Landmine Monitor 2007

Mine Risk Education

Mine risk education (MRE) aims to prevent death and injury from landmines and explosive remnants of war. In this Landmine Monitor reporting period (since May 2006) several evaluations of MRE attributed reductions in casualties in part to effective MRE, for example in Cambodia and Laos.

In addition to its role in reducing casualties, MRE assists in the planning and prioritization of mine action by mobilizing mine-affected communities to report on dangerous areas, and helps to identify mine survivors and their needs. MRE is also a good tool to advocate for a ban on landmines. MRE is, therefore, an integral component of mine action. In 2006-2007 the positive trend of recent years continued, with MRE increasingly integrated into other forms of mine action and broader disciplines in many countries.

However, in crisis situations where humanitarian clearance cannot be undertaken, MRE may be the only immediate response available. In these cases, as well as providing information on risk avoidance, MRE teams play a vital role in gathering information from local people to establish the extent and nature of contamination. Local journalists may receive MRE in order both to spread risk-avoidance messages and to improve the accuracy of their reporting on casualties and the type of explosive devices. In 2006-2007 MRE operators responded with “emergency MRE” to several crisis situations, notably in Lebanon after the July-August 2006 war and the additional threat caused by unexploded cluster submunitions.

Methods used in the provision of MRE include a variety of “activities that seek to reduce the risk of injury from mines/UXO by raising awareness and promoting behavioral change; including public information dissemination, education and training, and community mine action liaison.”[1] Community-based approaches continued to be promoted worldwide in 2006. An April 2007 mine action guide noted that, “The most successful efforts to achieve mine-safe behaviour use a variety of interpersonal, mass media and traditional media channels. These include individuals who practice mine-safe behaviour, local influential people and community leaders, radio and television networks, community training programmes and – most important of all – those that encourage communities to participate in planning, implementing, monitoring and improving their own interventions.”[2]

While accidental exposure to risk from mines and ERW may be reduced by the effective provision of information, intentional risk-taking behavior poses greater challenges as it is often driven by economic necessity. In some countries people collect mines and explosive remnants of war to sell as scrap metal. In many cases daily livelihood activities such as collecting firewood, farming and grazing animals, or trading with neighboring villages, lead people to knowingly enter dangerous areas. To address intentional risk-taking, a wider set of responses is needed, including poverty-reduction measures and working with local stakeholders to identify alternative income-generating activities. This may involve integration of MRE with other humanitarian and development activities.

MRE Programs in 2006-2007

Landmine Monitor recorded MRE activities in 63 countries in 2006 and the first half of 2007, three more than in 2005.[3] Forty-four of the countries with MRE were States Parties to the Mine Ban Treaty.[4] Nineteen are not party to the treaty.[5] There were also MRE programs or activities in seven of the eight other areas covered by Landmine Monitor.[6]

The total number of direct MRE recipients increased to 7.3 million people in 2006, from 6.4 million in 2005.[7] As in past years, the global total is only an estimate based on many sources providing information to Landmine Monitor. The total of 7.3 million does not include recipients of MRE delivered by mass media, but many could be individuals receiving MRE from multiple sources or on several occasions; there may also be multiple counting by some agencies. Five countries accounted for nearly four million MRE beneficiaries: Afghanistan, Vietnam, Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Sudan.[8]

No mine risk education was recorded in 36 countries and one area affected by mines or ERW. In some cases, no initial assessment of the need for MRE was undertaken; in some, formal MRE may not be necessary. Of the 36 countries, 26 were States Parties.[9] The Mine Ban Treaty requires that States Parties report on measures taken “to provide an immediate and effective warning to the population” of mined areas. As of July 2007, 28 States Parties had reported on MRE in their Article 7 reports, five more than last year.[10] A voluntary Article 7 report from Morocco (not a State Party) also included MRE. States Parties that either do have or would be expected to have MRE but did not report on MRE in their Article 7 reports included Algeria, Belarus, Cambodia, Namibia and Ukraine.

New MRE activities were recorded in 34 countries, a notable development from 2005 (28 countries). For the first time, MRE was recorded in Cyprus, Libya and Morocco; in other countries, there were new MRE providers, significantly expanded activities, and/or new geographic areas covered. Of the 34 countries, 25 were States Parties and nine states not party to the treaty.[11] There were also new MRE activities in Somaliland, in Western Sahara and for the first time in Taiwan.

Adequacy of MRE

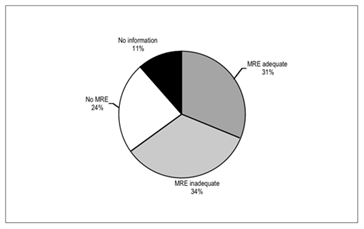

MRE operators stress that the quality and impact of MRE is as important as the number of beneficiaries. Landmine Monitor has attempted to estimate the adequacy of MRE activities in this reporting period, based on research for country reports in this edition of Landmine Monitor, whilst cautioning that such estimates are approximate and provisional. Targeting specifically those communities at risk, providing context-specific information and searching jointly for realistic alternatives to risk-taking behavior seem obvious priorities for good MRE but are still not the norm in many programs. Often a lack of accurate and current data to fully understand the threat at the local level hampers MRE.

“Adequate” means that a program was in place capable of providing MRE appropriate in scale and nature to the actual mine/ERW threat in that locality. In countries or areas with a limited mine/ERW problem, a limited MRE program may be adequate as long as the number of casualties remains very low or zero. However, in most of these countries additional MRE capacity would be justified to achieve a more comprehensive provision of services.

Of the 99 countries and eight areas affected by mines and/or ERW, 28 countries and five areas had adequate MRE programs in place, five more countries than in 2005.

Adequacy of MRE in 99 Countries and Eight Areas

|

No change: MRE adequate in 2005 and 2006-2007 |

MRE improved in 2006-2007 |

Added in 2006-2007 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

States Parties |

Afghanistan |

Guinea-Bissau |

Chile |

Cyprus |

|

Angola |

Nicaragua |

Croatia |

Estonia |

|

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Senegal |

El Salvador |

Honduras |

|

|

Sudan |

Liberia |

Kenya |

||

|

Cambodia |

Thailand |

Mauritania |

FYR Macedonia |

|

|

Ecuador |

Yemen |

|||

|

Eritrea |

||||

|

States not Party |

Kyrgyzstan |

South Korea |

Armenia |

|

|

Lebanon |

Sri Lanka |

Israel |

||

|

Areas |

Chechnya |

Somaliland |

Nagorno- Karabakh |

Taiwan |

|

Kosovo |

||||

“Inadequate” means that the MRE approach was too basic (for example, limited to lectures and without school-based MRE where this would be appropriate) or that the scale and geographical coverage of activities were too limited. Inadequate MRE was recorded in 34 countries in 2006-2007 (three less than in 2005) and in two areas (one less than in 2005).

|

No change: MRE inadequate in 2005 and 2006-2007 |

MRE decreased in 2006-2007 |

Added in 2006-2007 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

States Parties |

Albania |

Latvia |

Guatemala |

Serbia |

|

Belarus |

Mozambique |

Tajikistan |

||

|

Burundi |

Peru |

Uganda |

||

|

Chad |

Philippines |

|||

|

Colombia |

Rwanda |

|||

|

DR Congo |

Turkey |

|||

|

Ethiopia |

Ukraine |

|||

|

Iraq |

Zambia |

|||

|

Jordan |

Zimbabwe |

|||

|

States not Party |

Myanmar/Burma |

Laos |

Azerbaijan |

Morocco |

|

China |

Somalia |

Nepal |

||

|

India |

Syria |

Pakistan |

||

|

Iran |

Vietnam |

|||

|

Areas |

Palestine |

Western Sahara |

||

In the view of Landmine Monitor, new or additional MRE programs and activities are most needed in 13 countries, six are States Parties and seven states not party to the treaty. Programs urged for last year were due to begin in the second half of 2007 in Albania’s ERW-affected “hotspots,” in Algeria and in Egypt.

|

States Parties |

Colombia, Kuwait, Mozambique, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine |

|---|---|

|

States not Party |

Myanmar/Burma, Georgia, India, Laos, Nepal, Pakistan, Somalia |

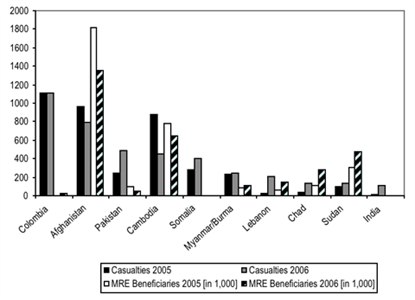

Whilst there may not be a simple causal relationship between MRE and incidence of casualties, comparison of casualty trends and MRE provision can identify countries for further analysis of the need for MRE. Where casualties are high, there is likely a need for more and better MRE (as well as other measures such as fencing, marking and clearance of mine/ERW-affected areas).

MRE Beneficiaries in 10 Countries with Most Casualties in 2005 and 2006

Non-State Armed Groups

Non-state armed groups (NSAGs) and related organizations provided limited MRE in three of the 10 countries with the most casualties in 2006: Myanmar/Burma, Somalia and Sri Lanka.

In Burma in 2006 the Karen National Union Department of Health and Welfare and the Committee Serving Internally Displaced Karen People started an MRE program and surveys of dangerous areas and mine casualties in rebel-controlled and contested sections of Karen state.[13]

In Sri Lanka the LTTE-linked organization White Pigeon conducted MRE in 75 mine/ERW-affected communities in eight divisions of Jaffna.

UN agencies and international and local NGOs provided MRE to populations living in areas accessed or controlled by NSAGs in Senegal, Colombia, Myanmar/Burma, Afghanistan, Somalia, Lebanon, Chad and Sudan in 2006-2007.

Evaluations and Studies

Several evaluations and studies of MRE in this reporting period provided more detailed information on the relationship between MRE and the incidence of mine/ERW casualties.

Cambodia noted a dramatic drop to 450 casualties in 2006, from an annual average of 846 each year since 2000. A study aiming to understand the causes found notable MRE improvements in targeting more at-risk people (particularly scrap metal dealers) and involvement of stakeholders such as the police. In addition, other factors including improved living conditions and access to arable land as well as stricter regulation of the scrap metal trade, were major contributors to the reduction in casualties. The study recommended even greater focus on people working in scrap metal yards and other high-risk and marginalized groups.[14]

In Laos two village case studies showed that while community MRE teams had increased people’s awareness of the danger of UXO this had not translated adequately into behavioral change.[15] Another assessment found that MRE in Laos had targeted unintentional risk-taking by the general public and had not sufficiently addressed the most at-risk groups and intentional risk-taking. It recommended engaging stakeholders and revising MRE messages and strategies to reach children and young people, scrap metal collectors, people who dismantle UXO and farmers.[16]

In Yemen a study found an unmet need for “greater involvement of women and girls in MRE and awareness campaigns by recruiting more women’s awareness teams and by extending the house-to-house approach.”[17]

In Colombia a survey of 378 people in three departments found low levels of understanding of mine/ERW threat and some dangerous practices, as well as some benefits from the limited MRE conducted.

In Somaliland a survey of 240 people found that while the number of people who had actually seen mines and ERW had significantly increased since a similar survey in 2002, knowledge of mines and safe behavior was not high and in some cases had even decreased. Eleven percent (five percent in 2002) did not know whether they lived in a mine/ERW-affected area.[18]

In 2006-2007 MRE evaluations, surveys and other studies were conducted in Armenia, Burma, Burundi, Cambodia, Colombia, Iraq, Jordan, Laos, Mauritania, Nepal, Pakistan, Syria, Tajikistan, Yemen and Somaliland.[19]

Emergency MRE

Emergency MRE refers to activities not only during or immediately after a conflict from which mine/ERW contamination results, but also to natural disasters such as flooding which may uncover and move mines, and to accidents such as the explosion of arms depots. In 2006 there were emergency MRE campaigns in several countries, notably in Lebanon, Mozambique and Nepal.[20]

In Lebanon immediately after the 14 August 2006 cease-fire ending the 34-day war with Israel an “urgent appeal” on the dangers of UXO to civilians was issued by UN agencies; warnings about approaching “suspicious objects” were also issued by the Lebanese army and Hezbollah. The Mine Action Coordination Center South Lebanon disseminated threat information, provided safety briefings and included community liaison as part of demining/EOD and data gathering. In October-November all affected areas in South Lebanon, some 150 villages, received MRE from four national NGOs; 135,000 children received MRE. The high level of MRE activities were maintained in the following months, including training new MRE volunteers. The focus as well as the scale of MRE changed to educate people about the new type of threat from submunitions scattered in habitable areas, in contrast to the previous threat (mostly from antipersonnel mines in known areas) with which people were familiar. Despite these efforts, and rapid clearance/EOD operations, there were over 200 mine/ERW casualties from August 2006 to May 2007—almost half of all casualties recorded in Lebanon since May 2000.

In Nepal, despite the April 2006 cease-fire, civilians continued to be killed and maimed by explosives abandoned or insecurely stored, and less often by antipersonnel mines.[21] An emergency campaign using mass media and 120 newly trained MRE activists was launched; in locations where incidents occurred communities were immediately targeted for emergency MRE.

Mozambique experienced heavy flooding in February 2007 in mined areas of Zambezia and Sofala provinces; emergency MRE was provided to 49,100 people in these areas. In addition, explosions in an arms depot in the capital Maputo on 22 March 2007 scattered UXO in a 10 kilometer radius affecting 14 neighborhoods; 103 civilians and 27 military personnel were killed and some 515 people were injured in the immediate aftermath. Emergency MRE was provided, reaching most of the 300,000 inhabitants. Nevertheless, some casualties from the incident continued; in June two children were killed and one seriously injured when they lit a fire on debris in which ERW from the depot explosion was buried; four soldiers were killed and 11 injured by UXO exploding as it was transported out of the area.

Conclusions

From its research for country reports in 2006-2007 Landmine Monitor concludes that both the amount of MRE has increased and its quality has improved overall. In many countries MRE is seen as an important contribution to lower casualty rates. However, campaign-style MRE that mainly focuses on children has proved to be insufficient. To achieve behavior change MRE should be community-based, with trained “focal points” and educators within affected communities receiving continued support. It has also become evident that MRE loses credibility if it is not accompanied by fencing and marking of dangerous areas and if it is not followed quickly by demining or explosive ordnance disposal to remove the actual threat. While some countries have made much progress in integrated MRE based on strong community links, with the support from the international mine action community, there remain mine/ERW-affected countries (including some States Parties) with high numbers of casualties but inadequate MRE programs.

[1] International Mine Action Standards 04.10, “Glossary of mine action terms, definitions and abbreviations,” Second Edition, 1 January 2003, www.mineactionstandards.org, accessed 30 August 2007.

[2] Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), “A Guide to Mine Action and Explosive Remnants of War,” Chapter 7, Mine Risk Education, Geneva, April 2007, p. 111.

[3] Six countries were dropped from this year’s list because no MRE activities were reported: Côte d’Ivoire, Georgia, Namibia, Poland, Russia (Chechnya is reported separately) and Tunisia; nine were added due to new activities: Cyprus, Estonia, Honduras, Kenya, Latvia, Libya, FYR Macedonia, Morocco and Serbia.

[4] Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, Cambodia, Chad, Chile, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus, DR Congo, Ecuador, Estonia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Guinea-Bissau, Honduras, Iraq, Jordan, Kenya, Latvia, Liberia, FYR Macedonia, Mauritania, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Peru, the Philippines, Rwanda, Senegal, Serbia, Sudan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, Yemen, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

[5] Armenia, Azerbaijan, Myanmar/Burma, China, India, Iran, Israel, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, Somalia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Syria and Vietnam.

[6] The areas are Chechnya, Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh, Palestine, Somaliland, Taiwan and Western Sahara.

[7] Landmine Monitor recorded 6.25 million MRE beneficiaries in 2004, 8.4 million in 2003 and 4.8 million in 2002.

[8] Sudan and Vietnam are additions to the top five. In 2005 Angola and Thailand were ranked in the top five; data recording in Angola was incomplete in 2006; Thailand noted that it had reported inflated numbers due to multiple registries in recent years.

[9] States Parties without MRE were: Algeria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cook Islands, Côte d’Ivoire, Denmark, Djibouti, France (Djibouti), Greece, Indonesia, Kuwait, Lithuania, Malawi, Moldova, Montenegro, Namibia, Niger, Panama, Republic of Congo, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Swaziland, Tunisia, United Kingdom (Falklands), Vanuatu and Venezuela. States not party to the treaty without MRE were: Cuba, Egypt, Georgia, North Korea, Mongolia, Oman, Poland, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Uzbekistan. In addition, no MRE activities were recorded in Abkhazia.

[10] States Parties’ Articles 7 reports including MRE in 2006 were: Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chad, Chile, Colombia, DR Congo, Croatia, Cyprus, Ecuador, Estonia, Eritrea, Greece, Honduras, Jordan, Mauritania, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Peru, Philippines, Senegal, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Yemen, Zambia and Zimbabwe. France reported on MRE but not regarding its mine-affected territory in Djibouti.

[11] States Parties: Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus, DR Congo, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Honduras, Iraq, Liberia, FYR Macedonia, Mauritania, Mozambique, Philippines, Rwanda, Senegal, Serbia, Sudan, Thailand, Uganda and Zambia; states not party: Armenia, Burma/Myanmar, Laos, Libya, Morocco, Nepal, Somalia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.

[12] In the case of Libya the available information was inadequate, and from one source only, to allow a reasonable judgment.

[13] The Karen National Union’s armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army, is likely the most prolific user of landmines among Myanmar/Burma’s many non-state armed groups. See report on Burma in this edition of Landmine Monitor.

[14] Ruth Bottomley, “A Study on the Dramatic Decrease of Mine/UXO Casualties in 2006 in Cambodia,” February 2007.

[15] “Local perspectives on living with UXO – A study of two Lao villages,” in GICHD, “Lao PDR Risk Management and Mitigation Model,” Geneva, February 2007, Annex B, pp. 47-78.

[16] Mines Advisory Group/Laos Youth Union, “UXO Risk Education Needs Assessment,” UNICEF, Vientiane, October 2006, pp. 8-11.

[17] B. Pound et al., “Departure of the Devil: Landmines and Livelihoods in Yemen,” Volume I, Main Report, GICHD, Geneva, 2006, p. 86.

[18] Handicap International (HI), “Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices related to Landmines and Unexploded Ordnance, North West Zone Somalia,” Summary, Lyon, January 2007, www.handicap-international.fr, accessed 15 July 2007.

[19] See country reports in this edition of Landmine Monitor. For Armenia, see Landmine Monitor Report 2006, p. 838.

[20] Emergency MRE and new MRE programs in response to new threats were also conducted in Chad, Colombia, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal and Sri Lanka in this reporting period.

[21] Informal Sector Service Center (INSEC), “Explosive Remnants of War and Landmines in Nepal: Understanding the Threat,” Kathmandu, December 2006.