Cluster Munition Monitor 2020

The Impact

Jump to a specific section of the chapter:

Introduction | Contamination | Casualties | Addressing the Impact: Coordination, Clearance, Risk Education, Victim assistance

This summary highlights developments and challenges in assessing and addressing the impact of cluster munition contamination and casualties, through land release including clearance, risk education, and victim assistance during the reporting period prior to the Second Review Conference of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in Switzerland in 2020.[1] The Review Conference will mark the adoption of the Lausanne Action Plan, a new set of five-year strategic commitments to further states’ efforts to address the impact of cluster munitions. The summary reports on the impact of cluster munitions globally. It also focuses on the efforts and challenges to address the impact in the States Parties with responsibility for clearance of cluster munition remnants and to cluster munition victims. It is these states to which the convention’s obligations and the action plan commitments legally and directly apply.

The improvement of survey processes and data collection has enabled better understanding of the extent of cluster munition remnant contamination in States Parties, and has allowed the development of more realistic plans and better targeting of clearance resources.[2] In the 10 years since the Convention on Cluster Munitions came into force, States Parties have cleared at least 559km² of cluster munition contaminated land, and cleared and destroyed more than 450,000 submunitions. However, in some States Parties the rate of clearance has been slow, and in others there has been virtually no progress.

While in 2020 two States Parties announced fulfilment of their Article 4 clearance obligations, 10 States Parties remain contaminated. A further 13 non-signatories and three other areas have, or are believed to have, land containing cluster munitions on their territories.

The Convention on Cluster Munitions has successfully increased awareness of the objective of preventing new casualties and ending the suffering caused by these indiscriminate weapons. Ultimately, that awareness has resulted in more detailed and swifter reporting on casualties of cluster munition use. During the 10-year period of Cluster Munition Monitor reporting, 2010–2019, 4,315 new cluster munition casualties were recorded in 17 countries and three other areas. The vast majority of new casualties, 3,575 (83%), recorded during that time occurred in Syria as the result of new use, which included both attacks and contamination by cluster munition remnants.[3] Various estimates for casualties in cluster munition-affected countries globally since the 1960s are roughly between 56,000 and 86,000. The present total of recorded cluster munition casualties is 22,050, both from cluster munition remnants and from attacks in 34 countries and three other areas.[4]

Since entry into force of the convention some 40% of casualties were children. Affected States Parties clearly recognize children as a key risk group requiring specific and tailored risk education, because they are often growing up in contaminated areas, lack knowledge of the risks and are prone to picking up and playing with items, very often resulting in multiple casualties. Adults frequently become casualties of cluster munitions during everyday livelihood activities, where work or subsistence occupations such as agriculture, building, herding, hunting, and burning to cook or clear land, puts them at risk. While children often touch, move, or play with cluster submunitions unaware of the danger, adults do the same, but with knowledge of the risks. Adults are recorded taking risks by attempting to pick up and move submunitions to what they hope will be a safer place, out of reach of children and the community. Cluster munitions often impact the most vulnerable groups in a society, such as people who collect scrap metal for a living, migrant workers, and refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs).

The majority of cluster munition contaminated States Parties have some form of provision of risk education. In some States Parties, risk education is provided for a variety of explosive ordnance, including cluster munitions. In States Parties with greater cluster munition contamination, risk education is more targeted to the nature of contamination and behaviors associated with cluster munition remnants.

The existing level of the risk education response at the national level can be viewed as an achievement, particularly given the little attention and resources directed towards risk education internationally since the convention entered into force. A change occurred in 2019, which saw an increased focus on risk education due to the dramatic rise in casualties, particularly in the Middle East. However, more must be done to ensure that risk education can continue to improve and innovate, and provide tailored and contextual risk education to populations living with new and with legacy cluster munition remnants contamination.

The majority of all recorded cluster munition casualties for all time, 59%, occurred in States Parties. These states have obligations to assist the victims under the convention. The Convention on Cluster Munitions was the first multilateral treaty to make the provision of assistance to the victims of a specific weapon a formal obligation for all States Parties with victims.[5] After its entry into force in 2010, the convention continues to set the highest legal standards for victim assistance.

Among the 14 States Parties which have had cluster munition casualties recorded, 12 have recognized responsibility for cluster munition victims. Methods and approaches for implementing victim assistance vary significantly, particularly between those States Parties which have hundreds or thousands of cluster munition casualties and those with few reported casualties.

Cluster Munition Remnants Contamination

Cluster munition contamination in States Parties

States Parties that have completed clearance

When the Convention on Cluster Munitions entered into force on 1 August 2010, out of the 40 States to have ratified it, 17 reported Article 4 obligations for clearance, destruction of cluster munition remnants and the provision of risk education. Each of these States Parties was obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under its jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention.

Six States Parties have formally reported completing clearance of contamination between 2010 and 2020, including Croatia[6] and Montenegro,[7] both of which declared fulfilment of their Article 4 obligations in July 2020, before their deadlines of 1 August 2020 (see table below). However, Mauritania, which had reported fulfilment of its clearance obligations in September 2013, has since reported finding new cluster munition contamination.[8]

States Parties Albania, Guinea-Bissau and Zambia all completed clearance before the convention came into force.[9]

No State Party completed clearance of cluster munition remnants in 2018 or 2019.

States Parties that have declared fulfilment of clearance obligations since 2010[10]

|

Grenada, September 2012 |

|

Norway, September 2013 |

|

Mauritania, September 2013* |

|

Mozambique, December 2016 |

|

Croatia, July 2020 |

|

Montenegro, July 2020 |

*Mauritania has since reported finding new cluster munition remnants contamination.

States Parties remaining to be cleared

As of 1 August 2020, 10 States Parties had Article 4 clearance obligations: Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Chile, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia. Somalia became a State Party in 2015 and reported obligations under Article 4 in its initial Article 7 report in 2019.[11]

For some States Parties, including Colombia, Palau, and the United Kingdom (UK), the situation regarding contamination is unclear or has varying interpretations.

Colombia stated that it had no cluster munition remnants contamination on its territory in 2017 and no known evidence of contamination has been found, [12] however no survey has been undertaken to confirm this.[13] An investigation showed that a World War II-type “cluster adapter” of United States (US) origin was used during an attack at Santo Domingo in 1998.[14] The Inter-American Human Rights Court found the Colombian Air Force used an AN-M1A2 bomb, which it said meets the definition of a cluster munition.[15]

Palau reported that in 2010, two World War II “cluster adapter” AN-M41A1 submunitions were identified and destroyed,[16] but since then no more have been located through survey or clearance. It is therefore believed that Palau is now free of cluster munitions, although it continues to suffer a high level of contamination from other World War II-era explosive remnants of war.[17]

The UK, due to its claim of sovereignty over the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas may have some residual cluster munition remnants contamination present within mined areas that are still to be cleared.[18] Additionally, there are estimated to be over 2,000 crates of AN-M1A1 and/or AN-M4A1 “cluster adapter” type bombs remaining in UK waters in the cargo of a sunken World War II ship off the east coast of England.[19] The UK has not reported any cluster munition contamination in its Article 7 reports.

Extent of contamination

Massive cluster munition remnant contamination (over 1,000km²) exists in one State Party, Lao PDR, and large contamination (between 100–1,000km²) exists in one State Party, Iraq. Three States Parties are believed to have medium contamination (between 10–99km²). Five States Parties, Afghanistan, BiH, Germany, Lebanon, and Somalia have less than 10km² of contamination (see table below).

Estimated area of cluster munition remnants contamination in States Parties

|

Over 1,000km² |

100–1,000km² |

10–99km² |

Less than 10km² |

|

Lao PDR |

Iraq |

Chad |

Afghanistan |

|

Chile |

BiH |

||

|

Mauritania |

Germany* |

||

|

Lebanon |

|||

|

Somalia |

* Germany has reported contamination not exceeding 11km², and has reported 2.8km² cleared, hence the Monitor considers its contamination to be under 10km².

Lao PDR is known to be the most heavily contaminated State Party. Contamination is confirmed to exist in 14 of its 17 provinces, and survey is ongoing in six of the most heavily contaminated provinces. The National Regulatory Authority (NRA) for the unexploded ordnance (UXO) Sector in Lao PDR reported to the Monitor that 1,177.55km² of confirmed hazardous areas (CHA) had been identified by the end of June 2020,[20] and it is expected that a complete picture of CHA in the six provinces will be available by June 2022.[21]

The Regional Mine Action Centre (RMAC) South in Iraq reported to the Monitor that as of the end of 2019, cluster munition remnants covered a total area of 178.64km² in the center and south of the country.[22] Cluster munition remnants are not reported as CHAs in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, although in the past operators have reported clearance of some cluster munition tasks.[23]

In its Article 4 revised deadline extension request of 29 June 2020, Chile stated that the current estimate of contamination in the country is 64.61km². This is a reduction from the original estimate of almost 97km², following the conduct of non-technical survey (NTS) which was completed in 2019.[24] However, Chile has stated that due to the usual procedures of the armed forces, unexploded submunitions may no longer exist,[25] suggesting that the actual area containing cluster munition remnants may be minimal.

Chad’s national mine action center, the National High Commission for Demining (HCND), reported that 55.4km² are contaminated with cluster munition remnants, of which 55.05km² is classified as CHA and 0.35km² as suspected hazardous areas (SHA).[26]

The initial estimate of the new contamination reported in Mauritania is 36km², contaminated with BLU-63, M42 and MK118 submunitions.[27]

Germany has identified evidence of ShOAB-0.5 submunitions on or just below the natural ground surface (not exceeding some 30cm) over an area not exceeding 11km².[28]

The Lebanon Mine Action Centre (LMAC) told the Monitor that as of the end of 2019, cluster munition remnant contamination covers 8.87km² in four areas: Bekaa, Mount Lebanon, and in the north and south of Lebanon.[29] This total includes 0.26km² of new contamination in the northeast of Lebanon, the result of a spillover from the Syrian crisis.[30] In 2018, Lebanon reviewed its recording of polygons and standardized the recording of clearance data within its database, which enabled it to establish a new baseline of 54.77km²,[31] of which almost 84% has now been cleared.[32] Lebanon hopes to have a clear picture of the remaining contamination by the end of 2020.[33] The Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) in Afghanistan has informed the Monitor of seven recorded cluster munition contaminated areas totaling 5.8km² in two provinces at the end of 2019, although it noted that there is some evidence, generated through local requests, of additional cluster munition contamination which requires investigation.[34]

BiH Mine Action Centre (BHMAC) reported to the Monitor that as of December 2019, a total of 2.31km2 of cluster munition contamination remained in nine locations.[35] However, it stated at the Ninth Meeting of States Parties in Geneva in 2019 that 3.6 km2 was “separated” as “non-conventionally contaminated areas” following NTS.[36] Information on the release of this land previously suspected to contain cluster munition contamination by methods other than clearance was not reported in its Article 7 report for 2019, and a report was not submitted for calendar year 2018.[37] BiH did not provide information to the Monitor on land released by NTS for the period 2010–2019. BiH needs to clarify if the area separated from recorded cluster munition contaminated areas is contaminated with unmodified KB-1 and/or KB-2 DPICM scattered individually as single submunitions,[38] or if these are locally-manufactured M93 rifle grenades with modified KB-1 and KB-2 cluster submunitions, which are not covered by the convention.

The extent of contamination in Somalia is unknown but thought to be small.

Cluster munition contamination in signatories

Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Uganda are all signatories to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Uganda completed clearance in 2008.

The extent to which Angola is affected by cluster munition remnants remains unclear. There is no confirmed contamination, but there may remain abandoned cluster munitions or unexploded submunitions. Cluster munition contamination was a result of decades of armed conflict that ended in 2002, although it is unclear when, or by whom, cluster munitions were used. In 2018, 85 submunitions were found and destroyed and in 2019, 164 submunitions were found and destroyed. These were destroyed through explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) callouts rather than clearance.[39]

The DRC is suspected to have some small remaining areas of cluster munition contamination, although the previously known areas have been cleared. Cluster munitions have been used during the conflicts in the DRC and the presence of cluster munition remnants was previously reported in four provinces. Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) cleared the last of these areas in Equateur in April 2017.[40] However, the Congolese Mine Action Center (Centre Congolais de Lutte Antimines, CCLAM) reported to the Monitor in August 2020 that they believed cluster munitions to be present in five provinces, although a survey would need to be conducted to confirm the extent of contamination.[41] The UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) reported two types of cluster munition in the DRC, namely BL755 and PM-1.

Cluster munition contamination in non-signatories and other areas

Thirteen non-signatories and three other areas have, or are believed to have, land containing cluster munitions on their territories: Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Georgia, Iran, Libya, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Vietnam, Yemen, and other areas Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh and Western Sahara (see table below).

The only non-signatory to complete clearance of cluster munitions is Thailand, which reported clearance in 2011.

Estimated area of cluster munition remnants contamination in non-signatories and other areas

|

Over 1,000km² |

100–1,000km² |

10–99km² |

Less than 10km² |

|

Vietnam |

Cambodia |

Azerbaijan |

Georgia |

|

Libya |

Iran |

||

|

Syria |

Serbia |

||

|

Ukraine |

South Sudan |

||

|

Yemen |

Sudan |

||

|

Kosovo |

Tajikistan |

||

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

Western Sahara |

||

Note: Other areas are indicated in italics.

Extent of contamination

The full extent of contamination in many of the non-signatories and other areas is not known. However, Vietnam is believed to have massive cluster munition remnant contamination (over 1,000km²), and Cambodia has large contamination (between 100 – 1,000km²). Contamination in both Vietnam and Cambodia results from intensive bombing by the US during the Vietnam War. Five non-signatories and two other areas are believed to have between 10–99km² of contamination, while six non-signatories and one other area are thought to have less than 10km².

Vietnam is massively contaminated by cluster munition remnants, but no accurate estimate of the extent exists, even to the nearest hundred square kilometers. An explosive remnants of war (ERW) impact survey, which began in 2004 and was completed in 2014, was published in 2018. It found that 61,308km2 or 19% of Vietnam’s land surface area was affected by ERW, but did not specify if the area was affected by cluster munition remnants. However, cluster munition remnants are reported to affect 32 of Vietnam’s 63 provinces and cities.[42] In Quang Tri province, one of the most heavily bombed areas in the country, survey is ongoing and the current estimate of total land contaminated by cluster munitions is 421.32km².[43]

The estimate of the area contaminated by cluster munitions in Cambodia is increasing due to ongoing survey. As of December 2019, the Cambodian Mine Action Authority (CMAA) reported to the Monitor that the extent of cluster munition contamination in Cambodia was 709km² (CHA covering 74km² and SHA covering 635km²).[44] The cluster munition contamination is concentrated in northeastern provinces along the borders with Lao PDR and Vietnam.[45]

Non-signatories believed to have between 10–99km² of contamination include Azerbaijan, Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen, and the areas Kosovo and Nagorno-Karabakh.

Some contamination is believed to remain in Azerbaijan in areas occupied by Armenian forces, but the extent is not known.

Contamination in Libya is a consequence of armed conflict in 2011 and renewed conflict since 2014, which has resulted in widespread explosive ordnance contamination, concentrated in urban areas.[46] The extent of cluster munition remnants contamination is unknown. National authorities have reported that it is limited to a few areas.[47]

Ongoing conflict in Syria has increased all types of explosive hazards in the country. UNMAS reported that the draft 2020 Humanitarian Needs Overview records 11.5 million people living in 2,562 communities reporting explosive hazard contamination in the last two years.[48] The extent of cluster munition remnant contamination in Syria is not known, although in 2019, surveys of explosive hazards and contaminated areas were carried out in 605 different communities in order to inform risk education messaging and to prioritize areas for future surveying, marking and removal of explosive hazards.[49]

Ukraine has reported that unexploded submunitions contaminate the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.[50] The extent of contamination is not yet known.

In 2014, Yemen identified approximately 18km² of suspected cluster munition hazards, but the escalation of armed conflict since March 2015 has increased the extent of cluster munition contamination in northwestern and central Yemen.[51] In the south, with the exception of a few areas where the frontlines have shifted, there is no cluster munition contamination. The UN Development Programme (UNDP), which has established a mine action coordination center in the south of Yemen, has developed a heat map of suspected contamination.[52]

The Kosovo Mine Action Centre (KMAC) reported 14.34km² of cluster munition contamination in 45 affected areas at the end of 2019,[53] and in Nagorno-Karabakh the HALO Trust has reported 70.48km² of cluster munition contamination.[54]

Non-signatories Georgia, Iran, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan and Tajikistan and the area Western Sahara each have less than 10km² of known contamination.

Georgia is believed to be free from cluster munition contamination, with the possible exception of South Ossetia. The extent of contamination in Iran and Sudan is not known but believed to be small.

Serbia reported a total of 2.3km² of contamination at the end of 2019, of which 0.9km² were CHA and 1.4km² were SHA.[55]

South Sudan submitted a voluntary Article 7 report for the year 2019 and reported 6.4km² of land contaminated by cluster munitions.[56] Cluster munitions are reported to be located in the areas of Yei in Central Equatorial state, Mundri in Western Equatorial state, Wau in Western Bar Ghazal state and Maban in Unity state.

Tajikistan reported to the Monitor 1.5km² of cluster munition contamination, all of which were CHA.[57]

For Western Sahara, the Polisario Front's Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) provided a voluntary Mine Ban Treaty Article 7 transparency report covering calendar year 2019 as well as the period of 2014 to 2019, and which provided information on cluster munition contamination. As of February 2020, Western Sahara reported 1.91km² of cluster munition contamination.[58]

The total number of cluster munition casualties for all time, recorded by the Monitor, reached 22,050 as of the end of 2019. This includes both casualties directly resulting from cluster munition attacks and from unexploded remnants. The data begins from the mid-1960s, due to extensive cluster munition attacks by the United States (US) in Southeast Asia, through to the end of 2019.

As many casualties still go unrecorded, a better indicator of the total number of casualties globally over time is roughly 56,000, calculated from various country estimates, with a high-end total of estimates at some 86,000. Some global estimates of cluster munition casualties are as high as 100,000. However, these are based on extrapolations from limited data samples, which may not be representative of national averages or the actual number of casualties.[59] The countries with the highest recorded numbers of cluster munition casualties are Lao PDR (7,755), Syria (3,580), and Iraq (3,070). The total number of casualties recorded in Syria surpassed those recorded for Iraq in 2016.

Thousands of cluster munition casualties from past conflicts have gone unrecorded, particularly casualties that occurred during extensive use in Southeast Asia, Afghanistan and the Middle East (notably in Iraq, where there have been estimates of between 5,500 and 8,000 casualties from cluster munitions since 1991).[60] Before 2008, when the Convention on Cluster Munitions opened for signature, 13,306 recorded cluster munition casualties were identified globally.[61] Since then, the number of recorded casualties has increased due to updated casualty surveys identifying pre-convention casualties, new casualties from pre-convention remnants, as well as new use of cluster munitions during attacks and the remnants they have left behind.

Cluster munition casualties in 2019

The Monitor recorded a total of 286 cluster munition casualties in 2019. These casualties occurred in nine countries, including four States Parties, and two other areas.[62] Civilians accounted for 99% of all casualties whose status was recorded in 2019, as was the case in 2018 and 2017, consistent with statistics on cluster munition casualties for all time due to the indiscriminate and inhumane nature of the weapon.

The total figure for annual casualties in 2019 includes those incurred at the time of attack (221) and from explosive cluster munition remnants (65). The real number of new casualties is likely to be much higher and fluctuations in some years may be due to variations in the availability of information and data at country level.

Cluster munition casualties in 2019

|

Cluster munition attacks casualties |

|

|

Syria |

219 |

|

Libya |

2 |

|

Cluster munition remnants casualties |

|

|

Iraq |

20 |

|

Syria |

13 |

|

Yemen |

9 |

|

Afghanistan |

5 |

|

Lao PDR |

5 |

|

Lebanon |

5 |

|

Serbia |

3 |

|

South Sudan |

3 |

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

1 |

|

Western Sahara |

1 |

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold, other areas in italics.

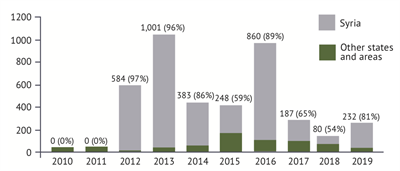

The 2019 total marks an increase from the total of 149 casualties recorded in 2018, which was the lowest annual global casualty figure since 2012 when the Monitor started recording cluster munition casualties from new use in Syria. The 2019 total is almost equivalent to the 289 casualties recorded in 2017, which marked a significant drop from the 971 cluster munition casualties recorded in 2016.

Overall, in 2019, 221 people were recorded killed or injured directly due to cluster munition attacks in Libya and Syria. This is an increase on the 65 casualties recorded in Syria in 2018, and the 196 casualties recorded in total due to attacks in Syria and Yemen in 2017. In 2016 and 2017, the only casualties from cluster munition attacks were recorded in Syria and Yemen.

As has been the case for each year since 2012, the majority of annual cluster munition casualties in 2019 were recorded in Syria.[63] Overall, since 2012, 81% of all cluster munition casualties globally were recorded in Syria.

Cluster munition casualties in Syria and in all other states and areas 2010–2019

Note: Numbers at the top of each bar indicate the total number of casualties in Syria.

Cluster munition casualties in States Parties and signatories

Since 2010, new cluster munition remnant casualties were also recorded in seven States Parties: Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon; and in signatory, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

In State Party Lao PDR, the world’s most cluster munition-affected state, the number of submunition casualties continued to decrease from the 10-year high of 51 recorded in 2016 to five in 2019. Another 10 casualties in 2019 may have been due to unexploded submunitions, but the explosive item involved in each of those cases could not be adequately determined.

In 2017, in an account of the long-term humanitarian impacts of cluster munitions recorded during the reporting period, a 10-year-old girl picked up a submunition, known in Lao PDR as a “bombie,” while walking to school in the northern province of Xieng Khouang. Thinking it was a toy, she took it to her home where it exploded, killing her and injuring another 11 people, including eight children—the youngest being three years old.[64]

The majority of all recorded cluster munition casualties for all time, 59%, occurred in States Parties. Casualties directly caused by attacks before the convention in States Parties have been grossly under-recorded, with no data or estimate available for Lao PDR, the most heavily bombed country.

States Parties where cluster munition casualties have occurred (data for all time, as of 31 December 2019)[65]

|

State Party |

Attacks |

Remnants |

Unknown |

Total |

|

Lao PDR |

Unknown |

7,755 |

0 |

7,755 |

|

Iraq |

388 |

2,682 |

0 |

3,070 |

|

Afghanistan |

25 |

760 |

0 |

785 |

|

Lebanon |

16 |

734 |

0 |

750 |

|

Croatia |

207 |

37 |

0 |

244 |

|

BiH |

86 |

145 |

0 |

231 |

|

Albania |

2 |

53 |

0 |

55 |

|

Colombia |

44 |

0 |

0 |

44 |

|

Sierra Leone |

28 |

0 |

0 |

28 |

|

Montenegro |

4 |

4 |

1 |

9 |

|

Chad |

Unknown |

4 |

0 |

4 |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Mozambique |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Somalia |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

A total of 604 casualties have been recorded in signatory states.[66]

Signatories where cluster munition casualties have occurred (all time, as of 31 December 2019)

|

Angola |

|

DRC |

|

Liberia |

|

Uganda |

Data collection for casualties and victim assistance

Article 5 of the convention requires that States Parties with victims make “every effort to collect reliable relevant data” and assess the needs of cluster munition victims. The Dubrovnik Action Plan commits States Parties to the ongoing assessment of those needs. Although data is collected on casualties, often little is known or reported about the actual number of families and communities affected by cluster munitions, who are also victims by definition. Available information indicates that their needs are likely to be extensive.

Afghanistan was finalizing a national health and disability information system, and in a related project, was registering persons with war-related disabilities to provide them with pensions.[67] In Lao PDR, the National Regulatory Authority (NRA) Survivor Tracking System, a system for collecting data on new casualties, is designed to provide an ongoing survey of all survivors’ needs.[68] In 2019, data on services provided was available through the NRA online Operations Dashboard.[69] BiH continued to report that further survey was needed to establish detailed information on cluster munition victims, specifically those who had already been identified through initial survey. Both Croatia and Lebanon needed to revise or combine their national victim databases, and a much-delayed victim survey in Croatia was expected to start in the first half of 2020.[70] The Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) completed the first phase of a national needs assessment of mine/explosive remnants of war (ERW) and cluster munition victims, in 2010, prior to the convention’s entry into force for the country.[71] In 2013, LMAC, along with the UN Development Programme (UNDP), launched a survey focused on 690 victims (survivors and deceased) and their families.[72]

A mine/ERW victim census was planned to be conducted in Chad in order to update the national database.[73] Further survey was needed in order to identify cluster munition victims and/or needs in Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Montenegro, and Sierra Leone. Mauritania and Zambia had yet to conduct initial surveys to identify or confirm if they have cluster munition victims.

Cluster munition casualties in non-signatory states and other areas

In non-signatory states and areas, 8,471 cluster munition casualties have been recorded for all time. This data includes countries that remain affected long after the attacks took place, such as Cambodia and Vietnam ; as well as those that have had new casualties due to more recent attacks occurring since entry into force of the convention in Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen.

Data was often severely lacking for casualties that were killed and injured during cluster munition attacks, including those among military personnel and other direct participants in conflict, such as combatants in non-state armed groups and militias. However, since 2010, recording of the impact of cluster munition attacks has improved significantly, and casualties recorded from attacks have outnumbered those due to cluster munition remnants. Of all recorded casualties which occurred during cluster munition attacks for all countries and areas for all time (4,514), just under half (2,102) of those casualties were reported in Syria since 2012.

Since 2010, cluster munition remnant casualties have occurred in eight non-signatory states: Cambodia, Libya, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Ukraine, Vietnam, and Yemen; and three other areas: Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara.

Non-signatories where cluster munition casualties have occurred (all time, as of 31 December 2019)

|

Cambodia |

Israel |

Serbia |

Tajikistan |

|

Eritrea |

Kuwait |

South Sudan |

Ukraine |

|

Ethiopia |

Libya |

Sudan |

Vietnam |

|

Georgia |

Russia |

Syria |

Yemen |

Other areas where cluster munition casualties have occurred (all time as of 31 December 2019)

|

Kosovo |

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

|

Western Sahara |

Clearance coordination

In 2019, clearance programs in eight States Parties with remaining contamination, Afghanistan, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia, were coordinated through national mine action centers. The Ministry of National Defense is responsible for overseeing mine action in Chile, and the Federal Ministry of Defense in Germany is similarly responsible for overseeing clearance activities.

The Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) in Afghanistan took over full management of the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan from the UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) as of 1June 2019, although UNMAS and the United States (US) continue to financially support DMAC.[74]

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia had a mine action strategy or plan in place in 2019, but not all included reference to cluster munition contamination and clearance. Chile had a plan for the execution of demining activities for the year 2019, but still needs to develop a full plan or strategy for the clearance of cluster munitions in its extension request.[75] The Lao PDR strategy, “The Safe Path Forward” was reviewed in 2015, and its 2019 Article 4 Extension Request provided a workplan for the period August 2020–July 2025.[76]

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia had national standards in place which are consistent with the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS), although the standards in Chad and Somalia do not include cluster munition remnant clearance and survey. Chile uses IMAS and a Joint Demining Manual for its Armed Forces, and clearance and survey in Germany are conducted according to German federal legislation.

Seven of these States Parties[77] use the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA), including Chile. BiH has its own database, with a specific database for cluster munition contamination (CM BHMAC). BiH Mine Action Center (BHMAC) reported that this database needs to be updated.[78] Germany uses its own information management system.[79]

Risk education coordination

In 2019, 10 States Parties had institutions in place for coordinating risk education, namely Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Chile, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia. In most cases the risk education program is coordinated by the mine action center, although for the school-based programs in Chile, Iraq, and Lao PDR, the Ministry of Education takes on a coordination role. In Croatia, the Civil Protection Directorate was responsible for risk education. Regular risk education meetings took place in 2019 in States Parties Afghanistan, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon. Chad and Somalia reported risk education matters were discussed during mine action coordination meetings.[80]

Risk education strategies are included within the national mine action strategies of Afghanistan, BiH, and Lao PDR. Lebanon had a national-level risk education curriculum to guide implementation.[81]

Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon all have national standards for risk education. In 2019, Lebanon reported the revision of national standards for risk education.[82] Afghanistan reported a comprehensive clean-up of risk education data in 2019, including classifying risk education programs and activity types, and developing guidelines for quality management inspectors.[83]

Involvement of victims in coordination

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions have committed to actively include cluster munition victims and their representative organizations in policy- and decision-making, so that their participation is made sustainable and meaningful.

In most States Parties to the convention, survivors were engaged in relevant activities, but generally there was no indication that survivors’ views were actively considered or acted upon.

In BiH, a victim assistance coordination body was officially established on 23 May 2018. Survivors’ representatives were involved in the two unofficial coordination meetings held in 2019 and advocated for official coordination. Somalia held survivor assistance meetings in early 2019. Coordination began again some five years after the first and only previous coordination meeting on victim assistance in Somalia, held in 2014. Croatia has not held any victim assistance coordination meetings in recent years. Montenegro and Sierra Leone were the only states where the Monitor has not identified any survivor involvement in victim assistance activities since entry into force of the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Nevertheless, disabled peoples’ organizations (DPOs) in both countries advocated for the rights of all persons with disabilities. The Sierra Leone Union on Disability Issues (SLUDI) requested the official state appointment of persons with disabilities to high-level governance positions where they can influence decisions that affect them and counter existing marginalization and discrimination at all levels.

Victim assistance planning

Among States Parties with cluster munition victims, only Sierra Leone did not have a designated victim assistance focal point, which was an action set forth in the Dubrovnik Action Plan with the deadline of the end of 2016.

Through the Dubrovnik Action Plan, States Parties without a national disability action plan committed to draft a disability or victim assistance plan before the end of 2018.

As of the end of 2019, six States Parties had current planning in place for victim assistance: Albania, BiH, Colombia, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mozambique. Mozambique has not reported on implementation of its specific victim assistance planning and has remained focused on the earlier broad national disability plan, which also includes references to victim assistance. Chad has not yet adopted a revised plan, while Somalia has developed a draft plan that was launched at the end of 2019. Afghanistan developed a new national disability strategy. This was the first draft to be completed since the previous strategy for 2008–2011 expired, which was before Afghanistan became a State Party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions in March 2012. Afghanistan’s draft strategy was under review in 2019.[84] Iraq was using annually updated plans, but in 2018 began the process of developing a national victim assistance and disability strategy with the Mine Ban Treaty Implementation Support Unit and European Union (EU) funding. Croatia has not replaced its plan that expired in 2014. Montenegro and Sierra Leone did not have an active victim assistance plan in place but did have disability-related activities coordinated at the national-level.

Mine action management and coordination

|

State Party |

Coordination mechanism |

Clearance strategy |

Risk education coordination |

Risk education strategy |

Victim assistance plan |

|

|

Afghanistan |

DMAC |

Strategy 2016–2020 Workplan 2013–2023 |

DMAC through a RE TWG |

Included in Mine Action strategy |

National disability strategy (draft under review) |

|

|

BiH |

BHMAC |

Strategy 2019–2025 |

BHMAC |

Sub-strategy for risk education 2009–2019 |

New victim assistance strategy being drafted |

|

|

Chad |

National Mine Action Authority in Chad (HCND) |

National Mine Action Plan 2014–2019 |

HCND |

No current strategy |

No current plan |

|

|

Chile |

Ministry of Defense (MoD) |

Partial |

MoD in coordination with Ministry of Education |

N/R |

No current plan |

|

|

Croatia |

Ministry of the Interior/Civil Protection Directorate (Croatian Mine Action Center is a department) |

Revised National Mine Action Strategy for 2020–2026 |

Ministry of the Interior, through the Civil Protection Directorate and Police Directorate |

N/R |

No current plan |

|

|

Germany |

MoD |

Yes |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

|

Iraq |

Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) & Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA) |

Prioritization Strategy |

DMA and Ministry of Education |

N/R |

Plan drafted and adopted |

|

|

Lao PDR |

National Regulatory Authority for the UXO Sector (NRA) |

Safe Path Forward 2016–2020 |

NRA through a RE TWG and Ministry of Education |

Sub-section on RE in UXO sector strategy |

UXO/mine Victim Assistance Strategy 2014–2020 |

|

|

Lebanon |

Lebanon Mine Action Centre (LMAC) |

Strategy 2020–2025 |

LMAC through RE Steering Committee |

RE Curriculum |

2011–2020 National Mine Action Strategy |

|

|

Mauritania |

National Humanitarian Demining Programme for Development (PNDHD) |

No strategy |

PNDHD |

No strategy |

No plan |

|

|

Montenegro |

Directorate for Emergency Situations, Ministry of Interior |

No strategy |

N/A |

N/A |

Integrated in state planning |

|

|

Sierra Leone |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Disability planning |

|

|

Somalia |

Somali Explosive Management Authority (SEMA) |

Strategy 2018–2020 |

SEMA |

No strategy |

Draft plan launched in November 2019 |

|

Note: N/A=not applicable; N/R=not reported; RE=risk education; TWG=technical working group.

Regional cooperation

During 2019, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Mine Action Centre (ARMAC)–operational since 2018–implemented a project to “Enhance Awareness Programmes on the Dangers of Mines/Explosive Remnants of War [ERW] among ASEAN members states.” The project involved research and consultative meetings on risk education between July and September 2019 in the five ASEAN states affected by mines and ERW, including State Party Lao PDR, and non-signatories Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam. An ARMAC side-event was held in November 2019 at the Fourth Review Conference of the Mine Ban Treaty in Oslo, and a regional consultative meeting with all ASEAN state members was held in Siem Reap, Cambodia on 6 February 2020 to finalize the study.[85] Phase 2 of the project will involve the implementation of the study recommendations for an integrated approach[86] to risk education in projects in the region.[87]

ARMAC also has responsibility to support victim assistance in the region and during 2019 was in the development phase of establishing a regional platform to promote experience, knowledge, expertise and exchange on victim assistance among ASEAN member states.[88]

In Europe, the South-Eastern Europe Mine Action Coordination Council (SEEMACC) was established through the agreement of the directors of mine action centers in Albania, BiH, Croatia, and ITF Enhancing Human Security.[89] In 2020–2021 SEEMACC will implement a project to support regional capacity through the development of criteria for training and implementation of humanitarian demining, victim assistance and risk education.[90]

The UN Development Programme (UNDP) in Lebanon, in coordination with the Norwegian Embassy, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and LMAC, was developing a project focusing on support to reduce risk for Syrian refugees in Lebanon in the prospect of their return home.[91]

Cluster Munition Remnants Clearance

Clearance in 2019

In 2019, approximately 82km² of cluster munition contaminated land was cleared by States Parties, an increase from 76km² cleared in 2018. At least 96,533 submunitions were cleared and destroyed in 2019.

About 78% of this area clearance was undertaken in Lao PDR, which cleared a total of 64.95km², including 46.42km² of agricultural land and 18.53km² for development.[92] This was an increase of 2.88km² from the previous year. The number of cluster munition remnants destroyed in Lao PDR also increased in 2019, with a total of 80,247 submunitions destroyed, an increase from the 78,974 recorded in 2018.[93] Lao PDR requested and received a five-year extension to its Article 4 deadline in 2019.

Croatia completed clearance of cluster munitions in July 2020. It cleared 0.04km² in 2019. Since 2010 until the end of 2019, Croatia reported the release of 5.28km2, with a remaining 0.03km² to be cleared during 2020. Throughout the 10-year period, Croatia reported having cleared and destroyed more than 3,100 cluster munition remnants.[94]

Montenegro declared completion of clearance of all cluster munitions in July 2020. No clearance was reported in 2013–2017. In 2018, 0.01km² was cleared with six submunitions destroyed. In 2019, 0.78km² was cleared with 64 submunitions destroyed.[95] In its most recent Article 7 transparency report covering calendar year 2019, Montenegro stated that the size of the remaining contaminated area in the country was 1.72km², which suggests that the remaining 0.93km² of contaminated land was released in the first half of 2020.

Iraq reported to the Monitor clearance of 6.29km² of cluster munition contaminated land in 2019 and the removal of 9,996 submunitions, which was a decrease in the amount of land cleared compared to 2018, but an increase in the number of submunitions cleared.[96]

Chad has conducted limited survey in the past. Chad reported the clearance of 4.33km² in 2019. Eighteen submunitions were found during clearance and destroyed.[97]

Afghanistan reported to the Monitor that 2.72km² of cluster munition contaminated land was cleared in 2019 with 86 submunitions destroyed.[98] This is a decrease from the 4.2km² cleared in 2018, when 217 submunitions were destroyed.[99]

Lebanon reported 1.26 km² of clearance in 2019.[100] This was an increase from its 2018 figure of 1.14km² cleared. A total of 4,037 submunitions were cleared and destroyed in 2019. Lebanon requested a five-year extension to its Article 4 deadline in 2020.

Germany only began clearance in 2017, six years after it reported contamination. Germany requested an extension to its Article 4 deadline in 2019. Germany has a time-bound plan that estimates the clearance of 1.5–2km² (150–200 hectares) per year, with completion likely by 2024.[101] Germany reported that it cleared 2.8km² between 2017 and 2019,[102] which means that its current clearance is below its projected output.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) reported clearing 0.72km² of contaminated land in 2019.[103] No Article 7 report was submitted by BiH for calendar year 2018. BiH’s 2018 annual report on mine action produced by BiH Mine Action Centre (BHMAC) stated that 0.28km² was cleared in 2018 and 1,009 submunitions were destroyed.[104] In 2019, BiH reported a further 3.6km² was “separated” from the total recorded cluster munition contamination during non-technical survey (NTS) due to it being considered “non-conventionally contaminated.”[105] It was not reported to what extent previous clearance occurred in these areas.

Chile prioritized the clearance of landmines over the clearance of cluster munitions[106] and has not yet conducted any clearance of cluster munition remnants, despite having become a State Party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions in December 2010. Chile requested an extension for clearance of cluster munitions in January 2020. While no clearance took place in 2019, it was reported that NTS of the areas was completed, reducing the reported 96.88m², by 32.27m², and leaving the remaining suspected area at 64.61km².[107]

Somalia reported six contaminated areas on its historical database and there have been reports of munitions in Southwest State, Jubaland State and Puntland, However, no clearance or survey has been reported.[108]

Mauritania, which announced new unreported contamination in 2019, has yet to conduct survey or clearance.

Cluster munition remnants clearance in 2018–2019[109]

|

State Party |

2018 |

2019 |

||

|

Clearance (km²) |

CMR destroyed |

Clearance (km²) |

CMR destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

4.2 |

217 |

2.72 |

86 |

|

BiH |

0.28 |

1,009 |

0.72 |

85 |

|

Chad |

0 |

0 |

4.33 |

18* |

|

Chile |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Croatia |

0.86 |

571 |

0.04 |

186 |

|

Germany |

0.98 |

1,537 |

1.35 |

1,814 |

|

Iraq |

7.16 |

3,743 |

6.29 |

9,996 |

|

Lao PDR |

62.07 |

78,974** |

64.95 |

80,247*** |

|

Lebanon |

1.14 |

3,583 |

1.26 |

4,037 |

|

Mauritania |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Montenegro |

0.01 |

6 |

0.78 |

64 |

|

Somalia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

TOTAL |

76.70 |

89,640 |

82.44 |

96,533 |

Note: CMR=cluster munition remnants; ERW=explosive remnants of war.

* Reported 21 containers but not specified if loaded.

** Total ERW destroyed: 97,624, including 31 mines, 148 big bombs, and 18,471 other ERW.

*** Total ERW destroyed: 101,512, including 40 mines, 170 big bombs, and 21,055 other ERW.

Clearance 2010–2019

In the 10 years since the signing of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, almost 560km² of land has been cleared in States Parties, with at least 452,938 submunitions cleared and destroyed.[110] State Party Lao PDR has cleared the most amount of land (80% of the total) and destroyed the greatest number of submunitions (79% of the total) during the 10-year period. Chile has yet to clear any land of cluster munition remnants.

Cluster munition remnants clearance in 2010–2019[111]

|

State Party |

2010–2019 |

|

|

Clearance (km²) |

CMR destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

9.74 |

315 |

|

BiH |

2.37 |

2,718 |

|

Chad |

4.33 |

18 |

|

Chile |

0 |

0 |

|

Croatia |

5.28 |

3,100 |

|

Germany |

2.80 |

3,864 |

|

Iraq |

68.44 |

49,704 |

|

Lao PDR |

448.63 |

357,846 |

|

Lebanon |

14.87 |

34,063 |

|

Mauritania |

1.96 |

1,246 |

|

Montenegro |

0.79 |

64 |

|

Somalia |

0 |

0 |

|

TOTAL |

559.21 |

452,938 |

Note: CMR=cluster munition remnants.

Article 4 deadlines and extension requests

If a State Party believes that it will be unable to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants within 10 years after the entry into force of the convention for the State Party, it is able to request an extension of its deadline for a period of up to five years.

The first extension requests were submitted for consideration for the Ninth Meeting of States Parties in Geneva in September 2019. In 2019, two countries, Germany and Lao PDR, asked and were granted a full five-year extension to their Article 4 deadlines. In 2020, BiH, Lebanon, and Chile have submitted requests (see table below).

Status of Article 4 progress to completion

|

State Party |

Original deadline |

Extension Request |

Current deadline |

Expectation to meet deadline |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2022 |

N/A |

1 March 2022 |

Uncertain |

|

BiH |

1 March 2021 |

Submitted in 2020 |

1 March 2021 |

Expects to complete in 2023 |

|

Chad |

1 September 2023 |

N/A |

1 September 2023 |

Expects to complete before 2023 |

|

Chile |

1 June 2021 |

Submitted in 2020 |

1 June 2021 |

Expects to complete end 2025 |

|

Germany |

1 August 2020 |

Granted in 2019 (5 years) |

1 August 2025 |

Expects to complete end 2024* |

|

Iraq |

1 November 2023 |

N/A |

1 November 2023 |

Unlikely to meet deadline |

|

Lao PDR |

1 August 2020 |

Granted in 2019 (5 years) |

1 August 2025 |

Unlikely to meet deadline |

|

Lebanon |

1 May 2021 |

Submitted in 2020 |

1 May 2021 |

Expects to complete by 2025 |

|

Mauritania |

1 August 2022 |

N/A |

1 August 2022 |

Unknown** |

|

Somalia |

1 March 2026 |

N/A |

1 March 2026 |

Unknown |

Note: N/A=not applicable.

* Clearance is expected to be completed at the end of 2024, with final reporting and documentation completed in 2025.

** Mauritania completed in 2013 but has since reported finding new cluster munition remnants contamination.

Two States Parties—Chad and Germany—are expected to meet their Article 4 deadlines.

Chad’s Article 7 report for the year 2019, provides a workplan for the period 2020–2021, which suggests clearance will be completed in 2021.[112]

Germany requested a five-year extension until August 2025 to clear a former military training area at Wittstock. In its request, Germany stated that it should be able to conclude this work by 2024.[113]

For most of the States Parties, it is uncertain or unlikely that they will meet their current deadlines, despite several States Parties having relatively small areas of contamination remaining, such as Afghanistan, BiH, Lebanon, and Somalia.

Afghanistan told the Monitor that it is uncertain whether it will meet its current deadline of 1 March 2022.[114] Funding for the clearance of the seven remaining areas had been pledged by the United States (US), but Afghanistan has stated that there is evidence of more cluster munition contamination that needs assessment and survey. Ongoing conflict between the government, the Taliban and other non-state armed groups is continuing to add to the explosive remnants of war (ERW) contamination in Afghanistan, particularly improvised mines, which have overtaken legacy mined areas as the largest humanitarian threat.[115] Competing priorities make it challenging for Afghanistan to address the contamination.

Iraq told the Monitor that it is unlikely to meet its deadline of 2023, and that with its current capacity the clearance would require 17 more years. To clear within the deadline, Iraq reports that it would need a capacity of 45 teams.[116]

In Lao PDR, given the size of the known contamination, the remaining challenge is enormous. At the current annual clearance rate of 50km² per year,[117] the Monitor estimates that Lao PDR will need at least 23 years from 2020 to complete the clearance of the known cluster munitions in its territory. Lao PDR has indicated that completion of survey will be one of the priorities of work during the extension period, with the expectation that additional international support will be needed.[118] In September 2016, Lao PDR launched Sustainable Development Goal 18 (SDG-18), with a 2030 target to reduce the number of unexploded ordnance (UXO) casualties to zero; to clear all UXO contamination from high priority areas and villages; to improve health and livelihood needs of victims; and to ensure government funding for remaining UXO activities.[119] This is indicative of both the impact of cluster munition contamination on the development of Lao PDR and the country’s commitment to address the contamination and its impacts.

BiH, Chile, and Lebanon both submitted new extension requests in 2020 and requested full five-year extension periods.

BiH told the Monitor that it expects to complete cluster munition clearance by 2023, two years after its current Article 4 deadline of 1 March 2021.[120] An extension request was submitted in September 2020.

Chile failed to conduct any clearance of its cluster munitions over the last 10 years due to prioritizing mine clearance[121] (which it completed in February 2020).[122] In January 2020, Chile submitted an extension request for a period of five years.[123] Chile states that the Chilean Armed Forces are scheduled to carry out the clean-up within five years and that financial planning also stipulates a five-year term.[124] As part of the extension request, Chile requested international assistance of US$1.6 million for demining equipment and the undertaking of risk education in four locations for the period 2021–2026.[125] A revised extension request was submitted on 29 June 2020.

While Lebanon has reported clearance of 84% of its cluster munition contaminated land, it is unlikely to complete the remaining 16% by its current deadline due to challenges such as the discovery of further contamination, difficult terrain, extreme weather conditions and lack of financial assistance.[126] Lebanon has estimated that if it secures the same funds as in the last three years and the Government of Lebanon meets its declared contribution for the first three years of the extension, then it will be able to complete the clearance of cluster munitions by 2025.[127]

It is unknown whether Somalia will meet its clearance deadline of 1 March 2026.

Mauritania has yet to submit details of clearance plans for the estimated 36km² of newly-found contaminated area.

Obligations regarding risk education

The Convention on Cluster Munitions Article 4, Paragraph 2, states that each State Party shall “conduct risk reduction education to ensure awareness among civilians living in or around cluster munition contaminated areas of the risks posed by such remnants.”

Risk education in the context of the convention encompasses interventions aimed to protect civilian populations and individual civilians at the time of use of cluster munitions, when they fail to function as intended (remnants), or when they have been abandoned. Action 3.2 of the Dubrovnik Action Plan further highlights the need for risk education programs to be sensitized to age, gender and ethnic considerations and based on an assessment of need and vulnerability and an understanding of risk-taking behavior.[128]

States Parties are required to report on the measures taken to provide risk education and to ensure an immediate and effective warning to civilians living in cluster munition contaminated areas under their jurisdiction or control. This includes perimeter-marking of cluster munition contaminated areas, the provision of warning signs, and the marking of suspected hazardous areas.

Reporting

Since the First Review Conference in 2015, only five States Parties, Afghanistan, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon, with outstanding Article 4 obligations have provided detailed information on risk education efforts. Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, Mauritania, Montenegro, and Somalia have provided limited information regarding risk education. Chile and Germany have also provided limited information due to their contamination being confined to armed forces training areas.

Only Iraq and Lao PDR provided beneficiary numbers disaggregated by age and sex in their Article 7 transparency reports for the year 2019. Lebanon provided beneficiary numbers disaggregated by sex but not age.

Provision of risk education

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon all report conducting risk education which includes cluster munition remnants.

In State Party Lao PDR, where cluster munition contamination is the predominant type of unexploded ordnance (UXO) contamination, risk education is specifically directed to addressing the risk behaviors associated with cluster munition remnants.

In other States Parties where cluster munition remnant contamination is mixed with other forms of contamination which may be more predominant, risk education operators do not conduct specific sessions for cluster munition remnants. Afghanistan reported that risk education covers risks posed by all types of ordnance, including cluster munitions, although only two communities in two districts are directly affected by the seven known contaminated areas.[129] BiH also reported that mine/UXO risk education includes cluster munitions.[130]

Regional Mine Action Centre (RMAC) South in Iraq reported to the Monitor that information about cluster munitions was included as part of risk education sessions addressing all explosive remnants of war (ERW), but in areas closer to cluster munition contamination, more emphasis was placed on the risk behaviors with submunitions that led to casualties.[131] In the Kurdistan region of Iraq, cluster munition contamination is included as one type of contamination among others, or is not addressed as it is seen to be less of an issue.[132]

In Lebanon, some operators report including cluster munitions within their risk education, while others do not.

In States Parties Germany and Chile, cluster munition remnant contamination is confined to training ranges belonging to the armed forces. These areas are reported to be perimeter-marked with access prohibited to unauthorized persons.[133] Chile has focused on the conduct of risk education for landmines, although it has stated that cluster munitions are included within the sessions.[134] Germany has, as a precautionary and safeguarding measure, issued an official directive constraining access to the former military training area.[135]

Croatia reported in 2019 that risk education was provided throughout the 10-year period, with more than 140,000 persons reached. The last unexploded submunition casualties were reported in 2013.

Target areas, risk groups and behaviors

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Iraq, and Lebanon have provided risk education for cluster munitions in both rural and urban areas. In Croatia, risk education was conducted in 2019 through public campaigns at city and municipal level concerning contamination in more remote areas.[136] Risk education in Lao PDR is provided predominantly in remote rural areas in the north and in provinces bordering Vietnam and along the former route of the Ho Chi Minh trail. In Afghanistan, Iraq and Lebanon, risk education is also conducted in camps for internally displaced people (IDPs) and refugees.

National-level Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) victim data is used in Afghanistan, Lao PDR, and Lebanon to inform the targeting of risk education. Afghanistan reported to the Monitor that it also maintained a priority scoring matrix to enable it to prioritize the most affected populations in terms of their proximity to the hazards, the number of recent casualties, and incidences of armed conflict.[137] In BiH and Iraq, it was reported that victim databases are incomplete, and in the case of Iraq, not openly available for interrogation.[138]

All States Parties that report on risk education cited children as a key risk group with regards to cluster munition remnants because they are often growing up in contaminated areas, lack knowledge of the risks, and are prone to picking up and playing with items. In Lao PDR, children are known to be tempted to pick up and play with submunitions because of their size and shape.[139]

Adult men and male adolescents are reported to be particularly high-risk groups in relation to cluster munition contamination due to their engagement in livelihood activities which increase the possibility of exposure to cluster munition remnants. In Afghanistan, BiH, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon, high-risk activities in rural areas include cultivation, collection of forest products, hunting and fishing, foraging, and tending animals. Activities such as digging, plowing or burning land are considered high-risk agricultural activities. In urban areas, particularly in Iraq, high-risk activities include construction work and street cleaning.

In Afghanistan, while cluster munition remnants affect fewer people, they are reported to block access to grazing and agricultural land. Migrant workers were reported to be a high-risk group in BiH due to their lack of understanding and knowledge of marking signs and indications of contamination.[140] Seasonal workers and cross-border workers were reported to be a target group in Lebanon.[141] In Croatia, target groups included members of hunting associations, the Croatian mountain rescue service, hikers, farmers and tourists.[142]

In Lao PDR it was reported that men often enter contaminated areas knowingly because of economic necessity. In some contexts, familiarity with contamination means that men will often move ordnance when they encounter them.[143] The Lebanon Mine Action Centre (LMAC) reported that farmers in the south of the country handled and moved ordnance.[144]

The collection of scrap metal and explosives is a risk activity that is recorded in both rural and urban areas. Scrap metal collection has been a common practice in Lao PDR for income generation, and is still reported in some areas, such as in the north of the country.[145] The deliberate engagement with ERW and submunitions for income generation is also reported in other States Parties, including Afghanistan.[146]

In Lao PDR it was reported to the Monitor that teenagers as a group were potentially excluded from risk education activities and that there needs to be more innovation to reach these groups as they may be particularly at risk, especially boys.[147]

Nomadic and pastoral communities were target groups for risk education in States Parties Iraq, Mauritania, and Somalia. While the extent of cluster munition contamination along the Somali border with Ethiopia is not known, in 2014, Somalia claimed it posed an ongoing threat to the lives of nomadic people and their animals.[148] However, Somalia does not report conducting risk education for cluster munition contamination.[149] Mauritania reported providing risk education to nomadic populations across the country and in areas close to suspected or confirmed hazardous areas.[150] RMAC South in Iraq reported providing risk education to nomadic Badia populations and targeting them during pastoral seasons when they gather in grassland areas with their livestock.[151]

In Lao PDR, the Hmong and other ethnic groups were potentially exposed to accidents because they practice “slash and burn” (or swidden) agriculture on a rotational basis.[152] The challenge of providing risk education to ethnic groups speaking different languages and dialects was also reported in State Party Lao PDR.[153]

IDPs and returnees were noted as risk groups in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Lebanon. In areas where people have been displaced due to conflict, such as in State Party Afghanistan, men were reported as often being the first to return to an area affected by conflict before other family members. In Lebanon, which hosts over 1.5 million Syrian refugees, risk education is provided to refugees to sensitize them to the contamination in Lebanon.[154]

Humanity & Inclusion (HI) reported risk education projects that targeted people with disabilities or were integrated into victim assistance projects.[155] In Afghanistan, the HI Mobile Team Project incorporated physical rehabilitation, psychosocial support and risk education for IDPs, returnees and host communities. Risk education teams provided sessions in rehabilitation centers for victims of explosive ordnance and other people with disabilities.[156]

In 2019, risk education was provided to people in emergency situations in Lao PDR and Lebanon. Lao PDR provided emergency risk education for villagers affected by flooding in Attapeu province,[157] and Lebanon provided emergency risk education with UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) support in the north of the country near the Syrian border after a flood.[158] In 2020, it was reported that Lao PDR would receive funding from Turkey as part of the Turkey-UNDP Partnership for Development Programme, to develop a project on strengthening early warning systems and risk education.[159]

Risk education delivery methods

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon reported that risk education is carried out as an integrated part of survey and clearance activities. In cluster munition contaminated areas this is often crucial to support spot task reporting.[160]

Several States Parties also have organizations conducting standalone risk education, for example in BiH.

In Lao PDR, risk education is integrated into the school curriculum at primary level and is in the development phase at secondary level. Lebanon implements risk education activities in educational institutions across Lebanon as part of the school health curriculum.[161] In 2019, LMAC and the Ministry of Education launched training of trainers courses for the Health and Safety teachers, with the aim to cover the entire public school system throughout Lebanon.[162] In Afghanistan, key risk education messages are included for grades 2 to 12, and in BiH and Iraq risk education is provided in schools, but not as part of the curriculum.[163]

The Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) in Afghanistan reported introducing child-focused risk education materials that have been piloted and will be used in field operations. They see it as a significant step towards employing engaging content that will help to change the behavior of children and young adults.[164]

Risk education in Afghanistan and BiH has been integrated into humanitarian and protection sectors. In BiH this is done through the work of the Red Cross, and in Afghanistan risk education has been provided for returnees through the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and at International Organization for Migration (IOM) encashment and transit centers.[165] Lebanon also reports training non-government organization (NGO) activists, social workers and health workers to deliver risk education.[166] HI in Lao PDR reported integrating risk education with the work of its rural development partners, GRET and OXFAM.[167]

Lao PDR, with its long-term cluster munition problem, has developed community-based approaches for risk education through a village volunteer network supported by UXO Lao, and through activities with the Lao Youth Union.[168] Lebanon conducted risk education through youth and scout leaders and LMAC also trained risk education focal points from the Ministry of Tourism in 2019.[169]

Mauritania conducted two prevention campaigns in 2019 as part of the National Humanitarian Demining Program for Development.[170] The risk education was conducted through administrative authorities, teachers, internal security forces (police and gendarmerie), and the army.

Marking

The marking of areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants varies. Lao PDR reported that UXO marking signs are only used for targeted project areas.[171]

BiH reported placing emergency marking signs around suspected areas.[172] Lebanon has fenced and marked dangerous areas, uses warning signs and partners with local communities and authorities to ensure community awareness of contaminated areas.[173] Croatia reported marking hazardous areas and providing maps of the location of hazardous areas to the local authorities and police administration.[174]

In Chile and Germany, all cluster munition remnant contaminated areas were reported as being perimeter fenced and marked to International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) using signs and barbed wire. [175]

The Convention on Cluster Munitions requires that States Parties assist all cluster munition victims in the areas under their jurisdiction. Compliance with victim assistance obligations included in the convention is compulsory, requiring States Parties with cluster munition victims to implement victim assistance activities. Specific activities to ensure that adequate assistance is provided, include the following:[176]

• Collect relevant data and assess the needs of cluster munition victims;

• Coordinate victim assistance programs and develop a national plan;

• Actively involve cluster munition victims in all processes that affect them;

• Ensure adequate, available, and accessible assistance;

• Provide assistance that is gender- and age-sensitive as well as non-discriminatory;[177] and

• Report on progress.

Among the 14 States Parties which have had cluster munition casualties recorded, 12 have recognized responsibility for cluster munition victims (see table below).

States Parties which have reported a responsibility for cluster munition victims

|

Afghanistan |

|

Albania |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) |

|

Chad |

|

Croatia |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

|

Iraq |

|

Lao PDR |

|

Lebanon |

|

Montenegro |

|

Sierra Leone |

|

Somalia |

At least two other States Parties which have had cluster munition casualties reported, Colombia and Mozambique, may also have responsibility to assist cluster munition victims. Both are also States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty and have recognized responsibility for significant numbers of mine survivors and their needs.

In 2019, Colombia reported that “since the date of entry into force of the Convention [on Cluster Munitions] for the Colombian State there are no reports or records on victims of cluster munitions”.[178] The convention entered into force for the country on 1 March 2016, and in November 2017, the Supreme Court of Colombia upheld the decision of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) case, Santo Domingo Massacre v. Colombia, regarding redress for cluster munition victims of an attack in 1998.[179] The IACHR prescribed measures for remedy that are essentially consistent with the victim assistance obligations of the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[180] In May 2009, Colombia’s then-Minister of Defense and later Nobel Peace Prize winning president, Juan Manuel Santos, acknowledged that the Colombian armed forces had used cluster munitions in the past “to destroy clandestine airstrips and camps held by illegal armed groups” and noted that the submunitions sometimes did not explode and “became a danger to the civilian population.”[181] In 2010, the Ministry of National Defense said that the Colombian Air Force last used cluster munitions on 10 October 2006 “to destroy clandestine airstrips belonging to organizations dedicated to drug trafficking in remote areas of the country where the risk to civilians was minimal.”[182]

In 2020, Mozambique reported that “at the moment there is no evidence of victims of cluster munitions.”[183] Previously, Mozambique reported on victim assistance efforts under the Convention on Cluster Munitions and also stated that “Additional surveys are needed to identify victims of cluster munitions.”[184] No such surveys were reported. However, casualties which occurred in Mozambique during the time of cluster munition attacks by Rhodesian forces were likely mostly Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) forces.[185]

Non-signatories Cambodia and Vietnam are also viewed as countries with the most significant numbers of cluster munition victims in need of assistance and support.[186] Both Cambodia and Vietnam have recognized the need to assist cluster munition victims and provided information on their victim assistance efforts at early meetings of States Parties of the Convention on Cluster Munitions. Cambodia and Vietnam reported on their implementation efforts in accordance with the convention’s specific requirements of planning, coordination, and the integration of victim assistance into rights-based frameworks, such as the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).[187]

Victim assistance obligations and relevant international frameworks

States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with victims under their jurisdictionare legally bound to implement adequate victim assistance in accordance with applicable international humanitarian law and human rights law.[188] All but two of the States Parties with cluster munition victims, Lao PDR and Lebanon, are also party to the Mine Ban Treaty, and are responsible for providing assistance to mine survivors. Most of these states have also received focused attention and support in developing victim assistance programs through the mechanisms of the Mine Ban Treaty and its Implementation Support Unit: Afghanistan, Albania, BiH, Chad, Croatia, Guinea-Bissau, Montenegro,[189] Iraq, and Somalia.