Landmine Monitor 2019

Victim Assistance

The Mine Ban Treaty and Victim Assistance

This overview concerns the status of victim assistance, with a focus on 2018 and 2019 as relevant. It encompasses a summary of achievements attained as well as the challenges faced, by and in, States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty with significant numbers of mine/explosive remnants of war (ERW) victims in need of assistance.[1] In particular, it is an opportunity to weigh up the state of victim assistance in the context of the completion of the treaty’s Maputo Action Plan (2014–2019), with a view to the implementation of the next five-year Oslo Action Plan, to be adopted at the Mine Ban Treaty Fourth Review Conference in 2019.

The Mine Ban Treaty is the first disarmament or humanitarian law treaty through which States Parties committed to provide assistance for those people harmed by a specific type of weapon.[2] The ICBL pushed vigorously to have language related to assistance to mine victims included in the treaty’s text. The preamble recognizes the desire of States Parties “to do their utmost in providing assistance for the care and rehabilitation, including the social and economic reintegration of mine victims…” Article 6 of the treaty requires that each State Party “in a position to do so” to provide such assistance. Article 6 also affirms the right of each State Party to seek and receive assistance to the extent possible for victims. Since the treaty’s entry into force this has been understood to imply a responsibility of the international community to support victim assistance in mine-affected countries with limited resources.

While the term “landmine survivor” was widely used—including in Landmine Monitor reporting—at the time of the Mine Ban Treaty First Review Conference in Nairobi in 2004, the treaty text has used the legal term “victim.” A definition of “landmine victim” was agreed by States Parties in the Final Report formally adopted in Nairobi as “those who either individually or collectively have suffered physical or psychological injury, economic loss or substantial impairment of their fundamental rights through acts or omissions related to mine utilization.”[3] This widely accepted understanding of who is the focus of assistance also includes family members of casualties, both killed and injured, as well as affected communities.

Self-identification as a “victim” or as a “survivor” is an important element of the choice of use. “Whether someone sees themselves or someone else as a victim or as a survivor can greatly impact their overall sense of self, their quality of life and their reintegration into their community as a productive member of society.”[4] There is also a concern in the disability rights community that use of the word “victim” can reopen the door to discriminatory and belittling approaches to persons with disabilities.

The Monitor has tracked progress in the services, programs, and activities that benefit victims under the Mine Ban Treaty and its subsequent five-year action plans since 1999. Victim assistance aims to reduce the mortality rate of and improve the opportunities for recovery and rehabilitation of people injured by mines/ERW, achieve comprehensive rehabilitation of victims and the full inclusion of victims in wider society, as well as ensuring that the same assistance is available to affected communities.

That assistance includes, but is not limited to, the following components and practices (also referred to as pillars): data collection and needs assessment with referral to emergency and continuing medical care; physical rehabilitation, including prosthetics and other assistive devices; psychological and psychosocial support; social and economic inclusion; and the adoption or adjustment of relevant laws and public policies. Preferably, such assistance is to be provided through a holistic and comprehensive approach comprised of all of the above elements. In addition, though less information is available, some victim assistance efforts are reported that reach family members and other people who have suffered trauma, loss, or other harm due to mines/ERW.

It is evident that tens of thousands of mine/ERW victims, persons with disabilities, and other people with similar needs have benefited from the increased attention given to the issue of victim assistance by States Parties and the international community since the Mine Ban Treaty entered into force in 1999. Numerous programs and projects to enhance the availability accessibility and adequacy of healthcare, physical rehabilitation, and social and economic inclusion have been implemented.

Despite ongoing financial shortages that evidently reduced the availability of some services in recent years, victim assistance efforts have remained, to a large degree, robust, and donors and providers have maintained their determination to increase achievements and improve the survival rate of people injured and the quality of life of survivor and indirect victims. For over two decades the many improved methods and successful activities undertaken, as recorded by the Monitor, have shown that delivering victim assistance is not inherently complicated.

Although many challenges remain in creating access to suitable and enduring services and in covering all pillars of holistic and integrated assistance, Monitor research demonstrates that there is a much better understanding of the needs in affected countries.

Yet, it is also well recognized that many victims have not had access to emergency medical services, comprehensive rehabilitation, or the opportunity to participate in society on an equal basis with others. Some have never had access to facilities and services. Many local and international NGOs have reported decreased funding and resources for most countries and programs in recent years, especially those not in emergency settings. The decline in finances and supplies is limiting existing operations and threatening the sustainability of essential programs. It also reveals that existing services are far from meeting the needs of victims and the disparities are yet to be covered by other frameworks.

The Mine Ban Treaty’s action plans support victim assistance by building on States Parties’ commitments to: save lives; enhance health services; increase physical rehabilitation; develop psychosocial support capacities; actively support socio-economic inclusion; develop and implement relevant policy frameworks; give consideration to cross-cutting factors, including gender, age, and disability; enhance data collection; involve mine victims in the work of the treaty; and ensure the meaningful participation of victims and other relevant experts at international meetings.

In June 2004 at the Mine Ban Treaty First Review Conference in Nairobi, an initial group of 24 States Parties[5] “themselves have indicated there likely are hundreds, thousands or tens-of-thousands of landmine survivors” and that they had the greatest responsibility to act, but also the greatest needs and expectations for assistance. All States Parties committed to the Maputo Action Plan, which included a set of actions that would advance victim assistance through 2019.[6]

Progress during the Nairobi Action Plan (2004–2009) period was most evident in the improved process and planning of assistance, well above that made in the increased availability and implementation of health, rehabilitation, economic, or psychological services. Those States Parties that had made significant advances on their self-defined objectives realized achievements related to data collection, coordination, strategies, and awareness-raising.

At the beginning of the Cartagena Action Plan period (2009–2014), service provision remained inadequate and had not increased significantly nor had life conditions of most survivors, though data indicates that the survival rate of people injured improved in that time. Thus, many victims received some form of assistance through the years, while facing too many gaps in services and implementation of assistance that was largely unsystematic and unsustainable. Most efforts remained focused on medical care and physical rehabilitation, often supported by international organizations and funding. Furthermore, the steps actually made in increasing programs and activities that directly benefited victims, while beneficial, were often unrelated to the specific objectives of the strategies that those countries had developed for themselves in order to fulfill the commitments of the Nairobi Action Plan.

The Roadmap for Victim Assistance 2014–2019: The Maputo Action Plan

At the start of the Maputo Action Plan period, approximately two-thirds of States Parties had active coordination mechanisms and relevant national plans in place.

In most of these countries, victim assistance efforts have collaborative coordination, combined planning, and/or victim participation. Victims participated in decisions that affect their lives and in the implementation of services in nearly all the relevant States Parties. Yet, in many countries, victim participation required additional support, especially for victims to be effectively included in coordination roles.

The Maputo Action Plan highlights the continued relevance of the actions of the Cartagena Action Plan, issues a strong call for effective victim participation, and underscores the importance of integrating victim assistance into other frameworks. The plan’s seven victim assistance-related action points set an agreed path for States Parties to continue working to address the needs of victims with targeted and mainstream actions across a range of ministries and stakeholders and to raise the issue of mine victims in “international, regional and national human rights, healthcare, labour and other fora, instruments and domains” while continuing to report “measurable achievements” in victim assistance at international meetings of the Mine Ban Treaty.

Relevant action points of the Maputo Action Plan may be summarized as follows:

- Assess the needs of mine victims. Assess the availability and gaps in services. Support efforts to refer victims to existing services.

- Communicate time-bound and measurable objectives.

- Enhance plans, policies, and legal frameworks.

- Strengthen local capacities, enhance coordination, and increase the availability of and accessibility to services, opportunities, and social protection measures.

- Enhance the capacity and ensure the inclusion and full and active participation of mine victims and their representative organizations in all matters that affect them.

- Raise awareness of the imperative to address the needs and to guarantee the rights of mine victims.

- Report on measurable improvements.

The Maputo Action Plan called on States Parties to undertake actions to address victim assistance “with the same precision and intensity as for other aims of the Convention.”

The Committee on Victim Assistance replaced the Standing Committee on Victim Assistance and Socio-Economic Reintegration and was given a new mandate, for the first time specifically directing the committee to take the discussion of the needs and rights of victims to other relevant forums, while continuing to provide advice for States Parties efforts to advance in their victim assistance commitments.

Victim assistance, disability rights, and other frameworks

Since the emergence of victim assistance through the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, other weapons-related conventions have adopted this rapidly emerging norm. The 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions codified the expanded principles and commitments of victim assistance into binding international law; these were introduced into the planning of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) Protocol V on ERW in 2008, and most recently included in the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

At the Mine Ban Treaty First Meeting of States Parties in Maputo in 1999, the international mine action community first articulated the notion that victim assistance is to be a part of broader contexts, including human rights approaches.[7] Subsequently, in the Mine Ban Treaty’s first Action Plan adopted in 2004, States Parties committed to ensuring that they effectively address the “fundamental human rights of mine victims” through national legal and policy frameworks.[8]

The 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is legally binding, providing an overarching mechanism for the amendment of national laws and policies related to persons with disabilities. The CRPD does not provide for new rights but it frames the existing rights catalogue in an accessible way. The CRPD pertains also to victims of indiscriminate weapons.Although not all injuries result in long-term physical impairment, the impact of indiscriminate weapons frequently results in landmine and ERW survivors becoming persons with disabilities and therefore protected by the CRPD.

Similarly, over time it has become more widely recognized that, just as efforts to respond to the needs of victims should benefit all persons with similar needs, including other persons with disabilities, without discrimination, so should the rights of victims be considered by disability rights actors.This interconnectivity allows for solution-oriented approaches to implementing international legal commitments and legal obligations that arise from the CRPD, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and the Mine Ban Treaty.

Global conferences, symposia, and regional meetings raised awareness of good practices and concrete actions, services, and policies that can, in coordination with others, positively alter the lives of victims. Chief among those were the “Bridges between Worlds,” meetings in 2014 including a main global conference held in Colombia that discussed assistance to victims of mines/ERW in broader contexts of disarmament, human rights, and development efforts, particularly disability rights.[9] In September 2019, a three-day Global Conference on Assistance to Victims of Anti-Personnel Mines and Other Explosive Remnants of War and Disability Rights, chaired by Prince Mired Raad Zeid Al-Hussein of Jordan took place in Amman.[10]

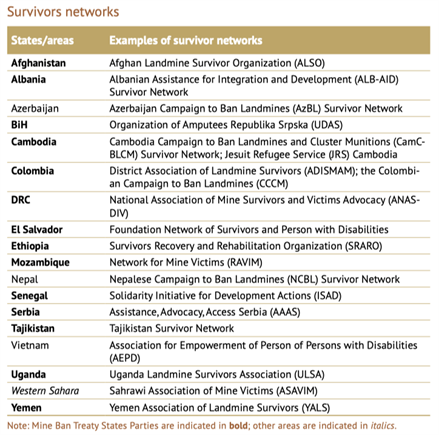

In 2009, national survivor networks previously existing as country programs of the United States-based NGO Survivor Corps (or Landmine Survivors Network, LSN) transitioned to become nationally registered organizations in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), El Salvador, Ethiopia, and Vietnam, among others. Subsequently, from 2012–2015, the ICBL-CMC’s Survivor Networks Project, supported by Norway, provided resources to campaign member networks (including former LSN country branches) and trained representatives of survivor networks and disabled person’s organizations (DPOs) on monitoring the Mine Ban Treaty, the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and the CRPD as a means to promote the rights of victims and persons with disabilities. Victim assistance NGOs, survivor networks, and DPOs in many countries made efforts to collaborate with each other and with development and rights actors to promote the inclusion of mine/ERW victims and persons with disabilities in mainstream programs and in policy-making bodies at national and local levels.

Since the adoption of the Maputo Action Plan, substantial progress was also made by civil society organizations forging links across sectors and regions to advance the rights of mine/ERW victims and other persons with similar needs. In 2014, for example, Humanity & Inclusion (then-Handicap International), in collaboration with the ICBL-CMC, convened a Latin American seminar in Colombia on psychosocial assistance for victims of armed conflict, including mine/ERW victims and persons with disabilities. This became an annual event, bringing together representatives of networks of mine/ERW victims, networks of armed conflict survivors, DPOs, and service providers. The fifth Latin American Regional Seminar for Strengthening the Network of Landmine and ERW Survivors and Persons with Disabilities hosted by Humanity & Inclusion with ICBL-CMC participation was held in Bogota in August 2019, in the lead up to the Mine Ban Treaty Fourth Review Conference. Topics included strengthening assistance networks, accessing rights, and monitoring human rights.

In September 2015, UN Member States adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They are designed to address the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development, with an emphasis on poverty reduction, equality, rule of law, and inclusion. Therefore, the SDGs are generally complementary to the aims of the Mine Ban Treaty, the CRPD and the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and offer exceptional opportunities for bridging the relevant frameworks.

More specifically, persons with disabilities are referred to directly in several of the SDGs that are highly relevant to the implementation of the CRPD and the humanitarian disarmament conventions’ action plans: education (SDG 4), employment (SDG 8), reducing inequality (SDG 10), and accessibility of human settlements (Goal 11), in addition to including persons with disabilities in data collection and monitoring (SDG 17).

Mine Ban Treaty victim assistance continues to be an essential commitment for victims especially in conflict-affected, post-conflict, and fragile states. These same states have limited capacity, as reflected in the lack of regular reporting to the Mine Ban Treaty, that would help the international community determine how best to earmark assistance. In many of these states, the provision of victim assistance can both benefit from, and contribute to, the implementation of the SDGs. Victim assistance supports the needs of many other people affected by conflict, particularly those impacted by other types of explosive weapons. It is clear that a significant commitment to sustained international cooperation is needed to assist states in meeting their victim assistance obligations.

Those states with existing capacity and services tend to get the most attention and are also most often used as examples of good practices. Yet, many of these states face circumstances that limit their opportunities to report on the progress that they have made, hindering their ability to identify needs and to request appropriate assistance. With support, states facing such challenges can make greater progress, but not if they are overlooked and their challenges remain unheard.

Victim assistance and the Oslo Action Plan[11]

The draft Oslo Action Plan confirms the States Parties’ continuing commitment to “ensuring the full, equal and effective participation of mine victims in society, based on respect for human rights, gender equality and non-discrimination.” It also reaffirms States Parties understanding that “victim assistance should be integrated into broader national policies, plans and legal frameworks relating to the rights of persons with disabilities, and to health, education, employment, development and poverty reduction in support of the realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals.”[12]

Proposed victim assistance-relevant actions include activities to implement the following:

- Ensure the meaningful participation of mine victims in all related matters and meetings.[13]

- A government entity for coordination.[14]

- Inter-governmental planning, national policies, and legal frameworks.[15]

- A centralized database on victims’ needs and challenges.[16]

- Timely first aid response and pre-hospital care.[17]

- A national referral mechanism and directory of services.[18]

- Comprehensive healthcare, rehabilitation support services, and psychological and psychosocial support services.[19]

- Social and economic inclusion.[20]

- Protection in situations of risk, including situations of armed conflict, humanitarian emergencies, and natural disasters.[21]

Participation of victims and their representative organizations[22]

Victims were reported to be included through representation in coordination in Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand. As yet States Parties have rarely reported on the outcomes of victim participation, and how their input is considered or acted upon. In some states, victims’ representative organizations and other service providers involved in coordination and planning reported that the concerns and contributions of victims were not genuinely taken into account, despite their attendance at relevant meetings.

Relevant government agency to coordinate victim assistance[23]

Of the 33 States Parties, 21 had active victim assistance coordination linked with disability coordination mechanisms that considered the issues relating to the needs of mine/ERW victims. The states with coordination mechanisms in 2018–2019 were: Afghanistan, Angola Albania, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Croatia, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), El Salvador, Ethiopia, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, and Turkey. Angola’s coordination mechanism is not interconnected with disability rights coordination.

Inter-governmental planning, national policies and legal frameworks[24]

Adopting, and implementing, a comprehensive inter-ministerial plan of action that identifies gaps and aims to fulfill the rights and needs of victims and, or among, other persons with disabilities, is a key step to ensuring a coordinated response to the needs.

Albania, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Jordan, Mozambique, Peru, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Thailand have a current plan that addresses national victim assistance activities and Zimbabwe has a set of measurable objectives.

Afghanistan, Algeria, Burundi, Cambodia, Croatia, Senegal, South Sudan, Uganda, and Yemen need to revise, finalize, or adopt a draft and implement, their national disability plan, policy, or strategy that includes objectives that respond to the needs of victims and recognizes its victim assistance obligations and commitments, together with a monitoring structure. Mozambique still has to implement the Action Plan for Assistance to Victims through relevant government departments and ministries.

States Parties that need to develop a plan or strategy include DRC, Eritrea, Guinea-Bissau, Nicaragua, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, and Turkey. In the meantime, DRC requires a sustainable planning and coordination mechanism working at national and local levels to increase efforts to implement the victim assistance objectives of its national mine action strategy. Turkey, which now has coordination, must develop a plan for implementation of victim assistance. Newer States Parties, Palestine, and Sri Lanka are yet to create a strategic framework for victim assistance.

Centralized database with needs and challenges[25]

States Parties commit to assess the needs of victims. This commitment includes assessing the availability and gaps in services and support, and existing or new requirement activities needed to meet the needs of victims in the frameworks of disability, health, education, employment, development, and poverty reduction. Assessment also provides an initial opportunity to refer victims to existing services.

Few structured national needs assessment surveys were conducted since 2015. Mine Action Centers and service providers often collected information on victims in an ongoing manner in conjunction with other victim assistance and program activities.

Some notable survey activities and assessments of needs of survivors since 2015 included the following:

Afghanistan’s National Disability Database initiated in 2017 was under development and planned to be installed by the end of 2019. Statistics on persons with disabilities and the families of those killed could be used to coordinate with the ministry of finance, pension department, and population registration department to provide the necessary services. In Albania, an assessment of socio-economic and medical needs of marginalized ERW victims carried out during 2013–2016 was completed. In Cambodia, village-level quality of life assessments for victims and other persons with disabilities continued into 2019. Data collection on the needs of mine/ERW victims was ongoing in Colombia and new data management systems were put in use during the period.

Croatia made early progress in the development of a unified database on the needs of mine/ERW victims, specifically including families, which stalled from 2017 onward. In Serbia, the ministry responsible for victim assistance worked with other government institutions to improve coordination on data and needs assessment. In Tajikistan, the International Committee of the Red Cross/Crescent (ICRC) carried out needs assessment from which information was entered into the national database to be shared with relevant stakeholders. Thailand reported that data collection on mine/ERW victims was relatively advanced and that survivors are included in disability assessments. In Yemen, more mine/ERW victims were registered with the mine action center through ongoing survey conducted jointly with the national survivor association until increased conflict disrupted regular assessment and data collection.

Algeria needed to ensure that all victims are registered and therefore able to receive pensions and other benefits and to develop a central data collection mechanism on victims needs to improve planning of victim assistance. BiH needed to review its existing data and speed up the establishment of a mine/ERW victims database in Republika Srpska. Burundi needed to develop a national database on victims and needs. Chad has yet to improve and systematize casualty data collection. Croatia needed to complete the national victim survey and unified victim database in process since 2015. Eritrea needed to develop a mechanism to document, record, and share information on mine/ERW accidents. Iraq needed to establish a unified and coordinated system of data collection and analysis for survivors and other persons with disabilities. Mine action actors in Somalia were alerted to the need for collecting appropriate data from a situation assessment of the victim assistance sector. And Yemen needed to improve the collection of data and create a usable database of victims’ needs.

Disability survey, including through national census questions, was proposed in many national and international contexts. CRPD Article 31 calls on States Parties to collect information, including statistical and research data, and to disaggregate this information to identify barriers faced by persons with disabilities in exercising their rights. Action #35 of the draft Oslo Action Planincludes each relevant state having a centralized database that includes information on mine victims and needs and challenges, disaggregated by gender, age, and disability.

Timely first aid response for casualties and adequate pre-hospital trauma care[26]

Time-sensitive emergency care includes interventions such as first aid and field trauma response, emergency evacuation, availability of transport, and immediate medical care that involves assessment and prehospital communication of critical information for patient handover. The provision of appropriate emergency medical services can considerably affect the chance of the survival and the speed of recovery of mine victims, as well as outcomes of injuries and the severity of impairments.

Improvements in medical care services to strengthen emergency response capacities for people injured by mines/ERW and others in affected communities were reported in Afghanistan and Croatia.

In Guinea-Bissau, only the hospital in the capital city can treat serious injuries. There is a drastic problem of accessibility of immediate healthcare across the DRC where in most cases people injured cannot receive appropriate assistance, resulting in death. In South Sudan, incidents often occurred in remote areas far from access to health services.

International organizations continued to provide much needed assistance in conflict-affected areas. Healthcare services for all persons with disabilities in Iraq decreased over time, in part due to the recent security situation. In Yemen, healthcare deteriorated, many medical facilities were damaged, and ongoing conflict further undermined the struggling health system. In Ukraine, along the line of contact, primary‑healthcare centers and satellite services received required equipment and medicines.

National referral mechanisms[27]

States Parties can improve accessibility of services by ensuring that existing data collection, needs assessment, and service providers have the capacity to make referrals to appropriate health and rehabilitation facilities. Similarly, taking a holistic approach to assistance, health, and rehabilitation service providers can provide referrals to others who can support the inclusion of victims. Referral mechanisms can involve at the national level mechanisms as well as local community referrals network, including through community-based rehabilitation systems.

Since 2015, national governmental bodies providing referrals included a range of both mine action centers and government ministries, such as: Algeria’s Ministry of National Solidarity, Family and the Status of Women; Angola’s Ministry of Assistance and Social Reintegration; the Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority’s data department CMVIS; the Colombian Department for Comprehensive Action Against Antipersonnel Mines (DAICMA) and the broader government run reparations program at the Victim’s Unit; the Rehabilitation and Integration Division within Eritrea’s Ministry of Labour and Human Welfare; Iraq’s Directorate for Mine Action; the Tajikistan Mine Action Center; and the Yemen Mine Action Center.

However, many more non-governmental groups and organizations provided referrals at a national or local level in the States Parties with victims, including a range of survivor networks, national NGOs and DPOs, and international NGOs, notably Humanity & Inclusion, as well as the ICRC and national Red Cross and Red Crescent movements.

Rehabilitation, healthcare, psychosocial support[28]

In many countries, including Cambodia, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mozambique, Somalia, South Sudan, and Somalia, a lack of available and accessible medical care may have a significant impact on the quality of life of victims. Many affected countries continue to report inadequate numbers of trained staff, health services, and other treatments such as pain management, in remote, rural, and other mine-affected areas.

Several countries saw improved healthcare infrastructure in affected areas ensuring that facilities have adequate equipment, supplies, and medicines necessary to meet basic standards.

Rehabilitation including physiotherapy and the supply of assistive devices such as prostheses, orthoses, mobility aids, and wheelchairs help the person regain or improve mobility and to engage in everyday activities. Psychosocial support is often an integral aspect of rehabilitation. Rehabilitation services with a comprehensive or multidisciplinary approach involve a team including a medical doctor, physiotherapist, prosthetist, and social worker as well as other specialists as needed. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Article 12.1. recognizes the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. Article 15.1.(b) of that convention recognizes the right of everyone to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications. This can also apply to prosthetic and assistive devices.

States can increase the sustainability of rehabilitation by allocating a specific budget line for physical and functional rehabilitation needs of all persons with disabilities including victims. In Algeria, victims and persons with disabilities continued to have access to most prosthetic and assistive devices free-of-charge. Additional rehabilitation facilities were built in Iraq in 2018–2019, including a much-needed new center in Mosul, but the entire rehabilitation system lacked capacity to deliver enough services and devices to meet the increased needs.

In Afghanistan, authorities have acknowledged that it would be unrealistic to consider the government capable of ensuring the required rehabilitation services. New physical rehabilitation centers were established in three provinces of Afghanistan, however at least seven more centers were still needed. A record number of Afghan citizens with disabilities sought rehabilitation services in 2018. Afghanistan reported that 90% of the population lives more than 100km away from a rehabilitation center and 20 of the 34 provinces do not have a prosthetics center. Access to rehabilitation centers is also extremely limited in Uganda, South Sudan, and Mozambique.

In Cambodia, slow progress was made in the handover of rehabilitation centers to government management while securing resources for their sustainability. In BiH and Serbia, where orthopedic are state regulated, excessive and unnecessary bureaucratic procedures limited access to devices. Iraq developed a multi-sector rehabilitation strategy and Palestine adopted an emergency rehabilitation plan.

A much-needed new rehabilitation center was launched in Mosul, Iraq in 2018, however the entire rehabilitation sector required increased resources and capacity. In Palestine, the main prosthetic center in Gaza faced significant strain on its limited resources while addressing an increase in patients with amputations among protesters who had been shot in the legs. In part to meet this demand, a new prosthetic hospital and disability rehabilitation center was opened in 2019. Accessing materials and financial resources were an obstacle to rehabilitation in Sri Lanka, where most prostheses were available through charities. In Yemen, increased support to the physical rehabilitation sector was reported in response to the needs caused by ongoing conflict, but availability of assistance overall remained far from adequate for meeting those needs.

Outreach programs including mobile clinics improved access to physical rehabilitation services in affected communities, often offering both repair and replacement of devices. Access to physiotherapy care was extended through home visits in El Salvador. In Nicaragua, the health ministry hired additional technicians for satellite centers and the national rehabilitation center. Since 2015, mine/ERW victims from Senegal have been receiving prosthetic devices in Guinea-Bissau through an agreement between the ICRC, the Senegalese Survivor Network, and the mine action center.

Despite this being the pillar of victim assistance that has seen the greatest focus, many outstanding essential activities remained to be fulfilled for States Parties in the field of rehabilitation, for example: in Afghanistan there was a need to expand access to physical rehabilitation needs, particularly in provinces lacking services or where traveling to receive rehabilitation is difficult for victims; in Albania to develop existing capacities and management of the prosthetic center in Tirana and increase financial resources; in Angola to adequately support the prosthetic and orthopedic centers, including provision of materials; in BiH to improve the quality and sustainability of services, including by upgrading community-based rehabilitation centers; and in Burundi to improve access to physical rehabilitation for victims by eliminating fees for services.

It remained necessary for Cambodia to improve sustainability of the entire physical rehabilitation sector; for Chad to increase investment in physical rehabilitation services; for DRC to improve the availability of physical rehabilitation and psychosocial services significantly throughout the country; for Eritrea to mobilize resources to expand the community-based rehabilitation program; for Ethiopia to establish a national supply chain of rehabilitation materials; for Turkey to make adequate prosthetic and rehabilitation facilities a priority in the mine-affected regions; for Sri Lanka to coordinate rehabilitation and insure adequate supplies; and for Uganda to improve the sustainability, quality, and availability of prosthesis and rehabilitation services, including by enhancing coordination and dedicating the necessary national resources to what is currently considered a non-funded priority.

Psychological and psychosocial support activities include professional counselling, individual peer-to-peer counselling, community-based peer support groups, networks of survivors and associations of persons with disabilities, as well as some types of sports and recreation activities.

In BiH, there was a program to develop structured peer-to-peer psychological support, by victims for victims, in healthcare and rehabilitation facilities, however such initiatives remained rare. In Senegal, victims supported other victims who received assistance in Guinea-Bissau. Survivor networks, which often provide peer-to-peer and collective psychosocial support, struggled to maintain their operations with decreasing resources available. Mine/ERW victims in Kinshasa hold monthly peer-support meetings.

Many countries had improved sport and recreational activities for persons with disabilities, including families, such as wheelchair sports. However, access to cultural activities for victims and persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others was often lacking.

The following are some of the needs for psychological and psychosocial support identified: in Afghanistan, to provide psychosocial and psychological support, including peer support, in particular to new victims as well as those who have been traumatized and live in isolation; in Cambodia to improve the quality and availability psychological support services; in Colombia to include peer support services under the health insurance system; in DRC to improve the availability of psychosocial services significantly, especially outside the capital; in Mozambique to prioritize assistance based on psychological and socioeconomic needs; in Nicaragua to dedicate resources to implementation of psychosocial support programs; and in Senegal to ensure the sustainability of psychosocial support in the Casamance region.

Social and economic inclusion[29]

Most frequently NGOs or charity institutions implemented socio-economic inclusion projects for victims through education, sports, leisure and cultural activities, vocational training, micro-credit, income generation, and employment. However, there are exceptions, in Serbia, for example, the priority of the Ministry of Labour, Employment, Veteran and Social Affairs was the social inclusion of veterans, veterans with disabilities, civilian invalids of war, and families of military war casualties. Thus, the state supported the development of veteran and disability protection services, social protection services, and employment in remote and rural areas.

Action #39 of the draft Oslo Action Plan includes “efforts to ensure the social and economic inclusion of mine victims” through access to education and capacity-building.

Economic inclusion was a reported priority need in all states, and particularly in Cambodia Ethiopia, Nicaragua, Senegal, South Sudan, Thailand, and Uganda where employment, work training, livelihood incentives, and other economic opportunities continued to be areas with the greatest need for improvement for victims. There was a recognized need to increase economic opportunities for survivors and other persons with disabilities and develop education and training that are appropriate for victims and persons with disabilities who lack education and literacy and have no work or land from which to make a living.

A lack of awareness of disability rights and inclusion principles among teachers and fellow pupils can lead to discrimination, isolation, and prevent child victims from participating fully in educational activities. For example, it was reported that in Somalia the majority of children with disabilities did not get accepted at schools as pupils.

National programs to promote inclusive education at all levels, as part of the national education plans, policies and programs can contribute to the inclusion of child survivors and indirect child victims. In Afghanistan, an inclusive education policy was drafted, translated into national languages, and shared with the Ministry of Education for review and approval by its scientific and academic council. However, government-run national inclusive education program that increased the enrollment of children with disabilities in the country since 2008 lost core international funding from victim assistance sources in 2016, but through 2018 was implemented in part by NGO stakeholders. In DRC, one NGO conducted local inclusive education awareness-raising activities. But for another that also has remedial teaching schools in the east of the country for children of mine casualties, funding was insufficient for the school year in 2018–2019.

Gender-sensitive, age-appropriate, and disability inclusive victim assistance

Action #39 of the Draft Oslo Action Plan calls for the “removal of physical, social, cultural, political, attitudinal and communication barriers in a gender-sensitive, age-appropriate and disability inclusive manner.”

Children, especially boys, are one of the largest groups of survivors. Since child survivors have specific and additional needs in all aspects of support, age- and disability-appropriate assistance is required.[30]

Following are some examples of related activities and challenges.

In Yemen, where the UN Development Programme (UNDP) reported that women, children, the elderly, and persons with disabilities are at greater risk of losing access to health services. UNICEF expanded its victim assistance services to children amputees in 2018 through support to two prosthesis and rehabilitation centers in Aden and Taizz governorates that provided the children with prosthesis and artificial limbs. Most of the children were mines/ERW survivors.

In BiH, survivors received support in setting up income-generating activities, including children and widows of people killed by mines/ERW.

In Afghanistan, the inclusive and child-friendly education coordination meetings focused on inclusion of the children who do not have access to education, in particular, children with disabilities. The action plan of the Technical Subcommittee of Assistance to Victims in Colombia included identification of child and adolescent survivors in order to provide opportunities for inclusive education within the framework of a 2017 decree, which regulates inclusive education for all persons with disabilities.

In Guinea-Bissau, the ICRC funded education for children with disabilities and installed ramps in front of school. In Turkey, it was reported that a large number of school-age children with disabilities did not receive adequate access to education. In Iraq, many children with disabilities dropped out of public school due to insufficient physical access to school buildings. Issues preventing children with disabilities attending school include a lack of transport, a lack of assistive devices, physical barriers, teachers without appropriate training, and the need for children to help with housework.

In Mozambique, UNICEF and Humanity & Inclusion together reach children with disabilities with Information, Orientation, and Social Support Service mobile teams, which identify children with disabilities and provide services, including assistive devices and physical modifications to enable school attendance. In Zimbabwe, men, women, and children have received prosthetics from the collaboration between a prosthetics center and mine action operators HALO Trust and NPA, despite there being no specific programs or activities targeting women or children survivors.

While men and boys are the majority of reported casualties, women, and girls are likely to be disproportionally disadvantaged as a result of mine/ERW incidents. They often suffer multiple forms of discrimination as survivors. Gender is a key consideration in victim assistance programming, but reporting was often limited to statistical disaggregation of casualties and service beneficiaries. In 2018, the Gender and Mine Action Programme published an Operational Guidance paper on victim assistance responsive to gender and other diversity aspects with examples of good practices.[31] The ICBL-CMC and Landmine Monitor Survivor Assistance Gender Focal Point participated in the launch.

Protection of mine victims and persons with disabilities in situations of risk, including situations of armed conflict, humanitarian emergencies, and natural disasters[32]

Generally, in conflict situations civilians remain extremely vulnerable and under-protected. The UN Secretary General found in 2019, “It is the cause of considerable concern, then, that the state of the protection of civilians today is tragically similar to that of 20 years ago.”[33] Moreover, during times of armed conflict or occupation, humanitarian emergencies, and natural disasters, mine/ERW victims and other persons with disabilities can face extreme challenges and barriers to having their rights respected and fulfilled, as well as to accessing adequate and appropriate services. This five-year period of the Maputo Action Plan was marked by increased conflict, state fragility, and growing numbers of refugees and displaced persons resulting from conflict, as well as by the impact of conflict and natural disasters gravely affecting victim assistance efforts in a number of States Parties.

States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty have committed to providing assistance to victims of these weapons, families of those killed or injured, and affected communities in accordance with relevant human rights law. Those which are States Parties to the CRPD also have an obligation, under Article 11, to ensure the protection and safety of persons with disabilities in situations of risk, including situations of armed conflict and humanitarian emergencies.

In 2018–2019, several Mine Ban Treaty States Parties with mine/ERW victims were in situations of armed conflict, including Afghanistan, Colombia, DRC, Iraq, Palestine, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, and Yemen.

An even greater number of the relevant States Parties—Afghanistan, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, DRC, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iraq, Mozambique, Palestine, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Turkey, Ukraine, Yemen, and Zimbabwe—have a Humanitarian Response Plan to address a humanitarian crisis, a protracted or sudden onset emergency that requires the ftnref3ftnref3ftnref3support of more than one UN agency for international humanitarian assistance.

During the Maputo Action Plan period it was recognized that much remains to be done to link response approaches to disaster and conflict to ensure respect for the rights of persons with disabilities, including mine/ERW victims.

The 15-year Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 adopted in March 2015 contains several references to persons with disabilities in emergency situations, due to active advocacy by disability rights groups. However, the final document omitted references to armed conflict due to sensitivities about the use of the term. Yet, armed conflict and attacks on healthcare providers were increasingly concerning and impacted the availability of services in affected countries.[34]

The charter on the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities into Humanitarian Action was adopted at the World Humanitarian Summit in Turkey in May 2016. To date only three of at least 12 Mine Ban Treaty States Parties that have situations of armed conflict have signed the charter. Those three countries are Afghanistan, Colombia, and Thailand.

An Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Task Team on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action was established in 2016 to develop and adopt implementation guidelines by the end of 2018, that was later extended to the end of 2019. In June 2019, the Security Council adopted its first text on the protection of persons with disabilities in conflict, Resolution 2475.[35]

Armed violence and conflict also directly impact victim assistance efforts. For example, in Afghanistan on 25 December 2018, militants from an unidentified non-state armed group attacked and entered the building of the newly established State Ministry for Martyrs and Disabled Affairs, resulting in more than 40 people killed and others taken hostage. The CRPD Committee Experts reviewing Iraq’s reporting in September 2019 found that the challenges and consequences of “18 years of war, armed conflict and terrorism…had ravaged Iraq and…had had a disproportionate impact on persons with disabilities.”[36] The conflict in Syria caused a massive displacement crisis. Refugee host countries, principally Mine Ban Treaty States Parties Turkey, Jordan, and Iraq, as well as Lebanon (a State Party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions), have received large numbers of persons who have fled Syria.

Natural disasters during the period were also devastating. In 2019, floods in Mozambique severely affected persons with disabilities in remote and rural areas. In 2015, flash rains and massive floods destroyed houses and infrastructure in the Sahrawi refugee camps situated near Tindouf in Algeria, near Western Sahara where hundreds of victims live with little outside support. An earthquake in Nepal saw the national survivor network redirect resources to assisting persons with disabilities in recovering from the destruction.

[1] The Monitor reports on the following Mine Ban Treaty States Parties in which there are significant numbers of victims: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Croatia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Jordan, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Palestine, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. This list includes 30 States Parties that have indicated that they have significant numbers of victims for which they must provide care as well as Algeria and Turkey, which have both reported hundreds or thousands of victims in their official landmine clearance deadline (Mine Ban Treaty Article 5) extension request submissions. It also includes Palestine and Ukraine, as both are indicated to have significant numbers of victims and needs, but have not yet comprehensively reported them. See, Algeria, Mine Ban Mine Ban Treaty Revised Article 5 Extension Request, 31 March 2011, http://bit.ly/2fzL7V7; and Turkey, Mine Ban Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 Extension Request, 28 March 2013, http://bit.ly/2fzQCmu.

[2] Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction (Mine Ban Treaty), Article 6.3, www.apminebanconvention.org/overview-and-convention-text/.

[3] See, “Final Report of the First Review Conference,” APLC/CONF/2004/5, 9 February 2005, para. 64; and “Nairobi Action Plan 2005–2009,” www.icbl.org/media/933290/Nairobi-Action-Plan-2005.pdf.

[4] Melanie Reimer and Teresa Broers, “Landmine Victim or Landmine Survivor: What Is in a Name?” The Journal of ERW and Mine Action 15 (2), 2011, www.jmu.edu/cisr/journal/15.2/focus/reimer/reimer.shtml.

[5] UN, “Final Report, First Review Conference,” Nairobi, 29 November–3 December 2004, PLC/CONF/2004/5, 9 February 2005, p. 33. Of these countries, 23 reported responsibility at the First Review Conference in Nairobi from 29 November to 3 December 2004, and with Ethiopia’s ratification of the Mine Ban Treaty on 17 December 2004, the number increased to 24.

[6] Maputo Action Plan, 27 June 2014, http://bit.ly/2e2R1Ol.

[7] “MAPUTO +15: Declaration of the States Parties to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction,” 27 June 2014, http://bit.ly/32RrJbu.

[8] Nairobi Action Plan, 2004–2009, Action #33.

[9] “Bridges” meetings were also held in Geneva and forged additional relationships among individuals working primarily on disability, development, or assistance to victims from a humanitarian perspective.

[10] Also sponsored by a Decision adopted by the European Union Council to support implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty.

[11] For more information on implementing victim assistance pillars through an action plan see, “Assisting the Victims: Recommendations on Implementing the Cartagena Action Plan 2010–2014,” Presented to the Second Review Conference of the States Parties to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention by Co-Chairs of the Standing Committee on Victim assistance and Socio-Economic Reintegration Belgium and Thailand, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 30 November 2009.

[12] Norway, “Draft Oslo Action Plan: Submitted by the President of the Fourth Review Conference,” 27 September 2019, http://bit.ly/344oc9P.

[13] See, Draft Oslo Action Plan, Action #4.

[14] Ibid., Action #32.

[15] Ibid., Action #33.

[16] Ibid., Action #34.

[17] Ibid., Action #35.

[18] Ibid., Action #36.

[19] Ibid., Action #39.

[20] Ibid., Action #40.

[21] Ibid., Action #41.

[22] Ibid., Action #42; CRPD Article 1 – Purpose – Article 29 – Participation in political and public life.

[23] Draft Oslo Action Plan Action #32; CRPD Article 33 – National implementation and monitoring.

[24] Draft Oslo Action Plan, Action #33; CRPD Article 33 – National implementation and monitoring.

[25] Draft Oslo Action Plan, Action #34; CRPD Article 31 – Statistics and data collection.

[26] Draft Oslo Action Plan Action #35; CRPD Article 25 – Health; CRPD Article 20 – Personal mobility; CRPD Article 26 – Habilitation and rehabilitation.

[27] Draft Oslo Action Plan Action #36; Article 4 – General obligations.

[28] Draft Oslo Action Plan Action #39; CRPD Article 25 – Health; CRPD Article 20 – Personal mobility; CRPD Article 26 – Habilitation and rehabilitation.

[29] Draft Oslo Action Plan Action #40; CRPD Article 27 – Work and employment; CRPD Article 28 – Adequate standard of living and social protection; CRPD Article 24 – Education.

[30] For more information about the impact of mines/ERW on children and the wider impact of armed conflict on children, see Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, “Landmines, Cluster Munitions and Unexploded Ordnances,” undated, childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/effects-of-conflict/landmines-cluster-munitions-and-unexploded-ordonances/; “Focus: Explosive remnants of war,” Victim Assistance Editorial Team at the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, quoted in in UNICEF, “The State of the World’s Children 2013: Children with disabilities,” 30 May 2013, www.unicef.org/sowc2013/focus_war_remnants.html; “Strengthening the Assistance to Child Victims,” submitted by Austria and Colombia, Maputo Review Conference Documents, undated, www.maputoreviewconference.org/fileadmin/APMBC-RC3/3RC-Austria-Colombia-Paper.pdf.

[31] See, GMAP, “Victim assistance responsive to gender and other diversity aspects,” Geneva 2018, www.gmap.ch/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/gmap_guidances_EN-web.pdf.

[32] Draft Oslo Action Plan Action #41; CRPD Article 11 – Situations of risk and humanitarian emergencies.

[33] UN Security Council, “Protection of civilians in armed conflict, Report of the Secretary-General,” S/2019/373, 7 May 2019, para. 4.

[34] See, Health Care in Danger website at healthcareindanger.org. See also, Safeguarding Health in Conflict website at www.safeguardinghealth.org/.

[35] UN, “Security Council Unanimously Adopts Resolution 2475 (2019), Ground-Breaking Text on Protection of Persons with Disabilities in Conflict,” 20 June 2019, www.un.org/press/en/2019/sc13851.doc.htm.

[36] OHCHR, “Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities discusses the impact of the armed conflict on persons with disabilities in Iraq,” 11 September 2019, www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24976&LangID=E.