stated that that new use of improvised mines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) were responsible for killing approximately 171 civilians every month. Statement of Afghanistan, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 8 June 2018, bit.ly/AfgISM18.

[18] UNAMA, “Afghanistan: Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict Annual Report 2018,” Kabul, February 2019, p. 24, http://bit.ly/2BMQedT; UNAMA, “Afghanistan: Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict Annual Report 2017,” Kabul, February 2017, p. 31, bit.ly/AfgUNAMA2017; and UNAMA, “Afghanistan: Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict mid-year report 2018,” Kabul, July 2018, p. 5, http://bit.ly/2pgvWqA.

[19] “One civilian killed in landmine blast,” Hans News Service, 1 April 2019, http://bit.ly/THNI517256.

[20] “Hurt tusker hints at rebels,” The Telegraph, 15 January 2018, http://bit.ly/2pXzg9W.

[21] Tikeshwar Patel, “IEDs pose huge challenge in efforts to counter Naxals: police,” Press Trust of India, 24 July 2017, http://bit.ly/2WfK8vY.

[22] There are also allegations of use by the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), the Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army-North (SSPP/SSA) and the Restoration Council Shan State/Shan State Army-South (RCSS/SSA) in their operations against Myanmar armed forces during the reporting period.

[23] “Kutkai Villager ‘Seriously Injured’ by Landmine,” Burma News International, 20 September 2019, www.bnionline.net/en/news/kutkai-villager-seriously-injured-landmine.

[24] Myat Moe Thu, “Three killed, four injured by landmine in Shan State,” Myanmar Times, 1 April 2019, www.mmtimes.com/news/three-killed-four-injured-landmine-shan-state.html.

[25] Min Naing Soe, “Army announces TNLA and SSPP planned mine attack in Manli Village,” Eleven Myanmar, 1 April 2019, http://bit.ly/2WgbbY6.

[26] Thein Zaw, “Two villagers injured by a landmine explosion in Paletwa,” Narinjara News, 9 September 2019, http://bit.ly/NN992019.

[27] “One Killed, Two Injured in Hsipaw Landmine Blast,” Burma News International, 20 February 2019, www.bnionline.net/en/news/one-killed-two-injured-hsipaw-landmine-blast.

[28] Karen Human Rights Group, “KHRG Submission to Landmine Monitor,” September 2019, unpublished.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Nyein Nyein, “Shan Armed Group Kills At Least Four Ethnic Pa-O in Shooting,” the Irrawaddy, 12 December 2018, www.irrawaddy.com/news/shan-armed-group-kills-least-four-ethnic-pa-o-shooting.html.

[31] Karen Human Rights Group, “KHRG Submission to Landmine Monitor,” September 2019, unpublished.

[32] “FBR: Clash Summary: Steady Fighting in November in Northern Burma,” Free Burma Rangers, 15 December 2018.

[33] “Landmine blasts injure two in NMSP-KNU disputed-area in Yebyu Tsp within this month,” Burma News International, 29 October 2018, http://bit.ly/349sMnt.

[34] “Three More Landmines Explode in Tanintharyi,” Burma News International, 9 January 2019, www.bnionline.net/en/news/three-more-landmines-explode-tanintharyi.

[35] “Skirmishes Between Burma Army and KNLA Increase in Northern Karen State,” Karen News, 18 September 2018, http://bit.ly/31PMEKH.

[36] See, ICBL-CMC, “Country Profile: Nigeria: Mine Ban Policy,” 2015–2018, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2019/nigeria/mine-ban-policy.aspx.

[37] Statement of Nigeria, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Session on Stockpile Destruction, 22 May 2019, http://bit.ly/346kJaK.

[38] MAG, “Out of Sight: Landmines and the Crisis in Northeast Nigeria,” September 2018, p. 4, bit.ly/MAGNigeria2018. MAG states that their research revealed that almost 90% of victims of explosive incidents were from antipersonnel landmines, with a casualty rate of almost 19 per day during 2017 and early 2018.

[39] It is uncertain from available information if this device can be triggered by a person. Nigerian Army, “Troops thwart terrorist ambush,” Press Release, 23 June 2019, http://bit.ly/369HZql.

[40] “Boko Haram terror continues, 10 killed in fresh attacks,” Telangana Today (AFP), 7 March 2018, https://telanganatoday.com/boko-haram-kills-nigerian-attacks.

[41] UNMAS, “Mission Report: UNMAS Explosive Threat Scoping Mission to Nigeria, 3 to 14 April 2017,” p. 2.

[42] Email from Raza Shah Khan, Sustainable Peace and Development Organization (SPADO), 30 September 2019, and 21 September 2017. See also, “Landmine blasts kill five in Pakistan’s tribal areas,” Arab News (Pakistan), 21 August 2019, www.arabnews.pk/node/1543081/pakistan; “Soldier martyred, 5 injured in North Waziristan landmine blast,” Tribal News Network, 25 August 2019, www.tnn.com.pk/soldier-martyred-5-injured-in-north-waziristan-landmine-blast/; “At least 2 FC personnel killed, 5 injured in Kurram Agency blast,” The Nation, 10 July 2017, http://bit.ly/32RwQsf; and Ajmal Wesai, “4 children wounded in Tirinkot bomb explosion,” Pajhwok Afghan News, 5 August 2017, www.pajhwok.com/en/2017/08/05/4-children-wounded-tirinkot-bomb-explosion.

[43] “Situation of human rights in Yemen, including violations and abuses since September 2014: Report of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts as submitted to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights,” A/HRC/42/17, 9 August 2019, para. 45, http://bit.ly/2JpVUPg.

[44] “Yemen: Houthi Landmines Kill Civilians, Block Aid,” Human Rights Watch, 22 April 2019, www.hrw.org/news/2019/04/22/yemen-houthi-landmines-kill-civilians-block-aid.

[45] “Houthis mine Hodeidah port entrances as pro-government offensive pauses,” Middle East Eye, 14 November 2018, http://bit.ly/2qQhndX.

[46] Conflict Armament Research, “Mines and IEDs Employed by Houthi Forces on Yemen’s West Coast,” September 2018, p. 4, http://bit.ly/32PfuMp.

[47] See for example, @LostWeapons, “another couple weeks, another thousand mines cleared in yemen. TM62 anti tank mines, press plates, cylinder IEDs,” 12 October 2018, Tweet, https://twitter.com/LostWeapons/status/1050646259185242112/photo/1; and @BrowneGareth, “UAE soldiers prepare a cache of Houthi landmines and IEDs for a controlled explosion near Mokha today #Yemen #hodeidah #Aden #IEDS,” 17 July 2018, Tweet, https://twitter.com/BrowneGareth/status/1019296299391373312/photo/1.

[48] The 32 accessions include two countries that joined the Mine Ban Treaty through the process of “succession.” These two countries are Montenegro (after the dissolution of Serbia and Montenegro) and South Sudan (after it became independent from Sudan). Of the 132 signatories, 44 ratified on or before entry into force (1 March 1999) and 88 ratified afterward.

[49] This includes: Belarus, Bhutan, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Estonia, Finland, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Oman, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka, and Turkey.

[50] The 16 states that abstained were: Cuba, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Myanmar, Nepal, North Korea, Pakistan, Palau, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Syria, the US, and Vietnam.

[51] Uzbekistan voted in favor of the UNGA resolution on the Mine Ban Treaty in 1997.

[52] As of October 2019, 46 through the Geneva Call Deed of Commitment, 20 by self-declaration, four by the Rebel Declaration (two signed both the Rebel Declaration and the Deed of Commitment), and two through a Peace Accord (Nepal, Colombia). See, Geneva Call, “Deed of Commitment,” undated, www.genevacall.org/how-we-work/deed-of-commitment/.

[53] Megan Janetsky, “Ex-FARC leaders’ return to arms brings back memories of bloodshed,” Al Jazeera, 30 August 2019, http://bit.ly/32QcwYh.

[54] See, “Acuerdo y comunicado sobre el cese al fuego bilateral y temporal entre el Gobierno y el ELN (Agreement and communiqué on the bilateral and temporary ceasefire between the Government and the ELN),” Oficina del alto comisionando para la paz, Quito, 4 September 2017, bit.ly/AcuerdoELN2017.

[55] Adriaan Alsima, “Colombia’s ELN rebels blame government for failure to agree to ceasefire,” Colombia Reports, 2 July 2018, http://bit.ly/31PzjSv.

[56] There are 51 confirmed current and past producers. Not included in that total are five States Parties that some sources have cited as past producers, but who deny it: Croatia, Nicaragua, Philippines, Thailand, and Venezuela. It is also unclear if Syria has produced antipersonnel mines.

[57] Additionally, Taiwan passed legislation banning production in June 2006. The 36 States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty that once produced antipersonnel mines are Albania, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iraq, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Uganda, the United Kingdom (UK), and Zimbabwe.

[58] For example, Singapore’s only known producer of antipersonnel landmines, ST Engineering, a government-linked corporation, said in November 2015 that it “is now no longer in the business of designing, producing and selling of anti-personnel mines.” Local Authority Pension Fund, “ST Engineering Quits Cluster Munitions,” 18 November 2015, http://bit.ly/2p5nz17. However, Singapore is still listed as a producer as it has not formally committed to not produce landmines in the future.

[59] Email to the ICBL, from Soonhee Choi, Counsellor, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Korea, 22 August 2019.

[60] In February 2018, Supreme Industries Ltd was listed as having concluded a contract for production of material for antipersonnel mines on the Indian Ordnance Factories Purchase Orders, http://ofbindia.gov.in/index.php?wh=purchaseorders&lang=en. However, no other orders were listed as concluded between December 2017 and September 2018 for antipersonnel mines. Components and materials for directional mines and antivehicle mines were listed.

[61] Landmine Monitor meeting with Cdre. Nishant Kumar, Ministry of External Affairs, and Col. Sumit Kabthiyal, Ministry of Defense, Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Group of Governmental Experts (GGE), Geneva, 27 August 2018.

[62] The following companies were listed as having concluded contracts listed for production of components of antipersonnel mines on the Indian Ordnance Factories Purchase Orders between October 2016 and November 2017: Sheth & Co., Supreme Industries Ltd., Pratap Brothers, Brahm Steel Industries, M/s Lords Vanjya Pvt. Ltd., Sandeep Metalkraft Pvt Ltd., Milan Steel, Prakash Machine Tools, Sewa Enterprises, Naveen Tools Mfg. Co. Pvt. Ltd., Shyam Udyog, and Dhruv Containers Pvt. Ltd. In addition, the following companies had established contracts for the manufacture of mine components: Ashoka Industries, Alcast, Nityanand Udyog Pvt. Ltd., Miltech Industries, Asha Industries, and Sneh Engineering Works. Mine types indicated were either M-16, M-14, APERS 1B, or “APM” mines, http://ofbindia.gov.in/index.php?wh=purchaseorders&lang=en. Indian Ordnance Factories website, http://ofb.gov.in/vendor/general_reports/show/registered_vendors/820.

[63] Previous lists of NSAGs producing antipersonnel mines have included Iraq, Syria, and Thailand. However, with the loss of territory by Islamic State, it was not possible to confirm that this activity continued in the reporting period.

[64] Conflict Armament Research, “Mines and IEDs Employed by Houthi Forces on Yemen’s West Coast,” September 2018, http://bit.ly/32PfuMp.

[65] MAG Issue Brief, “Landmine Emergency: Twenty years on from the Ottawa Treaty the world is facing a new humanitarian crisis,” January 2017.

[66] Landmine Monitor received information in 2002–2004 that demining organizations in Afghanistan were clearing and destroying many hundreds of Iranian YM-I and YM-I-B antipersonnel mines, date stamped 1999 and 2000, from abandoned Northern Alliance frontlines. Information provided to Landmine Monitor and the ICBL by HALO Trust, Danish Demining Group, and other demining groups in Afghanistan. Iranian antipersonnel and antivehicle mines were also part of a shipment seized by Israel in January 2002 off the coast of the Gaza Strip.

[67] Letter from Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Yemen, to Human Rights Watch, 7 September 2016, bit.ly/YemenHRWSept2016.

[68] Ibid., 2 April 2017, bit.ly/YemenLetterApr2017HRW.

[69] Three states not party, all in the Pacific, have said that they do not stockpile antipersonnel mines: Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Tonga.

[70] In 2014, China informed Landmine Monitor that its stockpile is “less than” five million, but there is an amount of uncertainty about the method China uses to derive this figure. For example, it is not known whether antipersonnel mines contained in remotely-delivered systems, so-called “scatterable” mines, are counted individually or as just the container, which can hold numerous individual mines. Previously, China was estimated to have 110 million antipersonnel mines in its stockpile.

[71] Tuvalu has not made an official declaration, but is not thought to possess antipersonnel mines. Somalia acknowledged that “large stocks are in the hands of former militias and private individuals,” and that it is “putting forth efforts to verify if in fact it holds antipersonnel mines in its stockpile.” No stockpiled mines have been destroyed since the treaty came into force for Somalia, which had a destruction deadline of 1 October 2016. It has not provided an annual update to its transparency report since 2014. Tuvalu, Mine Ban Treaty Initial Article 7 Report (for the period 16 April 2012 to 30 March 2013), Sections B, E, and G, bit.ly/MBTSomalia2013Art7.

[72] Statement of Oman, Mine Ban Treaty Seventeenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 29 November 2018, http://bit.ly/OmanMSP2018. Oman reiterated this information in its Article 7 transparency report submitted in 2019.

[73] Oman, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (in Arabic), submitted April 2019, states that in 2018 Oman destroyed 502 No. 7 dingbat mines; 4,624 M409 mines; and 978 DM 31 mines, http://bit.ly/OmanArt72019.

[74] Sri Lanka, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form B, November 2018, http://bit.ly/SriLankaArt72018.

[75] Greece had a deadline of 1 March 2008, while Ukraine had a deadline of 1 June 2010.

[76] “Misión de la ONU concluyó hoy la inhabilitación de armas de las Farc,” Radio Nacional de Colombia, 22 September 2017, http://bit.ly/2BNpjia.

[77] Geneva Call, “Final destruction of 2,485 stockpiled anti-personnel mines in Western Sahara,” Press Release, 22 January 2019, http://bit.ly/2Nk2YhH.

[78] In 2018, Cambodia, Argentina, and Ethiopia destroyed the entirety of their stockpile retained for training and research, and the UK announced that their stockpile was comprised of inert munitions that do not fall under the scope of the convention. Tuvalu has not submitted an initial transparency report, which was originally due in 2012.

[79] Croatia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form D, 30 April 2019, http://bit.ly/2WhJ7DA. There is a discrepancy in Croatia’s reporting on its retained mines. The 2019 report lists 4,973 mines retained for training and research, a decrease of 77 from the number reported in 2018 (5,050). However, Croatia lists only three mines as consumed in 2018 in accordance with Article 3—one each of type PMA-1A, PMA-2, and PMR-2A.

[80] Zambia (907), Mali (900), Mozambique (900), Japan (898), Netherlands (889), BiH (834), Honduras (826), Sudan (739), Mauritania (728), Cambodia (720), Portugal (694), Italy (617), South Africa (576), Germany (465), Zimbabwe (450), Cyprus (440), Togo (436), Nicaragua (435), Brazil (364), Congo (322), Cote d’Ivoire (290), Slovenia (272), Uruguay (260), Bhutan (211), Cape Verde (120), Eritrea (101), Gambia (100), Jordan (100), Ecuador (90), Rwanda (65), Senegal (50), Benin (30), Guinea-Bissau (9), and Burundi (4).

[81] Statement of Thailand (written submission), Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Session on Article 3, Geneva, 24 May 2019, http://bit.ly/ThaiMBTIM2019.

[82] Thanaporn Promyanyai, “Thai army destroys thousands of landmines in jungle,” AFP, 6 August 2019, https://yhoo.it/3435yzd.

[83] Afghanistan, Australia, BiH, Canada, Eritrea, France, Gambia, Germany, Lithuania, Mozambique, Senegal, Serbia, and the UK.

[84] States that have not submitted reports for two or more years are noted in italics: Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belize, Benin, Bhutan, Brunei Darussalam, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Comoros, Congo (Rep. of), Côte d’Ivoire, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, Dominica, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Fiji, Finland, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Grenada, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Iceland, Indonesia, Jamaica, Kenya, Kiribati, Kuwait, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Malta, Mauritius, Monaco, Namibia, Nauru, Nigeria, Niger, Niue, North Macedonia, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Philippines, Rwanda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and Grenadines, Samoa, São Tomé & Príncipe, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Spain, Suriname, Tanzania, Timor-Leste, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, Uruguay, Vanuatu, and Venezuela.