Cluster Munition Monitor 2022

The Impact

Jump to a specific section of the chapter:

Assessing the Impact: Contamination | Casualties

Addressing the Impact: Clearance | Risk Education | Victim assistance

This summary reports on the impact of cluster munitions globally. It charts the efforts and challenges to address the impact in States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions with responsibility for clearance of cluster munition remnants and for assistance to victims.

As of the end of 2021, the total number of cluster munition casualties for all time, recorded by the Monitor, reached 23,082 including casualties from both cluster munition attacks and unexploded submunitions. Estimates calculated from various sources range from 56,500 to 86,500 casualties for all time, globally.

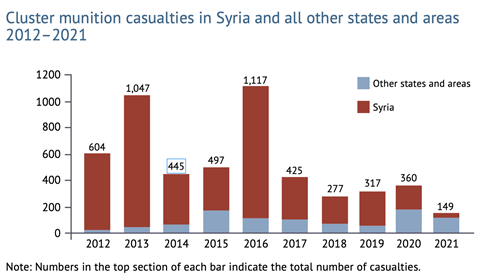

The Monitor recorded a total of 149 cluster munition casualties in 2021 across nine countries and two other areas. This marked a sharp decrease from the 360 casualties recorded in 2020. All casualties reported in 2021 were caused by cluster munition remnants. This was the first year in a decade that saw no new casualties from cluster munition attacks.

This notable decline in casualties was immediately eclipsed by shocking reports of hundreds of casualties from cluster munition attacks in Ukraine, after Russia invaded the country in February 2022. Preliminary data indicates that as of July 2022, at least 689 casualties from cluster munition attacks were reported to have occurred in Ukraine, with many others unrecorded.

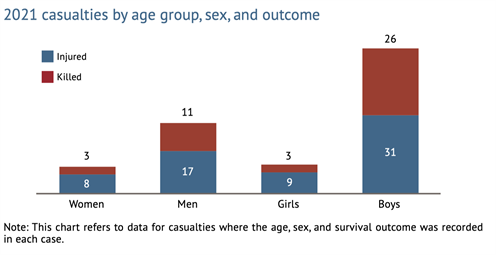

Children accounted for two-thirds of all cluster munition casualties in 2021, where the age was recorded. Men and boys made up 80% of casualties where the sex was recorded. While total annual casualties decreased in 2021, the number of new casualties in States Parties Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon increased, while several non-signatory countries recorded new casualties. As has been the case each year since 2012, Syria had the highest annual casualties of any country. However, the number of casualties recorded in Syria decreased, with 2021 seeing its lowest annual recorded total since 2012.

The period 2021–2022 saw some positive developments as countries began to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, with mine action operations returning to near-normal in many states. The Lausanne Action Plan, which lays out the five-year strategic commitments of States Parties to further their efforts to address the impact of cluster munitions, was finally adopted during the second part of the convention’s Second Review Conference in September 2021.

Yet in many respects the period continued to be challenging. The longer-term socio-economic effects of the pandemic impacted state finances, in some cases changing funding priorities. Global insecurity and the outbreak of hostilities hampered progress towards a cluster munition free world. In Ukraine in 2022, conflict with Russia resulted in new cluster munition contamination.

In 2021, no States Parties completed clearance of cluster munition remnants. Ten States Parties remain contaminated with cluster munitions. Two signatories, 14 non-signatories, and three other areas have, or are believed to have, land containing cluster munition remnants.

States Parties reported clearing more than 61km² of land and at least 81,043 cluster munition remnants in 2021.[1] The clearance figure is slightly below that of 63km² in 2020, although two States Parties—Croatia and Montenegro—finished clearance in 2020, contributing to that overall total. Figures for any clearance that took place in Somalia during 2021 were not reported. No clearance took place in Chile in 2021. Chile conducted technical survey of its contaminated areas during 2021 and was planning to begin clearance in 2023.

Requests to extend Article 4 clearance deadlines have been made every year since the first submissions in 2019. In 2021, extension requests were granted to Afghanistan, Chile, and Mauritania. During 2022, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Chad, and Chile submitted extension requests. Only two States Parties—Iraq and Somalia—remain within their original Article 4 deadlines, but neither appear to be on target to meet them.

In 2021, the ongoing socio-economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to increase risk-taking in contaminated areas as people were forced to rely on harmful coping mechanisms. In Lao PDR and Lebanon, it was reported that economic hardship likely encouraged high-risk behaviors, as people sought to supplement falling incomes.[2] Men remained a particularly high-risk group due to livelihood activities such as cultivation, collection of forest products, hunting, and fishing, all of which can take them into contaminated areas. Children, particularly boys, were susceptible to the lure of cluster munition remnants. Both Lao PDR and Lebanon saw tragic incidents in 2021, where groups of children playing with cluster munition remnants were killed and injured.

Risk education continued to be conducted in non-signatories Libya, Syria, and Yemen, often in the context of ongoing conflict and insecurity. The outbreak of hostilities in Ukraine in early 2022 prompted operators to increase the provision of risk education via digital means, to reach as many affected people as possible. COVID-19 restrictions continued to impact the delivery of risk education in some countries.

Victim assistance efforts, under Article 5, faced increasing challenges. Slow progress in many States Parties was apparent, while such efforts in Afghanistan and Lebanon faced drastic crises in resources. In several States Parties, local and international partners worked to address major gaps in the availability, accessibility, and sustainability of healthcare and rehabilitation services. Limited progress was reported in access to economic inclusion programs and in the provision of financial assistance to victims. As in previous years, psychological support was severely lacking given the high level of need for such services.

Cluster munition remnants contamination

Global contamination

The number of states and other areas affected by cluster munition remnants remains unchanged from 2020. In total, 26 states and three other areas were known or suspected to be contaminated by cluster munition remnants as of 1 August 2022. Ten are States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and have clearance obligations, while two are signatories. Fourteen non-signatories and three other areas are also affected by cluster munitions.

Estimated cluster munition remnants contamination (as of 31 December 2021)

|

Massive (more than 1,000km2) |

Large (100–1,000km2) |

Medium (10–99km2) |

Small (less than 10km2) |

Residual contamination/ unknown |

|

Lao PDR Vietnam |

Cambodia Iraq

|

Azerbaijan Chile Kosovo Mauritania Nagorno-Karabakh Syria Ukraine Yemen

|

Afghanistan BiH DRC Georgia Germany Iran Lebanon Libya Serbia Somalia South Sudan Sudan Tajikistan Western Sahara |

Angola Armenia Chad

|

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold; signatories are underlined; and other areas are in italics.

Cluster munition remnants contamination in States Parties

States Parties that have completed clearance

Under Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties are obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under their jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention.

No States Parties reported completion of clearance of cluster munition remnants in 2021.

A total of 10 States Parties have reported completing clearance of cluster munition remnants as required by the convention.[3] Mauritania, which had reported fulfilment of its clearance obligations in September 2013, reported finding new cluster munition remnants contamination in 2019.[4]

States Parties that have declared fulfilment of clearance obligations

|

2020 |

Croatia, Montenegro |

|

2016 |

Mozambique |

|

2013 |

Norway |

|

2012 |

Republic of the Congo, Grenada |

|

2010 |

Palau, Zambia |

|

2009 |

Albania |

|

2008 |

Guinea-Bissau |

Extent of contamination in States Parties

Action 18 of the Lausanne Action Plan requires States Parties to identify the precise location, scope, and extent of cluster munition remnants contamination in areas under their jurisdiction or control. It also requires contaminated States Parties to establish evidence-based accurate baselines to the fullest extent possible, no later than the Tenth Meeting of States Parties in 2022, or within two years after entry into force of the convention for new States Parties.

As of the end of 2021, five States Parties—BiH, Chile, Germany, Iraq, and Lebanon—had a clear understanding of their contamination based on the conduct of evidence-based surveys. Survey was ongoing in Lao PDR, while Mauritania had conducted an initial assessment of contamination. State Party Chad submitted an extension request in 2022 for the conduct of survey in the northern province of Tibesti. Afghanistan had a clear picture of contamination in accessible areas in 2021, but reported the need to survey previously inaccessible areas. Somalia had yet to conduct a survey of contamination and provided no updates on progress for 2021.

Massive cluster munition remnants contamination (more than 1,000km²) exists in one State Party, Lao PDR, while large contamination (between 100–1,000km²) exists in one State Party, Iraq. Two States Parties—Chile and Mauritania—are believed to have medium contamination (between 10–99km²). Five States Parties—Afghanistan, BiH, Germany, Lebanon, and Somalia—each have less than 10km² of contaminated land. The extent of remaining contamination in Chad is unknown as survey has yet to be conducted.

Lao PDR is the State Party most heavily contaminated by cluster munition remnants. Though the full extent of contamination is not known, 15 of Lao PDR’s 18 provinces are contaminated, with nine heavily contaminated.[5] As of the end of December 2021, the total extent of confirmed hazardous area (CHA) in surveyed areas totaled 1,522.79km², across 10 provinces.[6] Clearance operators have reported the presence of at least 186 types of munitions in Lao PDR.[7]

In Iraq, the Regional Mine Action Center for the south of the country (RMAC South), reported that as of the end of 2021, cluster munition remnants covered a total area of 178.14km² across the north, center, and south of the country.[8] The majority of contaminated areas were found in southern Iraq (157.68km²), though contamination is also found in the Middle Euphrates region (10.11km²) and in the north, including in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (10.35km²).[9] In 2021, 29.32km² of new cluster munition remnants contaminated areas were identified through non-technical survey in the north, center, and south of Iraq. An environmental sanctuary in Basra province was found to have 10km² of contamination following initial surveys.[10]

Contamination in Chile is limited to land that was used for military training, in three ranges belonging to the Chilean Air Force and on one army base.[11] In its revised Article 4 deadline extension request, submitted in June 2020, Chile stated that its estimate of contamination was 64.61km² across the four sites, according to non-technical survey completed in 2019.[12] During 2021, a total of 33.84km² was cancelled after technical survey, leaving 30.77km² of CHA across the four sites.[13]

In 2019, Mauritania discovered previously unknown contaminated areas, dating from 1980 and 1990.[14] After an initial assessment in February 2021, 14.02km² was found to be contaminated with cluster munition remnants. These areas are all located in the region of Tiris Zemmour in the north, bordering Western Sahara.[15] In April 2022, Mauritania reported that cluster munition remnant contamination comprised 10 areas totaling 14.41km², contaminated with BLU-63 and Mk-118 submunitions.[16]

The Taliban-led government in Afghanistan stated that as of April 2022 there was a total of 9.9km2 of contamination remaining in the country. This consisted of 16 areas: 11 surveyed in 2021 and five uncleared in previous years. These areas are located in four provinces, reported as Faryab, Nangarhar, Paktya, and Samangan. A nationwide survey was needed for Afghanistan. This was considered possible due to newly available access to areas that had previously been difficult to reach, due to security concerns and the need for complex negotiations.[17]

The Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) told the Monitor that as of the end of 2021, cluster munition remnants contamination in Lebanon totaled 6.27km² of CHA in three areas: Bekaa, Mount Lebanon, and southern Lebanon.[18] This included 0.12km² of new contamination across 11 sites in the northeast of the country, and 0.11km² of hazardous areas found across three sites elsewhere and as a result of corrections to the perimeters of six existing sites.[19]

Cluster munition remnants contamination in Germany comprised an area not exceeding 11km² in Wittstock—in a former military training area located 80km northwest of Berlin.[20] As of March 2022, Germany reported clearing 4.73km² of areas suspected of contamination since 2017, leaving 6.27km² still to be cleared. Germany has provided slightly different figures as to its extent of contamination remaining.[21]

Cluster munition remnants contamination in BiH primarily results from the 1992–1995 conflict related to the break-up of the former Yugoslavia.[22] BiH reported in 2022 that the remaining area contaminated with cluster munition remnants totaled 0.77km², across 13 suspected hazardous areas (SHAs). Eight of these areas were already in the process of being cleared.[23]

In June 2021, the National High Commission for Demining (Haut Commissariat National de Déminage, HCND) in Chad reported that the last area known to be contaminated—742,657m² in Delbo village, West Ennedi province—had been cleared and was awaiting quality assurance to complete the land release process.[24] Yet Tibesti province in the northwest of the country had not been subject to survey, and in 2017–2018 Mines Advisory Group (MAG) had indicated the possibility that cluster munition remnants could be found there, particularly near former Libyan military bases.[25] In 2022, Chad submitted an Article 4 deadline extension request in order to conduct non-technical survey of 19.05km² of land in Tibesti province to confirm any contamination.[26]

The extent of contamination in Somalia is unknown but believed to be limited to border areas with Kenya, in the north of Jubaland state. No survey of contaminated areas has been possible, primarily due to a lack of funding and inaccessibility amid armed conflict.[27] Somalia had not provided any updates on contamination as of 1 August 2022.

Unconfirmed contamination in States Parties

State Party Colombia may have a small amount of residual contamination, though it states that no known evidence has been found.[28] A World War II-type “cluster adapter” of United States (US) origin was used during an attack at Santo Domingo in 1998.[29] The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) found that the Colombian Air Force had used an AN-M1A2 bomb, which it said meets the definition of a cluster munition.[30]

In the United Kingdom (UK), it is estimated that more than 2,000 crates of AN-M1A1 and/or AN-M4A1 “cluster adapter” type bombs remain in UK waters at Sheerness, off the east coast of England, in the cargo of a sunken World War II ship.[31] In February 2022, it was reported that Royal Navy specialists were undertaking survey and risk assessments of the site before any further work can be conducted to remove the ship and its contents.[32]

Cluster munition remnants contamination in signatories

Two signatories to the Convention on Cluster Munitions—Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—remain listed as having cluster munition remnants contamination. Signatory Uganda completed clearance in 2008.[33]

Angola has no confirmed contamination, but there may remain abandoned cluster munitions or unexploded submunitions. In past years, some cluster munition remnants have been found and destroyed through explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) call-outs.[34]

In August 2020, the DRC reported to the Monitor that several areas contained cluster munition remnants, although these areas had not been surveyed and their size was yet to be determined.[35] In May 2022, the DRC submitted a voluntary Article 7 report, in which it reported that survey had confirmed six CHAs totaling 0.16km². The contamination was reported to comprise cluster munition remnants dating from 1998. Four provinces in the DRC contained contaminated land: Equateur (120,398m²), Ituri (3,406m²), South-Kivu (718.8m²), and Tanganyika (37,000m²).[36] The six CHAs were reported to be marked, but were located in difficult-to-access areas.[37]

Cluster munition remnants contamination in non-signatories and other areas

Fourteen non-signatories and three other areas have, or are believed to have, land containing cluster munition remnants on their territories. The only non-signatory to have completed clearance of cluster munition remnants is Thailand, in 2011.

The full extent of contamination in many of the non-signatories and other areas is not known. However, Vietnam is believed to have massive cluster munition remnants contamination (more than 1,000km²), while Cambodia has large contamination (between 100–1,000km²). Four non-signatories and two other areas are each believed to have between 10–99km² of contamination, while seven non-signatories and one other area are each thought to have less than 10km². The extent of contamination in Armenia is not known.

Vietnam is massively contaminated by cluster munition remnants, but no accurate estimate of the extent exists. In 2022, Vietnam National Mine Action Center (VNMAC) reported to the Monitor that areas contaminated with explosive remnants of war (ERW), of all types, comprised more than 5.6 million hectares (56,000km²). This represents more than 17% of Vietnam’s total land area. The contamination is concentrated mostly in the central provinces of Quang Tri, Quang Binh, Ha Tinh, Nghe An, and Quang Ngai.[38]

Cambodia has raised its overall estimate of cluster munition remnants contamination in recent years after the implementation of survey. The Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA) reported 698km² of total contamination, as of the end of December 2021. This represents an increase on the 658km² reported at the end of 2020.[39] Most contamination is concentrated in the northeastern provinces, along the borders with Lao PDR and Vietnam.[40]

New cluster munition remnant contamination occurred in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and in the area of Nagorno-Karabakh, as a result of use of cluster munitions during the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh in October 2020.[41]

In Armenia, new contamination from the conflict was identified in the Syunik region, bordering Azerbaijan, in 2021. During the conflict, Davit Bek, in Kapan municipality of Syunik province, was also contaminated with explosive ordnance, including cluster munitions.[42]

In Nagorno-Karabakh, the HALO Trust has worked to clear areas under the control of ethnic Armenian authorities, while the Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) has carried out clearance in areas controlled by Azerbaijan. A survey by the HALO Trust estimated that more than 16km2 of land was contaminated, while almost 2,000 unexploded submunitions were cleared from November 2020 to November 2021. The survey found that 68% of inhabited settlements had either cluster munition contamination or evidence of cluster munition use. After the ceasefire in November 2020, more than 20% of land in Stepanakert, the capital of Armenian-controlled areas of Nagorno-Karabakh, was initially contaminated with unexploded items. By May 2022, the HALO Trust had completed clearance of all known contamination in the city. Clearance of Armenian-controlled areas in Nagorno-Karabakh was estimated to require at least another four years, yet funding was lacking and staff capacity required an increase of 40%.[43]

The extent of contamination in both Azerbaijan, and the parts of Nagorno-Karabakh controlled of Azerbaijan, was not reported in 2021.[44] However, casualties from cluster munition remnants continued to be reported in Azerbaijan into 2022, evidencing contamination.[45]

Cluster munitions have been used extensively in Syria, across 13 of its 14 governorates, since 2012. Cluster munition attacks in Syria have decreased since mid-2017,[46] yet the weapons were still in use throughout 2019 and 2020, with the last attack recorded in March 2021. Subsequent attacks may have gone unrecorded.[47] From late April until June 2019, Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported attacks on opposition-controlled areas of Aleppo, Hama, and Idleb governorates on a daily basis.[48] Prior to that, cluster munition use and contamination was reported in the governorates of Aleppo, Dar’a, Deir-ez-Zor, Hama, Homs, Idleb, and Quneitra, as well as in the Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta.[49]

Extensive cluster munition attacks, resulting in contamination, were reported in Ukraineduring 2022 amid the Russian invasion of the country. In 2021, the full extent of contamination from unexploded submunitions was unknown, but was limited to the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in the east and dated from conflict in 2014–2015.[50] Since Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, at least 10 other regions have been affected by cluster munitions: Chernihiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, Kharkiv, Kherson, Luhansk, Mykolaiv, Odesa, Sumy, and Zaporizhzhia.

In 2014, Yemen identified approximately 18km² of suspected cluster munition hazards, though the escalation of armed conflict since March 2015 has increased the extent of contamination in northwestern and central areas of the country.[51] The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) confirmed in 2020 that cluster munition and other ERW contamination is widespread in the north.[52] In southern Yemen, with the exception of a few areas where the frontlines have shifted, there is no cluster munition remnants contamination.[53]

In Kosovo, as of the end of 2021, the Kosovo Mine Action Centre (KMAC) reported 11.37km² of cluster munition remnants contamination, across 44 affected areas.[54]

Non-signatories Georgia, Iran, Libya, Serbia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tajikistan, and the area of Western Sahara are known or believed to each have less than 10km² of cluster munition remnants contamination.

Georgia is thought to be free of contamination, though South Ossetia—a disputed territory not controlled by the government—is a possible exception.

The extent of contamination in Iran is not known but is believed to be small.

Cluster munition remnants contamination in Libya is primarily the result of armed conflict in 2011 and renewed conflict since 2014, particularly in urban areas. In 2019, there were several instances or allegations of cluster munition use by forces affiliated with the Libyan National Army (LNA), including an attack on Zuwarah airport in August 2019 where RBK-500 cluster munition remnants were found, and during attacks in and around Tripoli in May and December 2019.[55] However, contamination was reported to be lower than that from other victim-activated explosive devices such as booby-traps, antipersonnel landmines, and improvised mines.[56]

Three municipalities in Serbia remain contaminated with cluster munition remnants.[57] Serbia reported 0.99km² of contamination—made up of 0.41km² of CHA and 0.58km² of SHA—as of the end of 2021.[58]

South Sudan reported 5.49km² of contamination, with 4.84km² CHA and 0.65km² SHA.[59]

Sudan reported 0.14km2 of cluster munition remnants contamination as of the end of December 2021, with 5,820m² CHA and 136,582m² SHA.[60]

Tajikistan reported 2.07km² of cluster munition remnants contamination, all classified as CHA. This is up from the 0.79km² reported in 2020 due to the discovery of new hazard areas.[61]

Western Sahara was reported to have 2.09km² of contamination as of December 2021.[62]

The Monitor gathers data on cluster munition casualties recorded each year in affected states, and compiles annual casualty totals. The Monitor also records available data on past casualties, to update all-time casualty totals at the national level, and to revise aggregated global historical data on cluster munition casualties.

As of the end of 2021, the Monitor has identified a total of 23,082 cluster munition casualties, across 39 countries and other areas, for all time. However, a better indicator of the number of casualties is derived from various state estimates, which collectively place the total up to, or more than, 56,500 global casualties.

The 149 cluster munition casualties recorded in 2021 marked a sharp fall from the 360 recorded in 2020. Notably, 2021 was the first year in a decade that saw no new recorded casualties due to cluster munition attacks.[63] Casualties from cluster munition attacks had been recorded each year from 2012, when cluster munitions were used in Syria.

Yet this progress in 2021 has been overshadowed by the devastating number of cluster munition attacks causing casualties during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. There have been reports of hundreds of casualties from such attacks, as well as emerging reports of casualties from contamination left by unexploded submunitions due to this new use. While these early reports do not yet represent a full or precise account of the situation, they clearly indicate the extensive and horrendous impact of cluster munitions in Ukraine.

Since the Russian invasion on 24 February 2022, preliminary data compiled by the Monitor indicates that 689 casualties were reported during cluster munition attacks in Ukraine as of July 2022.[64] These reported casualties, which sometimes occurred during indiscriminate shelling involving other weapons alongside cluster munitions, included 215 people killed and 474 injured. All of the casualties in Ukraine were civilians, where their status was reported.

In addition to local and national media reporting, HRW and Amnesty International documented extensive casualties through July 2022.[65] In June 2022, the Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine was reported to be investigating cluster munition attacks that had caused 317 casualties (98 killed and 219 injured). Among those casualties, seven children were killed and 25 wounded.[66] The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) reported in June 2022 that there had been extensive use of cluster munitions in Ukraine, mostly from Multiple Launch Rocket Systems, though it focused specifically on casualties from attacks with Tochka-U short-range ballistic missiles carrying cluster submunitions.[67] Among some 20 such ballistic missile strikes with cluster munitions recorded by OHCHR, 10 of the attacks resulted in a collective total of at least 279 civilian casualties (83 killed and 196 injured).[68]

Cluster munition use in Ukraine mostly affected civilian infrastructure, with attacks damaging homes, hospitals, schools, playgrounds, and in one instance a cemetery where mourners were among the casualties. Cluster munition attacks also threatened internally displaced persons (IDPs) and those seeking humanitarian aid outside improvised shelters.[69]

Data on the types of unexploded ordnance causing casualties in Ukraine was limited, yet local media reported that casualties from cluster munition remnants occurred as a result of the new contamination. At least 10 casualties (seven killed and three injured) of unexploded submunitions were reported: nine occurred in Kryvorizka district of Dnipropetrovsk province, where thousands of submunitions were cleared by the end of April. Another casualty was reported in Mykolaiv.[70]

Global cluster munition casualties

As of the end of 2021, the total number of cluster munition casualties recorded by the Monitor globally for all time reached 23,082. The total includes casualties resulting directly from cluster munition attacks (4,656) and casualties from unexploded remnants (18,426). Data begins in the mid-1960s amid extensive cluster munition attacks by the US in Southeast Asia, and continues to the end of 2021. The three countries with the highest recorded numbers of cluster munition casualties for all time are Lao PDR (7,793), Syria (4,318), and Iraq(3,134).

As many casualties go unrecorded, global casualties may be as high as 56,500; a figure that has been calculated from country estimates. Some estimates put the total number of casualties for all time at 86,500 to 100,000, yet these are based on extrapolations from limited data samples, which may not be representative of national averages or the actual number of casualties.[71]

Casualties directly caused by cluster munition attacks before the convention entered into force have been grossly under-reported. For example, no data or estimate is available for Lao PDR, the most heavily bombed country. Thousands of cluster munition casualties from past conflicts have gone unrecorded, particularly those that occurred during extensive use in Southeast Asia, Afghanistan, and the Middle East (notably in Iraq, where there have been estimates of between 5,500 and 8,000 casualties since 1991).[72] However, since the entry into force of the convention in 2010, reporting on the impact of cluster munition attacks has improved significantly.

Prior to the adoption of the convention in 2008, data on casualties from cluster munition attacks was severely lacking, including those among military personnel and other direct conflict actors, such as non-state armed group (NSAG) combatants and militias. However, even with improved reporting, the disproportionately high ratio of civilians among casualties of cluster munitions—identified during the Oslo Process which created the convention—has remained apparent.

Before 2008, a total of 13,306 cluster munition casualties had been identified globally.[73] Since then, the total number of recorded casualties has increased due to updated surveys identifying more pre-convention casualties; new casualties from historical cluster munition remnants; and due to new cluster munition attacks and further casualties from the remnants they left behind.

Cluster munition casualties have occurred in 15 States Parties to the convention, four signatory states, 17 non-signatories, and three other areas as of the end of 2021.

States and other areas with cluster munition casualties (as of 31 December 2021)[74]

|

More than 1,000 casualties |

100–1,000 casualties |

10–99 casualties |

Less than 10 casualties/Unknown |

|

Iraq Lao PDR Syria Vietnam |

Afghanistan Angola Azerbaijan BiH Cambodia Croatia DRC Eritrea Ethiopia Kosovo Kuwait Lebanon Russia Serbia South Sudan Western Sahara Yemen |

Albania Colombia Georgia Israel Nagorno-Karabakh Sierra Leone Sudan Tajikistan Uganda Ukraine |

Chad Guinea-Bissau Liberia Libya Mauritania Montenegro Mozambique Somalia

|

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold; signatories are underlined; and other areas are in italics.

*Casualties in Ukraine have increased drastically since the end of 2021 as a result of cluster munition attacks after the Russian invasion in February 2022.

The first cluster munition casualties in Mauritania were reported in 2021.[75] Although no casualties were identified in Mauritania before 2021, it is possible that cluster munition incidents occurred in the past that were not disaggregated from casualties caused by landmines and other ERW.

Among the 15 States Parties that had cluster munition casualties recorded up to the end of 2021, 13 have a recognized responsibility for victims under the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[76] Colombia[77] and Mozambique[78] have had cluster munition casualties reported, but have not recognized having any victims and therefore their responsibility to assist victims under the convention. Both are also party to the Mine Ban Treaty and have recognized their responsibility to assist mine survivors.

The majority of recorded cluster munition casualties for all time (57%, or 13,090) occurred in States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

A total of 604 casualties have been recorded in signatories Angola, the DRC, Liberia, and Uganda.[79]

In non-signatory states, 8,971 cluster munition casualties have been recorded for all time.Since 2010, casualties from cluster munition attacks have only occurred in non-signatory states, with these casualties recorded in Azerbaijan, Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen.

In other areas where cluster munition casualties have occurred—Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Western Sahara—a total of 417 casualties were recorded for all time up to the end of 2021.

Cluster munition casualties in 2021

The Monitor recorded a total of 149 cluster munition casualties in 2021 across nine countries and two other areas, including four States Parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and five non-signatories.[80] There was a marked decline in total global casualties in 2021, from 360 in 2020.

All casualties reported in 2021 were caused by cluster munitionremnants. Casualties of cluster munition attacks had been recorded every year from 2012 when cluster munitions were used in Syria, up to 2020. However, 2021 was the first year in a decade that no new annual casualties from cluster munition attacks were recorded.

Cluster munition casualties in Syria and all other states and areas 2012–2021

Cluster munition remnants pose an ongoing threat. Unexploded submunitions disproportionately harm civilians, with children particularly at risk. In 2021, cluster munition remnants caused all 149 casualties attributed to cluster munitions globally, killing 59 people and injuring 90.

Cluster munition remnants casualties in 2021

|

Country/area |

casualties |

|

|

Syria |

37 |

|

|

Iraq |

33 |

|

|

Lao PDR |

30 |

|

|

Yemen |

29 |

|

|

Lebanon |

8 |

|

|

Nagorno-Karabakh |

5 |

|

|

Tajikistan |

2 |

|

|

Mauritania |

2 |

|

|

Azerbaijan |

1 |

|

|

Sudan |

1 |

|

|

Western Sahara |

1 |

|

Note: States Parties are indicated in bold; andother areas in italics.

The actual number of new global cluster munition casualties each year is likely to be far higher than recorded. Inconsistency in reporting, a lack of available data due to insufficient resources, and limited access to conflict-affected areas mean that annual comparisons do not necessarily represent definitive trends. However, casualty data is adjusted over time when new information becomes available and specific patterns of harm are able to be discerned.

In 2021, as in previous years, Syria had the most recorded cluster munition remnants casualties of any country, with 37. This was a significant decrease from the 147 casualties from cluster munition remnants recorded in Syria for 2020 and the lowest annual total recorded since 2012. A further 35 casualties during cluster munition attacks were also reported in the country in 2020. Despite a relative annual decline in casualties recorded for Syria, this continued the trend of Syria having the most annual casualties recorded each year since 2012.[81]

Iraq reported 33 cluster munition remnants casualties in 2021, up from 31 in 2020. This marked the highest annual total recorded in Iraq since 2010.

Lao PDR recorded 30 cluster munition remnants casualties in 2021; a significant increase from eight in 2020, but still fewer than the 51 casualties recorded in 2016.

In Yemen, 29 cluster munition remnants casualties were recorded in 2021, up from 11 in 2020. Data collection challenges meant that casualties were likely significantly under-reported.

In Lebanon, eight casualties were recorded in 2021, all of whom were children. This marked a sharp increase on 2020, when for the first time since 2006 no casualties were recorded.

While the number of cluster munition casualties decreased globally in 2021, casualties in States Parties Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon increased. For these countries, annual casualties recorded in 2021 contrasted sharply with the totals recorded when the convention entered into force in 2010, when eight casualties were recorded in Lao PDR, one in Iraq, and 14 in Lebanon.

In Azerbaijan, one casualty was recorded in 2021. In the area of Nagorno-Karabakh, five unexploded submunition casualties occurred in 2021. In the regions affected by the conflict in both Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh, strenuous efforts to raise awareness among populations at risk and to conduct urgent clearance likely contributed to reducing casualty numbers. However, casualties may have gone unrecorded.

In Tajikistan, two cluster munition remnant casualties resulted from the same incident. Prior to 2021, no casualties from cluster munition remnants had been reported in the country since 2007.

Mauritania recorded two casualties in 2021. Sudan and the area of Western Sahara each recorded one casualty in 2021.[82] None of these states or areas had recorded any cluster munition remnant casualties in 2020.

No disaggregated data was available on cluster munition remnants casualties in Afghanistan in 2021, which recorded three casualties in 2020. Cambodia recorded no casualties from cluster munition remnants in 2021, compared to one in 2020 which was its first casualty since 2017.

Cluster munition casualty demographics

Civilians accounted for 97% (144) of all casualties recorded during 2021. Three casualties were deminers, while another two casualties did not have their civilian or military status recorded.

A very high ratio of civilian casualties corresponds with findings based on analysis of historical data on cluster munition casualties. This consistent and foreseeable disproportionate impact on civilians is due to the indiscriminate nature of these weapons.

2021 casualties by age group, sex, and outcome

In 2021, the proportion of child casualties of cluster munitions increased alarmingly, rising to two-thirds (66%) of total recorded casualties, where the age was known.[83] Previously, children accounted for 44% of casualties from cluster munition remnants in 2020.

In Lao PDR in 2021, more than half (16) of the 30 recorded cluster munition remnant casualties were children (11 boys and five girls).[84]

In Lebanon, the eight child casualties of cluster munition remnants in 2021 were all boys. Seven were from Syria and were playing when the explosions occurred, while one was from Lebanon.

In Iraq, 19 (65%) of the 33 cluster munition casualties recorded in 2021 were children (17 boys and two girls).

The average age of child casualties in 2021 was 10 years old. Twenty-two of the child casualties were under 10, while the youngest was just two years old. Of the child casualties where the sex was known, 82% were boys and 18% were girls.[85]

Where the sex was known, 20% of casualties in 2021 were recorded as ‘female’ (or 23 of 114).[86] Among those casualties, 52% were girls and 48% were women. Among the remaining 80% of casualties recorded as ‘male,’ 67% were boys and 33% were men.

In 2021, there was a marked difference in survival outcome in relation to the sex of casualties: 47% of male casualties were killed, compared to 26% of female casualties. This represented a reversal of the overall trend in 2020, when half of female casualties were killed.

Coordination, strategies, and planning

Clearance

Strong coordination is an important aspect of national ownership of mine action programs, enabling efficient and effective operations.

In 2021, clearance programs in seven States Parties with cluster munition contamination—BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia—were coordinated through national mine action centers. In States Parties Chile and Germany, where contamination is found only on former military bases, the defense ministries are responsible for coordinating clearance.

In Afghanistan, the international community has largely suspended its support to government institutions since the Taliban took power in August 2021. This has affected the functioning of the national Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC). In September 2021, the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) established a United Nations Emergency Mine Action Coordination Center for Afghanistan (UN-EMACCA), to serve as an independent temporary coordination body for mine action.[87] In October 2021, UNMAS reported that “all funds for the UN-EMACCA will be channeled through and controlled and managed by UNMAS and no funds will be used to support the Taliban or the de facto Government.”[88]

Action 19 of the Lausanne Action Plan requires States Parties to develop evidence-based, costed, and time-bound national strategies and workplans, as part of their Article 4 commitments. As of the end of 2021, seven States Parties—Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mauritania—had strategic plans in place. Germany had a workplan for its extension period to 2025, while Chile prepared a workplan for clearance as part of its Article 4 extension request. Somalia’s mine action strategy expired in 2020. States Parties Afghanistan, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Mauritania updated or were in the process of updating their national mine action strategies in 2021.

With technical and financial support from the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), Afghanistan was developing a new five-year strategic plan during 2021.[89] It was reported that the Mine Action Programme of Afghanistan (MAPA) would likely revise the plan towards a solely humanitarian focus, considering the governance changes in 2021.[90]

In Iraq, the Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) and the Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA) prepared the first integrated strategic plan for the mine action sector, the National Mine Action Strategic Plan 2022–2028, with support from GICHD and UNMAS.[91] The plan was due to be completed in May 2022.[92] Yet its focus was primarily to reflect the new priorities arising from landmine contamination that occurred during the conflict with Islamic State.[93]

In Lao PDR, the national strategy, Safe Path Forward, was updated for the period 2021–2030, and was expected to be approved by mid-2022.[94] The National Regulatory Authority for the UXO/Mine Action Sector (NRA) in Lao PDR has also developed a new five-year plan for the sector covering 2021–2025, to replace the expired 2016–2020 workplan.[95]

Mauritania had in place a National Mine Action Strategic Plan for 2021–2027, which replaced its previous plan for 2016–2020.[96] The plan aims to strengthen the capacity of the National Humanitarian Demining Programme for Development (Programme National de Déminage Humanitaire pour le Développement, PNDHD) through the retraining of operational staff and deminers. It also planned for the conduct of non-technical and technical survey, and for the clearance of 27 areas.[97]

The three States Parties submitting Article 4 deadline extension requests in 2022 are required, in line with Action 20 of the Lausanne Action Plan, to provide annual workplans which include projections of the amount of cluster munition contaminated land to be addressed annually.

BiH’s National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025 was adopted in January 2019, and addresses contamination from both mines and cluster munition remnants. However, BiH did not include a detailed workplan for clearance when it submitted its Article 4 deadline extension request in May 2022.[98]

Chad did not include a detailed workplan as part of its Article 4 deadline extension request to conduct non-technical survey in Tibesti province.[99]

In 2022, as part of its Article 4 extension request and after feedback from the Article 4 Analysis Group, Chile included a detailed workplan for clearance of cluster munition remnants based on the findings of technical survey conducted during 2021.[100] Clearance operations are planned to begin in 2023 and to be completed in 2026.[101]

Risk education

In 2021, nine cluster munition contaminated States Parties had institutions in place which served as risk education focal points: Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Chile, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Somalia.

In most cases, the risk education program is coordinated by the respective national mine action center. For school-based programs in Chile, Iraq, and Lao PDR, the education ministry in each country takes on a coordination role.[102]

Action 27 of the Lausanne Action Plan requires that States Parties develop national strategies and workplans for risk education, drawing on best practice and standards.

Risk education is included within the national mine action strategies of Afghanistan, BiH, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mauritania. The newly updated mine action strategies of Afghanistan, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Mauritania all included sections and objectives on risk education.[103]

As a core part of operational planning, States Parties should include detailed, costed, and multiyear plans for risk education within Article 4 deadline extension requests. There remains much room for improvement in this regard. In 2021, only Afghanistan included information on risk education activities and a budget for risk education, within its extension request.[104] Mauritania provided limited information on risk education, in response to questions from the Article 4 Analysis Group.[105] In 2022, neither BiH or Chad included risk education workplans or budgets in their initial extension requests. Chile did not include risk education in its extension request due to the contamination being in military zones where public access is not permitted.

Victim assistance

States Parties with responsibility for cluster munition victims are obliged under the Convention on Cluster Munitions to develop a national plan and budget for victim assistance. Action 33 of the Lausanne Action Plan commits states to designate a national focal point, and to address the needs and rights of victims according to a measurable national plan. Among States Parties with victims, all have a designated victim assistance focal point, except Croatia and Sierra Leone. No specific victim assistance coordination was reported in Afghanistan, following the Taliban takeover in 2021.

In Lao PDR, the Victim Assistance Technical Working Group continued to be responsible for coordination. In Lebanon, 10 meetings were held in 2021, which focused on organizing a national victim survey and classifying the data collected. Somalia did not report on coordination efforts following the drafting of its victim assistance strategy. Albania and Iraq reported ad hoc coordination processes, addressing specific needs as they arose.

In BiH, no in-person meetings were held in 2020–2021 due to COVID-19 restrictions, with all coordination taking place virtually. In 2021, Guinea-Bissau was developing a victim assistance coordination mechanism. Croatia’s coordination body for victim assistance remained inactive, while Montenegro and Sierra Leone had no specific coordination mechanisms in place.

As of the end of 2021, seven of the States Parties with cluster munition victims had strategies or plans in place for victim assistance and disability rights: Albania, BiH, Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon. Chad’s National Plan of Action on Victim Assistance is reported not to have been implemented since its inception in 2018, although other project-related victim assistance planning has been carried out.

In 2021, Guinea-Bissau adopted a five-year National Strategy for the Inclusion of People with Disabilities, which was discussed in early 2022 in relation to victim assistance measures.

In Lao PDR, a Victim Assistance Framework for 2021–2025 was being developed in 2021.[106] A review of the implementation of its UXO/Mine Victim Assistance Strategy 2014–2020 was being undertaken to inform the development of the new framework, with Lao PDR’s national plan and budget to be updated once the framework is completed. This process was consultative, and included input from unexploded ordnance (UXO) survivors and stakeholders including the Lao Disabled People’s Association (LDPA), the Lao Disabled Women’s Development Centre (LDWDC), the Centre for Medical Rehabilitation, and the Cooperative Orthotic and Prosthetic Enterprise (COPE).[107]

Afghanistan and Somalia had each developed new national disability strategies in 2019, which were pending formal approval and adoption as of the end of 2021. It was not known if the plan for Afghanistan was still under consideration after the Taliban takeover in August 2021.

Four States Parties which have reported responsibility for cluster munition victims did not have an active strategy or draft plan in 2021. Croatia has not yet replaced its Action Plan to Help Victims of Mines and UXO, which expired in 2014. Mauritania did not have a specific victim assistance strategy; however, victim assistance is included in its five-year mine action strategy. Montenegro and Sierra Leone did not have victim assistance plans, yet both had a comparatively small number of recorded victims and have broader disability legislation.

Summary of mine action management and coordination

|

Mine action coordination mechanism |

Clearance strategy/plan |

Risk education coordination |

Risk education strategy |

Victim assistance coordination |

Victim assistance strategy/plan |

|

Afghanistan |

|||||

|

Directorate of Mine Action Coordination (DMAC) |

National Mine Action Strategic Plan 2021–2026

|

DMAC through RE-TWG |

Included in mine action strategy |

Unknown |

Disability strategy pending approval or not adopted |

|

Albania |

|||||

|

Ministry of Defense/ General Staff of the Armed Forces |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Ministry of Health and Social Protection |

National Action Plan for Persons with Disabilities (NAPPD) 2021–2025 |

|

BiH |

|||||

|

BiH Mine Action Center (BHMAC) |

National Mine Action Strategy 2018–2025 |

BHMAC |

Included in mine action strategy |

BHMAC Victim Assistance Working Group |

Included in mine action strategy |

|

Chad |

|||||

|

National High Commission for Demining (HCND) |

National Mine Action Plan 2020–2024 |

HCND |

None |

HCND |

Victim assistance plan adopted in 2018 (not implemented) |

|

Chile |

|||||

|

Ministry of National Defense |

Workplan included in 2022 Article 4 extension request |

Ministry of National Defense in coordination with Ministry of Education |

N/A |

N/A |

None |

|

Croatia |

|||||

|

Ministry of the Interior/Civil Protection Directorate |

National Mine Action Strategy 2020–2026 |

Ministry of the Interior via the Civil Protection Directorate and Police Directorate |

N/R |

Combined, cross-ministry and institutional (including Ministry of Croatian Veterans, Ministry of Health, and the Office of the Ombudswoman for Persons with Disabilities) |

None |

|

Germany |

|||||

|

Federal Ministry of Defence |

Clearance workplan included within its 2019 Article 4 extension request (updated annually) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Guinea-Bissau |

|||||

|

National Mine Action Coordination Centre (CAAMI) |

N/A |

CAAMI |

N/A |

CAAMI |

Five-year National Strategy for the Inclusion of People with Disabilities (adopted in 2021) |

|

Iraq |

|||||

|

Directorate of Mine Action (DMA) and Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency (IKMAA) |

National Mine Action Strategy 2022–2028 |

DMA and Ministry of Education |

Included in mine action strategy |

DMA Victim Assistance department |

Victim assistance plan (adopted by DMA in 2018) |

|

Lao PDR |

|||||

|

National Regulatory Authority (NRA) |

Safe Path Forward III 2021–2030

|

NRA via RE-TWG and Ministry of Education and Sports |

Included in mine action strategy |

NRA Victim Assistance Technical Working Group |

Victim Assistance Framework 2021–2025 (draft) |

|

Lebanon |

|||||

|

Lebanon Mine Action Center (LMAC) |

Humanitarian Mine Action Strategy 2020–2025 |

LMAC via Risk Education Steering Committee |

Included in mine action strategy |

LMAC |

Humanitarian Mine Action Strategy 2020–2025 |

|

Mauritania |

|||||

|

National Humanitarian Demining Programme for Development (PNDHD) |

National Mine Action Strategic Plan 2021–2027 |

PNDHD |

Included in mine action strategy |

PNDHD |

None |

|

Montenegro |

|||||

|

Ministry of Internal Affairs, Directorate for Emergency Situations |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare

|

None |

|

Sierra Leone |

|||||

|

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

None |

None |

|

Somalia |

|||||

|

Somali Explosives Management Authority (SEMA) |

National Mine Action Strategic Plan 2018–2020 (expired) |

SEMA |

None |

SEMA |

Disability and victim assistance strategy pending approval |

Note: N/A=not applicable; N/R=not reported; RE-TWG=Risk Education Technical Working Group.

Standards

Survey and clearance

States Parties Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia all had national standards in place consistent with the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS). However, the standards in place in Chad and Somalia do not cover cluster munition remnants clearance and survey. Chile uses IMAS along with a Joint Demining Manual for its armed forces, while clearance and survey in Germany are conducted according to federal legislation.

In Lao PDR, there are separate standards for UXO clearance and mine clearance operations.[108]

In 2020–2021, national mine action standards in Iraq were reviewed and updated with support from UNMAS.[109] Lebanon conducted a full review of its standards during 2020.[110] Mauritania planned to conduct a review of its standards during its Article 4 extension period from 2022–2024. In 2022, it reported that its standards were being revised.[111]

Some States Parties, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, developed specific COVID-19 prevention and control guidelines for mine action operations in 2020.[112] Iraq approved and circulated the guidelines to relevant stakeholders in 2021.[113]

Risk education

Afghanistan, BiH, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mauritania all have national standards in place for risk education. BiH also has an accreditation guide for risk education operators.[114]

In 2022, Iraq reported that its risk education standard had been updated in line with the revised IMAS 12.10 on Explosive Ordnance Risk Education (EORE). The Arabic version of Iraq’s risk education standard was being translated into English by international operators.[115]

In 2021–2022, Lebanon and Mauritania were in the process of updating their national standards on risk education in line with the revised IMAS 12.10.[116]

Lao PDR planned to update its national risk education standard, which was last revised in 2012; though this was not completed in 2021.[117] In Chad, progress on updating its national standard on risk education was also delayed, reportedly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.[118]

Victim assistance

Under Action 32 of the Lausanne Action Plan, States Parties have committed to consider IMAS when integrating victim assistance into broader mechanisms, strategies, and plans.

IMAS 13.10 on Victim Assistance was fully adopted in October 2021.[119] According to this new standard, national mine action authorities and centers can, and should, play a role in monitoring and facilitating multisector efforts to address survivors’ needs. National authorities should also assist with including survivors and indirect victims of cluster munitions, and their views, in the development of relevant national legislation and policies. The standard notes that national mine action authorities are well placed to gather data on victims and their needs, provide information on services, and refer victims for support.

In 2021, Humanity & Inclusion (HI) worked with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Mine Action Center (ARMAC) to promote best practices in victim assistance in ASEAN countries. This support from HI focuses on updating national victim assistance standards and contributing to international and national policy campaigns, as well as support for livelihood activities.[120]

Lao PDR and Lebanon were both working to update their respective national victim assistance standards in 2021, to bring them in line with IMAS 13.10.[121]

In 2021, government agencies that provide victim assistance services in Iraq, alongside HI and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), held a workshop to form draft national standards on victim assistance in line with IMAS 13.10, with completion targeted for 2022.[122]

Reporting

Under Article 7 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions, States Parties with cluster munition contamination must report annually on the size and location of all cluster munition contaminated areas under their jurisdiction and control, and on the status and progress of clearance and the destruction of cluster munition remnants. States Parties must submit annual transparency reports by 30 April each year.

As of 1 August 2022, only seven out of 10 States Parties with clearance obligations had submitted updated reports for calendar year 2021: BiH, Chile, Germany, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Mauritania.

States Parties also have an obligation to report on risk education.[123] Action 29 of the Lausanne Action Plan commits states to provide data on beneficiaries disaggregated by gender, age, and disability in their transparency reports. Only Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon provided adequate reporting on risk education in their reports for 2021. BiH and Mauritania did not detail activities, or provide disaggregated beneficiary data. Chile and Germany stated that risk education was not needed, as their cluster munition remnants contamination was confined to military training areas.

States Parties must report progress on victim assistance under Article 5. Albania, BiH, Croatia, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Montenegro included information on victim assistance in their reports for 2021.

As of 1 August 2022, five States Parties with clearance obligations and/or a responsibility for cluster munition victims had not submitted their updated annual reports covering activities in 2021. Afghanistan, Chad, and Guinea-Bissau last submitted a transparency report in 2021, for activities in 2020. Somalia failed to submit an annual report in both 2020 and 2021 and Sierra Leone has not provided one since 2011.

Cluster munition remnants clearance

Obligations regarding clearance

Under the Convention on Cluster Munitions, each State Party is obliged to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants in areas under its jurisdiction or control as soon as possible, but not later than 10 years after becoming party to the convention. If unable to complete clearance on time, the State Party may request deadline extensions for periods of up to five years.

Clearance in 2021

In 2021, States Parties reported clearing some 61km² of cluster munition contaminated land, destroying more than 81,000 cluster munition remnants. The clearance figure is slightly lower than the 63km² cleared in 2020. Yet two States Parties, Croatia and Montenegro, finished clearance in 2020, contributing to the higher total.

Monitor data on cluster munition clearance in States Parties is based on information from a range of sources including reporting by national mine action programs, Article 7 transparency reports, and Article 4 extension requests. In cases where varying annual figures are reported by States Parties, details are provided in footnotes, and more information can be found in country profiles on the Monitor website.

Cluster munition remnants clearance in 2020–2021[124]

|

State Party |

2020 |

2021 |

||

|

Clearance (km²) |

CMR destroyed |

Clearance (km²) |

CMR destroyed |

|

|

Afghanistan |

0 |

276 |

0.42 |

32 |

|

BiH |

0.34 |

162 |

0.62 |

2,995 |

|

Chad* |

0.41 |

9 |

0 |

2 |

|

Chile |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Croatia** |

0.03 |

11 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Germany |

1.09 |

971 |

0.85 |

466 |

|

Iraq |

5.67 |

6,146 |

10.16 |

8,202 |

|

Lao PDR |

54.32 |

71,235 |

47.84 |

66,921 |

|

Lebanon |

1.28 |

2,098 |

1.00 |

2,418 |

|

Mauritania |

0 |

0 |

0.18 |

7 |

|

Montenegro** |

0.25 |

15 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Somalia |

0 |

2 |

N/R |

N/R |

|

TOTAL |

63.39 |

80,925 |

61.07 |

81,043 |

Note: CMR=cluster munition remnants; N/A=not applicable; N/R=not reported.

*Chad reported 0.41km2 cleared for the period September 2020–April 2021, but did not specify how much of this clearance took place in 2021.

**Croatia and Montenegro completed clearance of all cluster munition remnants contaminated areas in 2020.

Afghanistan reported that 0.42km² of cluster munition contaminated land was cleared in 2021, resulting in the destruction of 32 submunitions. Clearance was reported to have taken place “in April 2022,” but may have taken place in 2021 through to late March 2022, during the reporting period of Afghan calendar year 1401. No reduction via technical survey was carried out during land release and all sub-surface explosive items were addressed in the hazardous areas.[125]

BiH reported land release of 0.62km² and the destruction of 2,995 cluster munition remnants during 2021.[126] Since 2017, a total of 2.22 km² has been reported as cleared in BiH.[127]

Chad reported releasing 0.74km² of cluster munition contaminated land in the Delbo area of West Ennedi province between September 2020 and April 2021 (0.41km² cleared and 0.33km² reduced), with a total of 11 submunitions cleared and destroyed. It was not reported how much of this clearance took place in 2021.[128] In June 2021, HCND reported that the area was awaiting quality assurance to complete the land release process; this was completed in October 2021.[129]

Chile conducted no clearance in 2021, but carried out technical survey, leading to the reduction of 33.84km² of SHA and the identification of 30.77km² of remaining CHA, across four areas.[130] Chile was planning to undertake clearance of these areas from mid-2023 until June 2026.[131]

Germany cleared 0.85km² of contaminated land during 2021, destroying 466 cluster munition remnants. Between 2017 and 2021, a total of 4.38km² has been cleared within areas of suspected cluster munition remnant contamination.[132]

Iraq reported clearing 10.16km² of cluster munition contaminated land in 2021. An additional 6.48km² was released via technical and non-technical survey.[133] A total of 8,202 submunitions were cleared; 6,906 through battle area clearance and 1,296 through technical survey.[134] Most clearance took place in the south (9.71km²), though 0.45km² was cleared in the Middle Euphrates region.[135]

As in previous years, Lao PDR cleared the most land, 47.84km², in 2021; representing 78% of all reported clearance. This included 45.14km² of agricultural land and 2.7km² of land needed for development.[136] In total, 66,921 cluster munition remnants were destroyed in Lao PDR in 2021; a decrease from the 71,235 destroyed in 2020.[137] More than 98% (47.16km²) of the total clearance for 2021 occurred in the nine most heavily contaminated provinces.[138] Commercial operators accounted for less than 3% of the land cleared in Lao PDR, clearing a total of 1.37km² (1.36km² for development and 0.01km² for agriculture) and destroying 540 cluster munition remnants. About one-third of land cleared by commercial operators was contaminated with cluster munitions (0.51km²).[139] The amount of land cleared with no cluster munition remnants found and destroyed represented just under 2% of the total amount of land cleared in Lao PDR in 2021 (0.86km²).

Lebanon reported releasing 1.24km² of cluster munition contaminated land during 2021. Of the total, 1km² was cleared, 0.1km² was cancelled through non-technical survey, and 0.14km² was reduced through technical survey.[140] The 1km² cleared was down from 1.28km² cleared during 2020. A total of 2,418 cluster munition remnants were cleared and destroyed in 2021 through surface, sub-surface, and rapid response. From 2017–2021, Lebanon cleared a total of 6.1km² of land contaminated by cluster munition remnants.

Mauritaniaundertook an initial assessment of contamination in February 2021, and submitted a request in June 2021 to extend its Article 4 clearance deadline by two years, until 1 August 2024.[141] In 2021, Mauritania cleared 0.18km² of contaminated land, destroying seven cluster munition remnants.[142]

As in 2020, Somalia provided no information on clearance of contaminated areas in 2021.

Article 4 deadlines and extension requests

If a State Party believes that it will be unable to clear and destroy all cluster munition remnants on its territory within 10 years of the entry into force of the convention for that country, it can request an extension to its clearance deadline under Article 4 for a period of up to five years.

Despite progress in addressing cluster munition contaminated areas, the first clearance deadline extension requests were submitted in 2019 by Germany and Lao PDR, both of which received five-year extensions. More requests have been submitted each year since then.

In 2020–2021, Afghanistan, BiH, Chile, Lebanon, and Mauritania submitted extension requests and were each granted extensions to their clearance deadlines. In 2022, Chile submitted a third extension request based on the completion of technical survey. Requests were also submitted in 2022 by BiH and Chad.

Status of Article 4 progress to completion

|

State Party |

Original deadline |

Extension period (no. of request) |

Current deadline |

Status |

|

Afghanistan |

1 March 2022 |

4 years (1st) |

1 March 2026 |

Unclear |

|

BiH |

1 March 2021 |

18 months (1st)

|

1 September 2022 |

Requested 1- year extension until 1 September 2023 |

|

Chad |

1 September 2023 |

N/A |

1 September 2023 |

Requested 13-month extension until 1 October 2024 |

|

Chile |

1 June 2021 |

1 year (1st) 1 year (2nd) |

1 June 2023 |

Requested 3-year extension until 1 June 2026 |

|

Germany |

1 August 2020 |

5 years (1st) |

1 August 2025 |

Expects to complete in 2025 |

|

Iraq |

1 November 2023 |

N/A |

1 November 2023 |

Behind target |

|

Lao PDR |

1 August 2020 |

5 years (1st) |

1 August 2025 |

Behind target |

|

Lebanon |

1 May 2021 |

5 years (1st) |

1 May 2026 |

Unclear |

|

Mauritania |

1 August 2022 |

2 years (1st) |

1 August 2024 |

Unclear |

|

Somalia |

1 March 2026 |

N/A |

1 March 2026 |

Unknown |

Note: N/A=not applicable.

The Lausanne Action Plan notes that sustained efforts are required to ensure that States Parties complete their clearance obligations as soon as possible, and within their original Article 4 deadlines.[143] Only Iraq and Somalia remain within their original deadline, and the number of States Parties on track to meet their Article 4 obligations is decreasing.

Afghanistan hadinitially reported that it would meet its clearance deadline of 1 March 2022 as there was commitment from UNMAS and the US to support clearance of 10 areas.[144] However, the discovery of additional contamination and a change in donor commitments led Afghanistan to submit a four-year extension request until March 2026.[145] The request was granted in 2021. In May 2022, Afghanistan stated that it “commits itself to fulfilling its obligations in relation to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.” The Taliban-led government did not specifically state whether the country was on track to meet its Article 4 clearance deadline.[146

In its 2019 extension request, Germany reported that it should be able to complete clearance of the Wittstock military training area by 2024. Germany has since stated it was confident that the country would be cluster munition free by 2025.[147] In June 2022, Germany reported that 43% (4.73km²) of the 11km² of contaminated land was cleared between 2017 and 25 March 2022,[148] leaving 6.27km² to clear by 1 August 2025.[149] Challenges to the speed of clearance have included high density metal areas, essential fire maintenance work, limited demining personnel, and poor weather conditions.

Iraqreported in February 2022 that it will not meet its clearance deadline of 2023 and plans to submit an extension request.[150] RMAC South reported that challenges to clearance include the fact that national efforts are focused primarily on areas liberated from Islamic State, while new contaminated areas continue to be found through survey, particularly in the south.[151]

Lao PDR indicated that completion of survey would be the priority during its extension period, with an expectation that additional time and international support would be needed.[152] Survey was ongoing in 2021 and will form a basis for long-term planning and clearance prioritization.

In 2021, Lebanon was granted five additional years until 1 May 2026 to complete clearance. LMAC provided a detailed plan based on available assets; and despite the challenge of difficult terrain, believed that it would meet its 2026 deadline.[153] However, Lebanon reported that a decrease in dedicated international funding for cluster munition clearance affected the number of clearance teams. LMAC had also not received any government funding for clearance.[154] LMAC planned to focus on technical survey to speed up task completion, while also restricting destruction of cluster munition remnants to once per week, as opposed to every day, to enable more time for survey and clearance.[155] Operators have said that the 2026 target for completion of clearance is likely to be missed.[156]

In 2021, Mauritania was granted a two-year extension, to 1 August 2024, to complete survey and clearance.[157] During 2022, Mauritania reported that it still needed to confirm the extent of contaminated areas to confirm whether it would be able to meet this deadline.[158]

It is unknown whether Somalia will meet its clearance deadline of 1 March 2026, as it does not have an accurate picture of contamination and has no plan in place for clearance.

Three States Parties submitted extension requests during 2022.

Despite expectations that BiH would complete clearance by its deadline of 1 September 2022, it submitted a second extension request in 2022, asking for a further year.[159] According to the extension request, submitted in May 2022, this was to allow for finalization of documentation, and for additional time if any delays occurred.[160]

Chad reported in June 2021 that it was in the process of clearing its last known contaminated area and that clearance would be completed by the end of July 2021, ahead of its September 2023 deadline.[161] Yet Tibesti province, in the north, is suspected to have some cluster munition remnant contamination around former Libyan military bases. No survey has been conducted there due to insecurity and inaccessibility.[162] In 2022, Chad submitted its first extension request, seeking one year to conduct non-technical survey on 19.05km² of land in Tibesti province.

Chile has made no progress on clearance, despite having been a State Party to the convention since December 2010. In January 2020, Chile asked for an extension period of five years until 2026.[163] In June 2020, the request was revised to a one-year interim extension, to enable technical survey before submitting a second extension request with a clearance plan.[164] In June 2021, Chile submitted a second one-year extension request, without survey having taken place, citing a lack of resources and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.[165] Technical survey was undertaken later in 2021, before Chile submitted its third extension request in April 2022, for a period of three years, to clear 31km² of CHA identified in the survey. Following a preparatory phase, Chile plans to begin clearance operations in 2023 and complete clearance in 2026.[166]

The Article 4 extension requests from BiH, Chad, and Chile will be considered at the Tenth Meeting of States Parties of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in August–September 2022.

Obligations regarding risk education

Article 4 of the Convention on Cluster Munitions states that each State Party shall “conduct risk reduction education to ensure awareness among civilians living in or around cluster munition contaminated areas of the risks posed by such remnants.” Risk education involves interventions aimed at protecting civilian populations and individuals, at the time of cluster munition use, when they fail to function as intended, and when they have been abandoned.

Risk education for cluster munition contamination

States Parties BiH, Iraq, Lao PDR, and Lebanon all reported conducting risk education in 2021. While Afghanistan did not report on risk education, international operators reported that they conducted risk education activities in Afghanistan in 2021 which included messaging on cluster munition remnants.[167] Risk education was also conducted in Chad and Mauritania, although it was not reported whether it specifically targeted the threat of cluster munition remnants.

In Lao PDR, risk education is specifically directed to address the risk behaviors associated with cluster munition remnants.

In other States Parties where cluster munition contamination is mixed with other forms of mine and ERW contamination, which might be more predominant, operators do not conduct specific risk education sessions related to cluster munition remnants.

In Somalia, cluster munition remnants are not included on risk education materials due to there being little evidence of contamination.[168]

Risk education targeting

The Lausanne Action Plan directs States Parties to implement context-specific, tailor-made risk education activities and interventions, which prioritize at-risk populations and are sensitive to gender, age, and disability, as well as the diversity of populations in affected communities.

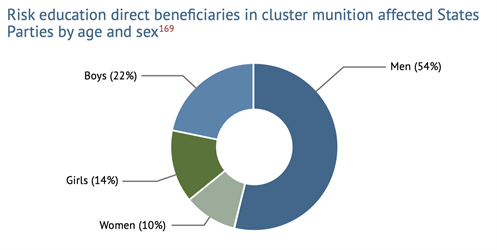

Risk education direct beneficiaries in cluster munition affected States Parties by age and sex[169]

In the majority of States Parties with cluster munition remnants contamination, the ordnance is found in rural areas and directly impacts people who rely on the land and natural resources for their livelihoods. Men are a particularly high-risk group due to their participation in activities which can take them into contaminated areas, such as cultivation, collection of forest products, and hunting and fishing.

According to risk education beneficiary data provided by States Parties Afghanistan, Chad, Iraq, Lao PDR, Lebanon, and Somalia, men formed the largest number of direct beneficiaries of risk education in 2021. At least 472,403 men were reached, representing 54% of all beneficiaries. The largest number of men (409,883) were reached through risk education conducted in Afghanistan.

In BiH, accidents are common in spring and autumn during agricultural work, and when people go to the forest to collect firewood and other raw materials. The Bosnia and Herzegovina Mine Action Center (BHMAC) reported that people often knowingly enter contaminated areas for economic reasons. Target groups for risk education in BiH include farmers, mountaineers, hunters, and people collecting wood and other resources.[170]

In Iraq, since 2020, the DMA has implemented an intensive risk education campaign aimed at Bedouin people in the southern governorate of Al-Muthanna, to address a rise in incidents in spring when Bedouins gather to graze livestock and plant crops.[171] Tourism seasons in Missan and Wassit governorates, and the grazing, transportation, and hunting seasons in Al-Muthanna and Samawah Badia were also a focus of risk education campaigns.[172] This focus continued in 2021, combined with the dissemination of messages via mobile phones and social media.[173]

In Afghanistan, communities living in proximity to hazards were targeted: returnees and IDPs, nomads, scrap metal collectors, and travelers.[174] In Chad, nomads, animal herders, traditional guides, and trackers remained high-risk groups due to their transit through desert areas which may be contaminated.[175] In Mauritania, shepherds, nomads, artisanal miners, and fisherfolk were all considered important groups for risk education.[176]

In Lao PDR, agricultural activities and the collection of natural resources were highlighted as high-risk activities in risk education materials. Casualties in Lao PDR in 2021 were most often caused by people digging the land, cutting grass, or making fires for warmth or cooking.[177]