Landmine Monitor 2019

Contamination & Clearance 20-Year Overview

Antipersonnel Mine Contamination

States Parties

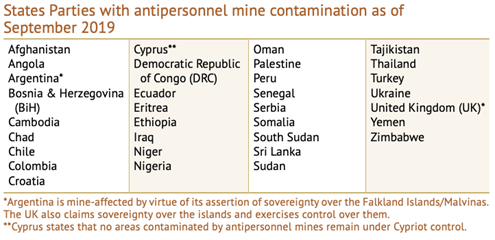

As of September 2019, a total of 33 States Parties have an identified threat of antipersonnel mine contamination on territory under their jurisdiction or control.

Another six States Parties that have already declared Article 5 completion or declared no contamination under their jurisdiction or control, currently have or are suspected to have residual contamination:

Algeria: Algeria declared fulfilment of its Article 5 commitments on 10 February 2017, validated at the Sixteenth Meeting of States Parties, in December 2017. However, it continues to find and destroy isolated mines. From December 2016 to October 2018, a total of 668 “isolated” antipersonnel mines were found and destroyed by army units designated to deal with residual contamination.[1] As Algeria declares the contamination and destroys the mines found within the year, it is compliant with the Mine Ban Treaty.

Burundi: Burundi declared fulfilment of its Article 5 commitments on 1 April 2014, but from 2017 to 2019, it found a few (four) isolated mines which it cleared and destroyed. It maintains a national police force trained by Mines Advisory Group (MAG) for the collection and destruction of residual contamination.[2] As Burundi declares the contamination and destroys the mines found within the year, it is compliant with the Mine Ban Treaty.

Djibouti: Djibouti completed its clearance of known mined areas in 2003 and France declared it had cleared a military ammunition storage area in Djibouti in November 2008, but there are concerns that there may be mine contamination along the Eritrean border following a border conflict, in June 2008. Djibouti has not made a formal declaration of full compliance with its Article 5 obligations.[3]

Kuwait: There have been a number of mine/explosive remnants of war (ERW) casualties reported in Kuwait since 1990. In 2017, there were four reported casualties, an increase from three in 2016.[4] In 2018, there were reports of torrential rain having unearthed landmines in the country, presumed to be remnants of the 1991 Gulf War.[5] The landmines are believed to be mainly on the borders between Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq, areas used by shepherds for grazing animals. Kuwait has not made a formal declaration of contamination in line with its Article 5 obligations.

Moldova: The Republic of Moldova, which had an Article 5 deadline of 1 March 2011, made a statement in June 2008 that suggested it had acknowledged its legal responsibility for clearance of any mined areas in the breakaway republic of Transnistria, where it continues to assert jurisdiction. However, this statement was later disavowed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, at the Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings in Geneva, on 2 June 2008.[6]

Namibia: Namibia made a statement at the Second Review Conference that it was in full compliance with Article 5, and it has reported that it has no mined areas under its jurisdiction and control. However, it is suspected that there are mined areas in the north of the country, for example, in the Caprivi region bordering Angola.[7]

States not party

In addition to the 33 States Parties contaminated by antipersonnel mines, there are also 26 states and other areas not party to the Mine Ban Treaty that have antipersonnel mine contamination. Lao PDR and Lebanon are party to the Convention of Cluster Munitions and have prioritized the clearance of cluster munition remnants.

New Contamination

New use of antipersonnel mines in recent and ongoing conflicts has exacerbated the remaining challenge for some states in addressing antipersonnel mine contamination. In some cases, this includes contamination by mines of an improvised nature. In many cases, the new contamination has not yet been fully quantified.

Over the last five years (2014–2018) there was new contamination in several States Parties including Afghanistan, Chad, Colombia, Iraq, Nigeria, Tunisia, and Yemen. In 2018, new use of antipersonnel mines was reported in States Parties Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Yemen.

Afghanistan: Continuing conflict between the government, the Taliban, and other armed groups is still adding new contamination, particularly by improvised mines.[8]

Chad: Mine incidents were reported in Chad in August 2016[9] and August 2017.[10] In April 2018, soldiers were killed and wounded during a series of operations in the Lake Chad region against Boko Haram forces that reportedly used landmines and suicide bombs.[11]

Colombia: The National Liberation Army (ELN) and drug-trafficking groups continue the struggle for control in about one-quarter of the country’s municipalities.[12] In ELN strongholds, such as the coastal department of Chocó, it has been reported that actors are emplacing mines in order to protect their territory.[13]

Iraq: Occupation of large areas of Iraq by Islamic State after 2014 added extensive contamination to Iraq’s existing legacy mined areas. Much of the new contamination comprises improvised mines and other explosive devices. Many of these devices are reported to be antipersonnel mines prohibited under the Mine Ban Treaty.

Nigeria: At the Eleventh Meeting of States Parties in November 2011, Nigeria declared that it had cleared all known antipersonnel mines from its territory.[14] However, since 2017, there have been reports of numerous incidents involving both civilian and military casualties from landmines and a range of other locally produced explosive devices planted by Boko Haram in the northeast of the country.[15]

Tunisia: Tunisia declared completion of clearance in 2009, but there have been reports of casualties from victim-activated improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in the last five years. It is likely that these devices were recently laid when they exploded.

Yemen: The ongoing conflict between the Houthi rebels in the north and the Saudi-led coalition in the south which flared in March 2015 has led to further contamination, although its full extent is unknown. Previously cleared areas, such as Aden (declared free of mines in 2003), are believed to be re-contaminated.[16]

Over the last five years there was unconfirmed use of antipersonnel mines in States Parties Cameroon and Mali.

Cameroon: Mine contamination has been reported in Cameroon since 2015, with incidents reported involving “roadside IEDs”.[17] Cameroonian military officials also reported in 2015 that large numbers of landmines had been planted by Boko Haram along Cameroon’s Nigerian border.[18]

Mali: Mali has confirmed antivehicle mine contamination and since 2017, it has experienced a significant increase in incidents caused by IEDs in the center of the country.[19]

There was confirmed new mine use by government forces in state not party Myanmar in 2018 and the first half of 2019. Landmine Monitor did not document or confirm any use of antipersonnel mines by Syrian government forces or by Russian forces in Syria during 2018. There was confirmed new use by non-state armed groups (NSAGs) in Myanmar and India. It is also likely that NSAGs have continued to use improvised mines in Syria, although this was not confirmed.

Extent of Contamination

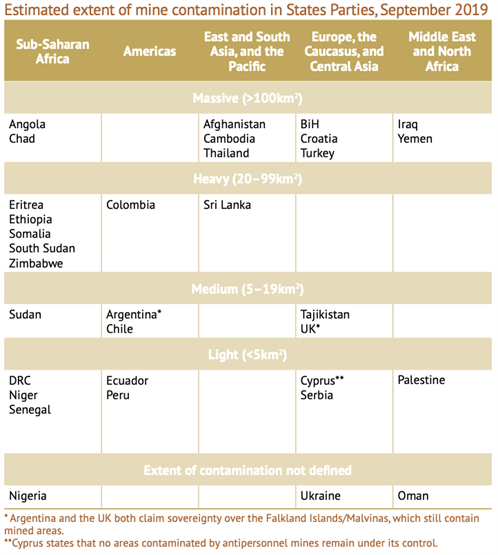

Based on information provided by official sources, massive antipersonnel mine contamination (defined by ICBL-CMC as more than 100km²) is believed to exist in States Parties Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Croatia, Iraq, Thailand, Turkey, and Yemen. One state not party, Azerbaijan and one other area, Western Sahara, are also believed to have massive contamination.

However, the extent of contamination estimated in some countries may in the future be subject to significant revision—either increased or decreased—based on survey results. For example, Ethiopia, which is currently believed to be heavily contaminated, with an estimated total of 1,056km² of contaminated land, has also reported that it expects only about 2% of suspected hazardous areas (SHAs) to contain mines.[20] Ukraine currently estimates around 7,000km² of contaminated land,[21] but this cannot be reliably verified until survey has been conducted.

Afghanistan, Yemen, and Iraq have all suffered recent contamination due to conflict and are required to reassess the scope and nature of their contamination. Ongoing conflict, insecurity and a lack of access to certain areas hamper these efforts.[22] Thailand, Cambodia, and Turkey still have to verify the extent of contamination along border areas where access has been problematic due to a lack of border demarcation, insecurity, or territorial disputes.[23] Turkey also has responsibility for the clearance of landmines in areas under its control in Northern Cyprus, although its most recent extension request in 2013 does not include a timeline for clearance of mines there.

Some states have continued to improve their understanding of the extent of contamination using land release methodologies to cancel suspected areas by non-technical survey and to reduce confirmed hazardous areas (CHAs) through technical survey. Angola, Croatia, Cambodia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Zimbabwe have all been able to reduce previous estimates of contaminated land through the implementation of survey.[24]

Several states not party for which no estimate of contamination is provided are believed to be massively contaminated. The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating North Korea and South Korea and the Civilian Control Zone (CCZ) immediately adjoining the southern boundary of the DMZ remain among the most heavily mined areas in the world, but no data is available on the extent of contamination.[25] Morocco, Myanmar, Russia, and Syria also have widespread contamination, but the extent is not known.

Landmine Clearance

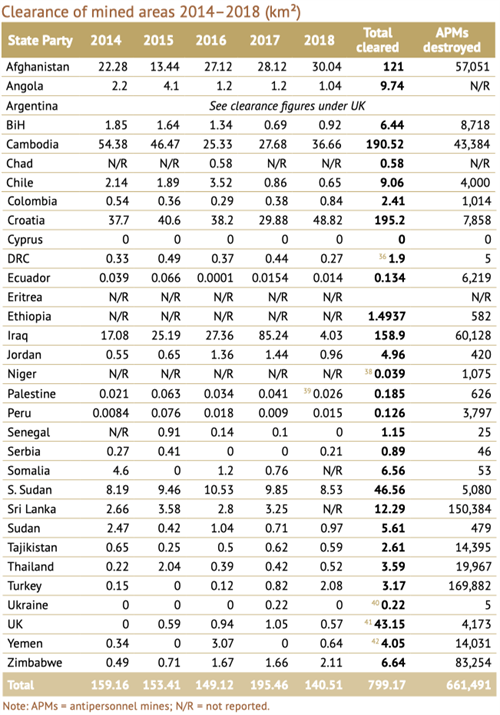

Among States Parties, total clearance of landmines in 2018 was at least 140km².[26] This represents a decrease from the estimated 195km² cleared in 2017. Over the five-year period from 2014–2018, total clearance of landmines among States Parties is estimated to be almost 800km², with at least 661,491 landmines destroyed.

However, these figures should be taken with caution due to the problems with obtaining accurate and consistent data. States Parties have sometimes provided conflicting data regarding clearance and have not always disaggregated mine clearance figures from the amount of land reduced through technical survey or canceled through non-technical survey. Not all States Parties have provided annual reports.

The figures may also underestimate the true amount cleared as clearance by some actors, such as armed forces, police, or commercial operators, may not be systematically reported. In some states, informal clearance or community-based clearance has been conducted, which is not subject to quality management and entry into the national databases. In some cases, land was cleared that was found to contain no mines. For further details of land release results for the period 2014–2018 and 20-year totals where available, see individual country profiles on the Monitor website.[27]

Based on the available data, Croatia has cleared the most land in the last five years at 195km², followed by Cambodia, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Afghanistan, Iraq, and Yemen have all continued landmine clearance despite ongoing conflict or insecurity. In Iraq, IED clearance has not been consistently included in clearance figures as it was not known how much of the contamination was by improvised mines. Reported figures for clearance in 2017 were high at over 85km², of which 55km² was areas affected by IEDs. However, the device type was not specified and large areas were reported as cleared but with no devices destroyed.[28] The amount of land reported cleared in Iraq in 2018 is low compared to 2017 figures, although over 14km² was released through survey. Yemen was able to clear 0.64km² as part of its emergency response in four governates from 2016–2018. It also destroyed over 14,000 antipersonnel landmines in the five years from 2014.[29]

Ecuador, Palestine, Peru, Serbia, and Ukraine have all cleared well under 1km² in the last five years. Ecuador’s clearance output dropped in 2016 due to an earthquake in April of that year that diverted the armed forces away from demining.[30] For Palestine, clearance in the West Bank is constrained by political factors, including the lack of authorization granted by Israel for Palestine to conduct mine clearance operations, although HALO Trust is currently conducting clearance in the West Bank.[31] Serbia has reported lack of funding, climatic conditions, unrecorded mined areas, and groups of mines laid haphazardly complicated clearance and survey efforts.[32] The extent of contamination in Ukraine is currently unknown and survey and clearance by international operators only began in 2015. Ukraine is currently establishing a mine action program.

Several countries have failed to report figures for mine clearance on a regular basis. Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Niger have not reported consistently on clearance since 2014.

In some countries, a decrease in clearance output has been matched by an increase in the amount of land released through survey. In Croatia, there was a 20% decrease in area cleared in 2017, although the amount of land released through survey was doubled.

No mine clearance was reported in the last five years in Cyprus or Argentina. Cyprus states that no areas contaminated by antipersonnel mines remain under its control.[33] Argentina reports that it is mine-affected as a result of its claim to sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Malvinas, but that it is unable to meet its Article 5 obligations because it has not had access to the islands due to the “illegal occupation” by the UK.[34]

In Algeria, which declared completion of clearance in 2016, no areas were reported as cleared, but 668 isolated mines have been destroyed between December 2016 and October 2018.[35]

In several states not party, mine clearance was known to have occurred between 2014–2018, although it was not formally reported. In Syria, international and national operators, both civilian and military have been undertaking clearance. There are media reports of clearance in India, and in Iran, commercial clearance occurred in oil- and gas-producing areas.[43]

Addressing the Impact Through Treaty Implementation

Completion of Article 5 commitments

Under Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty, States Parties are required to clear all antipersonnel mines as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the treaty. States Parties that consider themselves unable to complete their mine clearance obligations within the deadline may submit a request for a deadline extension of up to 10 years.

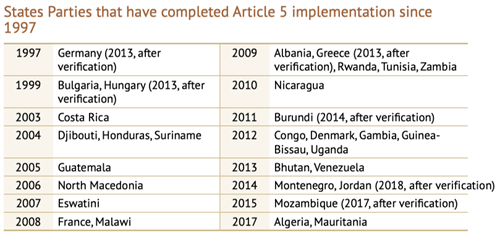

Since the Mine Ban Treaty came in to force in 1999, 33 states have reported clearance of all antipersonnel mines from their territory. Thirty-one were States Parties, one state not party (Nepal), and one other area (Taiwan).

The first States Parties to declare themselves mine-free were Germany in 1997 and Bulgaria and Hungary in 1999. Both Germany and Hungary later found SHAs, which were verified in 2013. El Salvador, a State Party, completed clearance in 1994 before the Mine Ban Treaty was created. In the first 10 years of treaty implementation (1999–2009), 10 States Parties declared themselves mine-free. This compares to 20 States Parties in the period 2010–2018.

In the last five years (2014–2018), five States Parties have declared themselves mine-free: Algeria 2017; Burundi 2014; Mauritania 2017;[44] Montenegro 2014; and Mozambique 2015. No state was declared free of antipersonnel mine contamination in 2018.

Nepal and other area Taiwan have completed clearance of known mined areas since 1999.

Several States Parties have declared themselves free of antipersonnel mines, although subsequent survey and verification revealed previously unknown SHAs. Burundi, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Montenegro, and Mozambique have all cleared and/or verified these suspected contaminated areas and fulfilled their Article 5 obligations. Algeria completed clearance of all known minefields in 2017 but continues to find and clear isolated mines.

Two States Parties that originally declared completion of clearance are now considered to be contaminated. Nigeria was declared mine-free in 2011, but during 2017–2019, antipersonnel mines of an improvised nature emplaced by Boko Haram have been reported in the northeast of the country. Jordan declared completion of clearance under the Mine Ban Treaty in 2012 but following verification work found further contamination in the Jordan Valley and along its northern border with Syria. Jordan undertook a process to verify and check these areas, and as of June 2018, stated that no further action is needed.[45]

Progress on meeting Article 5 deadlines

At the Third Review Conference in Maputo, Mozambique in June 2014, States Parties agreed to “intensify their efforts to complete their respective time-bound obligations with the urgency that the completion work requires.” This included a commitment “to clear all mined areas as soon as possible, to the fullest extent by 2025.”

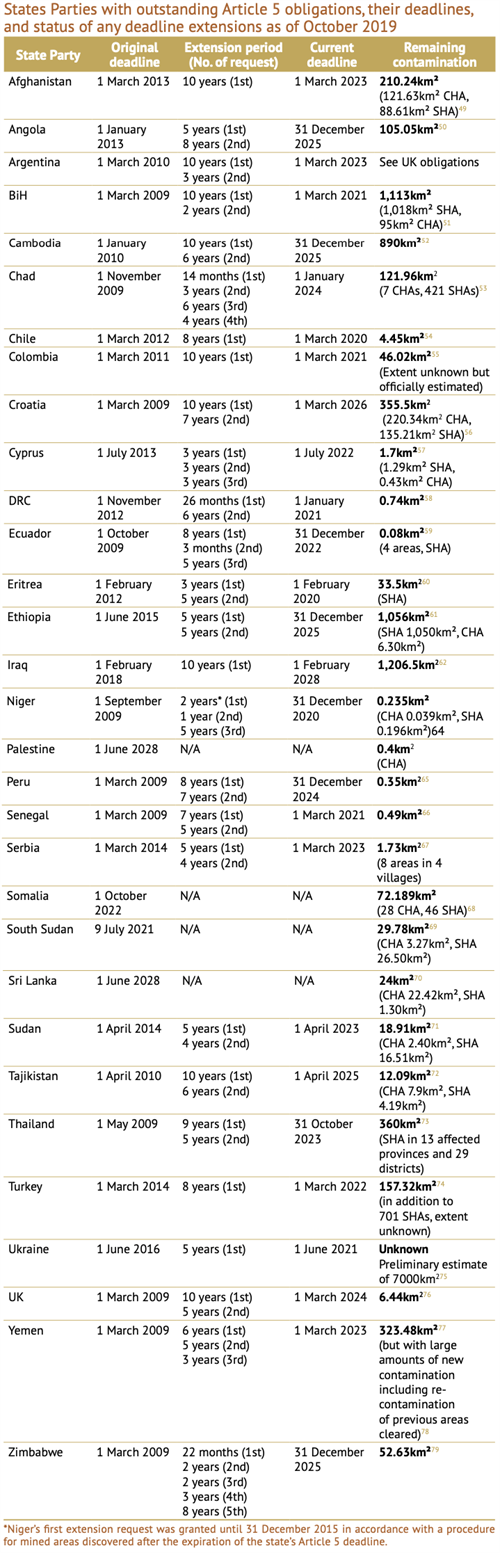

As of September 2019, 27 States Parties currently have deadlines to meet their Article 5 obligations before and no later than 2025. Four States Parties have deadlines after 2025—Croatia (2026), Iraq (2028), Palestine (2028), and Sri Lanka (2028). Palestine and Sri Lanka became States Parties in 2018 and are within their first 10-year deadline for completion of their Article 5 obligations. While Croatia has requested an extended deadline of 1 March 2026, it foresees that survey and clearance operations will be completed by the end of 2025, leaving only administrative/paperwork issues to be settled at the beginning of 2026.[46]

Yemen (current deadline March 2023) and BiH (current deadline March 2021) have both requested interim extensions to enable them to better define their remaining contamination. It is expected that both will submit further extension requests in March 2022 and March 2020 respectively. It is also expected that Iraq will require more time to assess the extent of new contamination. South Sudan has reported it is unlikely to meet its July 2021 Article 5 deadline and that it intends to submit an additional extension request for a period of five years beyond its July 2021 deadline.[47]

Zimbabwe, a State Party since 1999, has requested the most extensions to its Article 5 deadlines. Its fifth extension request has a deadline of 31 December 2025. Zimbabwe’s demining program was constrained by economic sanctions, a shortage of equipment, and a lack of international assistance.[48] However, Zimbabwe is now likely to meet its Article 5 deadline obligations, as are Sri Lanka, DRC, and Peru. It is also feasible that Chile, Ecuador, Niger, Senegal, Serbia, Tajikistan, and the UK can complete clearance before 2025.

Extension requests in 2019

In 2019, six countries requested extensions to their Article 5 deadlines: Argentina, Cambodia, Chad, Ethiopia, Tajikistan, and Yemen.

Argentina: Argentina has stated that it is unable to meet its Article 5 obligations because it has not had access to the Falkland Islands/Malvinas due to the “illegal occupation” by the UK.[80] In March 2018, the UK formally submitted a request to extend its Article 5 deadline by an additional five years until 1 March 2024 to complete the demining of the islands.[81] In March 2019, Argentina submitted an extension request for an additional three years until 1 March 2023.[82] This is a shorter timeframe than the 2018 UK extension deadline of 1 March 2024.

Cambodia: Despite over 25 years of humanitarian mine action, Cambodia has only addressed half of its antipersonnel mine contamination.[83] In April 2019, Cambodia submitted a second extension request for six years (2020–2025). Factors that may constrain compliance with the new extension request include un-demarcated border areas; available resources; inaccessible areas; competing development priorities and demands; and data discrepancies.[84] Cambodia also states that an additional 2,000 deminers will be needed to meet the 2025 goal,[85] along with US$165.3 million, from 1 January 2020–31 December 2025.[86]

Chad: Chad has requested four extensions to its Article 5 deadline to clear landmines from its territories, the most recent request of which was in April 2019 for a four-year extension until 2024. Despite each extension request including a plan to conduct survey to better understand the extent of contamination, the full extent of the problem remains unknown.[87] Lack of funding has been a recurring challenge for Chad in meeting its Article 5 obligations. Other factors have included issues related to weak management, security problems, and poor road networks.[88]

Ethiopia: Ethiopia has requested two extensions to its Mine Ban Treaty deadline, one submitted in March 2015 for five years until 1 June 2020,[89] and a second in 2019 for the period 2020–2025.[90] Ethiopia provided several reasons for failing to comply with its Article 5 deadlines, including insecurity; the lack of services and infrastructure necessary for demining operations; continuous redeployment of demining teams in scattered mined areas; the lack of precise information on the number and location of mined areas; and the identification of additional hazardous areas.[91] The 2019 extension request also cites insufficient donor funding as a key challenge to achieving the Article 5 commitment.[92] The cost of meeting the Article 5 deadline is estimated by Ethiopia to be $40,958,157, six million less than the first extension request.[93]

Tajikistan: Tajikistan submitted its second Article 5 deadline extension request in March 2019. The request is for an additional six years until 2025. The reasons given for not meeting its original 2020 deadline included insecurity along its border with Afghanistan and lack of permission to conduct demining in some of the western districts. Mined areas were reported as difficult to access and minefield records of poor quality.[94] Tajikistan also reported that survey work along the Tajik-Afghan border between 2010 and 2018 had identified an additional 41 mined areas (a total of 10.48km²), which had impeded progress towards the achievement of its Article 5 commitments.[95] The average clearance projected for each of the six years of the extension until 2020 is 1.5km² per year,[96] although in the last five years Tajikistan has cleared only 2.61km² of mined area. The preliminary estimated cost for the six-year extension until 2025 was $30 million, not including a $480,000 contribution from the Tajikistan state budget.[97]

Yemen: Yemen became a State Party in 1999 and has since had two five-year extensions to its deadline to meet its Article 5 obligation. Since April 2015, an escalation in conflict has disrupted clearance activity and shifted priorities to the emergency clearance of mines and ERW.[98] In March 2019, Yemen submitted a request for a third extension until 1 March 2023. Drawn up in consultation with UN Development Programme (UNDP), the request proposes an interim emergency response with the aim to conduct a national contamination survey in areas where security permits, to provide a realistic baseline for a subsequent 10-year extension request.[99] In addition to conducting the baseline, the Yemen Executive Mine Action Center (YEMAC) also aims to produce a revised workplan to meet its Article 5 obligation; to revise the national standards and strengthen the information management system; and to establish a coordination body.[100]

Eritrea: Eritrea has a deadline to meet its Article 5 obligations on or before 1 February 2020, but as of September 2019 it had yet to submit an extension request. It will be in violation of the treaty as of 1 February 2020 if it fails to submit a request for approval by States Parties at the November 2019 Review Conference in Oslo. Eritrea has not submitted an Article 7 transparency report since 2014 and failed to submit an updated Article 5 workplan as required by States Parties when granting its second deadline extension.

Challenges and Opportunities to Achieving Clearance Obligations

Considerable progress has been made since the Mine Ban Treaty entered into force in 1999, but there is still a need to increase the pace of survey and clearance activities to meet Article 5 obligations as soon as possible and to ensure significant progress towards the ambition of a mine-free world by 2025. There are still a number of challenges to be addressed by States Parties, but also opportunities that can assist States Parties to complete their obligations.

Funding

Several mine-affected countries are facing significant funding shortfalls, hampering their ability to meet their Article 5 deadline obligations. In the last five years, inadequate funding has been cited as a challenge by the following States Parties: Afghanistan, Angola, BiH, Cambodia, Chad, Croatia, DRC, Ethiopia, Iraq, Niger, Senegal, Serbia, Somalia, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Zimbabwe.

Reasons cited for the lack of funding for some countries include funding being prioritized for countries with new emergencies rather than legacy contamination and a reduction in funding to countries that have achieved or are close to reaching middle-income status.[101] In the past, Serbia has reported that mine clearance operations were affected when donor funding transferred to cluster munition clearance.[102] DRC has found mine action funding affected by the prioritization of funds for other humanitarian emergencies, including the recent Ebola outbreak.[103]

As the majority of funding comes from just a few donors, the top five being the United States (US), the European Union (EU), the UK, Norway, and Germany,[104] the loss of funding from a donor can dramatically impact a country’s mine action program. For example, Angola faced a reduction in funding for its mine action program following the loss of EU funding in 2016[105] and US funding in April 2018.[106]

Most States Parties do contribute an annual budget towards the cost of demining activities, although this is rarely enough to support their full mine action program. Government funds are often allocated to particular aspects of the demining program, particularly institutional support and salaries. The government of Angola has provided significant funding for mine clearance, although this has been almost exclusively in support of major infrastructure projects.

A few States Parties cover the full costs of mine action. Peru, in its revised second extension request, submitted in August 2016, estimated that US$38.6 million would be needed to complete clearance, all of which was due to be funded by the Peruvian government.[107] However, Peru also reported that while $3.88 million had been costed for 2018, the actual amount set in the annual budget was $2.36 million.[108]

Border control and territorial disputes

Several States Parties have stated that meeting their Article 5 deadlines is contingent on agreement around borders and territorial control.

A large proportion of mine contamination affects disputed areas along state borders, and a lack of agreement between states has hindered survey and clearance operations. For example, the current estimation of CHAs and SHAs in Ethiopia does not include information on contamination in the border areas between Ethiopia and Eritrea due to a lack of border demarcation preventing access and survey.[109] The UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) was terminated in 2008 and all mine action activities ceased. Ethiopia’s 2018 extension request notes that Ethiopia expects the discussion regarding the border areas will continue with the establishment of a joint border commission, although no indication was given as to when this will be established.[110]

Tajikistan’s ability to meet its new deadline partly rests on agreement of border clearance with Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. Tajikistan notes that both states have agreed for a joint commission to investigate the minefields and schedule clearance, but they are unable to provide an exact timetable.[111] Negotiations are also occurring with Afghanistan and border forces regarding access to and security for survey and clearance in some of the border areas.

The border between Thailand and Cambodia is still heavily contaminated and much of it has been subject to demarcation dispute, preventing effective clearance by either state. Both states have cited this as an obstacle to achieving their Article 5 deadline. However, in recent years, Cambodia and Thailand have come to agreement regarding their cooperation on the survey and clearance of these areas.[112]

There have been other positive developments among States Parties to agree clearance along their borders. Croatia signed an agreement with Hungary in 2016 to demine the border as part of a cross-border cooperation project with some of this clearance completed in 2017. In 2000, Ecuador and Peru established the Binational Cooperation Program (Programa Binacional de Cooperación), and a Binational Manual for Humanitarian Demining was adopted in 2013 to unify the demining procedures of both states in accordance with International Mine Action Standards (IMAS). The Ecuador-Peru Binational Demining Unit will carry out clearance of minefields along the border area, although the workplans of each country are slightly contradictory as to the amount of land to be cleared and when this will be done.[113]

In several states, clearance of landmines is impeded due to disputes over territorial control. While Cyprus stated in July 2013 that there were no remaining minefields in territories under its effective control,[114] landmine contamination remains in the buffer zone and in the Turkish-controlled areas. The breakdown of settlement talks facilitated by the UN in July 2017 resulted in access to SHAs being denied to the UN-supported mine action operations in Cyprus.[115] Turkey, which has mines along its borders with Syria, Armenia, Iran, Iraq, and Azerbaijan has only made marginal progress in addressing mine contamination in its territories, and its most recent extension request in 2013 does not include the clearance of mines in Northern Cyprus.

Mine action in Palestine is subject to the 1995 Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, under which the West Bank is divided into three areas according to civil and security control of Palestine and Israel. Most minefields are in Area C, where Israel has full civil and security control and will not authorize clearance by Palestinians.[116]

Ukraine also reported in its first Article 5 deadline extension request that it did not have access to some of the mined areas due to the occupying authority of the Russian Federation, which also prevented survey to understand the scale of contamination.[117] Argentina reports that it is mine-affected by virtue of its claim to sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Malvinas and has argued that it is unable to meet its Article 5 obligations because it has not had access to the islands.

Clearance in conflict

Mine action has typically occurred in post-conflict situations, but protracted conflict is increasingly resulting in mine action taking place in complex, insecure contexts that restricts or prevents access to areas, slows progress, and endangers the lives of deminers and other mine action staff.

In 2018–2019, conflict affected land release operations in 11 States Parties: Afghanistan, Cameroon, Colombia, Iraq, Niger, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Ukraine, and Yemen. Insecurity restricted access to some areas that are or may be affected by antipersonnel mines in States Parties Chad, Colombia, DRC, Ethiopia, Jordan, Senegal, Thailand, Turkey, and Ukraine.

Security and ongoing conflict in Afghanistan have affected clearance operations, slowing down and sometimes halting the progress of mine clearance.[118] Some provinces are inaccessible to mine action operators due to ongoing conflict between the government, the Taliban and other armed groups. In other areas, demining teams must gain the consent of all relevant parties.

In Colombia, the armed actions by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC), the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN), and drug-trafficking groups impact the ability for humanitarian demining groups to conduct survey and clearance.[119] Humanitarian demining operators had vehicles seized and damaged by FARC dissidents, in some cases resulting in the suspension of operations.

Ongoing conflict in Yemen means that the national contamination survey outlined in its 2019 extension request can only be conducted in areas where security permits.[120]

In the last five years, there have been several cases of humanitarian deminers killed, injured, or taken hostage in conflict-related attacks. In Afghanistan, 14 security incidents were reported in 2017, including a deminer murdered by anti-government elements in Nangarhar province in September. A total of 97 staff were abducted but later returned. Operators also reported equipment losses, including detectors, VHF radios, and mobile phones.[121] In 2018, six deminers were killed and 18 injured as a result of security incidents.[122]

In South Sudan, the release of mined areas plummeted in 2017 largely due to security concerns from the ongoing conflict, which significantly impeded mine action operations during the year. Four mine action personnel were seriously injured in an ambush, and there were several instances of criminality in which teams were robbed by armed groups.

However, despite ongoing conflict and insecurity, States Parties have also been able to make progress. In Iraq, operations have been undertaken to tackle the massive contamination by improvised mines and other ERW found in areas recaptured from NSAG Islamic State. Yemen has focused on emergency clearance and mine risk education since the outbreak of conflict in 2015, and plans to embark on a national contamination survey to re-assess the extent of the problem in the country.

In states like Iraq and Colombia where recent conflict has created fear, insecurity, and mistrust in government or outside groups, mine action operators have increasingly drawn on community liaison as part of their mine action approach to build community understanding of operations and enable access to affected areas.

Improvised mines and other improvised explosive devices

The use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) has dramatically increased in conflict areas in recent years, particularly in areas where insurgent forces are fighting. When victim-activated, these devices are also known as improvised mines or mines of an improvised nature. IEDs are often designed to be exploded by the presence, proximity, or contact of a person and so meet the definition of an antipersonnel mine and fall under the Mine Ban Treaty.

States Parties have several obligations with regards to improvised antipersonnel mines. This includes reporting any confirmed or suspected improvised mine contamination in their Article 7 transparency reports, making resources available to assess the extent of contamination, and to developing appropriate strategies to address it. States Parties are also required to exchange expertise to ensure that standards are adequate for addressing improvised mines. Affected countries and donors must be prepared to cover the costs of equipment and resources needed to deal with improvised mines, which may be higher than dealing with factory-manufactured mines. Finally, States Parties should also monitor progress towards meeting Article 5 obligations related to improvised mines to ensure compliance with the Mine Ban Treaty. A report published in 2017 recommended that contamination by improvised mines needs to be included within existing information management and reporting structures to ensure its location and extent is captured and a systematic response is conducted.[123]

In the last five years, confirmed or suspected improvised mine contamination and/or incidents and casualties were reported in the following States Parties: Afghanistan, Cameroon, Chad, Colombia, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, Tunisia, and Yemen, and states not party India, Lebanon, Libya, Myanmar, Pakistan, and Syria.

Afghanistan issued a policy paper on Abandoned Improvised Mines (AIM) in May 2018 that set out a number of principles to be followed by implementing partners. The Afghanistan Department for Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) reported that improvised mines are now being surveyed as SHA or CHA and when entered into Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) they are included as part of the Article 5 workplan.[124] The extent of this new contamination has yet to be determined by survey, but preliminary estimates in 17 of 22 affected provinces identified 152 hazards covering 228km2.

In Iraq, the Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) introduced a national standard on IEDs in 2016 and is working with the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) to update the standard to take into account the experience gained in tackling the dense contamination of improvised devices in areas liberated from Islamic State since 2016. However, it was not included in Iraq’s 2018 Article 5 deadline extension request or in its Article 7 report for 2017. Iraq must consider improvised mine contamination as part of its Mine Ban Treaty obligations.

Environment, climate, and topography

Several States Parties face the challenge of undertaking mine clearance in difficult environments which can slow the pace of clearance and increase costs.

In some countries, mine clearance has been prioritized in populated and more accessible areas, leaving the more remote and challenging areas to be tackled last. Chile is moving into the final phase of operations but has stated that it will face considerable challenges to clearance of the remaining contamination due to climate and topography. The mined areas in the Altiplano and the Austral Islands are difficult to access and are subject to heavy rains and snow, which restrict the length of the demining season.[125] At the beginning of operations in the Falkland Islands/Malvinas the UK prioritized the clearance of areas closest to settlements and civilian infrastructure, resulting in the release of areas closest to Port Stanley. The remaining minefields, cleared from 2018 onwards are particularly environmentally sensitive and challenging to clear due to penguin breeding areas and beach and sand dune areas.[126] The UK has therefore increased its funding commitment for this phase up to £27 million compared to the £11 million for the first four stages.[127]

In addition to the challenges of conducting clearance in remote and environmentally sensitive areas, there has been increasing use of IEDs in highly populated urban environments, the extent of which is creating new challenges for States Parties and mine action operators. In Iraq, Islamic State used improvised mines and booby-traps extensively in urban areas such as Mosul. Survey and clearance work in three-dimensional operating environments where the boundary between safe and unsafe areas is often less clear is challenging. In addition, the contamination in Iraq is often buried in building rubble resulting from heavy coalition airstrikes, which further complicates survey and clearance.

Natural disasters have also impacted on the progress of a few States Parties towards meeting their clearance obligations. Ecuador submitted a second request to extend its mine clearance deadline for three months until 31 December 2017 due to a serious earthquake on 16 April 2016, which required the diversion of the armed forces away from demining.[128]

Survey and land release

The resources for responding to landmine contamination are costly and limited and make it important to ensure that assets are deployed to achieve as much as possible. A major part of this is understanding where landmines are and where they are not. Under Article 5, States Parties are required to “make every effort to identify all areas under its jurisdiction or control in which antipersonnel mines are known or suspected to be emplaced.” However, identifying the true extent of contamination has been problematic for many States Parties.

The first global effort to understand the extent of contamination through the implementation of Landmine Impact Surveys was identified as bringing a more collaborative and deliberative approach and producing reports, databases, and outputs providing a more accurate description and analysis of the mine/unexploded ordinance (UXO) problems, thus providing a better basis for mine action decisions.[129] However, in many countries the surveys were also found to greatly over-estimate the extent of contamination. In addition, the systems to reduce SHAs were often over-cautious and wasteful, with an average of less than 3% of cleared land containing mines or UXO.[130]

The introduction of evidence-based decision-making processes through a combination of non-technical survey, technical survey, and clearance has greatly contributed toward increasing understanding of contamination and enabling more land to be released through cancelation and reduction, allowing for clearance resources to be targeted to land that is known to contain landmines.

Almost all States Parties that implement systematic mine clearance programs today now use land release methodologies (survey and clearance). This has led to significant advancement in understanding the actual extent of contamination, the cancelation or release of large areas of land previously considered contaminated, and better estimates of clearance timelines. For example:

- In Angola, survey was conducted in the lead up to the development of its 2017 extension request. All 18 provinces are now reported as surveyed and the process of non-technical survey allowed for significant cancelation, by as much as 90%, to the areas recorded in the database of the National Intersectoral Commission for Demining and Humanitarian Assistance (Comissão Nacional Intersectorial de Desminagem e Assistência Humanitária, CNIDAH).[131]

- In Cambodia, analysis of the data from 2014–2016 from the Cambodian Mine Action Authority (CMAA) national database showed that 40% of land was released through non-technical survey and 60% through technical survey and clearance.[132]

- Between 2014 and 2018, Croatia released 90.4km² of previously suspected land through survey. Croatia plans to further reduce SHA in the period 2019–2026.[133]

- South Sudan’s national mine action program has improved the accuracy of its estimates of contamination from landmines and other ERW since 2018. Re-survey of contaminated areas combined with an improvement in security conditions in certain areas and an overhaul of the mine action database contributed to the reduction of contamination from 89km² reported at the start of 2018, to 39.4km² at the end of the year.

- In Sri Lanka, non-technical survey began in June 2015 and was completed in February 2017. The estimates of total contamination have fallen sharply: from 506km2 at the end of 2010, to 98km2 at the end of 2012, to nearly 68.4km2 in 2015, and down to just under 24km2 as of April 2019.[134]

- In 2012, land release methodology was introduced in Thailand, which has allowed the accelerated release of safe land. Thailand estimates that at the time of its Article 5 extension request in March 2017, it had released around 80% of the total reported contamination.[135]

- Non-technical survey in Zimbabwe between 2013 and 2016 resulted in the cancelation of around 93% of SHAs.[136] Zimbabwe has reported that having completed survey, efforts are now focused on clearance. Zimbabwe is likely to meet its Article 5 deadline obligations by 2025.

In some States Parties, plans are underway to increase the use of land release approaches. In BiH, a country-wide assessment is to be conducted in 2018–2019 to establish a more accurate baseline of mine contamination and help to improve the efficiency of follow on survey and clearance operations. It is not clear if this has started.

The extent of contamination in both Ethiopia and Ukraine is currently extensive and it is expected that in both cases the SHA will be reduced through survey. In Ethiopia, it is expected that only about 2% of SHA will contain mines once survey is conducted.[137]

However, most States Parties still do not have a clear understanding of the full extent of their remaining contamination. The Committee on Article 5 Implementation assessed the degree of clarity of the remaining challenge, finding that only seven of the 25 States Parties assessed had provided a high degree of clarity in their reporting: Chile, Ecuador, Peru, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zimbabwe.

National ownership

The Maputo Action Plan makes specific reference to cooperation and partnership and that States Parties should take greater ownership over their responsibilities, including national funding and management of mine action programs.

Almost all States Parties with mine contamination have a national mine action program or institutions that are assigned to fulfill the state’s clearance obligations with a few exceptions:

- In Cyprus the mine action program has been coordinated by the UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) on behalf of the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP).[138]

- In Somalia, there was no government funding for the Somalia Explosive Management Authority (SEMA), and UNMAS stopped funding SEMA at start of 2016, in expectation that its legislative framework was due to be approved by the Federal Parliament and that funding for SEMA would be allocated from the national budget. In July 2018, SEMA reported that it was lobbying to get the necessary legislation passed in parliament and that once approved, SEMA would have a dedicated budget line included in the national budget.[139]

- In South Sudan, while it is planned that the National Mine Action Authority (NMAA) will ultimately assume full responsibility for all mine action activities, this has not yet occurred. This appears to be a result of financial and technical limitations of the NMAA that prevented effective management of operations and a change in the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) mandate that halted capacity-building of government institutions. However, in March 2019, UNMAS reported that it is preparing to transfer management and coordination responsibility to the NMAA.[140]

- In Ukraine, a national mine action program overseen by a national mine action authority and center is being developed with support from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Project-Coordinator and the GICHD. The donors have agreed to an extension of the project until the end of 2018, due to delays in the adoption of the mine action law.[141] This project has now received funding until October 2020.[142]

- In Yemen, YEMAC has been split due to the conflict, with one part based in Sanaa under the control of the Houthi armed movement and the other part in the southern city of Aden under the control of the Adrabbuh Mansur-led Yemeni government, supported by the Saudi and UAE-led coalition. The Sanaa office coordinates operations in the north and center of the country, while the Aden office oversees operations in southern provinces.

States Parties Nigeria and Oman do not have national mine action programs.

International support and standards

Since 1999, the GICHD has supported the implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty. It has supported States Parties to work towards the fulfillment of their Article 5 treaty-mandated obligations by providing capacity development and technical support in developing mine action strategies and plans; in implementing more effective and efficient land release processes; in managing mine action data through the use of the IMSMA; and in incorporating gender and diversity considerations into mine action programs.

The GICHD has supported UNMAS in managing the development and review of the IMAS, which have provided guidance and defined international requirements and specifications for mine action operations, enabling mine action programs globally to improve their safety and efficiency and to develop national mine action standards that reflect specific local realities and conditions.

The IMAS and the support from GICHD and its partners have supported States Parties (and some states not party) to improve and professionalize their mine action programs. It has also contributed towards greater consistency and accuracy in the reporting of land release targets and classifications as required in the Article 7 transparency reports. Most States Parties (26) have national mine action standards in place. Serbia and the UK both use IMAS, and DRC, Niger, and Ukraine have standards that are being reviewed or drafted. At least 19 States Parties use a version of IMSMA, and at least 25 States Parties have mine action strategic plans and/or workplans in place.

The Contribution of Clearance to Sustainable Development

Mine Action was initially framed in meeting the basic security needs of people, although in the wake of the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), mine action is increasingly being considered not only in terms of its humanitarian contribution, but also in terms of its contribution to longer-term development and socio-economic recovery. Mine action reporting, which initially focused mainly on outputs in terms of mines cleared and amount of land cleared, has adopted a stronger focus on outcomes and impacts in terms of the contribution of mine action to livelihood improvement, socio-economic recovery, and longer-term development.[143] There have also been efforts to ensure that mine clearance is prioritized to first meet the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable. In some States Parties, the mine action programs have spanned the years from an immediate post-war, humanitarian response to longer-term development.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the 17 SDGs were adopted by the UN Member States in January 2016. A study conducted by the GICHD and UNDP in 2017 recommended that while country-specific areas of work such as mine action are not explicitly identified in the SDGs, they can be addressed through the national-level SDG adaptation processes.[144] This can support States Parties in accelerating progress toward meeting treaty obligations, both in prioritizing mine action as a facilitator to meet the 2025 obligations and as a means to leverage funding.

Mine action-related activities have been integrated into national development plans, poverty reduction strategy papers, UN Development Assistance Frameworks (UNDAFs), or UNDP Country Programme documents by several countries.[145] States Parties have also highlighted the importance of the link between mine action and broader development goals within their mine action strategies. For example:

- Afghanistan, in its National Mine Action Strategic Plan 1395–1399 (2016–2020) has as its first goal the aim to facilitate development. This includes the sector improving understanding of how mine action contributes to human security and socio-economic development.[146]

- Cambodia adopted a specific SDG 18 to End the Negative Impact of Mines/ERW and Promote Victim Assistance. This includes the target to clear all identified mine and ERW-contaminated areas by the year 2030.[147] Mine action is also tied in closely with local development plans through a local-level planning process. Targets and indicators are being developed by the CMAA in terms of the contribution of mine action to other SDGs, including eradicating poverty, achieving zero hunger, promoting good health, ensuring decent work, and reducing inequalities. CMAA is customizing its IMSMA and training staff on data collection and analysis that will include SDG-related targets.

- Like Cambodia, state not party Lao PDR, also has an SDG specific to dealing with its ERW contamination problem. SDG 18, Lives Safe from UXO, recognizes the contribution of UXO clearance towards other SDGs, such as SDG 1, Ending Poverty.[148]

- Zimbabwe was supported by the GICHD to develop a National Resource Mobilization Strategy that will link mine action to the SDGs. ZIMAC plans to launch the strategy before the Fourth Review Conference in Oslo in November 2019.[149]

- The BiH National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025 recognizes the importance of linking mine action to the SDGs now that the country has moved on from the initial period of rehabilitation and stabilization following the conflict. The strategy commits to better understanding “the influences and possibilities brought by clearance in the sense of enabling both development and contribution to fulfilment of the SDGs,” and to the mobilization of funds for mine action.[150]

Gender and diversity

The importance of looking at gender and diversity in mine action has gained traction among States Parties in recent years. In relation to contamination and clearance, the consideration of gender and diversity is important in terms of the collection of information for planning and prioritization, in ensuring fair and equitable land release, and in paying attention to the gender balance on survey and clearance teams.[151] This not only allows an inclusive approach to gender equality but also ensures that mine action has a greater and more inclusive impact.

Several States Parties, particularly those with larger mine action programs, have included gender within their national mine action strategies. For example:

- Afghanistan has included gender and diversity as Goal 4 in its national mine action strategic plan with strategic objectives to develop a gender and diversity policy for the mine action program, to increase employment of women, persons with disabilities and other marginalized groups, to promote gender and diversity across management and coordination, and to undertake capacity-building and awareness-raising regarding gender and diversity.[152]

- BiH National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025 also acknowledges the importance of considering gender in mine action planning, implementation, and follow-up. It states the need to ensure that all mine action data is disaggregated by sex and age. The strategy also refers to the 2033 Law on Gender Equality in BiH and the Gender Equality Action Plan that supports equal representation of men and women.[153] Importantly, the mine action strategy also notes that the members of the newly established Demining Commission from the ministries of civil affairs, security and defense are also from the three constitutive nations of BiH, representing the Bosniak, Croat, and Serb peoples.[154]

- Goal 8 within the Cambodia National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025 includes the mainstreaming of gender and environmental protection in mine action.[155] Cambodia approved its Gender Mainstreaming Action Plan for Mine Action (2018–2022) in 2018.[156]

- The South Sudan National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2022 includes a section on gender and diversity, focusing on how different gender and age groups are affected by mines and ERW and have specific and varying needs and priorities. Guidelines on mainstreaming gender considerations in mine action planning and operations in South Sudan are also incorporated in the strategy.[157]

- The National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2019 of the DRC also includes a section of gender.

- The Tajikistan Mine Action Center has a National Gender Strategy.

There is evidence that some of the commitments towards gender and diversity outlined in the national strategies are being implemented. For example, the first all-women mine clearance team was established in Afghanistan in 2018.[158] However, while women are being recruited to clearance teams, there is less evidence of them being recruited to managerial and supervisory positions in the sector. In the DRC, it was reported that around 30% of operational staff in survey and clearance teams were female in 2019, but only around 7% of the managerial and supervisory positions were held by women.[159] In comparison, Tajikistan reported that it is a challenge to maintain a gender balance in demining teams due to those serving in the military being predominantly men. Tajikistan aimed to recruit more women to other roles, such as paramedics and quality management, in addition to increasing female civilian capacity in coordination with other implementing partners.[160]

Gender and diversity still appear not to be a priority for some States Parties. Gender is not referenced in Angola’s 2019–2025 Mine Ban Treaty Mine Action workplan, nor is it included in its national mine action standards in place in 2018.[161] In some countries, the utilization of military staff for demining operations also seems to limit the number of women in the sector. A report by the GICHD in 2012 noted that most of the staff of the Ethiopian Mine Action Office (EMAO) was transferred from the Ministry of National Defence and included a limited number of women. The report also noted that EMAO considered demining work not to be suitable for women.[162] While the Tajikistan National Mine Action Center (TNMAC) has a National Gender Strategy, it acknowledges that it is a challenge to maintain a gender balance in demining teams due to those serving in the military being predominantly men. However, Tajikistan noted that efforts would be made to recruit women to roles such as paramedics and quality management, in addition to increasing female civilian capacity in coordination with other implementing partners.[163]

Residual contamination

States that have complied with their Article 5 obligations and made all reasonable efforts to identify and clear all remaining mine contamination, may still find residual, previously unknown contamination at a later date. To ensure compliance with Article 5, States Parties have agreed to address these areas in accordance with the commitments made at the Twelfth Meeting of States Parties.[164] These commitments are as follows:

- To immediately inform all States Parties if a mined area or newly mined area is found and to destroy all the antipersonnel mines in the mined areas as soon as possible.

- To submit a request for an extended deadline, which should be as short as possible and no more than 10 years, if unable to destroy all the antipersonnel mines before the next Meeting of States Parties or Review Conference.

- To continue reporting obligations under Article 7 of the treaty and to provide all other relevant updates.

Several States Parties found such residual contamination after declaring completion. Burundi, Germany, Greece, Hungary, and Mozambique all addressed and completed their obligations under Article 5. Algeria continues to find isolated mines which it clears within the year and so is considered to be compliant with the Mine Ban Treaty.

National strategies and completion plans need to make provisions for sustainable national capacity to address any previously unknown areas. Several States Parties have begun to plan for the possibility of having to deal with residual contamination following the completion of their Article 5 obligations.

- The BiH National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025 includes a section on management of residual contamination and national capacities. It specifies that the armed forces of BiH and the Administrations for Civil Protection will play a role in this, and that a strategy for dealing with the residual threat should be created by 2022.[165]

- Goal 7 of the Cambodia National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025 aims to establish national capacity to address residual mine threats after 2025. This includes strengthening national capacity, including the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, Cambodian Mine Action Center, and the police; enhancing and sharing mine action knowledge within the sector and beyond; and reviewing the legal, institutional, and operational framework to address residual threats.[166]

[1] Algeria, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form I, 31 October 2018, p. 39.

[2] Burundi, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, 4 October 2019, p. 6.

[3] See, ICBL-CMC, “Country Profile: Djibouti: Mine Action,” 17 December 2012, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/djibouti/mine-action.aspx.

[4] ICBL-CMC, “Country Profile: Kuwait: Casualties,” 10 October 2018, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/kuwait/casualties.aspx.

[5] “Torrential downpour unearths landmines in Kuwait,” The National, 21 November 2018, http://bit.ly/2NjHzFh.

[6] See, ICBL-CMC, “Country Profile: Moldova: Mine Action,” 17 December 2012, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/moldova/mine-action.aspx.

[7] ICBL-CMC, “Country Profile: Namibia: Mine Action,” 13 July 2011, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/namibia/mine-action.aspx.

[8] See, for example, reports that armed opposition groups mined the highway linking Kabul and Ghazni during fighting in August 2018. “Intense fighting as Taliban presses to take Afghan city,” Reuters, 12 August 2018.

[9] “Boko Haram landmine kills four Chadian soldiers,” Reuters, 27 August 2016, www.reuters.com/article/us-nigeria-security-chad-idUSKCN1120KY.

[10] “Tchad: un véhicule d’orpailleurs saute sur une mine près de Zouar dans le Tibesti, 8 morts et 11 blessés” (“Chad: A miners’ vehicle hits on a mine near Zouar in Tibesti, 8 dead and 11 wounded”), Tchad Convergence, 20 August 2017, http://bit.ly/2pS2rvk.

[11] “Nigeria: Boko Haram – Military Winning the Lake Chad War Despite Losses – General Irabor,” Premium Times, 29 April 2018, http://bit.ly/2JmZKIU.

[12] International Crisis Group, “Risky Business: The Duque Government Approach,” 21 June 2018; and Mine Action Review interviews with Pauline Boyer and Aderito Ismael, Humanity & Inclusion (HI), in Vista Hermosa, 8 August 2018; with Esteban Rueda and Sergio Mahecha, Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA), in Vista Hermosa, 9 August 2018; with Hein Bekker and Emily Chrystie, HALO Trust, in San Juan de Arama, 10 August 2018; and with John Charles Cagua Zambrano and Francisco Profeta Cardoso, Columbian Campaign to Ban Landmines (CCCM), in Centro Poblado de Santo Domingo, 11 August 2018.

[13] Email from Vanessa Finson, NPA, 11 May 2018, quoted in Mine Action Review, “Clearing the Mines 2018,” 1 October 2018.

[14] Statement of Nigeria, Mine Ban Treaty Eleventh Meeting of States Parties, Phnom Penh, 29 November 2011. In January 2017, a civil war-era landmine was found in Ebonyi state, which villagers thought was an IED. Police forensics concluded it was a landmine left over from the conflict that ended 47 years previous, which had washed up in a river. A bomb squad destroyed the device, and according to the police, the area was searched and no evidence of other contamination was found. J. Eze, “Nigeria: Civil War Explosive Found in Ebonyi Community – Police,” AllAfrica, 17 January 2017, http://allafrica.com/stories/201701180015.html.

[15] J. Payne, “Nigeria’s military believes it has Boko Haram cornered, but landmines are getting in the way,” Reuters, 2 May 2015, http://bit.ly/2MQLGK0; and “Nigeria: Landmine Blast Kills Soldier, Three Vigilantes in Sambisa Forest,” AllAfrica, 24 April 2015, http://allafrica.com/stories/201504240329.html.

[16] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 8 August 2019, p. 9.

[17] UNMAS, “Mission Report: UNMAS explosive hazard mitigation response in Cameroon, 9 January–13 April 2017,” 30 April 2017, p. 11; and email from Camille Aubourg, UNMAS, 17 September 2018.

[18] M.E. Kindzeka, “Land Mines Hamper Cameroon, Chad in Fight Against Boko Haram,” Voice of America News, 3 March 2015; and M.E. Kindzeka, “Boko Haram Surrounds Havens with Land Mines,” Voice of America News, 24 May 2015.

[19] UNMAS, “Programmes: Mali,” 31 August 2019, www.unmas.org/en/programmes/mali.

[20] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2019, pp. 10 and 35. However, Ethiopia has reported different estimates of the percentage of SHAs expected to be confirmed, between 0.5% and 3%. See the Revised National Mine Action Plan for 2017–2020, October 2017, pp. 1–3, & 9; statement of Ethiopia, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Committee on Article 5 Implementation, Geneva, 8 June 2017; Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2016), Form C; and Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2015, pp. 7 and 42.

[21] Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 1 November 2018, p. 1.

[22] Afghanistan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 Extension Request, August 2012, p. 23; Yemen, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 8 August 2019, p. 9; and Iraq, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, March 2017, pp. 10–12, & 88.

[23] Improved relationships between Thailand and Cambodia have led to cooperation to survey and clear border areas. See, “CMAC, Thais join forces to clear mines at border provinces,” The Phnom Penh Post, 24 September 2019, http://bit.ly/2pRUu9t.

[24] Angola, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 31 August 2017, p. 5; CMAA, “National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025,” p. 9; and Croatia, Mine Ban Treaty Second Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 29 March 2018, p. 7.

[25] Response by the Permanent Mission of South Korea to the UN in New York, 9 May 2006; and K. Chang-Hoon, “Find One Million: War with Landmines,” Korea Times, 3 June 2010.

[26] This refers to land cleared and does not include land released or canceled through survey.

[27] See Mine Action country profiles available on the Monitor website, www.the-monitor.org/cp.

[28] See ICBL-CMC, “Country Profile: Iraq: Mine Action,” 16 November 2018, http://the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/iraq/mine-action.aspx.

[29] Yemen, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 8 August 2019, pp. 14–15; and Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form J, p. 25.

[30] Ecuador, Article 5 Implementation Update, June 2017.

[31] HALO Trust, “West Bank,” undated, www.halotrust.org/where-we-work/middle-east/west-bank/.

[32] Serbia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, March 2018, p. 7.

[33] Cyprus, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 4.

[34] Argentina, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form A, 8 April 2010.

[35] Algeria, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form I, 31 October 2018, p. 39.

[36] 2014–2017 figures reported in DRC, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, Form D, 2017, p. 10. Figures reported by ICBL-CMC for 2014–2017 are lower (2014: 0.22km²; 2015: 0.31km²; 2016: 0.37km²; 2017: 0.44km²).

[37] Mine clearance figure for period 2016–2018. Ethiopia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form D, p. 4; Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2019, pp. 8 and 13.

[38] Figures for period June 2011 to May 2014. Niger, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for period June 2011–May 2014), Form I, p. 19.

[39] US Department of State Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, “To Walk the Earth in Safety,” US: PM/WRA and CISR, 2019, p. 46.

[40] Ukraine is currently establishing a mine action program and has yet to survey the SHA. Figures given for clearance in 2017 are for clearance by HALO Trust. See ICBL-CMC, “Country Profile: Ukraine: Mine Action,” 12 November 2018, www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2018/ukraine/mine-action.aspx.

[41] Land release figures for Phase 5a of the clearance of the Falkland Islands/Malvinas, November 2016–March 2018 are given as 4.81km². UK, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 2018, p. 6, and Annex 1, p. 5.

[42] The figure of 0.64km² is for clearance as part of the emergency response (2016–2018) in four governates. The figures for ordnance destroyed are for five years from 2014, but with the large majority having been cleared in the years 2016–2018. Yemen, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 8 August 2019, pp. 14–15; and Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form J, p. 25.

[43] ICBL-CMC, Landmine Monitor 2018, www.the-monitor.org/LMM2018.

[44] Mauritania completed clearance in December 2017 and on 29 November 2018 at the Seventeenth Meeting of States Parties in Geneva, announced that it had fulfilled its obligation under Article 5 of the treaty.

[45] Email from Col. Mohammed Breikat, National Director, National Committee for Demining and Rehabilitation (NCDR), 19 September 2019.

[46] Mine Ban Treaty Second Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 29 March 2018, additional information submitted 21 June 2018, p. 1.

[47] Presentation by Jurkuc Barach Jurkuc, Mine Ban Treaty Intersessional Meetings, Geneva, 7–8 June 2018.

[48] Analysis of Zimbabwe’s Article 5 deadline Extension Request, submitted by the President of the Mine Ban Treaty Eighth Meeting of States Parties on behalf of the States Parties mandated to analyze requests for extensions, 24 November 2008.

[49] As of December 2018. Afghanistan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), p. 6.

[50] As of April 2019. Angola, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 4.

[51] As of end 2018. BiH, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 7. There are discrepancies with the data provided in the Second Mine Ban Treaty Extension Request, March 2018.

[52] As of December 2018. Cambodia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), p. 5. CMAA, “National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025,” p. 9, gives the figure as 946km².

[53] Email from Soultani Moussa, Manager/Administrator, HCND, Chad, 19 June 2018, quoted in Mine Action Review, “Clearing the Mines 2018,” 1 October 2018.

[54] As of December 2018. Chile, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form F, p. 17.

[55] Colombia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, 30 April 2018. The statement of Colombia at the Seventeenth Meeting of States Parties, Geneva, 26–30 November 2018, stated that estimated contamination was 51.24km², but this amount was reportedly reduced through demining efforts.

[56] As of end 2018. Croatia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 9.

[57] As of May 2019. UNMAS, “Programmes: Cyprus,” May 2019, www.unmas.org/en/programmes/cyprus.

[58] As of December 2018. DRC, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), p. 4. This is more than the 0.50km² recorded in 2017. It is reported that 30 new zones of 470,782m² were identified.

[59] As of 31 December 2018. Ecuador, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form D, p. 9.

[60] As of December 2013. Eritrea, Mine Ban Treaty Second Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 23 January 2014, p. 8. No updates on the extent of contamination since 2013.

[61] As of April 2019. Ethiopia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form D, p. 4; and Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2019, p. 9.

[62] As of December 2019. Iraq, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), pp. 20–21. This compares to the 1,195.56km² of contamination identified in Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, March 2017, pp. 26 and 78. The extent of recent contamination has not been fully quantified.

[63] At end 2018. Jordan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), pp. 13–14. At the end of 2017, the total area in need of verification was just under 4.25km² across a total of 54 areas (36 in the Jordan Valley and 18 in the northern borders).

[64] Niger, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for 2013–April 2018), Annex 1, p. 19.

[65] As of December 2018. Peru, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form F, p. 11.

[66] As of 31 December 2018. Senegal, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form D, p. 3. This figure is inconsistent with figures given in the Article 7 reports of previous years.

[67] As of April 2019. Serbia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 4.

[68] Full extent of contamination is still unknown. Somalia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 5. This number is slightly different to survey conducted before 2018, which gave the figure 72.289km². Somalia notes in the Article 7 report for 2018 that it was not able to provide a full picture of landmine contamination due to the transfer of the IMSMA database from UNMAS to SEMA. Different figures for the extent of contamination are also provided on p. 20.

[69] South Sudan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 3.

[70] As of April 2019. Sri Lanka, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), p. 9.

[71] As of 31 December 2018. Sudan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 8.

[72] As of 31 December 2018. Tajikistan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form D, pp. 5 and 6.

[73] As of December 2018. Thailand, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form D, p. 3. In the Five-Year Humanitarian Mine Action Plan 2018–2023, TMAC, March 2019, p. 11, it records the remaining contamination in 10 provinces and four regions.

[74] As of December 2018. Turkey, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form D, p. 8.

[75] Ukraine, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 1 November 2018, p. 1.

[76] As of 31 March 2018. Email from an official in the Counter Proliferation and Arms Control Centre, Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO), 21 August 2018.

[77] As of 1 March 2017. Yemen, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report, 31 March 2017, Form D, pp. 4 and 9.

[78] Yemen, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 8 August 2019, p. 9.

[79] As of end 2018. Zimbabwe, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form D, p. 2.

[80] Statement of Argentina, Mine Ban Treaty Second Review Conference, Cartagena, 30 November 2009.

[81] UK, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 29 March 2018.

[82] Argentina, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 19 March 2019.

[83] Cambodia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 Extension Request, 27 March 2019, p. 6.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Ibid., p. 7. Cambodia is considering deploying Royal Cambodian Army soldiers to meet this need, p. 9.

[86] Ibid., p. 55. This figure does not include an additional US$8.1 million for clearance of antivehicle mines; $38.6 million for management and coordination; $118.9 million for cluster munitions clearance; or $41.3 million for ERW clearance. The total sum is $372.2 million.

[87] Chad, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 16 April 2019.

[88] NPA, “Mine Action Review: Clearing Cluster Munition Remnants 2019,” 1 August 2019, p. 30; “Tchad: grève des démineurs restés 10 mois sans salaire” (“Chad: deminers strike after 10 months without pay”), Agence de Presse Africaine, 10 May 2017, http://apanews.net/fr/news/tchad-greve-des-demineurs-restes-10-mois-sans-salaire; and email from Julien Kempeneers, HI, 26 September 2017.

[89] Ethiopia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2015, p. 10.

[90] Ethiopia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2019.

[91] Ibid., pp. 8–9.

[92] Ibid., pp. 9, 14–15.

[93] Ibid., p. 11.

[94] Email from Muhabbat Ibrohimzoda, TNMAC, 27 April 2018; and interview, in Dushanbe, 30 May 2018, quoted in Mine Action Review, “Clearing the Mines 2018,” 1 October 2018.

[95] Tajikistan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2019, p. 37; and Tajikistan answers to the questions concerning the request submitted by Tajikistan, Committee on Article 5 Implementation, 2019, p. 1.

[96] Tajikistan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), p. 8.

[97] Tajikistan, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2019, pp. 9 and 23.

[98] Yemen, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 8 August 2019, p. 3.

[99] Yemen, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 28 March 2019, pp. 4 and 5.

[100] Yemen, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), 8 August 2019, p. 25.

[101] Chris Loughran and Camille Wallen, “State of Play: The Landmine Free 2025 Commitment,” MAG and HALO Trust, December 2017, p. 8.

[102] Mine Ban Treaty Second Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 14 March 2018, p. 11.

[103] NPA, “Mine Action Review: Clearing Cluster Munition Remnants 2019,” 1 August 2019, p. 116.

[104] See the Landmine Monitor chapter on Mine Action Support.

[105] Emails from Gerhard Zank, HALO Trust, 15 June 2018; from Joaquim da Costa, NPA, 10 May 2018; and from Jeanette Dijkstra, MAG, 24 April 2018, quoted in Mine Action Review, “Clearing the Mines 2018,” 1 October 2018; and Chris Loughran and Camille Wallen, “State of Play: The Landmine Free 2025 Commitment,” MAG and HALO Trust, December 2017.

[106] Emails from Gerhard Zank, HALO Trust, 15 June 2018; from Joaquim da Costa, NPA, 10 May 2018; and from Jeanette Dijkstra, MAG, 24 April 2018, quoted in Mine Action Review, “Clearing the Mines 2018,” 1 October 2018.

[107] Mine Ban Treaty Second Article 5 deadline Extension Request (revised), July 2016, p. 18.

[108] Peru, Updated National Plan for Humanitarian Demining 2018–2024, May 2018, p. 11.

[109] Ethiopia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, 31 March 2019, p. 34.

[110] Ibid., p. 9.

[111] Tajikistan answers to the questions concerning the request submitted by Tajikistan, Committee on Article 5 Implementation, 2019, p. 5.

[112] “CMAC, Thais join forces to clear mines at border provinces,” The Phnom Penh Post, 24 September 2019, http://bit.ly/2pRUu9t; and Cambodia, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 Extension Request, 27 March 2019, p. 44.

[113] Ecuador, Mine Ban Treaty Article 5 deadline Extension Request, Additional information, 8 September 2017, p. 10; and Peru, Updated National Plan for Humanitarian Demining 2018–2024, May 2018, p. 17.

[114] Cyprus, Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 Report (for calendar year 2018), Form C, p. 4.