Landmine Monitor 2007

Mine Action

In most affected countries landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) no longer cause a humanitarian crisis - thanks to the sustained mine action efforts of many organizations, countries and individuals, especially tens of thousands of deminers, over the last decade. Since the origin of modern demining at the end of the 1980s, it is estimated that globally over 1,000 square kilometers of mined land have been cleared and ten times as much released through area reduction and cancellation techniques.

Mine Action in 2006[1]

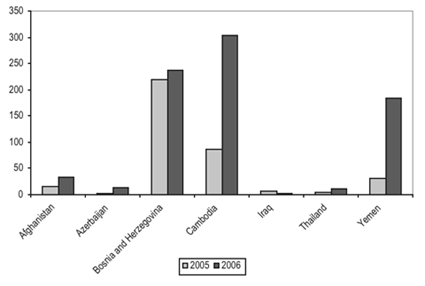

Based on available information, Landmine Monitor believes that mine action programs around the world cleared over 140 square kilometers of mined areas in 2006, as well as over 310 square kilometers of battle areas, although data is not complete and there are significant problems in reporting data (see section below on data gathering).[2] Afghanistan and Cambodia accounted for more than 55 percent of mined area clearance. Afghanistan and Iraq claimed battle area clearance representing two thirds of the global total estimated from reports of mine action programs. Overall, demining operations resulted in the destruction of at least 217,000 antipersonnel mines and almost 18,000 antivehicle mines as well as more than 2.15 million ERW; this total included some 95,000 unexploded submunitions destroyed in Lebanon following the conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in mid-2006.

The figures for mine clearance for calendar year 2006 are very similar to those achieved in 2005 but the total of battle area clearance represents an increase of more than 60 percent on the 190 square kilometers achieved the previous year. In addition, release of suspected hazardous land through survey or other forms of verification (excluding clearance) amounted to a further 860 square kilometers in 2006, triple the figure for 2005,[3] although more than 60 percent of this total was realized in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Cambodia.

In 14 countries, major mine action programs cleared more than 110 square kilometers of mined land and over 275 square kilometers of battle areas in 2006.

|

Country |

Mined area clearance (km2) |

Battle area clearance (km2) |

|---|---|---|

|

Afghanistan |

25.9 |

107.7 |

|

Angola |

6.9 |

0 |

|

Azerbaijan |

2.1 |

5.5 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

3.3 |

0 |

|

Cambodia |

51.9 |

0 |

|

Chad |

0.2 |

2.3 |

|

Croatia |

9.5 |

0 |

|

Iraq |

5.7 |

99.5 |

|

Laos |

0 |

47.1 |

|

Lebanon |

0.1 |

3.4 |

|

Sri Lanka |

1.7 |

5.2 |

|

Sudan |

1.3 |

6.4 |

|

Thailand |

1.0 |

0 |

|

Yemen |

1.9 |

0 |

|

Total |

111.5 |

277.1 |

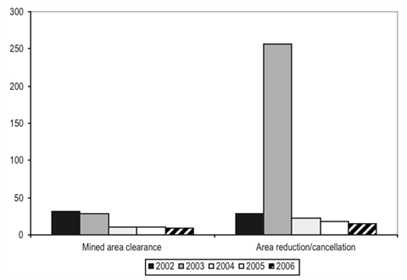

Progress in mine clearance in 2006 compared to the previous year, however, was uneven, with major differences in performance between mine action programs.

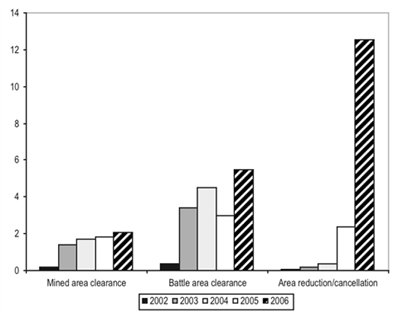

Mine Clearance in 2005 and 2006 (km2)

In Afghanistan decreased mine action funding in 2006 caused job layoffs which impacted on demining activity (although late-year contributions resulted in an overall increase in funding). Demining operators released 133 square kilometers of land in 2006, only 6 square kilometers (4.3 percent) less than the previous year. Although the overall decrease was small, it was achieved by changes in demining activity: the 25.9 square kilometers of mined areas cleared was down by one-third from 2005, mainly as a result of human resource cuts among Afghan NGOs. In contrast, battle area clearance, undertaken mainly by international NGOs unaffected by human resource cuts, increased by eight percent to 107.7 square kilometers.[5]

In Bosnia and Herzegovina 3.3 square kilometers of land was manually cleared in 2006, only two-thirds of the amount planned and substantially less than in 2005 and 2004 (when planning targets were also missed). The BiH Mine Action Center attributed the shortfall to major delays in EC tender procedures and failure to implement projects submitted to the International Trust Fund for Demining and Mine Victims Assistance.

There were increases in battle area clearance in 2006 from 2005 in several key countries, especially Iraq. In the south of the country, Danish Demining Group (DDG) was reported to have achieved a sharp increase in productivity, conducting battle area clearance on almost 100 square kilometers in 2006, compared with 6.3 square kilometers in 2005. The Regional Mine Action Center and DDG selected the area to be cleared on the basis of data collected by its community liaison and survey teams. Field operations are conducted entirely by national staff, working with protection provided by a 100-person security unit.

Battle Area Clearance in 2005 and 2006 (km2)

Mines and ERW remain a major humanitarian threat in certain countries, particularly where recent or ongoing conflict has caused new contamination or interrupted clearance of older mine/ERW contamination.[6] In Colombia, Iraq, Myanmar/Burma and the south of Somalia, for example, many lives continue to be claimed by mines and ERW (despite challenges in accurate data collection in all three countries). In Guinea-Bissau, new mine and ERW contamination occurred during a brief conflict in the north, where rebels from the Casamance region of Senegal planted mines to hold defensive positions and impede that country’s armed forces.[7] Israel’s widespread and indiscriminate use of submunitions against Lebanon in August 2006 caused hundreds of casualties subsequently.[8] In Afghanistan casualties remain stubbornly high despite one of the world’s most effective mine action programs.

In other countries, however, casualties have fallen significantly in recent years. In Cambodia, one of the world’s most affected nations, more effective targeting of clearance operations and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) on local priorities and heavily mined areas, including the massive K-5 mine belt, has contributed significantly to bringing the casualty rate down by many hundreds over the past two years.[9]

Clearance of Submunitions in Lebanon

The war between Israel and Hezbollah from 12 July to 14 August 2006 resulted in significant new contamination in Lebanon. The UN estimated that approximately four million submunitions had been fired on Lebanon, many in the last few days of the conflict, of which up to one million did not detonate. However, after 12 months of clearance activities the UN Mine Action Coordination Centre adjusted the estimate to about 500,000 unexploded submunitions remaining.

By the end of July 2007 the estimate of the area contaminated by cluster munitions had risen to 37.5 square kilometers. Yet, as of mid-August 2007, Israel had not provided detailed strike information on the type, quantity and location of cluster munitions used, despite numerous calls to do so by the UN Secretary-General and other senior UN officials.

By the end of 2006 some 3.4 square kilometers of affected areas had been cleared by international NGOs, the Lebanese Armed Forces and commercial operators, with the destruction of 94,544 submunitions. Eight clearance personnel were killed and 17 injured in clearance operations. In late August 2007 a Swedish clearance specialist was injured while clearing cluster munitions in Qaaqaiyat Al Jisr village in Nabatiyah region.

By the end of 2007 the UN in Lebanon expected that 30 square kilometers will have been cleared, leaving up to 10 square kilometers to be cleared in 2008.

Where mines and ERW are no longer a humanitarian crisis, they remain an obstacle to reconstruction and development, and critical to a nation’s stability as it transitions away from emergency.[10] Where fertile land is at a premium, such as in Southeast Asia, mine/ERW contamination hinders successful livestock-rearing and crop agriculture, both critical to a subsistence economy at the local level.[11] Mines and ERW can slow down road-building projects essential to the safe and rapid circulation of goods and labor, making them significantly more expensive, and can affect other important infrastructure. When casualty reduction is no longer the primary aim of demining, efforts to ensure demining supports the national reconstruction program–through priority setting and effective coordination–come to the forefront.[12] This is now the case in countries such as Angola, Ethiopia, Mozambique and Vietnam.[13]

Despite progress in demining made in recent years, many countries remain mine/ERW-affected. Landmine Monitor research indicates that 99 states and eight other areas are affected to some degree by mined and/or battle areas.[14]

Completion of Article 5 Obligations

There should be no confusion about the conditions required to fulfill Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty. Every State Party is required to identify and clear all mined areas under its jurisdiction or control within 10 years of becoming a party to the treaty.[15] As stated by Article 5, this includes, at a minimum, reviewing all areas suspected to contain antipersonnel mines and clearing, to international standards, every area that is confirmed to contain antipersonnel mines.[16] Thus, the inappropriately termed “permanent” marking does not constitute fulfillment of Article 5, although it is an interim requirement until mined areas are cleared.

The term “impact-free” does not appear in the Mine Ban Treaty, and is open to various interpretations, such as permanent fencing instead of clearance of some mined areas, or that there is no necessity to clear mined areas in uninhabited or inaccessible areas. Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty allows no such exceptions. The ICBL does not support the use of the term “impact-free.”[17]

The treaty does not state that a country must be “mine-free” to declare completion of Article 5 obligations.[18] After investigating suspected mined areas and clearing all confirmed mined areas, thereby meeting the Article 5 obligation, previously unknown mine contamination may be discovered in the future. For such eventualities, a residual clearance or EOD should be retained; newly discovered mined areas should be cleared promptly and reported fully in Article 7 transparency reports.[19]

Progress in Fulfilling Article 5 Obligations

While mine action programs in several States Parties have made significant strides towards fulfillment of Article 5 obligations, in too many others progress has been unacceptable. In the Nairobi Action Plan agreed in 2004 at the Review Conference, States Parties undertook to ensure that “few, if any” States Parties would be required to seek an extension to their Article 5 deadlines.

|

Completed clearance obligation |

Mined areas uncertain |

May meet 10 year deadline |

Unlikely to meet 10 year deadline |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Costa Rica |

Namibia |

Albania |

Argentina (Falkland Islands/Malvinas) |

|

FYR Macedonia |

Philippines |

Denmark |

|

|

Guatemala |

Djibouti |

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|

|

Honduras |

Ecuador |

||

|

Suriname |

France (Djibouti) |

Cambodia |

|

|

Jordan |

Chad |

||

|

Malawi |

Croatia |

||

|

Nicaragua |

Mozambique |

||

|

Rwanda |

Niger |

||

|

Swaziland |

Peru |

||

|

Tunisia |

Senegal |

||

|

Uganda |

Tajikistan |

||

|

Thailand |

|||

|

UK (Falkland Islands) |

|||

|

Venezuela |

|||

|

Yemen |

|||

|

Zimbabwe |

Four States Parties with 2009 deadlines, France, Niger, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela, have failed to initiate formal clearance operations, which may be considered a failure to respect the treaty’s requirement to clear mined areas “as soon as possible.” The mined area under the jurisdiction or control of France surrounds the La Doudah ammunition depot on French territory in Djibouti. In April 2007 France stated that all preparations were being made so that clearance could be achieved as soon as possible and, in any case, before France’s deadline of 1 March 2009. However, initiation of clearance operations has been significantly delayed, without any apparent justification. In the eight years that France has been a State Party, not one mine has been cleared from La Doudah.

Niger, with an Article 5 deadline of 1 September 2009, has made little progress since presenting a draft mine action plan for 2004-2006 during the February 2004 Standing Committee meetings.[21]

The UK, with a 1 March 2009 deadline, has mined areas on the Falkland Islands over which it exercises jurisdiction or control, which is disputed by Argentina. In June 2006 the UK stated that it was committed to fulfilling its treaty commitment. By mid-2007, however, the UK had still not initiated formal clearance operations, nor even developed a clear timetable and operational plan. Explaining the long delay since becoming a State Party in 1999, the UK stated that “this is a complex bilateral negotiation conducted against the background of a sovereignty dispute. This is a very complicated and intricate process.” However, the UK was not obliged to follow a bilateral process; there is no technical reason why the UK could not have begun demining earlier.

Venezuela, with a 1 October 2009 deadline, has publicly acknowledged that it is maintaining existing minefields for defensive use (which could constitute violation of Article 1 of the treaty as well as likely non-compliance with its Article 5 clearance deadline). At the April 2007 Standing Committee meetings Venezuela stated it had not made progress because it did not yet have a replacement for the antipersonnel mines used to guard naval bases. In July 2007 Venezuela’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirmed that an Article 5 extension request was being prepared.

The extent of residual contamination in Namibia and the Philippines is not known, therefore their obligations under Article 5 remain unclear.

Bosnia and Herzegovina (deadline 1 March 2009) acknowledged at the April 2007 Standing Committee meetings that it “will not be in a position to completely fulfill obligations stated under Article 5” and had started preparing an extension request. Its 2005-2009 mine action strategy aims only to reduce the mine/UXO risk and its associated socioeconomic impact “to an acceptable level.”

In view of the extent of its mine contamination, Cambodia’s medium-term vision is to be mine-impact free by 2012.[22] In April 2006 the Secretary General of the Cambodia Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority publicly affirmed that Cambodia will not meet the deadline and that “an extension will be required.” He said the government would make clear the duration of the extension required at the time of the request and would explain in detail the reasons for it.

Chad (deadline 1 November 2009) declared in April 2007 that although clearance of less than 10 square kilometers of the original estimate of 1,081 square kilometers “might appear derisory, it actually corresponded to area reduction of around 57 percent of the total,” namely 616.5 square kilometers of low, medium and high-impact areas. Nevertheless, limited survey information, slow progress in clearance and lack of funding indicate that Chad will not meet its Article 5 deadline.

Croatia warned in May 2006 that the chances of meeting its 1 March 2009 deadline were “very, very slim.” Since 1998 the Croatian Mine Action Center (CROMAC) has released some 613 square kilometers to local communities, as a result of mine clearance and general or technical survey. At the start of 2007 Croatia estimated that further general survey would lower the estimate of remaining contaminated land to about 1,000 square kilometers. In April 2007, Croatia informed States Parties that it had the capacity to clear about 40 square kilometers per year (although it has never achieved this amount).

Demining in Croatia 2002-2006 (km2)

Ecuador, despite an Article 5 deadline of 1 October 2009, has a mine action plan which schedules clearance to end in 2010. However, Ecuador has stated that it “would make all the necessary efforts to conclude operations in 2009….” It claimed that two elements were fundamental to its compliance with the Article 5 deadline: appropriate mechanical equipment and international financial support. An EC-funded project was said to enable Ecuador to “achieve the objective of declaring its national territory free from antipersonnel mines in 2010.”

In Jordan clearance of remaining minefields on its northern border with Syria, expected to take two years, had not started as of April 2007, thus casting doubt on its ability to meet the 1 May 2009 deadline. Previously, it was stated that, “Jordan not only seeks to become the first Arab country to be declared free of mines by 2009 but also aspires to become a regional hub for mine action in years to come.”

In Mozambique, with a 1 March 2009 deadline, the UNDP Chief Technical Advisor stated that, “Given all the scenarios surrounding the mine clearance progress so far and the task ahead, it is quite evident that the Government of Mozambique will request an extension on its deadline…possibly until end-2010.” In March 2007 Mozambique began making preparations for requesting an extension; if granted, this request was expected to be integrated into the 2007-2010 National Mine Action Plan.

In Nicaragua (1 May 2009 deadline) the Ministry of Defense has reaffirmed its desire to complete clearance operations. But Nicaragua sought US$5 million from international donors for demining in 2007 and 2008, without which it stated that demining would be extended into 2009 or 2010.

In Peru (1 March 2009 deadline) a 2006 monitoring mission for the EC-funded joint Ecuador-Peru demining project in the Condor mountains praised the good cooperation but noted management problems, especially in Peru, which had limited project implementation.

Senegal, despite protracted delays in setting up a demining program, stated in April 2007 its determination “to respect its undertakings set out in Article 5 of the Convention and to ensure the destruction of antipersonnel mines under its jurisdiction or control within the prescribed deadlines, i.e. March 2009, to the extent possible.” A June 2007 agreement with UNDP should help Senegal to eventually meet its obligations.

Thailand (1 May 2009 deadline), after seven years of demining, had cleared and reduced 20 square kilometers, less than one percent of the suspected hazard area identified in 2001 and four percent of the 500 square kilometers believed by the Thailand Mine Action Center (TMAC) to be contaminated. At the April 2007 Standing Committee meetings Thailand stated that “despite our very best efforts, an extension request for mine clearance may be inevitable.” It added, “this extension request will by no means set back our commitment and efforts to clear mines within our territory as soon as is realistically possible.” TMAC has estimated it needs approximately $12 million for clearance operations over the next five years. It expects Thailand will submit a request for extension of its Article 5 deadline by March 2008.

Uganda, with a 1 August 2009 deadline, has been slow to initiate a mine action program. Clearance did not start until 2006 but momentum increased considerably during the year and in April 2007, “It is anticipated that by 2009 Uganda shall have adequate capacity to carry out technical surveys, explosive disposal ordnance and clearance capacity to enable the Uganda Mine Action Centre to destroy all anti-personnel mines in the identified mined areas under Uganda’s jurisdiction.” The center’s director added that the mine action plan is dependent on “the successful outcome of the peace negotiations and the eventual end of conflict. The prospective end-date of fulfilling obligations in Article 5 is dependent on this factor.”

Yemen (1 March 2009 deadline) has claimed that because some mines are located deep below shifting sand they cannot be removed with existing technology. Its mine action strategy is to ensure “all communities classified as high and medium impact, and 27 percent of the most critical low-impacted areas (147 square kilometers) are cleared by the end of March 2009.” In its most recent Article 7 report, Yemen said it plans to permanently mark 16 of the remaining minefields, a strategy that falls short of the full requirements of the treaty.

Zimbabwe (1 March 2009 deadline) has a five year strategic plan that envisages clearance of all mined areas by 2009, but the demining progress is far behind schedule, with only about 40 percent of mined areas cleared by April 2007. The Director of the Zimbabwe Mine Action Centre stated that, “Zimbabwe will not make it to the 2009 deadline…as shown by the extent of surveyed minefields and those not yet surveyed. We are in the process of preparing a request for the extension of our deadline which we will forward before February 2008. Under current funding it may take not less than 20 years to complete.”

Criteria for Reviewing Article 5 Extension Requests

A State Party’s performance in seeking to fulfill its Article 5 obligations should be among the criteria for judging extension requests. The ICBL fully supports the process established at the Seventh Meeting of States Parties and encourages States Parties to abide by these procedures, including use of the recommended template and submission of requests nine months ahead of the Meeting of States Parties where a decision will be taken.[23] In general, no automatic or blanket extension requests should be granted to any State Party. Where there is a well-founded case for an extension, the minimum possible period should be granted and progress during the extension period should be subject to the active oversight of States Parties. Where there is evidence that the requesting party did not make a sufficient effort to meet its initial deadline, this fact should be clearly stated by the other States Parties when rendering their decision.

The ICBL believes that three principal factors should be taken into account when reviewing a request for an extension:

- There should be evidence of a commitment by the requesting State Party to implement Article 5 “as soon as possible.” Such evidence could include the establishment of a national mine action program (including the necessary enabling legislation); creation or contracting and deployment of an appropriate demining capacity as soon as possible after becoming a State Party; increases in demining capacity and productivity over time; national funding for the mine action program, with commitments to increase this; reporting the amount of land released relative to the original amount suspected to contain antipersonnel mines; and efforts to draw up a comprehensive inventory of mined areas containing antipersonnel mines, as required by Article 5, paragraph 2.

- The requesting State Party should submit a strategic plan for demining operations that justifies the period of the requested extension.[24] Such a plan should be realistic and accurately costed. It should detail precise undertakings by the requesting State Party, including a plan for the mobilization of resources from national and international sources. It should reflect national and development priorities, clearing first where the need is greatest. Any State Party that does not provide such a plan should be required to develop one and submit it to the next Meeting of States Parties, at which time the extension request should be reconsidered.

- States Parties should take into account extenuating circumstances that have been impeding the full implementation of Article 5. States that have an ongoing internal conflict, or climatic or environmental obstacles to demining, or especially large suspected mined areas should not be judged in the same light as countries that have not had such special challenges to overcome. A decision should also take into account the availability of international cooperation and assistance.

Demining programs continue to allocate scarce resources to conduct operations on land which is then discovered not to be contaminated.[25] As a result, land release principles have come to the forefront of demining programs over the last five years. At the Standing Committee meetings in April 2007 three presentations addressed the topic.[26] GICHD noted that, “General assessments and impact surveys have led to large areas of ‘suspect’ land, but in reality much less is actually mined.”[27] As a rule of thumb, between 5 and 20 percent of the area originally suspected to be hazardous turns out to be actually affected.[28] Enhanced impact survey procedures are, however, now minimizing this discrepancy.[29]

In Angola the Landmine Impact Survey was completed by May 2007 for all 18 provinces. The draft final report identified mine/ERW contamination in 1,968 “localities,” and concluded that some 2.4 million people were impacted. The survey generated an upper estimate of 1,239 square kilometers of suspected hazard areas, with a lower estimate of 207 square kilometers (assuming that areas would be reduced based on more precise later assessments).

Surprisingly, there is not yet an International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) definition of land release or area cancellation, although a “Big Bang” project being conducted by the Marshall Legacy Institute in the US with support from the Survey Action Center is seeking to generate possible definitions.[30] There are also no standards or guidelines for appropriate procedures.[31] At the April 2007 Standing Committee meetings the ICBL, while strongly supporting the appropriate use of area cancellation and area reduction as techniques to release land, put forward basic principles to ensure that the needs of affected communities are at the forefront of any shifts in mine action strategy, as follows:

- suspect hazardous areas found to contain antipersonnel mines must be cleared to IMAS or national standards in accordance with a country’s legal obligations;

- area reduction or cancellation methodology must be based upon an objective assessment using fixed criteria rather than a subjective decision made by survey teams;

- area reduction or cancellation methodology should be understood and accepted by local government representatives, the intended beneficiaries and their representatives;

- information on which decisions are made to release land other than through clearance must be carefully crosschecked with a range of key informants to minimize bias and error;

- all activities leading to the decision to release a specific area of land must be carefully documented, with decisions made in a transparent manner;

- the process of land release must be inclusive and participatory; it must be approved by the owner/s of the land, community representatives, national authorities and the national mine action center based upon review of the documented methods; and the handover process should include an explanation of the method/s used to release the land and the potential residual risk;

- the demining process leading to land release must follow national standards and standing operational procedures;

- any subsequent discovery of a mine or ERW on land that has been released must lead to an investigation, reassessment and possible clearance of the area;

- States Parties are encouraged to include in each Article 7 report the extent of land release and methodologies employed.

An increasing number of countries are realizing the importance of efficient land release, with good results, as comparison of 2005 and 2006 data reveal.

Area Reduction and Cancellation in 2005 and 2006 (km2)

Three countries, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia and Yemen, reported releasing more than 100 square kilometers of suspected hazardous areas in 2006 through area reduction and area cancellation. Afghanistan and Iraq achieved release of more than 100 square kilometers due largely to battle area clearance.

In Cambodia productivity accelerated sharply in the past two years with greater efficiency achieved by application of a toolbox approach applying different clearance assets and methodologies to deal with different tasks and types of terrain, as well as by official recognition of the need to reclassify land already in productive use. The three demining NGOs in Cambodia increased the amount of land cleared by 63 percent to 30 square kilometers in 2005 and by a further 15 percent to 35 square kilometers in 2006. The amount of land identified in the Landmine Impact Survey as suspect and released after identification in further surveys as under cultivation or in productive use more than tripled in 2006 to 303 square kilometers.[32] In the first half of 2007 the three NGOs area reduced a further 268 square kilometers.

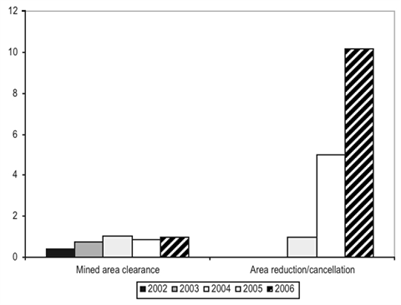

In Azerbaijan the pace of demining has increased significantly, largely due to the introduction in 2006 of a new integrated area reduction methodology that combines manual deminers, mine detection dogs and extensive use of mechanical assets.

Demining in Azerbaijan 2002-2006 (km2)

In Laos the national operator achieved big productivity increases after reviews of its operations and clearance methodologies; it cleared nearly 21 square kilometers in 2006, one-third more than the previous year. Productivity gains look set to continue as UXO Lao completes its conversion from the metal-free or demining methodology used over the past decade to battle area clearance consistent with an environment where the dominant threat is from UXO, and it adopts a more selective, evidence-based approach to tasking. In the first half of 2007 it cleared more than 16 square kilometers, more than in the whole of 2005. The National Regulatory Authority commissioned a risk management and mitigation model to lay the basis for “a new approach to addressing the Lao PDR contamination problem” that would set new standards for assessing risk and clearance priorities, tasking operators and releasing land to the community.

Thailand, with its impending treaty deadline, has also sought to accelerate clearance and release of land since 2005 by emphasizing area reduction and the need for technical survey.

Demining in Thailand 2002-2006 (km2)

Developments in Demining

Mechanical demining assets have been used increasingly to improve demining productivity. At a minimum, ground preparation machines can significantly improve the productivity of manual deminers for a relatively small outlay. Following a GICHD study, the use of machines has increased, especially for technical survey and sometimes as the primary clearance tool, and especially in antipersonnel minefields.[33]

Mine detection dogs remain a controversial issue. Operators such as Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) and RONCO make widespread use of dogs and firmly believe in their effectiveness and efficiency. Since late 2005 NPA has helped the mine action program in Ethiopia to incorporate a canine component to increase the program’s performance.[34] In contrast, HALO trialed mine detection dogs several years ago and decided not to use them.

There has been a potentially significant improvement in the effectiveness of the deminer’s basic tool, the mine (metal) detector. Since early 2006 HALO has tested an enhanced detector that uses ground penetrating radar (GPR) to discriminate between mines and metal clutter. The Handheld Standoff Mine Detection System (HSTAMIDS) is a modified Minelab F1A4 detector with ground compensation and an integrated GPR system. It was developed for the US military and has seen service in Afghanistan and Iraq with the US Army.[35] In tests in Cambodia between April and November 2006 HALO found that the detector rejected 85 percent of metal clutter and cleared on average 200 square meters a day, finding a total of 1,104 mines with only two Type 72A mines mis-detected. Although the HSTAMIDS detector required additional training, once deminers were competent in its use clearance rates were found to be 10 times those achieved by standard detectors.

Community liaison, part of the IMAS definition of both mine risk education and demining and pioneered by Mines Advisory Group in the 1990s, continues to demonstrate its ability to ensure the speedy and appropriate use of released land. Successful handover procedures are sometimes considered an optional extra by programs even though the failure to conduct them can mean that part or all of land, cleared at high cost, remains unused.[36]

Mine Action by Non-State Armed Groups

NSAGs and linked organizations carried out limited mine clearance and, to a greater extent, explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) operations during the reporting period.[37] Examples include:

- in Lebanon Hezbollah claimed that some of its members undertook clearance of up to several thousand submunitions after the conflict in August 2006;

- in Sri Lanka in early to mid-2006 the LTTE-linked TRRO Humanitarian Demining Unit continued clearance activities, but its work halted in September 2006 due to a freeze on its financial resources by the Sri Lankan government and renewed armed conflict; and,

- in Western Sahara the Polisario Front assisted the UN mission in marking and disposing of mines, UXO and expired ammunition. Landmine Action conducted training of a national staff team of 12 demobilized Polisario army engineers in survey, battle area clearance, EOD and medical procedures.

- in Abkhazia demining continued to be carried out primarily by 250 local staff under HALO management, while the CIS peacekeeping force provides EOD and mine clearance on request;

- in Kosovo the Office of the Kosovo Protection Corps Coordinator is responsible for mine action and all matters related to EOD, under the direct authority of the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General; during 2006 demining was conducted by the Kosovo Protection Corps, KFOR (international forces), Mines Awareness Trust and HALO;

- in Nagorno-Karabakh clearance is carried out primarily by HALO, while the Karabakhi Department of Emergency Situations conducts limited EOD;[38]

- in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, the Palestinian police EOD teams are reported to have engaged in limited clearance operations;

- in Somalia, Puntland’s regional authorities reported undertaking limited EOD;

- in Somaliland the police carried out spot EOD tasks while most demining and EOD was undertaken by HALO and DDG under the auspices of the Somaliland Mine Action Center; and,

- in Taiwan the army established its first group of military deminers in mid-2006 to undertake humanitarian demining, prompted by the Antipersonnel Landmines Regulations Act and in a bid to accelerate clearance. The demining unit, composed of 18 volunteer soldiers, completed a 10-week demining and EOD training course conducted by a commercial demining company and had cleared 31,000 square meters and disposed of 1,163 mines by November 2006.

Increasing importance is accorded to national ownership of mine action programs.[39] While some national programs have worked for several years without outside technical assistance, others have been supported by international advisors for more than a decade but are still not nationally sustainable or fully owned.[40]

A nationally owned program is not one that simply exists independent of foreign technical advisors. It also demands that the state exert effective political, financial and technical ownership of mine action, including:

- national mine action legislation;

- ability to mobilize resources to ensure the program’s sustainability, in particular from national sources;

- rational and realistic strategic mine action plans integrated with national development objectives; and,

- national standards and standing operating procedures optimizing both safety and efficiency.

Research suggests that civilian management of a mine action program is generally more effective than the military, although when a program has downsized to a residual capacity this may be best housed within the Ministry of Defense.[41] IMAS recommends that a national mine action authority, normally an interministerial body, conduct oversight of mine action. This helps the government take charge of the program and ensures key stakeholders (such as the ministries of agriculture, education, health and interior) are actively engaged in setting the priorities.

Daily coordination of the program is often carried out by a mine action center, usually a para-state entity. This includes tasking implementing organizations, conducting quality management and drafting annual workplans and national mine action standards for the program.

During this Landmine Monitor reporting period (since May 2006), changes in the management of mine action programs occurred in several countries:

- in Colombia on 12 June 2007 a presidential decree transferred all functions of the Antipersonnel Mines Observatory to the new Presidential Program for Integrated Action Against Antipersonnel Mines;

- in Lebanon the National Demining Office, part of the Lebanese Armed Forces, drafted a mine action policy in which it was responsible for managing the mine action program which was approved in May 2007. The NDO was renamed the Lebanese Mine Action Center under the command of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations of the Lebanese Armed Forces; and,

- in Uganda a mine action policy was formally adopted in October 2006, pending cabinet approval. In April 2007 Uganda announced that mine action would move into a nationally executed program during the year, and Uganda appealed to UNDP to quicken the process.

Lack of security proved a major challenge for mine action in Afghanistan and Iraq, and an increasing problem in Sri Lanka during 2006-2007.

In Afghanistan security for deminers continued to deteriorate, particularly in the south and east, underlined by a Taliban attack in April 2007 on a RONCO team that was traveling with armed protection in western Farah province; three deminers, three guards and a civilian passer-by were killed. On 4 August three deminers from local operator MDC were abducted by Taliban forces in southern Kandahar province and later found murdered.[42]

In Iraq insecurity not only severely curtailed the ability of demining organizations to deploy but also penetrated the Baghdad headquarters staff of the National Mine Action Authority, whose director was kidnapped in May 2007.

In Sri Lanka intensification of fighting from 11 August 2006 brought demining operations to a standstill for about six weeks, and had other adverse effects on operational capacity. Operators faced threats to the security of their deminers, who include a majority of Tamils; there were staff abductions; many deminers working in LTTE-controlled territory left to join “local security forces;” operators faced tight restrictions moving Tamil deminers to tasks in different districts; and access to explosives for destroying mines and ERW was denied. In August 2007 DDG suspended operations in Jaffna after one of its deminers was shot dead by unknown attackers on his way to work and another deminer was wounded.[43]

Fear of attack curtailed some clearance activities. In Sudan the Lord’s Resistance Army from Uganda was reported to have ambushed a team from the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action near Juba, killing two deminers; as a result, a commercial demining firm suspended activities. Fear of attack or conflict in the south of Sudan and in Darfur led to some temporary suspensions of clearance operations. According to the UN, during late 2006 and early 2007 newly laid antivehicle mines injured two demining staff and others in the Temporary Security Zone separating Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Data Gathering and Inadequate Reporting

The quality of mine action planning is only as good as the data on which it is based and the quality of data analysis. Despite many years of technical assistance by a variety of actors, the gathering and reporting of demining data by national programs remains highly variable. Landmine Monitor believes there is a need to distinguish systematically between battle area clearance and mine clearance, between AXO and UXO, and between destruction of cleared and stockpiled mines. Too few programs are able to generate and provide this data.

There continues to be reporting of “cleared” areas where little or no actual clearance has taken place. For example, in Mozambique the National Demining Institute reported that one commercial operator had “cleared” in 2006 the massive total of over 3.1 square kilometers without destroying a single mine or item of UXO. Physical clearance and release by other means must be clearly distinguished if mine action programs are to provide an accurate account of their achievements.

Challenges

The tools and techniques for effective and efficient mine action are available, despite some setbacks in 2006. The challenge for the international community is to finish the job. Meeting the needs of affected populations means ensuring a balance of resources between humanitarian and developmental mine action operations, releasing land swiftly and safely, and reporting accurately on achievements and obstacles. This will require political will, focus and commitment from affected states, donors and operators through 2009 and beyond.

[1] Demining covers the range of activities which lead to the removal of the threat from landmines and ERW, notably survey, risk assessment, mapping, marking, clearance, and the handover of cleared or otherwise released land. Clearance is only one part of the demining process. ‘Demining’ and ‘humanitarian demining’ are considered synonyms under the international mine action standards (IMAS). Explosive remnants of war include unexploded ordnance (UXO) and abandoned explosive ordnance (AXO).

[2] Especially significant is the absence of data on Iran, which has a huge mine clearance program.

[3] In 2005, only 260 square kilometers of land release was recorded.

[4] This and other tables and charts in this section do not include the results of all mine action programs in the world in 2006. Major mine action programs for which reliable data was available were selected. For example, Iran has previously reported very large clearance figures but it has not been possible to reconcile different data sets. The Sudan program also assessed 7,010 kilometers of roads of which it demined 814 kilometers. Yemen does not distinguish between battle and mined area clearance in its statistics.

[5] Brief summaries of mine action in several countries are given in this section. For more information and sources, see reports for each country in this edition of Landmine Monitor.

[6] Not every conflict leads to mine contamination. For example, it had been feared that the combat in Côte d’Ivoire would generate a new mine problem, but this does not appear to be the case.

[7] In this regard, the UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) reported that the UN’s Framework for Mine Action Planning and Rapid Response was thoroughly reviewed and revised in 2004 and was put to the test twice in 2006, first in the emergency in Guinea-Bissau in March. The response required inter-agency planning and mobilization of financial, human and technical resources. The second and larger effort under the Framework in 2006 involved the significant surge in mine action capacity required to respond to the humanitarian crisis in South Lebanon. Support from donors enabled UNMAS to react to the situation in Lebanon “in a timely manner while also mobilizing dedicated resources.” See UNMAS, “2006 Annual Report,” New York, p. 21.

[8] One of the few positive outcomes of the suffering inflicted on Lebanon’s population has been lessons learned by the demining community on the successful–and safe–disposal of a variety of submunitions within an emergency clearance program. See, for example, the Technical Note for Mine Action “Clearance of Cluster Munitions (Based on Lebanon Experience),” under development in mid-2007 as part of the IMAS.

[9] The K5 mine belt was created by the Vietnamese-backed government of Cambodia to deter resistance after the Khmer Rouge was ousted from government in 1978; the mine belt was later augmented by ‘nuisance mining.’ It stretches 700 kilometers along the Thai border, and has been responsible for the large majority of recent mine casualties in Cambodia. There was a sharp fall in the number of mine and ERW casualties in Cambodia from 875 in 2005 to 450 in 2006, and 88 percent of mine casualties occurred in just four provinces on the border with Thailand; UXO casualties consistently account for more than half the total casualties in Cambodia. The sharp rate of decline continued in 2007.

[10] The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) has developed principles and guidelines for linking mine action with development. In the June 2007 draft, four principles are outlined for a national mine action authority: 1, take the lead in ensuring the country fulfills its international legal obligations; 2, demonstrate ownership of mine/ERW contamination problem; 3, ensure the integration of mine action with national, sector or subnational development plans, where relevant, to ensure mine action is aligned with development; and 4, ensure information sharing and collaboration across sectors and among key actors. See, “Linking Mine Action and Development: Guidelines for Mine-Affected States,” www.gichd.org.

[11] For example, although nationally in Ecuador the socioeconomic impact is small, mine/ERW contamination restricts and endangers subsistence livelihoods in the sparsely populated border areas; particularly affected are the indigenous Shuar and Achuar tribes which are prevented from accessing large tracts of their traditional farming and hunting land.

[12] For example, demining in the provinces of El Oro, Loja and Morona Santiago in Ecuador, and in Amazonas department in Peru, in the affected border area between the two countries, were said to enable the construction of three major roads and an international bridge which are expected to directly benefit 500,000 inhabitants.

[13] An evaluation of the mine action program in Ethiopia in 2006-2007 concluded that the Ethiopian Mine Action Office “has performed increasingly well since its establishment. Its demining operations have made a substantial contribution to the resettlement and rehabilitation efforts in the war-affected districts (‘woredas’) of Tigray and Afar, delivering significant socio-economic benefits for those regions and promoting Ethiopia’s post-war recovery.”

[14] The 99 countries (States Parties in bold) and eight areas (italicized) affected by mined and/or battle areas are: Abkhazia, Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Bhutan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Chechnya, Chile, China, Colombia, Republic of Congo, DR Congo, Cook Islands, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Denmark, Djibouti, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, France (Djibouti), Georgia, Greece, Guatemala, Guinea-Bissau, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Kosovo, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Latvia, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Lithuania, FYR Macedonia, Malawi, Mauritania, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar/Burma, Nagorno-Karabakh, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, North Korea, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Panama, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Russia, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, Somaliland, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Swaziland, Syria, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, United Kingdom (Falklands), Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam, Western Sahara, Yemen, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Landmine Monitor has added ERW-affected countries/areas to its previous list of mine-affected countries/areas, and made other changes: the US has been removed (although it still has considerable contamination in training areas); Bhutan has been added, as have Cook Islands and Vanuatu (both have World War II contamination); other countries with ERW contamination are not included if they are not, or not known to be, impacted by that contamination. Bangladesh, Djibouti and Honduras have a residual threat from landmines although are not mine-affected in the sense of Article 5 of the Mine Ban Treaty. In addition, Argentina claims to be mine-affected by virtue of its contested claim of jurisdiction over the Falkland Islands/Malvinas.

[15] Jurisdiction covers all of a country’s “sovereign” territory, including non-metropolitan territories and other overseas dependencies, and control encompasses other land it occupies or otherwise exercises authority over, even if that occupation is contested or considered unlawful. Either jurisdiction or control engages legal responsibility; both are not required. Areas within a State Party’s jurisdiction, but not its effective control (such as areas occupied by NSAGs) are also included in this obligation, though international law makes allowance for a state’s inability to intervene in such circumstances.

[16] The UN Development Programme (UNDP) Completion Initiative seeks to accelerate mine action in countries where a concerted effort and an investment of up to $10 million would solve the landmine problem within stipulated deadlines. Although the Completion Initiative aims to focus on the antipersonnel mine problem in an attempt to meet treaty obligations, it also strives to develop national clearance and survey capacities to undertake ERW clearance and national ownership of the mine action program. National capacity would be equipped and trained to address any residual mine problem that may occur after treaty deadlines have been met. Email from Melissa Sabatier, Mine Action and Small Arms Unit, Bureau for Crisis Prevention and Recovery, UNDP, 22 August 2007.

[17] ICBL, “Views on Fulfillment of Article 5 Obligations,” May 2006,

www.icbl.org/content/download/22248/413788/file/Article5Fulfillment-May2006.doc.

[18] Although in June 2004 clearance was said to be finalized in Honduras, the Organization of American States (OAS) noted in the same year that certain regions would remain at risk of future mine incidents, especially in border areas, because of the nature of the original mine-laying and environmental factors. Available information indicates that Honduras has complied with the requirements of Article 5, but it cannot claim to be “mine-free” and a residual demining capacity will continue to be required.

[19] Thus, for example, although there may be residual mines in Djibouti (in addition to the mines laid by France around its ammunition depot at La Doudah), since the mine action program has cleared all known mined areas, the existence of any residual mines will not prevent a declaration of completion of the Article 5 obligation.

[20] The “mined areas uncertain” column includes States Parties where the existence and extent of mined areas is still unclear, requiring further survey in accordance with Article 5, paragraph 2. Argentina claims jurisdiction over the Falklands Islands/Malvinas and declared in Article 7 that it is mine-affected.

[21] Niger did not attend the Standing Committee meetings in 2005, 2006 or 2007 to provide an update on its mine clearance efforts or request assistance from other States Parties.

[22] National Mine Action Strategy, Third Edition, CMAA, Phnom Penh, March 2005, p. 7.

[23] See, ICBL, “Recommended criteria for judging extension requests,” Geneva, April 2007,

www.icbl.org/news/isc07docs/extreq.

[24]Normally, this should be part of a broader strategic plan covering all aspects of mine action.

[25] For example, GICHD, “A Study of Mechanical Application in Demining,” Geneva, May 2004, p. 57, table 5, which showed that of 290 square kilometers of land claimed to have been cleared only 2.09 percent was actually contaminated.

[26] Presentations by CROMAC, GICHD and Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA); see, www.apminebanconvention.org.

[27] Presentation by Ian Mansfield, Operations Director, GICHD, “Land Release and Risk Management Approaches,” Standing Committee on Mine Clearance, Mine Risk Education and Mine Action Technologies, Geneva, 26 April 2007.

[28] The extent of reduction may, on occasion, be even more. In 1996 Croatia estimated that 13,000 square kilometers of its territory were mine-affected. As of end-2006 this was down to 1,044 square kilometers with further reduction likely. Presentation by Miljenko Vahtarić, Assistant Director, CROMAC, Standing Committee on Mine Clearance, Mine Risk Education and Mine Action Technologies, Geneva, 26 April 2007. In Mauritania a Landmine Impact Survey in 2006-2007 successfully reduced the suspected affected area from an (admittedly highly unrealistic) estimate of one quarter of the national territory (310,000 square kilometers) to only 76 square kilometers, with ongoing technical survey as of 2007 reducing it further.

[29] In Angola, for example, prior to the completion of the Landmine Impact Survey (LIS) estimates of the total size of contaminated areas reached as high as 400,000 square kilometers. As of May 2007 the LIS had provided an upper estimate of 1,239 square kilometers of contaminated area, with a lower estimate of 207 square kilometers based on a new visual inspection protocol adopted by the Survey Working Group and piloted by HALO.

[30] Email from Bob Eaton, Director, SAC, Washington, DC, 29 August 2007. The project is trying to identify costs for the clearance of remaining mined areas in affected countries.

[31] Area reduction is defined broadly as “the process through which the initial area indicated as contaminated (during any information gathering activities or surveys which form part of the GMAA process) is reduced to a smaller area.” IMAS 04.10, Second Edition, 1 January 2003 (Incorporating amendment number(s) 1, 2 & 3), Definition 3.16; see: www.mineactionstandards.org/imas.htm. The ICBL uses different definitions, although there is no direct contradiction: “area cancellation” describes the process by which a suspected hazardous area is released based solely on the gathering of information that indicates that the area is not in fact contaminated; it does not involve the application of any mine clearance tools. “Area reduction” describes the process by which one or more mine clearance tools (for example, mine detection dogs or mechanical demining equipment) are used to gather information that locates the perimeter of a suspect hazardous area; those areas falling outside this perimeter, or the entire area if deemed not to be mined, can be released.

[32] In May 2006 the Cambodian government adopted a risk reduction strategy of reclassifying land identified as suspect in the LIS but already reclaimed by the community. Such land is not considered cleared but viewed as “land where the threat has been reduced to a level at which, unless particular circumstances exist (such as for infrastructure), further mine clearance should not be considered.”

[33] In South Sudan, for instance, NPA used a MineWolf machine and sometimes achieved over 10,000 square meters per day in 2006. In Somaliland the HALO Trust found that the introduction of mechanical assets to its program doubled its clearance output.

[34] NPA’s average mine detection dog (MDD) production rates in Ethiopia have consistently remained at the high end of what NPA considers safe, approximately 800-1,000 square meters per dog per working day. Between the start of operations in December 2005 and the end of 2006, NPA dogs cleared more than one square kilometer of land. NPA runs a Global Training Center for MDD in Bosnia and Herzegovina to provide its programs with trained dogs.

[35] See, for example, US Department of Defense, “Handheld Standoff Mine Detection System – HSTAMIDS,” Presentation to the Meeting of National Directors and UN Advisors, Geneva, 21 March 2007, www.mineaction.org.

[36] See, for example, B. Pound et al., “Departure of the Devil: Landmines and Livelihoods in Yemen,” Volume I, Main Report, GICHD, Geneva, 2006, www.gichd.org, which describes the situation in Yemen. Community liaison is part of task impact assessment by NPA.

[37] However, some demining operations were also attacked by NSAGs. For example, in Senegal government deminers were attacked by rebels, killing two and injuring 14 others. See later section, Demining Security.

[38] From 2002 to 2006 HALO released 93.61 square kilometers in Nagorno-Karabakh by mine clearance, battle area clearance and area reduction/cancellation. There has been an increase in clearance every year, due to “careful planning, expansion of the clearance capacity and technical survey.”

[39] Capacity development initiatives supported by UNDP, such as the Middle and Senior Management courses, and delivered by Cranfield Mine Action (now the Resilience Centre, Cranfield University) and James Madison University, as well as the regional training centers in Benin and Kenya, constitute significant opportunities for mine action programs around the world.

[40] Examples of nationally owned mine action programs are Azerbaijan, Croatia and Yemen. Mine action programs which continue to be reliant on international support include Afghanistan, Cambodia and Mozambique.

[41] A number of programs have been changing from military to civilian management of mine action. For example, in Mauritania on 20 November 2006 the Minister of Economic Affairs and Development signed a decree transferring the mine action program into his ministry’s responsibility from the Ministry of Defense. The new coordinating body, the National Humanitarian Demining Program for Development, will be responsible for planning, coordination and implementation of demining activities and for their integration with development efforts. In Thailand, despite a military coup in late 2006, moves to transform the Thailand Mine Action Center from a military-led undertaking to a civilian agency under the Prime Minister’s Office continued in 2007.

[42] “Killing of de-miners suggests change in Taliban tactics,” IRIN, 7 August 2007, www.alertnet.org. This occurred after the report on Afghanistan in this edition of Landmine Monitor was completed.

[43] “Demining in Jaffna suspended following killing of NGO staffer,” Sibernews Media, 22 August 2007, www.sibernews.com. This occurred after the report on Sri Lanka in this edition of Landmine Monitor was completed.